Forgive Them Lord, for They Know Not What They Do, Undated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Full, Edited Transcript of Joe Morse's Oral History Interview, “Minnesota

1 Full, Edited Transcript of Joe Morse’s Oral History Interview, “Minnesota to Mississippi: Civil Rights Organizing, 1964-1966” Date of the Interview: March 5th, 2016 Interviewer and Principal Investigator: Dr. Amanda Nagel, History Department, Winona State University Interviewee: Joe Morse Research and support: Dr. Tomas Tolvaisas, History Department, Winona State University Transcriber: Hayley Johnston, Winona State University Please note: the actual visual and textual sources (77 in total, all in .pdf format, which are illustrations provided by Joe Morse), are located in a separate file (entitled “Sources”) on this CD disc. The number assigned to each source in the edited interview transcript, below, matches the number of a textual source, a visual source, or a source that contains both kinds of information, in that separate file. AN: It is March 5th, 2016. My name is Amanda Nagel. I am here with Joe Morse to talk with him about his time in the Civil Rights Movement. I have had the pleasure of being able to work with both Tomas Tolvaisas and John Campbell from the Winona State University History Department to compile questions to ask Joe. Amanda Nagel (AN): We’ll talk a little about your background first. Can you please state for the record your full name, date and location of your birth, where you grew up, size of your family, and your education? Joe Morse (JM): My name is Joe Morse. Full name is Joseph. I was born in Duluth, Minnesota, in 1943, in Saint Mary’s hospital, same hospital Bob Dylan was born in. AN: Really? JM: Yeah. -

The Attorney General's Ninth Annual Report to Congress Pursuant to The

THE ATTORNEY GENERAL'S NINTH ANNUAL REPORT TO CONGRESS PURSUANT TO THE EMMETT TILL UNSOLVED CIVIL RIGHTS CRIME ACT OF 2007 AND THIRD ANNUALREPORT TO CONGRESS PURSUANT TO THE EMMETT TILL UNSOLVEDCIVIL RIGHTS CRIMES REAUTHORIZATION ACT OF 2016 March 1, 2021 INTRODUCTION This is the ninth annual Report (Report) submitted to Congress pursuant to the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of2007 (Till Act or Act), 1 as well as the third Report submitted pursuant to the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Reauthorization Act of 2016 (Reauthorization Act). 2 This Report includes information about the Department of Justice's (Department) activities in the time period since the eighth Till Act Report, and second Reauthorization Report, which was dated June 2019. Section I of this Report summarizes the historical efforts of the Department to prosecute cases involving racial violence and describes the genesis of its Cold Case Int~~ative. It also provides an overview ofthe factual and legal challenges that federal prosecutors face in their "efforts to secure justice in unsolved Civil Rights-era homicides. Section II ofthe Report presents the progress made since the last Report. It includes a chart ofthe progress made on cases reported under the initial Till Act and under the Reauthorization Act. Section III of the Report provides a brief overview of the cases the Department has closed or referred for preliminary investigation since its last Report. Case closing memoranda written by Department attorneys are available on the Department's website: https://www.justice.gov/crt/civil-rights-division-emmett till-act-cold-ca e-clo ing-memoranda. -

Cold Case Initiative 1St Report to Congress

THE ATTORNEY GENERAL'S FIRST ANNUAL REPORT TO CONGRESS PURSUANT TO THE EMMETT TILL UNSOLVED CIVIL RIGHTS CRIME ACTOF 2007 APRIL 7,2009 This report is submitted pursuant to the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of 2007, regarding the activities ofthe Department ofJustice (DOJ or the Department) under the Act. This initial report covers activities predating the Act, which was signed into law on October 7,2008, and the six months since its enactment.! 1. THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE'S EFFORTS TO INVESTIGATE AND PROSECUTE UNSOLVED CIVIL RIGHTS ERA HOMICIDES A. Overview and Background The Department of Justice fully supports the goals ofthe Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of2007. For more than 50 years, the Department of Justice has been instrumental in bringing justice to some ofthe nation's horrific civil rights era crimes. These crimes occurred during a terrible time in our nation's history when some people viewed their fellow Americans as inferior, and as threats, based only on the color of their skin. The Department of Justice believes that racially motivated murders from the civil rights era constitute L some of the greatest blemishes upon our history. As such, the Department stands ready to lend our assistance, expertise, and resources to assist in the investigation and possible prosecution of these matters. Unfortunately, federal jurisdiction over these historic cases is limited. The Ex Post Facto Clause of the Constitution and federal statutory law have limited the Department's ability to prosecute most civil rights era cases at the federal level. For example, two ofthe most important federal statutes that can be used to prosecute racially motivated homicides, 18 U.S.C. -

News Article "Mississippi Horror: a Doctor's Report"

~lJfOPSY ON RIGHTS CRUSADER )ff. W~"t, Mississippi HorrOrrr:,;:, But I wos disappolnted, too, .r I hecause I wouldn't ha.\'e a chance now 1o do something th 1 that rnl~ht help find the mur· r? A Doctor's Report ' 1 derers of those kids, Good· l rich, when he came on the .,._ phone, resoh·ed my amblva· il BY DAY1D 8PAIX, :'.\I.D. I was as surprised by the post· unteer for the Medical Com· t lent feelings for me. fj C09Yright 19'4, The Layman's Pren midnight call as I would have mittee for Human Rights. Reprinttcl bY Permission "Get d0\\'11 here anyway. g . been if I looked out the win· "Dave, can. you get dov,n Take the late plane. There's y The phone rang about 1 :30 dow and saw my ailing out here, right away?" something tunny g o i n g on a .m. I had just gone to sleep, board motor running a.round "To Mississippi?" about this business. I think r after a restless hour In bed by itself in the bay. "Immediately. The autopsy we may be able to arrange conjugating tour days of utter • • • for you to examine the bodies t failure to get my outboard for those three kids Is sched· THE OPERATOR said Jack· uJed fo r tomorrow, and the later. It may all be a Wild J motor running, and I walked son, Miss., was call!ng. goose chase, but let's try." i half-asleep down the dark hall attorneys for :Mrs. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:_December 13, 2006_ I, James Michael Rhyne______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in: History It is entitled: Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Wayne K. Durrill_____________ _Christopher Phillips_________ _Wendy Kline__________________ _Linda Przybyszewski__________ Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 By James Michael Rhyne M.A., Western Carolina University, 1997 M-Div., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1989 B.A., Wake Forest University, 1982 Committee Chair: Professor Wayne K. Durrill Abstract Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region By James Michael Rhyne In the late antebellum period, changing economic and social realities fostered conflicts among Kentuckians as tension built over a number of issues, especially the future of slavery. Local clashes matured into widespread, violent confrontations during the Civil War, as an ugly guerrilla war raged through much of the state. Additionally, African Americans engaged in a wartime contest over the meaning of freedom. Nowhere were these interconnected conflicts more clearly evidenced than in the Bluegrass Region. Though Kentucky had never seceded, the Freedmen’s Bureau established a branch in the Commonwealth after the war. -

Mississippi Freedom Summer: Compromising Safety in the Midst of Conflict

Mississippi Freedom Summer: Compromising Safety in the Midst of Conflict Chu-Yin Weng and Joanna Chen Junior Division Group Documentary Process Paper Word Count: 494 This year, we started school by learning about the Civil Rights Movement in our social studies class. We were fascinated by the events that happened during this time of discrimination and segregation, and saddened by the violence and intimidation used by many to oppress African Americans and deny them their Constitutional rights. When we learned about the Mississippi Summer Project of 1964, we were inspired and shocked that there were many people who were willing to compromise their personal safety during this conflict in order to achieve political equality for African Americans in Mississippi. To learn more, we read the book, The Freedom Summer Murders, by Don Mitchell. The story of these volunteers remained with us, and when this year’s theme of “Conflict and Compromise” was introduced, we thought that the topic was a perfect match and a great opportunity for us to learn more. This is also a meaningful topic because of the current state of race relations in America. Though much progress has been made, events over the last few years, including a 2013 Supreme Court decision that could impact voting rights, show the nation still has a way to go toward achieving full racial equality. In addition to reading The Freedom Summer Murders, we used many databases and research tools provided by our school to gather more information. We also used various websites and documentaries, such as PBS American Experience, Library Of Congress, and Eyes on the Prize. -

To South Africans of Color Such As My Mother, Who Came of Age in The

To South Africans of color such as my mother, who came of age in the years after 1948, when the white minority government launched the so- cial experiment known as apartheid, the United States beckoned as a country of promise and opportunity, a faraway place relatively free of the racialized degradation South Africa had come to epitomize. Americans, especially black Americans, were glamorous and well off and lived in beau- tiful homes, my mother and many in her generation believed. Although they understood that whites ran most things in America, too, it was hard to conceive of a life as oppressive as that experienced by people of color under the strictures of South African baaskaap, or white domination. As she planned to leave, my mother believed that she was escaping a country on the verge of self-destruction, its trauma highlighted by events that were increasingly capturing the world’s attention. In 1966, thousands of people had been evicted from District Six, a multiracial area in central Cape Town, and dumped on the barren wastelands of the Cape Flats. In May 1966, anti-apartheid activist Bram Fischer was sentenced to life in prison for his work with the African National Congress (ANC) and its military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), and the South African Communist Party. A month later, U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy toured the country, speaking out against apartheid, meeting with ANC president-general Albert Luthuli, and criticizing the govern- ment in a historic speech at the University of Cape Town. In July 1966, the government banned nearly one thousand people under the Suppres- sion of Communism Act and the Riotous Assemblies Act. -

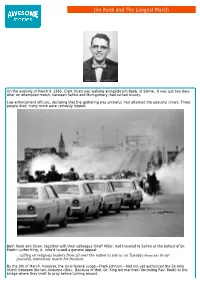

Jim Reeb and the Longest March

Jim Reeb and The Longest March On the evening of March 9, 1965, Clark Olsen was walking alongside Jim Reeb, in Selma. It was just two days after an attempted march, between Selma and Montgomery, had turned bloody. Law-enforcement officials, declaring that the gathering was unlawful, had attacked the peaceful crowd. Three people died; many more were seriously injured. Both Reeb and Olsen, together with their colleague Orloff Miller, had traveled to Selma at the behest of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who’d issued a general appeal: ...calling on religious leaders from all over the nation to join us on Tuesday [March 9th] in our peaceful, nonviolent march for freedom. By the 9th of March, however, the local federal judge—Frank Johnson—had not-yet authorized the 54-mile march between the two Alabama cities. Because of that, Dr. King led marchers (including Rev. Reeb) to the bridge where they knelt to pray before turning around. Later that night, Reeb decided to have dinner at Walkers Café (a local African-American restaurant) with Olsen and Miller. All three were Unitarian Universalist pastors. All three cared, a great deal, about social justice. They’d come to Selma to stand with other religious leaders and to march, in solidarity, with the people of Selma. As the three white pastors left the restaurant, they began to walk back to Brown Chapel AME Church (which was serving as the activists' headquarters in Selma). Reeb was still in town, despite his original plan to return home to Boston, because he wanted to stay one more day. -

Southern Sheriffs of the Twentieth Century

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2003 "Caretakers of the Color Line": Southern Sheriffs of the Twentieth Century Grace Earle Hill College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Criminology Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hill, Grace Earle, ""Caretakers of the Color Line": Southern Sheriffs of the Twentieth Century" (2003). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626415. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-st0q-g532 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “CARETAKERS OF THE COLOR LINE”: SOUTHERN SHERIFFS OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Grace E. Hill 2003 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts J Grace E. Hill Approved, June 2003 Judith Ewell Cindy Hahamo vitch Cam Walker TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract iv Introduction 2 Part I. Southern Sheriffs: Central Figures in Southern Racial History 8 Part II. Activism: Exposing and Challenging Southern Sheriffs’ Power 28 Part III. Sheriff Lawrence Rainey and Sheriff Jim Clark: 42 The Battle for Voting Rights in Mississippi and Alabama Part IV. -

Glittering Generalilties and Historic Myths, Brandeis School of Law

For further information contact: EMBARGOED until 7:30 p.m. (E.D.T.) Public Information Office (202) 479-3211 April 18, 2013 JUSTICE JOHN PAUL STEVENS (Ret.) UNIVERSITY OF LOUISVILLE BRANDEIS SCHOOL OF LAW 2013 Brandeis Medal Recipient The Seelbach Hilton Louisville, Kentucky April 18, 2013 Glittering Generalities and Historic Myths When I began the study of constitutional law at Northwestern in the fall of 1945, my professor was Nathaniel Nathanson, a former law clerk for Justice Brandeis. Because he asked us so many questions and rarely provided us with answers, we referred to the class as "Nat's mystery hour." I do, however, vividly remember his advice to "beware of glittering generalities." That advice was consistent with his former boss's approach to the adjudication of constitutional issues that he summarized in his separate opinion in Ashwander v. TVA, 297 U. S. 288, 346 (1936). In that opinion Justice Brandeis described several rules that the court had devised to avoid the unnecessary decision of constitutional questions. As I explained in the first portion of my long dissent in the Citizens United case three years ago, the application of the Brandeis approach to constitutional adjudication would have avoided the dramatic changes in the law produced by that decision. I remain persuaded that the case was wrongly decided and that it has done more harm than good. Today, however, instead of repeating arguments in my lengthy dissent, I shall briefly comment on the glittering generality announced in the per curiam opinion in Buckley v. Valeo in 1976 that has become the centerpiece of the Court's campaign finance jurisprudence, and then suggest that in addition to being skeptical about glittering generalities, we must also beware of historical myths. -

Mississippi: Is This America? (1962-1964) ROY WILKINS

Mississippi: Is This America? (1962-1964) ROY WILKINS: There is no state with a record that approaches that of Mississippi in inhumanity, murder and brutality and racial hatred. It is absolutely at the bottom of the list. NARRATOR: In 1964, the state of Mississippi called it an invasion. Civil rights workers called it Freedom Summer. To change Mississippi and the country, they would risk beatings, arrest, and their lives. FANNY CHANEY: You all know what my child is doing? He was trying for us all to make a better living. And he had two fellows from New York, had their own home and everything, didn't have nothing to worry, but they come here to help us. Did you all know they come here to help us? They died for us. UNITA BLACKWELL: People like myself, I was born on this river. And I love the land. It's the delta, and to me it's now a challenge, it's history, it's everything, to what black people it's all about. We came about slavery and this is where we acted it out, I suppose. All of the work, all them hard works and all that. But we put in our blood, sweat and tears and we love the land. This is Mississippi. WHITE HUNTER: I lived in this delta all my life, my parents before me, my grandparents. I've hunted and fished this land since I was a child. This land is composed of two different cultures, a white culture and a colored culture, and I lived close to them all my life. -

HS Social Studies Distance Learning Activities

HS Social Studies (Oklahoma History/Government) Distance Learning Activities TULSA PUBLIC SCHOOLS Dear families, These learning packets are filled with grade level activities to keep students engaged in learning at home. We are following the learning routines with language of instruction that students would be engaged in within the classroom setting. We have an amazing diverse language community with over 65 different languages represented across our students and families. If you need assistance in understanding the learning activities or instructions, we recommend using these phone and computer apps listed below. Google Translate • Free language translation app for Android and iPhone • Supports text translations in 103 languages and speech translation (or conversation translations) in 32 languages • Capable of doing camera translation in 38 languages and photo/image translations in 50 languages • Performs translations across apps Microsoft Translator • Free language translation app for iPhone and Android • Supports text translations in 64 languages and speech translation in 21 languages • Supports camera and image translation • Allows translation sharing between apps 3027 SOUTH NEW HAVEN AVENUE | TULSA, OKLAHOMA 74114 918.746.6800 | www.tulsaschools.org TULSA PUBLIC SCHOOLS Queridas familias: Estos paquetes de aprendizaje tienen actividades a nivel de grado para mantener a los estudiantes comprometidos con la educación en casa. Estamos siguiendo las rutinas de aprendizaje con las palabras que se utilizan en el salón de clases. Tenemos