Clifford-Looking Back at Watkins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yosemite National Park U.S

National Park Service Yosemite National Park U.S. Department of the Interior The Ahwahnee Comprehensive Rehabilitation Plan Where is The Ahwahnee is located in Yosemite Valley in Yosemite National Park. The Ahwahnee area the project includes a National Historic Landmark hotel, as well as guest cottages, an employee dormitory, and located? associated grounds and landscaping. Built in 1927, The Ahwahnee hotel is an iconic landmark and is used year-round by both overnight and day visitors to Yosemite Valley. After more than 80 years in service, the hotel and associated structures are in need of rehabilitation because: Why Facilities at The Ahwahnee are not fully compliant with the most recent building and undertake this planning accessibility codes, including: International Building Code (IBC) effort? National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Code Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and IBC seismic requirements; and Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) standards. Many of the electrical, plumbing and mechanical systems serving The Ahwahnee facilities are aging and need to be replaced and updated. Some historic hotel finishes and landscape components are time-worn or have been altered over the years, potentially affecting the historic integrity of this property. The current operational layout of some working areas reduces the efficiency of providing a high level of visitor services. The purpose of this project is to develop a comprehensive plan for phased, long-term rehabilitation of The Ahwahnee National Historic Landmark hotel and associated guest cottages, employee dormitory, What does and landscaped grounds in order to: this plan propose? Restore, preserve, and protect the historic integrity and character-defining features of The Ahwahnee by rehabilitating aged or altered historic finishes and contributing landscape features. -

How Did Public Lands Come to Be?

Module 2 How did Public Lands Come to Be? Main Takeaways Public lands in the United States were created within the context of complex social and historical movements and mindsets. A more complete understanding of public lands requires acknowledgement of the people and cultures who have been negatively affected throughout the complex history of public lands. © Kevin McNeal This module will examine the history of public lands in the Historical Overview United States. It is important for people to know the history of public lands so that we can understand the perspectives of Time Immemorial others who have different types of connections to these places. When conservationists talk about the establishment of public lands in the United States, they sometimes focus on governmental decisions to protect land for future generations. However, the protection of lands as public did not occur in a vacuum. The conservation of these places reflects the larger social, cultural, and political forces and events of United States history. These influences are as diverse as the lands themselves. With this module, we try to provide a more comprehensive history of public lands. In doing so, we try to include the stories of some of the people and communities that have been History is conveyed in different ways by different cultures. For left out of the traditional Euro-American narrative. the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas, history begins with time immemorial - time before the reach of human memory. However, the history presented in no way encompasses the The history of connection to the land before memory is passed complete story of the people who have been impacted by public on through oral tradition. -

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park July 29, 2015 - September 1, 2015 1, September - 2015 29, July Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where NPS Photo NPS 1904. Grove, Mariposa Monarch, Fallen the astride Soldiers” “Buffalo Cavalry 9th D, Troop Volume 40, Issue 6 Issue 40, Volume America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Shuttle Yosemite The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking Village Day-use Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Half Dome Picnic Area 11 P1 1 8836 ft North 2693 m Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Lodge Day-use Parking Pines Walk-In (Open May 22, 2015) Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Village Day-use Parking Pines Beach E7 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l E4 Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d R V iver E6 Nevada To & Fall The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

National Register Off Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

N. H. L. ARCHITECTURE IN THE PARKS NPS Form 10400 (342) OHB So. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS UM only National Register off Historic Places received Inventory—Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1 • Name__________________ historic The Ahwahnee Hotel and or common_____________________________________ 2. Location street & number Yosemite Valley __ not for publication city town Yosemite National Park . vicinity of state California code 06 county Mariposa code 043 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use __ district __ public x occupied __ agriculture __museum _x building(s) _x. private __ unoccupied __ commercial —— park __ structure __both __ work in progress __ educational __ private residence __site Public Acquisition Accessible __ entertainment __ religious __ object __ in process x yes: restricted __ government __ scientific __ being considered __ yes: unrestricted __ industrial __transportation __"no __ military _x_ other: Luxury Hotel 4. Owner off Property name Yosemite Park and Curry Company street & number city, town Yosemite National Park __ vicinity of state California 5. Location off Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Mariposa County Courthouse street A number city, town Mariposa state California 6. Representation in Existing Surveys__________ title National Register of Historic Places has this property been determined eligible? __ yes __ no 1977 .state __county local depository for survey records National Park Service cHy, town Washington state D - C. 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered x original site __ ruins x altered __ moved date . -

Yosemite National Park Foundation Overview

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Yosemite National Park California Contact Information For more information about Yosemite National Park, Call (209) 372-0200 (then dial 3 then 5) or write to: Public Information Office, P.O. Box 577, Yosemite, CA 95389 Park Description Through a rich history of conservation, the spectacular The geology of the Yosemite area is characterized by granitic natural and cultural features of Yosemite National Park rocks and remnants of older rock. About 10 million years have been protected over time. The conservation ethics and ago, the Sierra Nevada was uplifted and then tilted to form its policies rooted at Yosemite National Park were central to the relatively gentle western slopes and the more dramatic eastern development of the national park idea. First, Galen Clark and slopes. The uplift increased the steepness of stream and river others lobbied to protect Yosemite Valley from development, beds, resulting in formation of deep, narrow canyons. About ultimately leading to President Abraham Lincoln’s signing 1 million years ago, snow and ice accumulated, forming glaciers the Yosemite Grant in 1864. The Yosemite Grant granted the at the high elevations that moved down the river valleys. Ice Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove of Big Trees to the State thickness in Yosemite Valley may have reached 4,000 feet during of California stipulating that these lands “be held for public the early glacial episode. The downslope movement of the ice use, resort, and recreation… inalienable for all time.” Later, masses cut and sculpted the U-shaped valley that attracts so John Muir led a successful movement to establish a larger many visitors to its scenic vistas today. -

Yosemite Guide @Yosemitenps

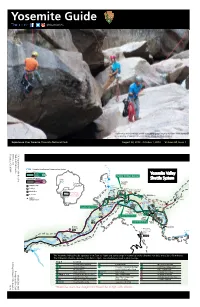

Yosemite Guide @YosemiteNPS Yosemite's rockclimbing community go to great lengths to clean hard-to-reach areas during a Yosemite Facelift event. Photo by Kaya Lindsey Experience Your America Yosemite National Park August 28, 2019 - October 1, 2019 Volume 44, Issue 7 Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Summer-only Route: Upper Hetch Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Hetchy Shuttle Fall Yosemite Tuolumne Village Campground Meadows Lower Yosemite Parking The Ansel Fall Adams Yosemite l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area Picnic Area Valley l T Area in inset: al F e E1 t 5 Restroom Yosemite Valley i 4 m 9 The Ahwahnee Shuttle System se Yo Mirror Upper 10 3 Walk-In 6 2 Lake Campground seasonal 11 1 Wawona Yosemite North Camp 4 8 Half Dome Valley Housekeeping Pines E2 Lower 8836 ft 7 Chapel Camp Yosemite Falls Parking Lodge Pines 2693 m Yosemite 18 19 Conservation 12 17 Heritage 20 14 Swinging Center (YCHC) Recreation Campground Bridge Rentals 13 15 Reservations Yosemite Village Parking Curry Upper Sentinel Village Pines Beach il Trailhead E6 a Curry Village Parking r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M E4 ey ses erce all only d Ri V ver E5 Nevada Fall To & Bridalveil Fall d oa R B a r n id wo a a lv W e i The Yosemite Valley Shuttle operates from 7am to 10pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Superintendent's Message

Superintendent’s Message Welcome! I am so grateful to have you here to help caretake Yosemite during these unprecedented circumstances. Thank you for your commitment to public service and public land during this challenging time. On behalf of the leadership team, we are deeply honored to have you as part of our world-class team. While not new to the park, I began here as the Acting Superintendent this past January. I’ve spent my career in the park service and most recently came from Point Reyes National Seashore where I’ve been superintendent since 2010. I have always been inspired at every opportunity to work with Yosemite’s passionate and talented staff and my experience since January has only underscored this sentiment. My vision for Yosemite in Summer 2020 is first and foremost to ensure the safety of our staff and visitors. Our physical and mental health are Commented [KN1]: I would say here something like, “I critical to our success as a park. We live closely with each other and with the dynamic natural landscape, both of have been impressed by the speak up culture here at which require us to be uniquely aware and resilient. I fully encourage each and every one of you to take Yosemite. If you ever feel unsafe in the task you are given, advantage of the support services available to you as an employee with the understanding that daily peer support please be sure to speak up and let your supervisor know.” is the most effective strategy benefitting us at individual and organizational levels. -

Yosemite Forest Dynamics Plot

REFERENCE COPY - USE for xeroxing historic resource siuay VOLUME 3 OF 3 discussion of historical resources, appendixes, historical base maps, bibliography YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK / CALIFORNIA Historic Resource Study YOSEMITE: THE PARK AND ITS RESOURCES A History of the Discovery, Management, and Physical Development of Yosemite National Park, California Volume 3 of 3 Discussion of Historical Resources, Appendixes, Historical Base Maps, Bibliography by Linda Wedel Greene September 1987 U.S. Department of the Interior / National Park Service b) Frederick Olmsted's Treatise on Parks ... 55 c) Significance of the Yosemite Grant .... 59 B. State Management of the Yosemite Grant .... 65 1. Land Surveys ......... 65 2. Immediate Problems Facing the State .... 66 3. Settlers' Claims ........ 69 4. Trails ........%.. 77 a) Early Survey Work ....... 77 b) Routes To and Around Yosemite Valley ... 78 c) Tourist Trails in the Valley ..... 79 (1) Four-Mile Trail to Glacier Point ... 80 (2) Indian Canyon Trail ..... 82 (3) Yosemite Fall and Eagle Peak Trail ... 83 (4) Rim Trail, Pohono Trail ..... 83 (5) Clouds Rest and Half (South) Dome Trails . 84 (6) Vernal Fall and Mist Trails .... 85 (7) Snow Trail ....... 87 (8) Anderson Trail ....... (9) Panorama Trail ....... (10) Ledge Trail 89 5. Improvement of Trails ....... 89 a) Hardships Attending Travel to Yosemite Valley . 89 b) Yosemite Commissioners Encourage Road Construction 91 c) Work Begins on the Big Oak Flat and Coulterville Roads ......... 92 d) Improved Roads and Railroad Service Increase Visitation ......... 94 e) The Coulterville Road Reaches the Valley Floor . 95 1) A New Transportation Era Begins ... 95 2) Later History 99 f) The Big Oak Flat Road Reaches the Valley Floor . -

Yosemite Roads and Bridges Man WAY B M Eaiimum

Yosemite's Bridges STGNEMLAN BRIDGE CONSTRUCTION - 1932 YOSEMITE FALLS Yosemite Village A variety of vehicular bridges span the main streams and lesser tributaries in the park. The oldest is the covered bridge at This structure exemplifies the National Park Service Rustic man WAY B m EAiimum Wawona, built as an open-deck structure in 1868 by Galen Style of architecture. Built of reinforced concrete, Ahwahnee Hotel Clark, the first settler and state-appointed Guardian of the the bridge is faced with native granite to blend s Yosemite Grant. In the 1870s it was converted to a covered in with its natural setting. Equestrian bridge by the Washburn brothers, natives of Vermont, who tunnels were designed in conjunction supposedly had it altered to remind them of their home state. with a new park bridle path. Yosemite Lodge Yosemite Rehabilitated by the Park Service in 1956, it can be seen today Drawn by David Fleming, at the Pioneer Yosemite History Center. HAER, 1991 Roads and Bridges Yosemite National Park, California Early bridges were wood and metal trusses. The previous Sentinel Bridge was an uncommon iron bowstring-arch truss. YRL WAWONA COVERED BRIDGE, 1868 The Wawona Tunnel was the longest vehicular tunnel in the Drawn by Dione DeMartelaere, HAER, 1991 West when completed in 1933. Significant for its state-of- Original Appearance the-art engineering, the tunnel played a greater role in Construction of retaining wall on Big Oak Flat Drawn by Dione DeMartelaere and preserving the visible landscape of Yosemite Valley. Road, 1939. YRL Marie-Claude LeSauteur, HAER 1991 Over the ensuing years more timber and iron trusses were built, but these eventually gave way to reinforced concrete structures; 1. -

Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Devils Postpile Formation and Talus

Nature and History on the Sierra Crest: Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Devils Postpile formation and talus. (Devils Postpile National Monument Image Collection) Nature and History on the Sierra Crest Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Christopher E. Johnson Historian, PWRO–Seattle National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 2013 Production Project Manager Paul C. Anagnostopoulos Copyeditor Heather Miller Composition Windfall Software Photographs Credit given with each caption Printer Government Printing Office Published by the United States National Park Service, Pacific West Regional Office, Seattle, Washington. Printed on acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America. 10987654321 As the Nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship and citizen participation in their care. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under U.S. administration. -

An Indivisible and Living Whole: Do We Value Nature Enough to Grant It Personhood?

03_ATHENS_EDITEDPROOF (DO NOT DELETE) 11/8/2018 2:32 PM An Indivisible and Living Whole: Do We Value Nature Enough to Grant It Personhood? Allison Katherine Athens In 1972, in his dissent to the majority’s decision in Sierra Club v. Morton, Justice Blackmun posed a question: “Must our law be so rigid and our procedural concepts so inflexible that we render ourselves helpless when the existing methods and the traditional concepts do not quite fit and do not prove to be entirely adequate for new issues?” Forty years later, Aotearoa New Zealand’s parliament answered in the negative. Responding to the New Zealand Crown government’s historic failure to meet their treaty responsibilities with Māori iwi (tribes) and current fears of environmental degradation, the New Zealand Crown government found flexibility in their legal system to accommodate Māori views of nature as a living entity that cannot be owned and used as property. By transforming a former national park and an economically important river from property to legal persons under the guardianship of the interested Māori tribe, the New Zealand Crown government eschewed rigidity in order to meet their treaty obligations while also safeguarding the best interest of each natural feature as an ecological system. In the following Note, I borrow from feminist theory and environmental philosophy to examine how the categories of nature and personhood function within a cultural context to support the status quo of nature as property. I conduct a detailed examination of the case of Lavinia Goodell, a woman denied admittance to the bar in 1875, in order to show how cultural attitudes determine categorical boundaries, indicating that nature can gain legal personhood based on changing cultural norms. -

Things to Do and See in Yosemite SUGGESTIONS ACCORDING to the TIME YOU HAVE

Yosemite Peregrine Lodge Encouraging Adventure And Defining Relaxation. Things to do and see in Yosemite SUGGESTIONS ACCORDING TO THE TIME YOU HAVE A man reportedly visited the park and approached John Muir to inquire what he should see as he only had one day to visit the park. John replied, “Sit down and cry lad”. I don’t know what the man ended up seeing or doing, but one thing is for sure no matter how long you have in the park you will be able to see a little bit of one of the most amazing places on earth. And that is worth any time you will spend here. The following are some suggestions on what to see and do given a certain amount of time. ONE HOUR Location: Yosemite Valley 1. Explore the Visitor center exhibits. Learn about Yosemite’s geology, history, and resources 2. Tour the reconstructed Native American Village behind the visitor center. Experience Ahwahnechee life. 3. Walk along the self guided changing Yosemite nature trail. Begin trail outside visitor center. 4. Visit the fascinating Native American cultural museum. See Yosemite’s extensive basket collection. 5. Walk to the base of the lower Yosemite Falls, best time of year is April-July, and October-November. 6. Ride the free shuttle bus around the east Valley with views of Half Dome and the Merced River. 7. Walk an easy trail to the base of Bridalveil Fall. 8. Enjoy Tunnel View on Highway 41. This is an awesome scenic view of the entire Yosemite Valley. TWO HOURS 1.