Cosmology, Astrology, and Magic: Discourse, Schemes, Power, and Literacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional Sections Contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional sections contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D. Ph.D. Introduction Nichole Yalsovac Prophetic revelation, or Divination, dates back to the earliest known times of human existence. The oldest of all Chinese texts, the I Ching, is a divination system older than recorded history. James Legge says in his translation of I Ching: Book Of Changes (1996), “The desire to seek answers and to predict the future is as old as civilization itself.” Mankind has always had a desire to know what the future holds. Evidence shows that methods of divination, also known as fortune telling, were used by the ancient Egyptians, Chinese, Babylonians and the Sumerians (who resided in what is now Iraq) as early as six‐thousand years ago. Divination was originally a device of royalty and has often been an essential part of religion and medicine. Significant leaders and royalty often employed priests, doctors, soothsayers and astrologers as advisers and consultants on what the future held. Every civilization has held a belief in at least some type of divination. The point of divination in the ancient world was to ascertain the will of the gods. In fact, divination is so called because it is assumed to be a gift of the divine, a gift from the gods. This gift of obtaining knowledge of the unknown uses a wide range of tools and an enormous variety of techniques, as we will see in this course. No matter which method is used, the most imperative aspect is the interpretation and presentation of what is seen. -

The Cultural Evolution of Epistemic Practices: the Case of Divination Author: Ze Hong A1, Joseph Henricha

Title: The cultural evolution of epistemic practices: the case of divination Author: Ze Hong a1, Joseph Henricha Author Affiliations: a Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, 11 Divinity Avenue, 02138, Cambridge, MA, United States Keywords: cultural Evolution; divination; information transmission; Bayesian reasoning 1 To whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected] 1 ABSTRACT While a substantial literature in anthropology and comparative religion explores divination across diverse societies and back into history, little research has integrated the older ethnographic and historical work with recent insights on human learning, cultural transmission and cognitive science. Here we present evidence showing that divination practices are often best viewed as an epistemic technology, and formally model the scenarios under which individuals may over-estimate the efficacy of divination that contribute to its cultural omnipresence and historical persistence. We found that strong prior belief, under-reporting of negative evidence, and mis-inferring belief from behavior can all contribute to biased and inaccurate beliefs about the effectiveness of epistemic technologies. We finally suggest how scientific epistemology, as it emerged in the Western societies over the last few centuries, has influenced the importance and cultural centrality of divination practices. 2 1. INTRODUCTION The ethnographic and historical record suggests that most, and potentially all, human societies have developed techniques, processes or technologies that reveal otherwise hidden or obscure information, often about unknown causes or future events. In historical and contemporary small-scale societies around the globe, divination—"the foretelling of future events or discovery of what is hidden or obscure by supernatural or magical means” –has been extremely common, possibly even universal (Flad 2008; Boyer 2020). -

Complete Book of Necromancers by Steve Kurtz

2151 ® ¥DUNGEON MASTER® Rules Supplement Guide The Complete Book of Necromancers By Steve Kurtz ª Table of Contents Introduction Bodily Afflictions How to Use This Book Insanity and Madness Necromancy and the PC Unholy Compulsions What You Will Need Paid In Full Chapter 1: Necromancers Chapter 4: The Dark Art The Standard Necromancer Spell Selection for the Wizard Ability Scores Criminal or Black Necromancy Race Gray or Neutral Necromancy Experience Level Advancement Benign or White Necromancy Spells New Wizard Spells Spell Restrictions 1st-Level Spells Magic Item Restrictions 2nd-Level Spells Proficiencies 3rd-Level Spells New Necromancer Wizard Kits 4th-Level Spells Archetypal Necromancer 5th-Level Spells Anatomist 6th-Level Spells Deathslayer 7th-Level Spells Philosopher 8th-Level Spells Undead Master 9th-Level Spells Other Necromancer Kits Chapter 5: Death Priests Witch Necromantic Priesthoods Ghul Lord The God of the Dead New Nonweapon Proficiencies The Goddess of Murder Anatomy The God of Pestilence Necrology The God of Suffering Netherworld Knowledge The Lord of Undead Spirit Lore Other Priestly Resources Venom Handling Chapter 6: The Priest Sphere Chapter 2: Dark Gifts New Priest Spells Dual-Classed Characters 1st-Level Spells Fighter/Necromancer 2nd-Level Spells Thief / Necromancer 3rd-Level Spells Cleric/Necromancer 4th-Level Spells Psionicist/Necromancer 5th-Level Spells Wild Talents 6th-Level Spells Vile Pacts and Dark Gifts 7th-Level Spells Nonhuman Necromancers Chapter 7: Allies Humanoid Necromancers Apprentices Drow Necromancers -

J. Freedman Iban Augury In

J. Freedman Iban augury In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 117 (1961), no: 1, Leiden, 141-167 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 09:04:31AM via free access IBAN AUGURY* AN INTRODUCTORY COMPARISON n the second book of the Odyssey we are told of how Telemachus faced with the obduracy of the suitors who thronged his father's house called on Zeus to intervene, and how the all-seeing god, in answer to this prayer, sent forth two eagles from his mountain top: "Swift as the storm-blast they flew, wing-tip to wing in lordly sweep of pinions, until they were over the midmost of the many- tongued assembly. There they wheeled in full flight, with quiver- ing, outstretched, strong wings, and glazed down with fatal eyes upon the upturned faces. Next they ripped with tearing claws, each at the other's head and neck, swooping quickly to the right over the houses of the citizens. So long as eye could follow them everyone stood wondering at the birds and musing what future history this sign from heaven could mean." 1 Halitherses, "an elder of great standing who surpassed all his gener- ation in the science of bird-reading," saw in this event a portending of the return of Odysseus "carrying with him the seeds of bloody doom for every suitor". But the idle suitors would not listen and stayed on to meet their fate. This incident from the Odyssey illustrates the main doctrine of augury as it existed among the ancient Greeks. -

CSCP Support Materials for Eduqas GCSE Latin Component 2 Latin Literature and Sources (Themes) Superstition and Magic for Exami

CSCP Support Materials for Eduqas GCSE Latin Component 2 Latin Literature and Sources (Themes) Superstition and Magic For examination in 2021-2023 Source Images © University of Cambridge School Classics Project, 2019 PUBLISHED BY THE CAMBRIDGE SCHOOL CLASSICS PROJECT Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, 184 Hills Road, Cambridge, CB2 8PQ, UK http://www.CambridgeSCP.com © University of Cambridge School Classics Project, 2019 Copyright In the case of this publication, the CSCP is waiving normal copyright provisions in that copies of this material may be made free of charge and without specific permission so long as they are for educational or personal use within the school or institution which downloads the publication. All other forms of copying (for example, for inclusion in another publication) are subject to specific permission from the Project. First published 2019 version date: 20/12/2019 This document refers to the official examination images and texts for the Eduqas Latin GCSE (2021 - 2023). It should be used in conjunction with the information, images and texts provided by Eduqas on their website: Eduqas Latin GCSE (2021-2023) Information about several of the pictures in this booklet, together with useful additional material for the Theme, may be found in the support available online for Cambridge Latin Course, Book I, Stage 7 and Book III, Stages 22-23. © University of Cambridge School Classics Project, 2019 Picture 1: road surrounded by tombs This picture shows the tombs lining the road out of Pompeii towards Herculaneum. These marble tombs were in a prestigious location, as this was also the main route to and from Rome itself, and they commemorate important citizens and families who played an active role in the life of the town. -

Introduction to Anthropology

Introduction to Anthropology ANTH 101 ProfESSOR Kurt Reymers O. Religion, Magic and Witchcraft 1. Religion and Magic a. Religion, magic and/or witchcraft are cultural universals • All cultures have ideas about the supernatural. • All cultures have patterned rituals to help people get through life. O. Religion, Magic and Witchcraft b. Belief Systems can be typified as: Rational = Instrumental and Materialistic Supernatural = Faith-Based and Idealistic Most belief systems are a combination of the two. i. Science is instrumental and based on a rational understanding of nature. ii. Magic is also instrumental, but based on supernatural powers invoked through words or acts (coercive spells and rituals). iii. Religious experience is based purely on faith in a supernatural being or beings. ‹#› O. Religion, Magic and Witchcraft c. World Religions: In order of number of followers, they are: Christianity: 2.1 billion Islam: 1.3 billion Secular/Nonreligious/ Agnostic/Atheist: 1.1 billion Hinduism: 900 million Confucianism: 394 million Buddhism: 376 million Others… O. Religion, Magic and Witchcraft d. Anxiety Theory of Religion (Clifford Geertz) Religion is a result of the necessity of human beings to moderate the unpredictability of harsh and unforgiving social and environmental conditions. Example: Deities of fire Example: Mountains of God - Oldoinyo Lengai (Masai, Tanzania) O. Religion, Magic and Witchcraft 2. Sacred Beings and Divine Power a. Animatism: supernatural powers do not inhabit animals, plants or objects, but are beyond nature. Common in complex societies. ex: belief in heaven or hell. vs. Animism (nature religion) attributes to all of nature, animate and inanimate vital spiritual powers (animals, plants, rocks or clouds). -

Augury”? Find 26 Synonyms and 30 Related Words for “Augury” in This Overview

Need another word that means the same as “augury”? Find 26 synonyms and 30 related words for “augury” in this overview. Table Of Contents: Augury as a Noun Definitions of "Augury" as a noun Synonyms of "Augury" as a noun (26 Words) Usage Examples of "Augury" as a noun Associations of "Augury" (30 Words) The synonyms of “Augury” are: foretoken, preindication, sign, omen, indication, presage, warning, forewarning, harbinger, signal, promise, threat, menace, ill omen, forecast, prediction, prognostication, prophecy, straw in the wind, writing on the wall, hint, auspice, fortune telling, divining, forecasting the future, soothsaying Augury as a Noun Definitions of "Augury" as a noun According to the Oxford Dictionary of English, “augury” as a noun can have the following definitions: The interpretation of omens. An event that is experienced as indicating important things to come. A sign of what will happen in the future; an omen. Synonyms of "Augury" as a noun (26 Words) auspice A divine or prophetic token. divining Terms referring to the Judeo-Christian God. GrammarTOP.com A calculation or estimate of future events, especially coming forecast weather or a financial trend. forecasting the future A statement made about the future. An event that is experienced as indicating important things to foretoken come. A foretoken of problems that lay ahead. An advance warning. forewarning Officials had no forewarning of the attacks. An unknown and unpredictable phenomenon that causes an fortune telling event to result one way rather than another. A forerunner of something. harbinger Witch hazels are the harbingers of spring. A slight or indirect indication or suggestion. -

Ancient Divination and Experience OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 11/9/2019, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 11/9/2019, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 11/9/2019, SPi Ancient Divination and Experience OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 11/9/2019, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 11/9/2019, SPi Ancient Divination and Experience Edited by LINDSAY G. DRIEDIGER-MURPHY AND ESTHER EIDINOW 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Oxford University Press 2019 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2019 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of this licence should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2019934009 ISBN 978–0–19–884454–9 DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198844549.001.0001 Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

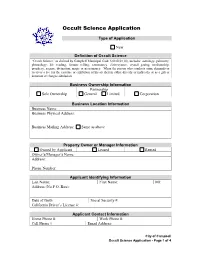

Occult Science Application

Occult Science Application Type of Application New Definition of Occult Science “Occult Science” as defined by Campbell Municipal Code 5.08.010 (10), includes astrology, palmistry, phrenology, life reading, fortune telling, cartomancy, clairvoyance, crystal gazing, mediumship, prophecy, augury, divination, magic or necromancy. When the person who conducts same demands or receives a fee for the exercise or exhibition of his art therein either directly or indirectly or as a gift or donation or charges admission. Business Ownership Information Partnership Sole Ownership General Limited Corporation Business Location Information Business Name: Business Physical Address: Business Mailing Address: Same as above Property Owner or Manager Information Owned by Applicant Leased Rented Owner’s/Manager’s Name: Address: Phone Number: Applicant Identifying Information Last Name: First Name: MI: Address (No P.O. Box): Date of Birth: Social Security #: California Driver’s License #: Applicant Contact Information Home Phone #: Work Phone #: Cell Phone # Email Address: City of Campbell Occult Science Application - Page 1 of 4 Applicant’s Residence History – Past Five Years Current: From (month/year): To (month/year): Previous: From (month/year): To (month/year): Previous: From (month/year): To (month/year): Previous: From (month/year): To (month/year): Applicant’s Employment History – Past Five Years Current: From (month/year): To (month/year): Previous: From (month/year): To (month/year): Previous: From (month/year): To (month/year): Previous: From (month/year): -

Flamen Augur

Augury Spells Wizard Level Spells Flamen Augur 3rd augury 5th clairvoyance Flamen Augurs are soothsayers and seers who use flames 7th divination and incense to foretell the future and the will of 9th commune supernatural forces. Augurs are skilled in Fire and Divination magic. Reader of Signs "eginning at (th level, when you cast a Divination spell Their skills are considerable and they guide emperors and using a spell slot of 2nd level or higher, you immediately generals alike, but they are rarely trusted. regain one use of 4ign of Flames. Bonus Cantrip Sign of Flames (Two Uses) When you select this school at 2nd level, you gain the "eginning at (th level, you can use 4ign of Flames twice guidance cantrip, if you don!t know it already. before a long rest, but only once on the same turn. Sign of Flames Magister Ignis "eginning at 2nd level, after you roll damage for a spell "eginning at )*th level, during your turn you can e$pend that deals #re damage, you can choose to draw on your two uses of 4ign of Flames. 2f you do so, all spells you cast e$tensive e$perience with flames to enhance your spell. until the end of your turn ignore resistance to #re damage %ou may immediately re-roll any number of damage dice and treat immunity to #re damage as resistance to #re and must use the new result, even if it is worse. damage instead. 'nce you use this feature, you must #nish a long rest before you can use it again. -

![Cicero Talks About the Tripudium]: There Might Be an Auspice If the Bird Were Free to Show Itself Outside Its Cage](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1040/cicero-talks-about-the-tripudium-there-might-be-an-auspice-if-the-bird-were-free-to-show-itself-outside-its-cage-3471040.webp)

Cicero Talks About the Tripudium]: There Might Be an Auspice If the Bird Were Free to Show Itself Outside Its Cage

Religion: public display & private worship Auspices, augury and interpretation Romans Romans in f cus The Romans deciphered the will of the Gods by reading the flights of birds. Auspices showed Romans what they were meant to do, or not to do; giving no explanation for the decision made except that it was the will of the gods. An augur would read the auspices before any public decision was made. Augurs had a huge amount of power. If they read that the auspices were unfavourable laws wouldn't be passed, assemblies wouldn't be gathered, and armies wouldn't go to war. The problem was that the auspices could be very easily manipulated and there are many anecdotes of augurs misreading the auspices to give the answer that was wanted. ex avibus oscines (from the calls of birds) watching the songs and eating patterns of birds, often chickens, particularly on military expeditions: if the birds would not eat, it was a bad sign - if the birds ate so greedily that scraps would fall from their mouths, this was Above: the liver of Piacenza, an Etruscan life-size model of a sheep’s liver used for favourable. interpreting entrails for divination. ex quadrupedibus (from four-legged animals) signs from animals being found in The most important auspices from: strange places or crossing a person’s path, ex caelo (from the sky) observing thunder and lightning, particularly Abnormal events like strangely timed taken to come from Jupiter. sneezing or stumbling could be considered ex avibus alites (from the birds in omens too. All omens had to be interpreted flight) observing the flight of birds. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Divination and Decision

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Divination and Decision-Making: Ritual Techniques of Distributed Cognition in the Guatemalan Highlands A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology and Cognitive Science by John J. McGraw Committee in charge: Professor Steven Parish, Chair Professor David Jordan, Co-Chair Professor Paul Goldstein Professor Edwin Hutchins Professor Craig McKenzie 2016 Copyright John J. McGraw, 2016 All rights reserved. The dissertation of John J. McGraw is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ___________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________ Co-chair ___________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page …....……………………………………………………………… iii Table of Contents ………………….……………………………….…………….. iv List of Figures ….…………………………………………………….…….……. vii List of Tables …......……………………………………………………………… viii List of Maps ………………………………………………………….……….…. ix Acknowledgments …..………………………………………..………………….. x Vita .………………….………………………………….………..……………… xiii Abstract of the Dissertation ..……………………………………………………. xv Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION …….………………………………..................... 1 Theoretical Background …………….…………..….……………… 2 Distributed Cognition