Connections: the Quarterly Journal, Vol.9, No.4, Fall 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iraq's Oil Sector

June 14, 2014 ISSUE BRIEF: IRAQ’S OIL SECTOR BACKGROUND Oil prices rise on Iraq turmoil Oil markets have reacted strongly to the turmoil in Iraq, the world’s seventh largest oil producer, in recent weeks. International Brent oil prices hit 9-month highs over $113 a barrel on June 13 following the takeover by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) of Mosul in the north as well as some regions further south with just a few thousand fighters. ISIS has targeted strategic oil operations in the past, attacking and shutting the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline. In Syria, the group holds the Raqqa oil field. POTENTIAL GROWTH The OPEC nation is expected to be largest contributor to global oil supplies through 2035 Iraq’s potential to increase oil production in the coming decades is seen by analysts as a key component to global growth. The IEA's 2013 World Energy Outlook forecasts Iraqi crude and NGL production to ramp up to 5.8 million b/d by 2020 and to 7.9 million b/d by 2035 in the base case scenario, making it the single largest contributor to global oil supply growth through 2035. Iraq produced roughly 3.4 million b/d in May, according to the IEA. The IEA’s medium-term outlook forecasts Iraqi production could reach 4.8 million b/d by 2018. OIL RESERVES Vast reserves are among the cheapest to develop and produce in the world Iraq has the world's fifth largest proven oil reserves, with estimates ranging between 141 billion and 150 billion barrels. -

End of the Concessionary Regime: Oil and American Power in Iraq, 1958‐1972

THE END OF THE CONCESSIONARY REGIME: OIL AND AMERICAN POWER IN IRAQ, 1958‐1972 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Brandon Wolfe‐Hunnicutt March 2011 © 2011 by Brandon Roy Wolfe-Hunnicutt. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/tm772zz7352 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Joel Beinin, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Barton Bernstein I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Gordon Chang I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Robert Vitalis Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. -

China in the Transition to a Low-Carbon Economony

EAST-WEST CENTER WORKING PAPERS Economics Series No. 109, February 2010 China in the Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy ZhongXiang Zhang WORKING PAPERS WORKING The East-West Center promotes better relations and understanding among the people and nations of the United States, Asia, and the Pacific through coopera- tive study, research, and dialogue. Established by the U.S. Congress in 1960, the Center serves as a resource for information and analysis on critical issues of com- mon concern, bringing people together to exchange views, build expertise, and develop policy options. The Center’s 21-acre Honolulu campus, adjacent to the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, is located midway between Asia and the U.S. mainland and features research, residential, and international conference facilities. The Center’s Washington, D.C., office focuses on preparing the United States for an era of growing Asia Pacific prominence. The Center is an independent, public, nonprofit organi zation with funding from the U.S. government, and additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, foundations, corporations, and governments in the region. East-West Center Working Papers are circulated for comment and to inform interested colleagues about work in progress at the Center. For more information about the Center or to order publications, contact: Publication Sales Office East-West Center 1601 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96848-1601 Telephone: 808.944.7145 Facsimile: 808.944.7376 Email: [email protected] Website: EastWestCenter.org EAST-WEST CENTER WORKING PAPERS Economics Series No. 109, February 2010 China in the Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy ZhongXiang Zhang ZhongXiang Zhang is a Senior Fellow at the East-West Center. -

BP in Rumaila Pdf / 113.7 KB

BP in Rumaila Speaker: Michael Daly Title: head of exploration Speech date: 15 February 2010 Venue: International Petroleum Week, London Mr Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen. I’d like to thank the organisers here at the Energy institute for this kind invitation to BP to talk about our recent move into Iraq. In 1953 the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), of which BP was a key partner, discovered oil in the Rumaila prospect of Southern Iraq. In 2009, BP signed a Producing Field Technical Service Contract to grow production and recovery from the field that it helped discover more than 50 years ago. In this talk, I will share with you BP’s perspective on Rumaila, its context, reservoirs and resources, the nature of the BP relationship with Iraq and outline a little of what the future looks like. Context Firstly, it is worth considering the geology and tectonic make-up of the whole Middle Eastern oil and gas province, and how Rumaila fits into it. The image shows the high Zagros Mountains passing southwards into the foothills of Kurdistan in Iraq, and Khuzestan in Iran. The foothills give way southwards to the subdued landscape of the Zagros foreland basin that is partly submerged beneath the present day Gulf. The Zagros foothills and foreland basin hold the greatest concentration of oil in the world. It was in the Zagros foothills that Middle Eastern oil was first discovered in the fold structure of Masjid y Suleiman in Persia in 1908; natural oil seepages and surface structures were the clues that led to the discovery. -

South-South Special-What a Globalizing China Means for Latam

Ben Laidler LatAm Equity Strategist and Head of Americas Research HSBC Securities (USA) Inc. +1 212 525 3460 [email protected] Equity, Equity Strategy, and Economics Ben Laidler, HSBC’s LatAm equity strategist and Head of Americas Research, joined the firm in 2012. He leads a November 2013 team of regional equity strategists based in Sao Paulo, Mexico City and New York. Ben started covering emerging market equities in 1994 and has worked on both the buy side and sell side. He is a graduate of the LSE and Cambridge University, and an Associate of the AIIMR. Qu Hongbin Co-Head Asian Economics Research & Chief China Economist The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited +852 2822 2025 [email protected] Qu Hongbin is Managing Director, Co-Head of Asian Economic Research, and Chief Economist for Greater China. He has been an economist in financial markets for 17 years, the past eight at HSBC. Hongbin is also a deputy director of research at the China Banking Association. He previously worked as a senior manager at a leading South-South Special Chinese bank and other Chinese institutions. Todd Dunivant* Head of Banks Research, Asia-Pacific The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited What a globalizing China means for LatAm +852 2996 6599 [email protected] Todd Dunivant is Head of Banks research for Asia Pacific. He joined HSBC in 2005, with more than 20 years’ experience in banking and management consulting to banks. Todd has more 15 years of experience in emerging market banking systems primarily in Asia, Latin American and emerging Europe. -

China National Petroleum Corporation Energize ∙ Harmonize ∙ Realize

China National Petroleum Corporation Energize ∙ Harmonize ∙ Realize China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) is an integrated international energy company, with businesses covering oil and gas operations, oilfield services, engineering and construction, equipment manufacturing, financial services and new energy development. Contents Message from the Chairman 03 Report of the President 04 Operation Highlights 06 Board of Directors • Top Management • Organization 07 Comprehensively Deepen Corporate Reforms to Boost Steady and Sound Growth 10 Deepening International Oil and Gas Cooperation Under the Belt and Road Initiative 12 Phase I of Yamal LNG Project Became Operational 13 2017 Industry Review and Outlook 14 Safety and Environmental Protection 16 Human Resources 20 Technology and Innovation 24 Annual Business Overview 28 Financial Statements 52 Major Events 62 Glossary 64 2017 Annual Report 02 Message from the Chairman 2017 Annual Report In 2017, the company reviewed and launched a range of key reform initiatives and made new progress in reforms with regards to corporate governance, work process of the Board of Directors, specialized restructuring and mixed ownership etc. Meanwhile, the company pushed forward the reform of its R&D system and implemented the innovation strategy, resulting in a wide range of achievements in technology development and application. The reform of overseas operation systems, ongoing restructuring of oilfield services and optimization of headquarters functions moved forward as scheduled. The ownership reform towards the structure of a limited liability company was successfully completed. The pilot program for promoting autonomy in management advanced steadily. China Petroleum Engineering Co., Ltd. (CPEC) and CNPC Capital Co., Ltd. were publicly listed. During the convening of Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing in May 2017, CNPC held the first Belt and Road Roundtable for Oil and Gas Cooperation to share ideas and promote international cooperation in the oil and gas circle. -

China National Petroleum Corporation

2015 Annual Report2015 Annual 2015 China National Petroleum Corporation Corporation Petroleum China National China National Petroleum Corporation 9 Dongzhimen North Street, Dongcheng District, Beijing 100007, P. R. China www.cnpc.com.cn Energize ∙ Harmonize ∙ Realize Contents 03 Message from the Chairman 04 Board of Directors · Top Management · Organization 06 Year in Brief 09 Operation Highlights 10 2015 Industry Review 12 Safety, Environment, Quality and Energy Conservation 16 Human Resources 18 Technology 22 Annual Business Review 22 Exploration and Production 28 Natural Gas and Pipelines 30 Refining and Chemicals 32 Marketing and Sales 34 Overseas Oil and Gas Operations 37 International Trade 38 Oilfield Services, Engineering & Construction, and Equipment Manufacturing 44 Financial Statements 52 Major Events 55 Glossary 2015 Annual Report 02 Message from the Chairman 2015 Annual Report Enhanced technological innovation capability: We maintained world leading position in exploration and development technologies, achieved leaping development in refining and petrochemicals technologies and became a frontrunner in oil and gas storage & transportation technologies by continually improving our innovation system, and promoting the development of key theories and applied techniques. In particular, "Theoretical and technological innovations for the exploration and development of ultra-low-permeability tight oil and gas reservoirs" was awarded the first-class National Science and Technology Progress Award. Effectively fulfilling green development: With the corporate mission of “Caring for Energy, Caring for You”, we have been upholding the sustainability concept of safe, clean and energy-saving development. We continue to change the mode of energy production and consumption, keep improving our HSE system, fulfill our corporate social responsibility and promote emission reduction, energy conservation and environmental protection, so as to fight climate change and boost socioeconomic development where we operate. -

Rumaila and West-Qurna Oil Fields South Iraq, Unpublished Msc Thesis

Vol.52, No.1, 2019 A MODIFIED WATER INJECTION TECHNIQUE TO IMPROVE OIL RECOVERY: MISHRIF CARBONATE RESERVOIRS IN SOUTHERN IRAQ OIL FIELDS, CASE STUDY Awadees M.R. Awadeesian1, Salih M. Awadh2, Moutaz A. Al-Dabbas2, Mjeed M. Al-Maliki3, Sameer N. Al-Jawad4 and Abdul-Kareem S. Hussein5 1Carbonate Stratigraphy, Reservoir Development Consultant at Private 2Department of Geology, College of Sciences, University of Baghdad 3Geologic studies Dept., Basra Oil Company 4Reservoirs Directorate, Ministry of Oil 5Reservoir Department, Basra Oil Company Received: 4 July 2018; accepted: 21 September 2018 ABSTRACT A modified water injection technique has organized by this study to improve oil recovery of the Mishrif reservoirs using polymerized alkaline surfactant water (PAS- Water) injection. It is planned to modify the existing water injection technology, first to control and balance the hazardous troublemaker reservoir facies of fifty-micron pore sizes with over 500 millidarcies permeability, along with the non-troublemaker types of less than twenty micron pore sizes with 45 to 100 millidarcies permeability. Second to control Mishrif reservoirs rock-wettability. Special core analysis under reservoir conditions of 2250 psi and 90 °C has carried out on tens of standard core plugs with heterogeneous buildup, using the proposed renewal water flooding mechanism. The technique assures early PAS-water injection to delay the water- breakthrough from 0.045 – 0.151 pore volumes water injected with 8 – 25% oil recovery, into 0.15 – 0.268 pore volumes water injected with 18 to 32% improved oil recovery. As well as, crude oil-in-water divertor injection after breakthrough, within 0.3 to oil0.65 – 0.85-pore volume of water injected to decrease water cut 1 four 0 to 15%. -

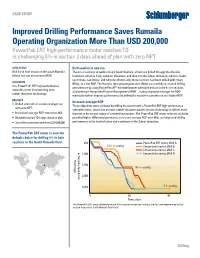

Improved Drilling Performance Saves Rumaila

CASE STUDY Improved Drilling Performance Saves Rumaila Operating Organization More Than USD 200,000 PowerPak ERT high-performance motor reaches TD in challenging 8½-in section 3 days ahead of plan with zero NPT CHALLENGE Drill section in one run Drill 8½-in hole section in the South Rumaila The 8½-in sections of wells in Iraq’s South Rumaila oil field are drilled through the Shuaiba field in one run at increased ROP. formation, which is hard, compact limestone, and then into the Zubair formation, which is made up of shale, sandstone, and siltstone. Historically, these sections had been drilled with rotary SOLUTION BHAs, at a low ROP. The Rumaila Operating Organization (ROO) successfully increased drilling Use PowerPak* ERT high-performance performance by using PowerPak XP* extended power steerable motors in the 8½-in sections. steerable motor incorporating even Schlumberger Integrated Project Management (IPM)—acting as project manager for ROO— rubber thickness technology. wanted to further improve performance by drilling the section in just one run at a higher ROP. RESULTS Increase average ROP ■ Drilled entire 8½-in section in single run Those objectives were achieved by drilling the section with a PowerPak ERT high-performance with zero NPT. steerable motor, which has an even-rubber-thickness power section technology to deliver more ■ Increased average ROP more than 36%. than twice the torque output of conventional motors. The PowerPak ERT motor reduced stick/slip, ■ Reached section TD 3 days ahead of plan. provided higher differential pressures, increased average ROP over 36%, and improved drilling ■ Saved the customer more than USD 200,000. -

Tar Mats) Deposits and Forming Mechanism in the Main Pay of the Zubair Formation in North Rumaila Oil Field, Southern Iraq

International Journal of Mining Science (IJMS) Volume 5, Issue 1, 2019, PP 1-10 ISSN 2454-9460 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-9460.0501001 www.arcjournals.org Identification of Heavy Oil (Tar Mats) Deposits and Forming Mechanism in the Main Pay of the Zubair Formation in North Rumaila Oil Field, Southern Iraq Shaymaa Mohammed J.1*, Amna M Handhal2 1,2University of Basrah, Geology Department, Basrah, Iraq *Corresponding Author: Shaymaa Mohammed J., University of Basrah, Geology Department, Basrah, Iraq Abstract: Zubair Formation in the giant oil field of North Rumaila in southern Iraq is a good oil reservoir that consists of friable porous sandstone intercalated with thin shale and siltstone layers. The main pay of this reservoir has a thick variable Tar mat (asphaltic) interval near oil–water contact and influences reservoir production and the aquifer support. To delineate Tar mat zones in the reservoir unit of Zubair Formation, different paradigms were followed in this study including description of the cutting and core samples and borehole logs. Numbers of wells were selected to identify the thickness of Tar mat zone in the eastern and western flanks by core and rock cutting samples in addition to the study of borehole logs such as resistivity and nuclear magnetic resonance logs. Asphaltenes are normally dissolved in hydrocarbons in the form of suspension. Then, we study a number of processes can cause these compounds to drop out of suspension at certain zones and the possible mechanisms of Tar mat formation in the considered reservoirs. 1. INTRODUCTION Zubair sandstone reservoir has a variable thick Tar mat (asphaltic) interval near oil water contact and has an impact of the aquifer support of the reservoir. -

Carbon Democracy. Political Power in the Age Of

Carbon Democracy Carbon Democracy political power in the age of oil Timothy Mitchell First published by Verso 2011 © Timothy Mitchell 2011 All rights reserved e moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Le9 Books ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-745-0 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Typeset in Minion Pro by Hewer UK Ltd, Edinburgh Printed in the US by Maple Vail To Adie and JJ Contents Acknowledgements ix Introduction 1 1 Machines of Democracy 12 2 e Prize from Fairyland 43 3 Consent of the Governed 66 4 Mechanisms of Goodwill 86 5 Fuel Economy 109 6 Sabotage 144 7 e Crisis at Never Happened 173 8 McJihad 200 Conclusion: No More Counting On Oil 231 Bibliography 255 Index 271 Acknowledgements I have beneK ted from the comments and criticisms of participants in numerous seminars and lectures where parts of this work were presented, and from more extended discussions with Andrew Barry, Michel Callon, GeoL Eley, Mahmood Mamdani and Robert Vitalis. A number of former students shared with me their work on related topics, and in several cases contributed their assistance to my own research; these include Katayoun ShaK ee, Munir Fakher Eldin, Canay Özden, Firat Bozçali, Ryan Weber and Sam Rubin. -

Technical Service Contract for the Rumaila Oil Field

BP/CNPC Comments 27 July 2009 Without Prejudice TECHNICAL SERVICE CONTRACT FOR THE RUMAILA OIL FIELD BETWEEN SOUTH OIL COMPANY OF THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ AND BP IRAQ LIMITED AND CNPC INTERNATIONAL (IRAQ) LIMITED AND SOMO BP/CNPC Comments 27 July 2009 Without Prejudice TECHNICAL SERVICE CONTRACT FOR THE RUMAILA OIL FIELD TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLE 1 – DEFINITIONS..........................................................................................................3 ARTICLE 2 – SCOPE OF CONTRACT.......................................................................................10 ARTICLE 3 – TERM OF CONTRACT .........................................................................................12 ARTICLE 4 – SIGNATURE BONUS ...........................................................................................12 ARTICLE 5 – RELINQUISHMENT ..............................................................................................12 ARTICLE 6 – MINIMUM WORK OBLIGATION ..........................................................................12 ARTICLE 7 – SOC’S ASSISTANCE ...........................................................................................13 ARTICLE 8 – TERMINATION......................................................................................................15 ARTICLE 9 – CONDUCT OF PETROLEUM OPERATIONS ......................................................16 ARTICLE 10 – ASSOCIATED GAS ............................................................................................21 ARTICLE 11 – DEVELOPMENT