Preparing to WIN a Guide for Successful Advocacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Used to Be Antifa Gabriel Nadales

I Used to be Antifa Gabriel Nadales There was a time in my life when I was angry, bitter, and deeply unhappy. I wanted to lash out at the whole “fascist” system—the greedy, heartless power structure that didn’t care about me or the rest of society’s innocent victims, a system that had robbed, beaten and stolen from my ancestors. The whole corrupt edifice deserved to be brought down, reduced to rubble. I was a perfect recruit for Antifa, the left-wing group which claims to fight against fascism. And so, I became a member. Now I was one of those who had the guts to fight against “the fascists” who were exploiting disadvantaged people. I wasn’t a ‘card-carrying’ antifascist—there is no such thing as an official Antifa membership. But I was ready at a moment’s notice to slip on the black mask and march in what Antifa calls “the black bloc”—a cadre of other black-clad Antifa members— to taunt police and destroy property. Antifa stands for “antifascist,” but that’s purposefully deceptive. For one thing, the very name is calibrated so that anyone who dares to criticize the group or its tactics can be labeled “fascist.” This allows Antifa to justify violence against all who dare stand up or speak out against them. A few groups boldly declare themselves Antifa, like “Rose City Antifa” in Portland. But most don’t, preferring to avoid the negative publicity. That’s part of Antifa’s appeal—and strength: It’s hard to pin down. -

Our 2020 Form

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) 2020 a Department of the Treasury Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Open to Public Internal Revenue Service a Go to www.irs.gov/Form990 for instructions and the latest information. Inspection A For the 2020 calendar year, or tax year beginning , 2020, and ending , 20 B Check if applicable: C Name of organization LEADERSHIP INSTITUTE D Employer identification number Address change Doing business as 51-0235174 Name change Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Initial return 1101 N HIGHLAND STREET (703) 247-2000 Final return/terminated City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code Amended return ARLINGTON, VA 22201 G Gross receipts $ 24,354,691 Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: MORTON BLACKWELL H(a) Is this a group return for subordinates? Yes ✔ No SAME AS C ABOVE H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( ) ` (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If “No,” attach a list. See instructions J Website: a WWW.LEADERSHIPINSTITUTE.ORG H(c) Group exemption number a K Form of organization: Corporation Trust Association Other a L Year of formation: 1979 M State of legal domicile: VA Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission or most significant activities: EDUCATE PEOPLE FOR SUCCESSFUL PARTICIPATION IN GOVERNMENT, POLITICS AND MEDIA. -

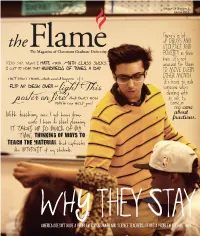

Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3

the Flame The Magazine of Claremont Graduate University Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3 The Flame is published by Claremont Graduate University 150 East Tenth Street Claremont, California 91711 ©2013 by Claremont Graduate BACK TO University Director of University Communications Esther Wiley Managing Editor Brendan Babish CAMPUS Art Director Shari Fournier-O’Leary News Editor Rod Leveque Online Editor WITHOUT Sheila Lefor Editorial Contributors Mandy Bennett Dean Gerstein Kelsey Kimmel Kevin Riel LEAVING Emily Schuck Rachel Tie Director of Alumni Services Monika Moore Distribution Manager HOME Mandy Bennett Every semester CGU holds scores of lectures, performances, and other events Photographers Marc Campos on our campus. Jonathan Gibby Carlos Puma On Claremont Graduate University’s YouTube channel you can view the full video of many William Vasta Tom Zasadzinski of our most notable speakers, events, and faculty members: www.youtube.com/cgunews. Illustration Below is just a small sample of our recent postings: Thomas James Claremont Graduate University, founded in 1925, focuses exclusively on graduate-level study. It is a member of the Claremont Colleges, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, distinguished professor of psychology in CGU’s School of a consortium of seven independent Behavioral and Organizational Sciences, talks about why one of the great challenges institutions. to positive psychology is to help keep material consumption within sustainable limits. President Deborah A. Freund Executive Vice President and Provost Jacob Adams Jack Scott, former chancellor of the California Community Colleges, and Senior Vice President for Finance Carl Cohn, member of the California Board of Education, discuss educational and Administration politics in California, with CGU Provost Jacob Adams moderating. -

INTERNSHIP RESOURCES and HELPFUL SEARCH LINKS These Sites Allow You to Do Advanced Searches for Internships Nationwide

CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE OFFICE OF CAREER & LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT 2017 INTERNSHIP LIST New Jobs…………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Politics/Non-profit…………………………………………………………………... 3 Public Policy/Non-profit …………………………………………………………... 5 Business……………………………………………………………………………... 10 Journalism and Media ……………………………………………………………… 11 Catholic/Pro-Life/Religious Freedom ……………………………………………… 13 Academic/Student Conferences and Fellowships ………………………………….. 14 Other ………………………………………………………………………………... 15 Internship Resources and Search Links …………………………………………….. 16 Please note: this is not meant to be exhaustive list, nor are all internships endorsed by Christendom College or the Office of Career Development. Many of the internships below are in the Metropolitan DC area, but there are thousands of internships available around the country. Use the resources on pg. 16 to do a search by field and location. Questions? Need help with your resume, cover letter, or composing an email? Contact Colleen Harmon: [email protected] ** Indicates alumni have or currently do work at this location. If you plan to apply to these internships, please let Colleen know so she can notify them. 1 NEW JOBS! National Journalism Center- summer deadline March 20 The National Journalism Center, a project of Young America's Foundation, provides aspiring conservative and libertarian journalists with the premier opportunity to learn the principles and practice of responsible reporting. The National Journalism Center combines 12 weeks of on-the- job training at a Washington, D.C.-based media outlet and once-weekly training seminars led by prominent journalists, policy experts, and NJC faculty. The program matches interns with print, broadcast, or online media outlets based on their interests and experience. Interns spend 30 hours/week gaining practical, hands-on journalism experience. Potential placements include The Washington Times, The Washington Examiner, CNN, Fox News Channel, and more. -

Vincent Russo Represents Clients on a Diverse Set of Legal and Public Policy Matters

Vincent Russo represents clients on a diverse set of legal and public policy matters. He was previously the Executive Counsel to Georgia Secretaries of State Brian Kemp and Karen Handel from 2008 to 2014, and served as the Assistant Commissioner of Securities in Georgia. Vincent currently serves as campaign counsel to Kemp for Governor and is Chief Deputy General Counsel to the Georgia Republican Party. Vincent has over a decade of legal, regulatory, and policy experience in Georgia, including in the areas of financial services, professional licensing, tax, real estate, elections, and procurement. He has worked on legislation involving the Georgia Civil Practice Act, the Georgia Business Corporations Code, the Georgia Election Code, the Georgia Uniform Securities Act, the Vincent Revised Georgia Trust Code, several professional licensing boards, and investment tax credits. In 2011 and 2012, Vincent oversaw and was Russo instrumental in the comprehensive overhaul of Georgia’s securities [email protected] regulations while serving as the Assistant Commissioner of Securities. Phone: 404-856-3260 Vincent brings a profound understanding of the pivotal relationship between government, business, and the law to his clients. As a litigator, Vincent represents clients in an array of business disputes, shareholder actions, real estate litigation, and administrative proceedings. He also advises clients bidding on government contracts, including representing them in procurement disputes. Because of his experience in both the public and private sector, Vincent is able to develop strategic plans to achieve his clients’ legislative, regulatory, and policy objectives at all levels of government, and provide direct advocacy with key government decision-makers on issues critical to his clients. -

Download File

Tow Center for Digital Journalism CONSERVATIVE A Tow/Knight Report NEWSWORK A Report on the Values and Practices of Online Journalists on the Right Anthony Nadler, A.J. Bauer, and Magda Konieczna Funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 7 Boundaries and Tensions Within the Online Conservative News Field 15 Training, Standards, and Practices 41 Columbia Journalism School Conservative Newswork 3 Executive Summary Through much of the 20th century, the U.S. news diet was dominated by journalism outlets that professed to operate according to principles of objectivity and nonpartisan balance. Today, news outlets that openly proclaim a political perspective — conservative, progressive, centrist, or otherwise — are more central to American life than at any time since the first journalism schools opened their doors. Conservative audiences, in particular, express far less trust in mainstream news media than do their liberal counterparts. These divides have contributed to concerns of a “post-truth” age and fanned fears that members of opposing parties no longer agree on basic facts, let alone how to report and interpret the news of the day in a credible fashion. Renewed popularity and commercial viability of openly partisan media in the United States can be traced back to the rise of conservative talk radio in the late 1980s, but the expansion of partisan news outlets has accelerated most rapidly online. This expansion has coincided with debates within many digital newsrooms. Should the ideals journalists adopted in the 20th century be preserved in a digital news landscape? Or must today’s news workers forge new relationships with their publics and find alternatives to traditional notions of journalistic objectivity, fairness, and balance? Despite the centrality of these questions to digital newsrooms, little research on “innovation in journalism” or the “future of news” has explicitly addressed how digital journalists and editors in partisan news organizations are rethinking norms. -

GORDON DAKOTA ARNOLD [email protected] EDUCATION

GORDON DAKOTA ARNOLD [email protected] EDUCATION Hillsdale College Hillsdale, MI Ph.D. in Politics Expected May 2023 Regent University Virginia Beach, VA B.A. in Government, Minor in History August 2013 to May 2017 FOREIGN LANGUAGES Latin Reading Competency TEACHING EXPERIENCE Regent University Academic Support Center Virginia Beach, VA Writing Tutor August 2016 to May 2017 May 2019 to June 2020 Tutored undergraduate and graduate students to better organize, stylize, and format academic writing projects by delineating linguistic rules for clarity, concision, grace, and grammar. RESEARCH EXPERIENCE Hillsdale College Hillsdale, MI Graduate Faculty Research Assistant August 2018 to May 2020 Assisted Hillsdale political scientists in their scholarship by transcribing lectures and editing drafts of their written scholarship. Hillsdale College Hillsdale, MI Library Archivist August 2020 to Present Assists the library in logging and transcribing information from the letters and essays of Harry V. Jaffa and other scholars affiliated with Hillsdale College. PUBLICATIONS Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles: “Truth is Never Out of Date”: The Political Thought of Robert Lewis Dabney,” Journal of Markets and Morality (In-Progress; Received Revise and Resubmit). “Calvin Coolidge: Classical Statesman,” Humanitas Journal, Vol. XXXII, Nos. 1 and 2 (2019). Book Reviews: “It’s a Perfect Time to Rediscover the Virtues of Andrew Jackson,” The Federalist (January 25, 2019). http://www.thefederalist.com/2019/01/25/rediscovering-the-virtues-of-andrew-jackson/ Online Journal Articles: “The Democratic Impulse of the Scholars in Friedrich Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil,” Voegelin View (Forthcoming; Confirmed for Publication Nov. 2020). “Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Immanuel Kant’s Competing Views of the Enlightenment,” Voegelin View (Forthcoming; Confirmed for Publication Dec. -

Educating Educators in the Age of Trump

ISSN: 1941-0832 Educating Educators in the Age of Trump by Erika Kitzmiller PHOTO COURTESY OF AUTHOR RADICAL TEACHER 65 http://radicalteacher.library.pitt.edu No. 111 (Summer 2018) DOI 10.5195/rt.2018.475 n January 11, 2018, the day that our president learned in this course into our own classrooms. I wanted uttered his reprehensible comments about Haiti to teach this course to give students an opportunity to O and Africa, I received an email from an explore the history of racism and white supremacy that investigative reporter affiliated with Campus Reform. was visibly on display during and after the 2016 Campus Reform is a conservative website under the presidential campaign so that they, a group comprised direction of the Leadership Institute, a non-profit founded primarily of white educators, could explore this history with in 1979 to teach “conservatives of all ages how to succeed their own students. This history is rarely, if ever covered in politics, government, and the media.”1 Campus Reform in schools, because most white educators do not know it. I has daily reports on what its authors claim to be incidents wanted to change that. of liberal bias, political indoctrination, and restrictions on free speech in American college classrooms.2 I was their new target. The reporter asked me to answer several I wanted to teach this course to questions about my upcoming course, “Education in the give students an opportunity to Age of Trump.” In his email, the reporter asked me if my explore the history of racism and course might “alienate students who may have supported white supremacy that was visibly the current U.S. -

The Long New Right and the World It Made Daniel Schlozman Johns

The Long New Right and the World It Made Daniel Schlozman Johns Hopkins University [email protected] Sam Rosenfeld Colgate University [email protected] Version of January 2019. Paper prepared for the American Political Science Association meetings. Boston, Massachusetts, August 31, 2018. We thank Dimitrios Halikias, Katy Li, and Noah Nardone for research assistance. Richard Richards, chairman of the Republican National Committee, sat, alone, at a table near the podium. It was a testy breakfast at the Capitol Hill Club on May 19, 1981. Avoiding Richards were a who’s who from the independent groups of the emergent New Right: Terry Dolan of the National Conservative Political Action Committee, Paul Weyrich of the Committee for the Survival of a Free Congress, the direct-mail impresario Richard Viguerie, Phyllis Schlafly of Eagle Forum and STOP ERA, Reed Larson of the National Right to Work Committee, Ed McAteer of Religious Roundtable, Tom Ellis of Jesse Helms’s Congressional Club, and the billionaire oilman and John Birch Society member Bunker Hunt. Richards, a conservative but tradition-minded political operative from Utah, had complained about the independent groups making mischieF where they were not wanted and usurping the traditional roles of the political party. They were, he told the New Rightists, like “loose cannonballs on the deck of a ship.” Nonsense, responded John Lofton, editor of the Viguerie-owned Conservative Digest. If he attacked those fighting hardest for Ronald Reagan and his tax cuts, it was Richards himself who was the loose cannonball.1 The episode itself soon blew over; no formal party leader would follow in Richards’s footsteps in taking independent groups to task. -

Target San Diego

Target San Diego The Right Wing Assault on Urban Democracy and Smart Government Lee Cokorinos Target San Diego The Right Wing Assault on Urban Democracy and Smart Government A Report for the Center on Policy Initiatives Lee Cokorinos November 2005 Table of Contents Acknowledgments . ii Foreword . iii Executive Summary . v Introduction: The National Significance of the Battle for San Diego . 1 1. The National Context: Key Organizations Leading the Right’s Assault on the States and Cities . 5 A. The American Legislative Exchange Council . 7 B. The State Policy Network . 13 C. The Claremont Institute for the Study of Statesmanship and Political Philosophy . 17 D. The Pacific Research Institute . 21 E. Americans for Tax Reform and the Project for California’s Future . 25 F. The Reason Foundation . 33 2. The Performance Institute and the Assault on San Diego . 39 3. The Battle for America’s Cities: A National Engagement . 49 Endnotes . 57 I ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Acknowledgments This report was made possible through the generous support of the New World Foundation. Special thanks go to Colin Greer and Ann Bastian of New World for their leadership in fostering the movement for progressive renewal. Thanks also to Donald Cohen of the Center on Policy Initiatives for contributing keen insights and the benefit of his ground level experience at engaging the right at every step of the research and writing, to Murtaza Baxamusa of CPI for sharing his expertise, and to veteran political researcher Jerry Sloan for his valuable advice. Jerry’s decades of research on the California and the national right have educated a generation of activists. -

“Fractures, Alliances, and Mobilizations: Emerging Analyses of the Tea Party Movement”

Tea Party Conference Proceedings 1 “Fractures, Alliances, and Mobilizations: Emerging Analyses of the Tea Party Movement” A Conference Sponsored by the Center for the Comparative Study of Right-Wing Movements Friday, October 22, 2010 Alumni House, University of California, Berkeley Conference Proceedings Prepared by Rebecca Alexander Welcome and Opening Remarks Lawrence Rosenthal opens the conference by describing the history of the Center for the Comparative Study of Right Wing Movements (CCSRWM) and the impetus behind a conference to study the Tea Party movement. The CCSRWM opened its doors in March of 2009. When work on the center first began, Rosenthal says, many people scoffed at the idea because, with Obama moving in and Bush and the Republicans moving out, they thought concerns about right- wing movements were over. When the Center opened, a couple of months into the Obama presidency, however, nobody was scoffing anymore. The right was louder than ever, becoming the political phenomenon of the year, coalescing into something we struggle today to understand. Rosenthal explains that The Tea Party movement is an extraordinary expression of an American Right that not only did not go away after Obama’s resounding electoral victory, but regrouped and moved further to the right, embracing ideas that American conservatives had rejected years ago and mobilizing a Perot-sized chunk of the electorate. Rosenthal says he is struck by similarities between 1993 and 2008, because in both cases the presidency of an elected Democrat was deemed illegitimate by much of the right. In the first case, right-wing objection to Bill Clinton resulted in impeachment; a phenomenon that Rosenthal suggests may repeat itself in the age of “Birthers” if Republicans win majorities in the House and Senate. -

Texas Students for Concealed Carry - Press Releases - Feb

Texas Students for Concealed Carry - Press Releases - Feb. 17 - Mar. 3, 2016 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE – 02/17/2016 SCC's Preliminary Response to Campus Carry Policies Approved by UT-Austin President Gregory Fenves AUSTIN, TX - Over the past two months, Students for Concealed Carry has repeatedly explained how two of the proposals of UT-Austin’s campus carry working group violate the intent of Texas’s new campus carry law and how one of those proposals greatly increases the odds that a license holder will suffer an accidental discharge on campus. Unfortunately, UT-Austin President Gregory Fenves chose to punt the issue to the courts rather than stand up to a cabal of fear-mongering professors. SCC is confident that the university’s gun-free-offices policy and empty-chamber policy will not stand up to legal scrutiny; therefore, our Texas chapter will now shift its focus to litigation. Simultaneously, we will continue to work with the governor’s office to explore the possibility of getting a clarification of the campus carry law added to Governor Abbott’s impending call for a special legislative session to address school finance. ### FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE – 02/23/2016 What other laws should public colleges be allowed to "opt out" of? AUSTIN, TX - Following the announcement that UT-Austin President Gregory Fenves will, in accordance with Texas Senate Bill 11, allow the licensed concealed carry of handguns in most university classrooms, numerous pundits and media outlets are once again calling for Texas legislators to allow public colleges to opt out of the state’s new “campus carry” law.