Revised Guidelines on the Treatment of Chechen Idps, Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crossing a Raging River on a Shaky Branch: Chechen Women Refugees in the United States

Journal of Conflict Management 2018 Volume 6, Number 1 CROSSING A RAGING RIVER ON A SHAKY BRANCH: CHECHEN WOMEN REFUGEES IN THE UNITED STATES Olya Kenney Nova Southeastern University Alexia Georgakopoulos Nova Southeastern University Abstract The Chechen War was a brutal conflict that has created, by some estimates, more than half a million refugees worldwide. An important goal in this research was to understand the life story and the lived experience of eight Chechen women refugees who survived the war in Chechnya. A descriptive phenomenological process coupled with a critical feminist approach were used in this interpretive study. The experiences of Chechen refugees, and especially Chechen women, have often been neglected in research on the war. When their experiences have been considered, Chechen women have been conceived of primarily as either helpless victims with little or no agency or as fanatical suicide bombers inspired by radical Islam, or both. Through rich descriptions, these participants unveiled the extent to which they were generative (concerned for the future and future generations). Generativity has been positively associated with well-being as well as social and political engagement. Interviewees revealed experiences of loss and anxiety during the war, and of struggling to survive. Once they arrived in the United States, participant experiences included economic hardship and cultural dislocation. Alongside these experiences, the women also experienced resistance, resilience, and generativity. The following nine major themes emerged from participants’ phenomenological life stories: Losses, War Trauma, Resistance, and Resilience, Struggling to Create a New Life, Faith, Gender, Ethnicity, and Generativity. Analysis of the narratives revealed similarities between Generativity and the themes of Faith and Ethnicity. -

List of Acronyms

List of Acronyms ADB Asian Development Bank DAFI Albert Einstein Academic Scholarship Programme for Refugees AfDB African Development Bank DPA United Nations Department of Political ALAC Advice and Legal Aid Centre Affairs ART Anti-retroviral therapy DPKO United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations DRC Danish Refugee Council AU African Union DRC The Democratic Republic of the Congo AU/PSC African Union Peace and Security Council EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development CA Consolidated Appeal EC European Commission CAP Consolidated Appeals Process (Inter-agency) ECA Economic Commission for Africa (UN) CBCP The Söderköping/Cross Border ECHA Executive Committee on Humanitarian Cooperation Process Affairs (United Nations) CBSA Canada Border Services Agency ECHO European Commission Humanitarian Office CCA Common Country Assessment (UN) ECOSOC Economic and Social Council (United CCCM Camp coordination and camp Nations) management (cluster) ECOWAS Economic Community of West Africa CEDAW Committee on the Elimination of All States Forms of Discrimination Against Women ECRE European Council on Refugees and CEB Council of Europe Development Bank Exiles CERF Central Emergency Response Fund EDF European Development Fund (formerly Central Emergency Revolving Fund) ELENA European Legal Network on Asylum CHAP Common Humanitarian Action Plan EPRS Emergency Preparedness and Response CIC Citizenship and Immigration Canada Section (UNHCR) CoE Council of Europe ERC Emergency Relief Coordinator -

Kadyrovism: Hardline Islam As a Tool of the Kremlin?

Notes de l’Ifri Russie.Nei.Visions 99 Kadyrovism: Hardline Islam as a Tool of the Kremlin? Marlène LARUELLE March 2017 Russia/NIS Center The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental, non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the few French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European and broader international debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. This text is published with the support of DGRIS (Directorate General for International Relations and Strategy) under “Observatoire Russie, Europe orientale et Caucase”. ISBN: 978-2-36567-681-6 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2017 How to quote this document: Marlène Laruelle, “Kadyrovism: Hardline Islam as a Tool of the Kremlin?”, Russie.Nei.Visions, No. 99, Ifri, March 2017. Ifri 27 rue de la Procession 75740 Paris Cedex 15—FRANCE Tel.: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00—Fax : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Email: [email protected] Ifri-Bruxelles Rue Marie-Thérèse, 21 1000—Brussels—BELGIUM Tel.: +32 (0)2 238 51 10—Fax: +32 (0)2 238 51 15 Email: [email protected] Website: Ifri.org Russie.Nei.Visions Russie.Nei.Visions is an online collection dedicated to Russia and the other new independent states (Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan). -

Russia's Islamic Diplom

Russia's Islamic Diplom Russia's Islamic Diplomacy ed. Marlene Laruelle CAP paper no. 220, June 2019 "Islam in Russia, Russia in the Islamic World" Initiative Russia’s Islamic Diplomacy Ed. Marlene Laruelle The Initiative “Islam in Russia, Russia in the Islamic World” is generously funded by the Henry Luce Foundation Cover photo: Talgat Tadjuddin, Chief Mufti of Russia and head of the Central Muslim Spiritual Board of Russia, meeting with the Armenian Catholicos Karekin II and Mufti Ismail Berdiyev, President of the Karachay-Cherkessia Spiritual Board, Moscow, December 1, 2016. Credit : Artyom Korotayev, TASS/Alamy Live News HAGFW9. Table of Contents Chapter 1. Russia and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation: Conflicting Interactions Grigory Kosach………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Chapter 2. Always Looming: The Russian Muslim Factor in Moscow's Relations with Gulf Arab States Mark N. Katz………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 1 Chapter 3. Russia and the Islamic Worlds: The Case of Shia Islam Clément Therme ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 25 Chapter 4. A Kadyrovization of Russian Foreign Policy in the Middle East: Autocrats in Track II Diplomacy and Other Humanitarian Activities Jean-Francois Ratelle……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 1 Chapter 5. Tatarstan's Paradiplomacy with the Islamic World Guzel Yusupova……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 7 Chapter 6. Russian Islamic Religious Authorities and Their Activities at the Regional, National, and International Levels Denis Sokolov………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 41 Chapter 7. The Economics of the Hajj: The Case of Tatarstan Azat Akhunov…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 7 Chapter 8. The Effect of the Pilgrimage to Mecca on the Socio-Political Views of Muslims in Russia’s North Caucasus Mikhail Alexseev…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 3 Authors’ Biographies……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 9 @ 2019 Central Asia Program Chapter 1. -

Chechnya's Status Within the Russian

SWP Research Paper Uwe Halbach Chechnya’s Status within the Russian Federation Ramzan Kadyrov’s Private State and Vladimir Putin’s Federal “Power Vertical” Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs SWP Research Paper 2 May 2018 In the run-up to the Russian presidential elections on 18 March 2018, the Kremlin further tightened the federal “vertical of power” that Vladimir Putin has developed since 2000. In the North Caucasus, this above all concerns the republic of Dagestan. Moscow intervened with a powerful purge, replacing the entire political leadership. The situation in Chechnya, which has been ruled by Ramzan Kadyrov since 2007, is conspicuously different. From the early 2000s onwards, President Putin conducted a policy of “Chechenisation” there, delegating the fight against the armed revolt to local security forces. Under Putin’s protection, the republic gained a leadership which is now publicly referred to by Russians as the “Chechen Khanate”, among other similar expressions. Kadyrov’s breadth of power encompasses an independ- ent foreign policy, which is primarily orientated towards the Middle East. Kadyrov emphatically professes that his republic is part of Russia and presents himself as “Putin’s foot soldier”. Yet he has also transformed the federal subject of Chechnya into a private state. The ambiguous relationship between this republic and the central power fundamentally rests on the loyalty pact between Putin and Kadyrov. However, criticism of this arrange- ment can now occasionally be heard even in the Russian president’s inner circles. With regard to Putin’s fourth term, the question arises just how long the pact will last. -

The War in Chechnya and Its Aftermath

Baylis, Wirtz & Gray: Strategy in the Contemporary World 6e Holding a Decaying Empire Together: The War in Chechnya and its Aftermath On 25 December 1991, the Soviet Union officially was dissolved, with the former superpower splitting into 15 individual states. Each of these entities had been a constituent ‘republic’ of the USSR built around one of the major ethnicities within the country—Russia itself was dominated by Russians, Ukraine by Ukrainians, and so forth. The 15 republics, however, actually greatly simplified the diversity of the Soviet state, which contained hundreds of distinct ethnic groups, many of which dominated a small piece of territory within a republic. In many cases, these groups had certain limited rights to govern themselves locally and independently of the larger republic of which they were a part. The Chechens were one such group. Chechnya is located in Russia, in the mountainous Caucasus and bordering the now-independent country of Georgia. The total number of Chechens is small, although exact numbers are disputed—there are perhaps somewhat over two million Chechens, many of whom live outside Chechnya itself; the population of Chechnya itself is approximately 1.2 million, but this includes Ingush, Kumyks, Russians, and other non-Chechens. The great majority of Chechens are Muslims, and although Chechnya was incorporated into the Russian Empire in the nineteenth century (and Russia had influence in the region much earlier), their culture remains quite distinct from that of the Russians. During the Soviet period, Chechens were joined with another small Caucasian Muslim group, the Ingush, in a local governing entity. -

Syria: Internally Displaced Persons, Returnees and Internal Mobility — 3

European Asylum Support Office Syria Internally displaced persons, returnees and internal mobility Country of Origin Information Report April 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Syria Internally displaced persons, returnees and internal mobility Country of Origin Information Report April 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-158-1 doi: 10.2847/460038 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © DFID - UK Department for International Development, Syrian women and girls in an informal tented settlement in the Bekaa Valley, Lebanon, 3 February 2017, (CC BY 2.0) https://www.flickr.com/photos/dfid/31874898573 EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN REPORT SYRIA: INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS, RETURNEES AND INTERNAL MOBILITY — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge Sweden, Swedish Migration Agency, Country of Origin Information, Section for Information Analysis, as the drafter of this report. The following departments and organisations have reviewed the report: Denmark, Danish Immigration Service (DIS) ACCORD, the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. 4 — EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN REPORT SYRIA: INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS, RETURNEES AND INTERNAL MOBILITY Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ -

Georgia's Pankisi Gorge

CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN POLICY STUDIES CEPS POLICY BRIEF NO. 23 JUNE 2002 GEORGIA’S PANKISI GORGE RUSSIAN, US AND EUROPEAN CONNECTIONS JABA DEVDARIANI AND BLANKA HANCILOVA CEPS Policy Briefs are published to provide concise, policy-oriented analysis of contemporary issues in EU affairs. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed are attributable to only the authors and not to any institution with which they are associated. Available for free downloading from the CEPS website (http://www.ceps.be) © Copyright 2002, Jaba Devdariani and Blanka Hancilova G EORGIA’S P ANKISI G ORGE: R USSIAN, US AND E UROPEAN C ONNECTIONS CEPS POLICY BRIEF NO. 23 1 JABA DEVDARIANI AND BLANKA HANCILOVA The Georgian government fails to exercise effective control over parts of its territory. In the last decade, Georgian statehood has been threatened by a civil war and secessionist conflicts. Its government has failed to reform its armed forces and has lost control over the Pankisi Gorge, a sparsely populated patch of the Caucasus Mountains on the border to Chechnya. Some hundreds Chechen fighters including several dozen Islamic extremists connected to the al-Qaeda network are believed to be hiding in that area. After the attacks on the United States on 11 September, the risks posed by failing states in the propagation of international terrorist networks are being taken more seriously into consideration. 2 The US decision to send up to 200 special operation forces to Georgia in March 2002, in order to train Georgian forces to regain control over the Pankisi Gorge, proceeds from this logic. The European Union and its member states are fully engaged in the American-led campaign against international terrorism. -

a Guide on How to Start an Entrepreneurial Project and Come from Idea to Action

- a guide on how to start an entrepreneurial project and come from idea to action was a three-year project about entrepreneurship for young people with refugee backgrounds. The project was implemented and developed in a partnership between DRC Danish Refugee Coun- cil and Foreningen Roskilde Festival between 2018 and 2020. Contents The project consisted of professional workshops on entrepreneurship, mentorships by voluntary business professionals for all the participants, and the building of partnerships between other organizations and municipalities. Results CO:LAB was a big success, and overall 36 entrepreneurs with refugee backgrounds completed the project. Of these, 23 succeeded in starting their own business because of the aid they received from the CO:LAB project. 65% succeeded in starting their own business, and 95% were in jobs or taking an education at the end of the project. You can read more about how you can succeed in helping refugees and others into becoming entrepreneurs in this e-book. INDHOLDSFORTEGNELSE I n t r o d u c t I o n t o t h e e-BOOK ........................................... 3 h o w t o g e t s ta r t e d ........................................................... 4 th e p u r p o s e o f a n entrepreneur I a l p r oj e c t ..................... 5 pa r t n e r s h I p s a n d c o l l a B o r at I o n ...................................... 6 a c t I v I t I e s ........................................................................... 7 r e c r u I t m e n t o f pa r t I c I pa n t s a n d v o l u n t e e r m e n t o r s ..... -

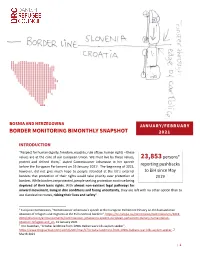

Border Monitoring Bimonthly Snapshot 2021

BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA JANUARY/FEBRUARY BORDER MONITORING BIMONTHLY SNAPSHOT 2021 INTRODUCTION “Respect for human dignity, freedom, equality, rule of law, human rights – these values are at the core of our European Union. We must live by these values, 23,853 persons* protect and defend them,” stated Commissioner Johansson in her speech reporting pushbacks before the European Parliament on 19 January 20211. The beginning of 2021, however, did not give much hope to people stranded at the EU’s external to BiH since May borders that protection of their rights would take priority over protection of 2019 borders. While borders are protected, people seeking protection continue being deprived of their basic rights. With almost non-existent legal pathways for onward movement, living in dire conditions and facing uncertainty, they are left with no other option than to use clandestine routes, risking their lives and safety2. 1 European Commission, “Commissioner Johansson's speech at the European Parliament Plenary on the humanitarian situation of refugees and migrants at the EU's external borders”, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/2019- 2024/johansson/announcements/commissioner-johanssons-speech-european-parliament-plenary-humanitarian- situation-refugees-and_en, 19 January 2021 2 The Guardian, "Croatia: landmine from 1990s Balkan wars kills asylum seeker”, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/mar/07/croatia-landmine-from-1990s-balkans-war-kills-asylum-seeker, 7 March 2021 | 1 On January 11, the Council of Europe Commissioner for -

Pankisskoye Gorge: Residents, Refugees & Fighters

Conflict Studies Research Centre P37 Pankisskoye Gorge: Residents, Refugees & Fighters C W Blandy Prospective US/Georgian action against the 'terrorists' in the Pankisskoye gorge in Georgia requires a sensitive approach. The ethnic groups long settled in the area include Chechen-Kistins, who offered shelter to Chechen refugees in the second Chechen conflict. The ineffectual Georgian government has acquiesced in previous Russian actions inside Georgia and attempts to control the border in difficult terrain. Unless Georgian actions in the gorge have Russian support, they run the risk of souring relations in the region and may not solve the local 'terrorist' problem. Contents Introduction 2 Map 1 - Georgia 3 Background - Peoples & Frontiers 3 Table 1 - Peoples in Dagestan (RF) Azerbaijan & Georgia Divided by International Frontiers 4 Map 2 - Boundaries Between Chechnya, Dagestan, Georgia & Azerbaijan 5 The Chechen-Kistin 6 Box 1 - Chechen-Kistin Background 6 Importance of Pankisi to Chechen Fighters 7 Terrain Between the Pankisskoye Gorge & Chechen Border 7 Map 3 - Pankisskoye Gorge & Omalo NE Georgia 8 Map 4 - Securing the Checheno-Georgian Border 9 The Capture of Itum-Kale 10 Box 2 - Initial Border Operations in December 1999 10 Summer-Autumn 2001 12 Peregrinations of Ruslan Gelayev 13 Map 5 - The Sukhumi Military Road & Kodori Gorge 15 Box 3 - Violations of Georgian Airspace 27-28 November 2001 16 New Operations in Pankisi? 16 A Spectrum of Views 16 Conclusion 18 Scope of Operations 18 1 Pankisskoye Gorge: Residents, Refugees & Fighters -

EU Facility for Refugees in Turkey. List of Projects Committed/Decided

Status: updated on 31/08/2021 EU Facility for Refugees in Turkey List of projects committed/decided, contracted, disbursed The EU Facility has a total budget of €6 billion for humanitarian and development actions: €3 billion for 2016-2017 and €3 billion for 2018-20191. Both tranches combined, all operational funds have been committed and contracted and close to €4.3 billion disbursed. Second tranche of €3 billion for 2018-2019 Amount Disbursements Funding Implementing Amount Committed Priority area Title & Description Contracted to projects Instrument Partner in € in € in € HIP Turkey Improving access of most vulnerable refugees to Social Services UNFPA Protection 234.322 234.322 234.322 2019 in Turkey HIP Turkey STAT - Supporting transition and access in Turkey for specialized Relief International Health 4.765.678 4.765.678 3.812.542 2019 health services HIP Turkey Access to protection and services for refugees and asylum UNHCR Protection 23.929.195 23.929.195 19.143.356 2019 seekers in Turkey HIP Turkey Deutsche Welthungerhilfe PIPS II – Provision of Integrated Protection Services in Mardin Basic Needs 2.000.000 2.000.000 1.600.000 2019 (WHH) and Diyabakir HIP Turkey Support for school enrolment for vulnerable refugee children in UNICEF Education 10.000.000 10.000.000 8.000.000 2019 Turkey International Federation of HIP Turkey the Red Cross Societies Basic Needs ESSN III - Emergency Social Safety Net 500.000.000 500.000.000 490.000.000 2019 (IFRC) HIP Turkey WFP Basic Needs ESSN II - Emergency Social Safety Net 357.800.000 354.966.886