On the Greenhouse Effect Monday, March 12, 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Change and Human Health: Risks and Responses

Climate change and human health RISKS AND RESPONSES Editors A.J. McMichael The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia D.H. Campbell-Lendrum London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom C.F. Corvalán World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland K.L. Ebi World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, European Centre for Environment and Health, Rome, Italy A.K. Githeko Kenya Medical Research Institute, Kisumu, Kenya J.D. Scheraga US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, USA A. Woodward University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION GENEVA 2003 WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Climate change and human health : risks and responses / editors : A. J. McMichael . [et al.] 1.Climate 2.Greenhouse effect 3.Natural disasters 4.Disease transmission 5.Ultraviolet rays—adverse effects 6.Risk assessment I.McMichael, Anthony J. ISBN 92 4 156248 X (NLM classification: WA 30) ©World Health Organization 2003 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Marketing and Dis- semination, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications—whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution—should be addressed to Publications, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Statement Climate Change Greenhouse Effect

Western Region Technical Attachment No. 91-07 February 19, 1991 STATEMENT ON CLIMATE. CHANGE AND THE GREENHOUSE EFFECT STATEMENT ON CLIMATE CHANGE AND THE GREENHOUSE EFFECT by REGIONAL CLIMATE CENTERS High Plains Climate Center· University of Nebraska Midwestern Climate Center • Illinois State Water Survey Northeast Regional Climate Center - Cornell University Southern Regional Climate Center • Louisiana State University Southeastern Regional Climate Center • South Carolina Water Commission "'estern Regional Climate Center - Desert Research Institute March 1990 STATEMENT ON CLIMATE CHANGE AND THE GREENHOUSE EFFECT by Regional Climate Centers The Issue Many scientists have issued claims of future global climate changes towards warmer conditions as a result of the ever increasing global release of Carbon Dioxide (C02) and other trace gases from the burning of fossil fuels and from deforestation. The nation experienced an unexpected and severe drought in 1988 which continued through 1989 in parts of the western United States.Is there a connection between these two atmospheric issues? Was the highly unusual 1988-89 drought the first symptom of the climate change atmospheric scientists had been talking about for the past 10 years? Most of the scientific community say "no." The 1988 drought was probably not tied to the ever increasing atmospheric burden of our waste gases. The 1988 drought fits within the historical range of climatic extremes over the past 100 years. Regardless, global climate. change due to the greenhouse effect is an issue of growing national and international concern. It joins the acid rain and ozone layer issues as major atmospheric problems arising primarily from human activities. The term "Greenhouse Effect" derives from the loose analogy between the behavior of the absorbing trace gases in the atmosphere and the window glass in a greenhouse. -

Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Human Activities

4 Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Human Activities CO-CHAIRS D. Kupfer (Germany, Fed. Rep.) R. Karimanzira (Zimbabwe) CONTENTS AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY, AND OTHER HUMAN ACTIVITIES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 77 4.1 INTRODUCTION 85 4.2 FOREST RESPONSE STRATEGIES 87 4.2.1 Special Issues on Boreal Forests 90 4.2.1.1 Introduction 90 4.2.1.2 Carbon Sinks of the Boreal Region 90 4.2.1.3 Consequences of Climate Change on Emissions 90 4.2.1.4 Possibilities to Refix Carbon Dioxide: A Case Study 91 4.2.1.5 Measures and Policy Options 91 4.2.1.5.1 Forest Protection 92 4.2.1.5.2 Forest Management 92 4.2.1.5.3 End Uses and Biomass Conversion 92 4.2.2 Special Issues on Temperate Forests 92 4.2.2.1 Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Temperate Forests 92 4.2.2.2 Global Warming: Impacts and Effects on Temperate Forests 93 4.2.2.3 Costs of Forestry Countermeasures 93 4.2.2.4 Constraints on Forestry Measures 94 4.2.3 Special Issues on Tropical Forests 94 4.2.3.1 Introduction to Tropical Deforestation and Climatic Concerns 94 4.2.3.2 Forest Carbon Pools and Forest Cover Statistics 94 4.2.3.3 Estimates of Current Rates of Forest Loss 94 4.2.3.4 Patterns and Causes of Deforestation 95 4.2.3.5 Estimates of Current Emissions from Forest Land Clearing 97 4.2.3.6 Estimates of Future Forest Loss and Emissions 98 4.2.3.7 Strategies to Reduce Emissions: Types of Response Options 99 4.2.3.8 Policy Options 103 75 76 IPCC RESPONSE STRATEGIES WORKING GROUP REPORTS 4.3 AGRICULTURE RESPONSE STRATEGIES 105 4.3.1 Summary of Agricultural Emissions of Greenhouse Gases 105 4.3.2 Measures and -

Energy Budget: Earth’S Most Important and Least Appreciated Planetary Attribute by Lin Chambers (NASA Langley Research Center) and Katie Bethea (SSAI)

© 2013, Astronomical Society of the Pacific No. 84 • Summer 2013 www.astrosociety.org/uitc 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112 Energy Budget: Earth’s most important and least appreciated planetary attribute by Lin Chambers (NASA Langley Research Center) and Katie Bethea (SSAI) asking in the Sun on a warm day, it’s easy for know some species of animals can see ultraviolet people to realize that most of the energy on light and portions of the infrared spectrum. NASA Earth comes from the Sun; students know satellites use instruments that can “see” different Bthis as early as elementary school. We all know parts of the electromagnetic spectrum to observe plants use this energy from the Sun for photosyn- various processes in the Earth system, including the thesis, and animals eat plants, creating a giant food energy budget. web. Most people also understand the Sun’s energy The Sun is a very hot ball of plasma emitting large drives evaporation and thus powers the water cycle. amounts of energy. By the time it reaches Earth, this But many people do not realize the Sun’s energy it- energy amounts to about 340 Watts for every square self is also part of an important interconnected sys- meter of Earth on average. That’s almost 6 60-Watt tem: Earth’s energy budget or balance. This energy light bulbs for every square meter of Earth! With budget determines conditions on our planet — just all of that energy shining down on the Earth, how like the energy budget of other planets determines does our planet maintain a comfortable balance that conditions there. -

CO2 Mitigation Through Biofuels in the Transport Sector

ifeu - Institute for Energy and Environmental Research Heidelberg Germany CO2 Mitigation through Biofuels in the Transport Sector Status and Perspectives Main Report supported by FVV, Frankfurt and UFOP, Berlin CO2 Mitigation through Biofuels in the Transport Sector Status and Perspectives Main Report Heidelberg, Germany, August 2004 Authors Dr. Markus Quirin Dipl.-Phys. Ing. Sven O. Gärtner Dr. Martin Pehnt Dr. Guido A. Reinhardt This report was executed by IFEU – Institut für Energie- und Umweltforschung Heidelberg GmbH (Institute for Energy and Environmental Research Heidelberg) Wilckensstrasse 3, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany Tel: +49-6221-4767-0, Fax -19 E-Mail: [email protected] www.ifeu.de Funding organisations F V V – Research Association for Combustion Engines F V V e. V. im VDMA, Lyoner Straße 18, 60528 Frankfurt am Main, Germany www.fvv-net.de UFOP – Union for the Promotion of Oil and Protein Plants UFOP e. V., Reinhardtstraße 18, 10117 Berlin, Germany www.ufop.de FAT – German Association for Research on Automobile-Technique FAT e. V. im VDA, Westendstraße 61, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany www.vda.de/de/vda/intern/organisation/abteilungen/fat.html More information on this project can be found on www.ifeu.de/co2mitigation.htm Acknowledgements We thank the Research Association for Combustion Engines (Forschungsvereinigung Verbrennungskraftmaschinen e. V., FVV) that called this study into existence. Thanks are also due to the Union for the Promotion of Oil and Protein Plants (Union zur Förderung von Oel- und Proteinpflanzen e. V., UFOP) and the German Association for Research on Automobile-Technique (Forschungsvereinigung Automobiltechnik e. V., FAT) that, together with FVV, financed this research. -

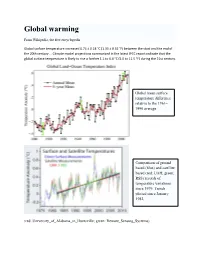

Global Warming

Global warming From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Global surface temperature increased 0.74 ± 0.18 °C (1.33 ± 0.32 °F) between the start and the end of the 20th century … Climate model projections summarized in the latest IPCC report indicate that the global surface temperature is likely to rise a further 1.1 to 6.4 °C (2.0 to 11.5 °F) during the 21st century. Global mean surface temperature difference relative to the 1961– 1990 average Comparison of ground based (blue) and satellite based (red: UAH; green: RSS) records of temperature variations since 1979. Trends plotted since January 1982. (red: University_of_Alabama_in_Huntsville; green: Remote_Sensing_Systems) Temperature is believed to have been relatively stable over the one or two thousand years before 1850, with regionally-varying fluctuations such as the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age. Two millennia of mea n surface temperatures according to different reconstructions, each smoothed on a decadal scale. The instrumental record and the unsmoothed annual value for 2004 are shown in black. Greenhouse gases The greenhouse effect is the process by which absorption and emission of infrared radiation by gases in the atmosphere warm a planet's lower atmosphere and surface. It was discovered by Joseph Fourier in 1824. Existence of the greenhouse effect as such is not disputed, even by those who do not agree that the recent temperature increase is attributable to human activity. The question is instead how the strength of the greenhouse effect changes when human activity increases the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Naturally occurring greenhouse gases have a mean warming effect of about 33 °C (59 °F). -

Information on Selected Climate and Climate-Change Issues

INFORMATION ON SELECTED CLIMATE AND CLIMATE-CHANGE ISSUES By Harry F. Lins, Eric T. Sundquist, and Thomas A. Ager U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 88-718 Reston, Virginia 1988 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL MODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: Office of the Director U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Books and Open-File Reports Section Reston, Virginia 22092 Box 25425 Federal Center, Bldg. 810 Denver, Colorado 80225 PREFACE During the spring and summer of 1988, large parts of the Nation were severely affected by intense heat and drought. In many areas agricultural productivity was significantly reduced. These events stimulated widespread concern not only for the immediate effects of severe drought, but also for the consequences of potential climatic change during the coming decades. Congress held hearings regarding these issues, and various agencies within the Executive Branch of government began preparing plans for dealing with the drought and potential climatic change. As part of the fact-finding process, the Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Water and Science asked the Geological Survey to prepare a briefing that would include basic information on climate, weather patterns, and drought; the greenhouse effect and global warming; and climatic change. The briefing was later updated and presented to the Secretary of the Interior. The Secretary then requested the Geological Survey to organize the briefing material in text form. The material contained in this report represents the Geological Survey response to the Secretary's request. -

Major Climate Feedback Processes Water Vapor Feedback Snow/Ice

Lecture 5 : Climate Changes and Variations Major Climate Feedback Processes Climate Sensitivity and Feedback Water Vapor Feedback - Positive El Nino Southern Oscillation Pacific Decadal Oscillation Snow/Ice Albedo Feedback - Positive North Atlantic Oscillation (Arctic Oscillation) Longwave Radiation Feedback - Negative Vegetation-Climate Feedback - Positive Cloud Feedback - Uncertain ESS200A ESS200A Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Snow/Ice Albedo Feedback Water Vapor Feedback Mixing Ratio = the dimensionless ratio of the mass of water vapor to the mass of dry air. Saturated Mixing Ratio tells you the maximum amount of water vapor an air parcel can carry. The saturated mixing ratio is a function of air temperature: the warmer the temperature the larger the saturated mixing ration. a warmer atmosphere can carry more water vapor The snow/ice albedo feedback is stronger greenhouse effect associated with the higher albedo of ice amplify the initial warming and snow than all other surface covering. one of the most powerful positive feedback This positive feedback has often been offered as one possible explanation for (from Earth’s Climate: Past and Future ) how the very different conditions of the ESS200A ESS200A Prof. Jin-Yi Yu ice ages could have been maintained. Prof. Jin-Yi Yu 1 Longwave Radiation Feedback Vegetation-Climate Feedbacks The outgoing longwave radiation emitted by the Earth depends on surface σ 4 temperature, due to the Stefan-Boltzmann Law: F = (T s) . warmer the global temperature larger outgoing longwave radiation been emitted by the Earth reduces net energy heating to the Earth system cools down the global temperature a negative feedback (from Earth’ Climate: Past and Future ) ESS200A ESS200A Prof. -

Biofuels, Greenhouse Gases and Climate Change. a Review Cécile Bessou, Fabien Ferchaud, Benoit Gabrielle, Bruno Mary

Biofuels, greenhouse gases and climate change. A review Cécile Bessou, Fabien Ferchaud, Benoit Gabrielle, Bruno Mary To cite this version: Cécile Bessou, Fabien Ferchaud, Benoit Gabrielle, Bruno Mary. Biofuels, greenhouse gases and climate change. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, Springer Verlag/EDP Sciences/INRA, 2009, pp.1-79. 10.1051/agro/2009039. cirad-00749753 HAL Id: cirad-00749753 http://hal.cirad.fr/cirad-00749753 Submitted on 8 Nov 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Agron. Sustain. Dev. Available online at: c INRA, EDP Sciences, 2010 www.agronomy-journal.org DOI: 10.1051/agro/2009039 for Sustainable Development Review article Biofuels, greenhouse gases and climate change. A review Cécile B1*,FabienF2, Benoît G2, Bruno M2 1 INRA Environment and agricultural crop research unit, 78 850 Thiverval-Grignon, France 2 INRA, US1158 Agro-Impact, 02 007 Laon-Mons, France (Accepted 23 September 2009) Abstract – Biofuels are fuels produced from biomass, mostly in liquid form, within a time frame sufficiently short to consider that their feed- stock (biomass) can be renewed, contrarily to fossil fuels. This paper reviews the current and future biofuel technologies, and their development impacts (including on the climate) within given policy and economic frameworks. -

Climate Change and the Greenhouse Effect

Climate change and the greenhouse effect A briefing from the Hadley Centre December 2005 Foreword The Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and I would like to thank Geoff Jenkins for putting Research has been a vital department of the Met together this presentation and the text on the notes Office since it was established in Bracknell in 1990, pages, and Chris Durman, Chris Folland, Jonathan and continues to be so after its move (with the rest Gregory, Jim Haywood, Lisa Horrocks (Defra), Tim of the Met Office headquarters) to Exeter in 2003. Johns, Cathy Johnson (Defra), Andy Jones, Chris Most of its 120 staff give presentations and lectures Jones, Gareth Jones, Richard Jones, Jason Lowe, on all aspects of the research. Many of these are to James Murphy, Peter Stott, Simon Tett, Ian Totterdell, conferences and workshops on the detailed Peter Thorne and David Warrilow (Defra), for their specialisms of climate change, such as the comments, which have greatly improved it. Fiona modelling of clouds or the interpretation of satellite Smith and the Met Office Design Studio handled measurements of atmospheric temperatures. But the layout and production. Consistent funding from others are to less specialised audiences, including the Global Atmosphere Division of the UK those from Government — ministers and senior Department of the Environment, Food and Rural policymakers — industry and commerce, pressure Affairs, and the Government Meteorological groups and the media, in each case from the UK Research programme over the last 15 years, has and overseas. enabled us to plan a sensible long-term research strategy. Finally, I would thank all members of the In 1999 we collected some of the slides that had Hadley Centre, and those from other institutes, for been drawn up to give these talks — mostly based letting us use their results here. -

Changing Climate a Guide for Teaching Climate Change in Grades 3 to 8 the Climate System 1 and Greenhouse Effect by Lindsey Mohan and Jenny D

ENVIRONMENTAL LITERACY TEACHER GUIDE SERIES Changing Climate A Guide for Teaching Climate Change in Grades 3 to 8 The Climate System 1 and Greenhouse Effect by Lindsey Mohan and Jenny D Ingber “Climate is what you increased risk of drought, wildfires, and of this natural phenomenon is now expect, weather is plant and animal extinctions. causing a range of changes throughout In order to make well-informed Earth’s system. what you get.” decisions that will enable humans and In this chapter we consider the Robert A. Heinlein other organisms to continue to thrive on differences between climate and Earth into the future, today’s students weather, look at the climate system in arth’s global climate is changing, need to have at least a basic scientific more detail, discuss what it means for bringing numerous changes to the understanding of our planet’s climate climate to change, and take a closer E planet and the organisms that live system and the role that humans are look at the Greenhouse Effect and what on it. Validated records from instruments playing in changing it. students know about this important around the world show that our global The climate system encompasses a phenomenon. temperature increased by around one complex set of processes that affect degree Celsius (almost two degrees conditions around the world. One of Our Experience Fahrenheit) during the second half of the most important features of the of Climate the 20th century. Consequences of this climate system—the Greenhouse Weather and climate are a part of observed warming include substantial Effect—is necessary for life on Earth. -

Climate-Fact-Fiction-With-Discussion.Pdf

Climate Fact: Fiction: More info: The greenhouse gas effect is The greenhouse gas effect is The natural levels of water, carbon dioxide, and other greenhouse gases in the natural and keeps the Earth caused solely by man and atmosphere cause the greenhouse effect to influence the temperatures on the earth’s from being freezing cold. detrimental to life. surface substantially. Without this natural greenhouse effect, the Earth would be much colder than it is today (~0°F), and life forms on the planet would be very different. Almost everything we do Our personal carbon footprint is Your carbon footprint – the amount of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases directly or indirectly comprised only of the carbon emitted into the atmosphere due to your activities – includes both not only what you releases greenhouse gases dioxide that you emit directly directly emit through your activities (e.g., driving a car), but also the emissions made into the environment. through activities such as during the creation, transportation, sale, and disposal of the products you purchase (e.g., driving. the emissions of the factory that created your T-shirt, the emissions from the tractor trailer that carried the T-shirt to the mall, etc.). Calculation is difficult; e.g., would you add the emissions of transporting your t-shirt to the mall to the driver’s footprint or yours? Man-made greenhouse The environment naturally The Earth’s atmosphere is like a bathtub. There is a faucet (manmade and natural gases have been and still are removes greenhouse gases from processes) putting water (greenhouse gases) into the bathtub (the atmosphere).