A Propaganda Model Case Study of ABC Primetime •Ÿnorth Korea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Democratic Detriment of Episodic Television News

Pikkert. Function after Form … The McMaster Journal of Communication Volume 4, Issue 1 2007 Article 6 Function after Form: The Democratic Detriment of Episodic Television News Owen Pikkert McMaster University Copyright © 2007 by the authors. The McMaster Journal of Communication is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). http://digitalcommons.mcmaster.ca/mjc The McMaster Journal of Communication. Volume 4 [2007], Issue 1, Article 6 Function after Form: The Democratic Detriment of Episodic Television News Owen Pikkert Abstract This paper analyzes the impact of television news upon political mobilization and awareness. In particular, it places a strong emphasis on the inherent inability of episodic news to form a cognitive framework through which to understand current events. The paper begins with preliminary statements on the significance of television news and describes the limits of the paper’s scope. It then examines the correlation of episodic television news with political cynicism, the trivialization of news content, and the formation of a pro-establishment attitude among viewers. A greater stress is placed upon the way in which television news is presented than upon news content or on the paucity of social capital. In conclusion, an argument is made for the imposition of sound bite quotas, with the desire to counter the handicaps of the episodic medium. KEYWORDS: Episodic, news, television, trivialization, political bias, pro- establishment, political cynicism, television medium, reporting, sound bite, post-structuralism The McMaster Journal of Communication. Volume 4 [2007], Issue 1, Article 6 The McMaster Journal of Communication 2007 Volume 4, Issue 1 Function after Form: The Democratic Detriment of Episodic Television News Owen Pikkert McMaster University Introduction elevision, as a channel for expression and public debate, is crucial to the health of a democratic state. -

“Authentic” News: Voices, Forms, and Strategies in Presenting Television News

International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 4239–4257 1932–8036/20160005 Doing “Authentic” News: Voices, Forms, and Strategies in Presenting Television News DEBING FENG1 Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, China Unlike print news that is static and mainly composed of written text, television news is dynamic and needs to be delivered with diversified presentational modes and forms. Drawing upon Bakhtin’s heteroglossia and Goffman’s production format of talk, this article examined the presentational forms and strategies deployed in BBC News at Ten and CCTV’s News Simulcast. It showed that the employment of different presentational elements and forms in the two programs reflects two contrasting types of news discourse. The discourse of BBC News tends to present different, and even confrontational, voices with diversified presentational forms, such as direct mode of address and “fresh talk,” thus likely to accentuate the authenticity of the news. The other type of discourse (i.e., CCTV News) seems to prefer monologic news presentation and prioritize studio-based, scripted news reading, such as on-camera address or voice- overs, and it thus creates a single authoritative voice that is likely to undermine the truth of the news. Keywords: authenticity, mode of address, presentational elements, voice, television news The discourse of television news has been widely studied within the linguistic world. Early in the 1970s, researchers in the field of critical linguistics (CL; e.g., Fowler, 1991; Fowler, Hodge, Kress, & Trew, 1979; Hodge & Kress, 1993) paid great attention to the ideological meaning of news by drawing upon a kit of linguistic tools such as modality, transitivity, and transformation. -

The #1 Secret for Improving Your Speaking Voice

The #1 Secret for Improving Your Speaking Voice (That Most Voice Coaches Don’t Know!) Nancy Daniels 2 The #1 Secret For Improving Your Speaking Voice (That Most Voice Coaches Don’t Know!) by Nancy Daniels, The Voice Lady www.voicedynamic.com [email protected] 888-627-2824 856-627-6040 ©2010 3 Just When You Think You Have Your Act Together …You Hear Yourself on Your Answering Machine! Do you believe that the image you project has an impact on your professional or business life? I would imagine that your answer is yes. I would also imagine that you have heard yourself on some type of recording equipment – your voicemail, an answering machine, a camcorder, or maybe even an old audio tape recorder. When you hear your recorded voice, what is your reaction? Are you shocked, maybe embarrassed? How about humiliated? In all the years I have been speaking professionally about the sound of the voice, I always ask that question of my audience. 99% do not raise their hands. In fact, most tend to look around the room uncomfortably, possibly hoping I will not call upon them to speak. The reason for their discomfort is because, in being asked that question, they have an idea of what I am going to say next and they do not want to hear it. It goes something like this: The voice you hear on your voicemail or other type of recording equipment is how everyone else recognizes you. Let 4 me say that again. The voice which embarrasses, humiliates, disgusts, or shocks you is how everyone else recognizes you. -

Video Tapes Boxes 116 - 134

Box Item Location Sub-series Description Video Tapes Series 13: Video Tapes Boxes 116 - 134 116 1 01-8-26- Senate Democratic Leadership Council Conference, Cleveland 08-06-0-1 - April 1981 - VHS. 2 KNBC-TV, Los Angeles - interview of John Glenn during his 1984 presidential campaign - November 27, 1983 - VHS. 3 John Glenn speech given at The Ohio State University during his 1984 presidential campaign - November 30, 1983 - VHS. 4 John Glenn speech on nuclear arms control at The Ohio State University during his 1984 presidential campaign - December 1983 - VHS. 5 "Believe in the Future Again" - 1984 presidential campaign video - circa 1983-1984 - VHS. 6 "Believe in the Future Again" - 1984 presidential campaign - circa 1983-1984 - VHS (copy 2). 7 "International Dateline" - panel discussions on U.S./Israeli relations with Senators John Glenn, Robert Dole, and Christopher Dodd, sponsored by the United Jewish Appeal - May 12 & 19, 1985 - VHS. 8 Statements by Senators Howard Metzenbaum and John Glenn taped for a Cable in the Classroom Workshop, sponsored by Cox Cable Systems - circa 1985 - VHS. 9 John Glenn’s taped statement to the National Technological University graduation ceremony - Cambridge, Ohio - November 19, 1986 – VHS 10 Give Kids the World Foundation promotional video narrated by Walter Cronkite, produced by Disney- MGM Studios - circa 1986 - VHS. 11 Public service announcement, International Aerospace Hall of Fame - June 12, 1987 -VHS. 12 Floor statement on the Persian Gulf - June 17, 1987; Democratic debate on "Firing Line" - July 1, 1987; and Trade Bill hearing - July 14, 1987 - VHS. 13 John Glenn’s floor statement on the Republican Campaign Committee’s strategy of portraying Howard Metzenbaum as a communist sympathizer - July 29, 1987 - VHS. -

Sound Bite Democracy

Sound Bite Democracy by Daniel C. Hallin tyranny of the sound stories and the role of the journalist in bite has been universally putting them together. Today,TV news is denounced as a leading much more "mediated"by journaliststhan cause of the low state of it was during the 1960s and early 70s. An- America's political dis- chors and reporterswho once played a rel- course. "Ifyou couldn't say atively passive role, frequently doing little it in less than 10 seconds," former gover- more than setting the scene for the candi- nor Michael Dukakis declared after the date or other newsmaker whose speech 1988 presidential campaign, "it wasn't would dominate the report, now more ac- heard because it wasn't aired." Somewhat tively "package"the news. This new style of chastened, the nation's television networks reporting is not so much a product of now are suggesting that they will be more journalistic hubris as the result of several generous in covering the 1992 campaign, converging forces- technological, politi- and some candidateshave alreadybeen al- cal, and economic- that have altered the lowed as much as a minute on the evening imperativesof TV news. news. However, a far more radical change To appreciatethe magnitude of this ex- would be needed to returneven to the kind traordinarychange, it helps to look at spe- of coverage that prevailed in 1968. cific examples. On October 8, 1968, Walter During the Nixon-Humphrey contest Cronkiteanchored a CBS story on the cam- that year, nearly one-quarterof all sound paigns of RichardNixon and Hubert Hum- bites were a minute or longer, and occa- phrey that had five sound bites averaging sionally a major political figure would 60 seconds. -

CMST 132 – Techniques & Technology of Propaganda Spring

CMST 132 – Techniques & Technology of Propaganda Spring 2019 INSTRUCTOR: Michael Korolenko PHONE: 425-564-4109 OFFICE HOURS: By Appointment TEXTBOOK: AMUSING OURSELVES TO DEATH, by Neil Postman COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course focuses on the technological and communicative techniques of film and video that allow information to be targeted at specific individuals and groups, to create opinions, generate sales, develop propaganda, and other goals of media persuasion. It is the goals to: 1) increase student awareness of media persuasion by examining a variety of historical and current media campaigns; 2) demonstrate the techniques and technologies of media-based persuasion; 3) give students the opportunity to test and validate persuasion techniques with simple media presentations; and 4) assist in the development of critical analysis skills as applied to the production of media messages. This will be accomplished through online "lectures", discussions, written assignments, and a variety of film and video clips. THE ONLINE COURSE will be presented in the form of a museum or World’s Fair exhibit dealing with the technology of persuasion and propaganda. Each area will contain different forms of propaganda: print, television, etc. as well as the types of propaganda and persuasion we face in our technological society: political, product-oriented, philosophically oriented, etc. COURSE LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of the class, the student will be able to: 1. define the terms: media, persuasion, propaganda, technology application, symbol, metaphor, "yellow journalism," editorial, sound bite, manipulation, soft sell, motivation, instructional training, education, hands-on, virtual reality, educational television, documentary film/video, docudrama, advertising, infomercial. 2. list and explain the significance of five or more historical examples of media persuasion and propaganda between 1600 and 1990. -

Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time

The Business of Getting “The Get”: Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung The Joan Shorenstein Center I PRESS POLITICS Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 IIPUBLIC POLICY Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government The Business of Getting “The Get” Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 INTRODUCTION In “The Business of Getting ‘The Get’,” TV to recover a sense of lost balance and integrity news veteran Connie Chung has given us a dra- that appears to trouble as many news profes- matic—and powerfully informative—insider’s sionals as it does, and, to judge by polls, the account of a driving, indeed sometimes defining, American news audience. force in modern television news: the celebrity One may agree or disagree with all or part interview. of her conclusion; what is not disputable is that The celebrity may be well established or Chung has provided us in this paper with a an overnight sensation; the distinction barely nuanced and provocatively insightful view into matters in the relentless hunger of a Nielsen- the world of journalism at the end of the 20th driven industry that many charge has too often century, and one of the main pressures which in recent years crossed over the line between drive it as a commercial medium, whether print “news” and “entertainment.” or broadcast. One may lament the world it Chung focuses her study on how, in early reveals; one may appreciate the frankness with 1997, retired Army Sergeant Major Brenda which it is portrayed; one may embrace or reject Hoster came to accuse the Army’s top enlisted the conclusions and recommendations Chung man, Sergeant Major Gene McKinney—and the has given us. -

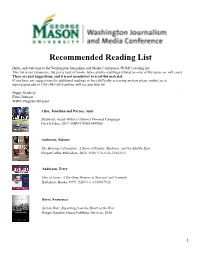

Recommended Reading List

Recommended Reading List Hello, and welcome to the Washington Journalism and Media Conference (WJMC) reading list. This list is not exhaustive, but just a taste of books, news articles and blogs related to some of the topics we will cover. These are just suggestions, and it is not mandatory to read this material. If you have any suggestions for additional readings or have difficulty accessing an item please contact us at [email protected] or (703) 993-5010 and we will see you July 16! Happy Reading! Elena Johnson WJMC Program Director Allen, Jonathan and Parnes, Amie Shattered: Inside Hillary Clinton's Doomed Campaign Deckle Edge, 2017. ISBN 9780553447088 Anderson, Sulome The Hostage’s Daughter: A Story of Family, Madness, and the Middle East HarperCollins Publishers, 2016. ISBN 978-0-06-238549-9. Anderson, Terry Den of Lions: A Startling Memoir of Survival and Triumph Ballantine Books, 1995. ISBN-10: 0345467928. Borri, Francesca Syrian Dust: Reporting from the Heart of the War. Pengin Random House Publisher Services, 2016. 1 Committee to Protect Journalists Attacks on the Press: The New Face of Censorship 1st Edition John Wiley & Sons, 2017. ISBN 978-1119361008 Dickerson, John Whistlestop: My Favorite Stories from Presidential Campaign History Hachette Book Group, 2016. ISBN 1455569453 Frantzich, Stephen E. Founding Father: How C-SPAN’s Brian Lamb Changed Politics in America. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008. ISBN-10: 074255809. Kovach, Bill & Rosenstiel, Tom The Elements of Journalism. Three Rivers Press, 2014, ISBN-0804136785. Lamb, Brian and CSPAN Sundays at Eight: 25 Years of Stories from CSPANS Q&A and Booknotes. -

Society Persuasion In

PERSUASION IN SOCIETY HERBERT W. SIMONS with JOANNE MORREALE and BRUCE GRONBECK Table of Contents List of Artwork in Persuasion in Society xiv About the Author xvii Acknowledgments xix Preface xx Part 1: Understanding Persuasion 1. The Study of Persuasion 3 Defining Persuasion 5 Why Is Persuasion Important? 10 Studying Persuasion 14 The Behavioral Approach: Social-Scientific Research on the Communication-Persuasion Matrix 15 The Critical Studies Approach: Case Studies and “Genre-alizations” 17 Summary 20 Questions and Projects for Further Study 21 2. The Psychology of Persuasion: Basic Principles 25 Beliefs and Values as Building Blocks of Attitudes 27 Persuasion by Degrees: Adapting to Different Audiences 29 Schemas: Attitudes as Knowledge Structures 32 From Attitudes to Actions: The Role of Subjective Norms 34 Elaboration Likelihood Model: Two Routes to Persuasion 34 Persuasion as a Learning Process 36 Persuasion as Information Processing 37 Persuasion and Incentives 38 Persuasion by Association 39 Persuasion as Psychological Unbalancing and Rebalancing 40 Summary 41 Questions and Projects for Further Study 42 3. Persuasion Broadly Considered 47 Two Levels of Communication: Content and Relational 49 Impression Management 51 Deception About Persuasive Intent 51 Deceptive Deception 52 Expression Games 54 Persuasion in the Guise of Objectivity 55 Accounting Statements and Cost-Benefit Analyses 55 News Reporting 56 Scientific Reporting 57 History Textbooks 58 Reported Discoveries of Social Problems 59 How Multiple Messages Shape Ideologies 59 The Making of McWorld 63 Summary 66 Questions and Projects for Further Study 68 Part 2: The Coactive Approach 4. Coactive Persuasion 73 Using Receiver-Oriented Approaches 74 Being Situation Sensitive 76 Combining Similarity and Credibility 79 Building on Acceptable Premises 82 Appearing Reasonable and Providing Psychological Income 85 Using Communication Resources 86 Summary 88 Questions and Projects for Further Study 89 5. -

Oprah Winfrey Network January 2011 Highlights

OWN: OPRAH WINFREY NETWORK JANUARY 2011 HIGHLIGHTS Visit press.discovery.com/own for select episodic photography and screeners. NEW SERIES “Anna and Kristina’s Grocery Bag” Series Premiere – Monday, January 3 at 3:00 p.m. ET/PT (30 minutes) We’ve all seen beautiful and delicious meals skillfully executed by professional chefs, but what happens when two average home cooks try to tackle the culinary arts? In the new series, “Anna and Kristina’s Grocery Bag,” hosts Anna Wallner and Kristina Matisic focus their efforts in the kitchen, putting popular cookbooks to the test. Each episode tackles one cookbook, with Anna and Kristina recreating the recipes as written and exploring how easy each dish is to prepare. Along the way, they offer entertaining and informative thoughts on ingredients, food-prep techniques and kitchen products. To judge the results, Anna and Kristina are joined by world-class chefs and food experts, who rate the meal and decide if the chosen cookbook delivers on its promises. Episodes air daily, Monday through Friday, at 3:00 p.m. ET/PT “Ask Oprah’s All Stars” Series Premiere - Sunday, January 2 at 8:00 p.m. ET/PT (120 minutes) For the first time, Oprah’s All Stars – Dr. Phil, Suze Orman, and Dr. Mehmet Oz – will appear on one stage to answer viewers’ pressing questions about health, wealth, and mental well- being. Shot before a live studio audience, this four-part special offers unprecedented access to Oprah Winfrey’s go-to group of masters as they share their wisdom and help viewers jumpstart their best year ever. -

Weller Credits 2019

Production Design and Art Direction United Scenic Artists, Local 829 IATSE 505 Court Street 7P, Brooklyn NY 11231 NYC 212 9797761 Los Angeles 310 3981982 [email protected] IMDB: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0919860/ LINKEDIN: www.linkedin.com/in/wellerdesign www.wellerdesign.com Production Design and Art Direction for film, television and theater. Extensive experience in single and multi camera art direction for features and network/cable television. Skillful, meticulous budgeting combined with quick and accurate drafting. Expertise in assembling and managing crews. Multiple Emmy Awards. Series NEW AMSTERDAM – Network Series - NBC UNIVERSAL 2019 Art Director ARMISTEAD MAUPIN’S TALES OF THE CITY – Mini Series- NETFLIX 2019 Assistant Art Director FIRST WIVE’S CLUB – PARAMOUNT NETWORK 2018 Art Director JESSICA JONES SEASON 3 - MARVEL PRODUCTIONS - NETFLIX 2018 Assistant Art Director JULIE’S GREENROOM – JIM HENSON PRODUCTIONS - NETFLIX –2016 Art Director QUANTICO – ABC - 2016 Assistant Art Director Feature Film LOST GIRLS – NETFLIX 2018 Art Director THE COMMUTER – LIONSGATE -2017 Assistant Art Director BRAWL IN CEL BLOCK 99 - RLJE FILMS - 2017 Art Department THE PERFECT GENTLEMAN – SHORT - 2010 Production Design BAD LIEUTENANT –ARIES FILMS -1992 Set Designer THE RAPTURE - FINE LINE FEATURES - 1991 Set Designer THE BLOODHOUNDS OF BROADWAY – COLUMBIA PICTURES - 1989 Assistant Art Director Live Events THE NEW LEVANT - KENNEDY CENTER 2018 GLAMOUR WOMEN OF THE YEAR- CONDE NAST Carnegie Hall 2016, 2017 ALICIA KEYS FOR VEUVE CLIQUOT – Liberty -

Framing Malaysia in the News Coverage of Indonesian Television

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 7 No 2 S1 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy March 2016 Framing Malaysia in the News Coverage of Indonesian Television Hamedi M. Adnan Amri Dunan Department of Media Studies, Faculty of Art and Social Sciences of Malaya University, 50603 Kuala Lumpur [email protected] Doi:10.5901/mjss.2016.v7n2s1p45 Abstract During the administration period of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY), Indonesia-Malaysia relationship became worse due to certain issues. There are three important issues affected relationship between Indonesia-Malaysia—political issue (Ambalat issue), economic issue (Indonesian migrant worker-TKI) and cultural issue (Pendet dance). The question rise up in Indonesia- Malaysia relationship caused by the response and the sensitively from Indonesian which affected by the media framing, included media television. This research is to identify how framing is created and identify the media television framing. This research uses framing analysis of ‘Television News’ model developed from Gamson & Mogdiliani (1989) model and uses the inductive qualitative analysis process developed from the model of Van Gorp (2005/2010). The model refers to the identification method in verbal framing or nonverbal framing with the matrix method. In-depth interviews were conducted to 12 peoples— each four from television stations Metro TV, TV One and TVRI. Each of them consists of a reporter, cameraman, producer and redaction leader. This in-depth interview proposed to know ‘how’ and ‘why’ the verbal and nonverbal framing is done by the stations. Triangulation between framing analysis of ‘television news’ model, in-depth interview and the observation shows that the basic ideology such as nationalism from the media owner affect the media framing on Malaysia.