Constraining Certiorari Using Administrative Law Principles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

No. 15-___ IN THE SEQUENOM, INC., Petitioner, v. ARIOSA DIAGNOSTICS, INC., NATERA, INC., AND DNA DIAGNOSTICS CENTER, INC. Respondents. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI Michael J. Malecek Thomas C. Goldstein Robert Barnes Counsel of Record KAYE SCHOLER LLP Eric F. Citron Two Palo Alto Square G OLDSTEIN & RUSSELL, P.C. Suite 400 7475 Wisconsin Ave. 3000 El Camino Real Suite 850 Palo Alto, CA 94306 Bethesda, MD 20814 (650) 319-4500 (202) 362-0636 [email protected] QUESTION PRESENTED In 1996, two doctors discovered cell-free fetal DNA (cffDNA) circulating in maternal plasma. They used that discovery to invent a test for detecting fetal genetic conditions in early pregnancy that avoided dangerous, invasive techniques. Their patent teaches technicians to take a maternal blood sample, keep the non-cellular portion (which was “previously discarded as medical waste”), amplify the genetic material with- in (which they alone knew about), and identify pater- nally inherited sequences as a means of distinguish- ing fetal and maternal DNA. Notably, this method does not preempt other demonstrated uses of cffDNA. The Federal Circuit “agree[d]” that this invention “combined and utilized man-made tools of biotechnol- ogy in a new way that revolutionized prenatal care.” Pet.App. 18a. But it still held that Mayo Collabora- tive Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., 132 S. Ct. 1289 (2012), makes all such inventions patent-ineligible as a matter of law if their new combination involves only a “natural phenomenon” and techniques that were “routine” or “conventional” on their own. -

Bush V. Superior Court (Rains), 10 Cal.App.4Th 1374 (1992)

Supreme Court, U.S. FILED ( p NOV 272018 1.1 No. k I \ zy OFFICE OF THE CLERK iiiii ORGNAL SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES RASH B. GHOSH and INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF BENGAL BASIN, Petitioners, V. CITY OF BERKELEY, ZACH COWAN, LAURA MCKINNEY, JOAN MACQUARRIE, PATRICK EMMONS, GREG HEIDENRICH, CARLOS ROMO, GREG DANIEL, MANAGEWEST, BENJAMIN MCGREW, KORMAN & NG, INC., MICHAEL KORMAN, MIRIAM NG, ROMAN FAN, ROBERT RICHERSON, KRISTEN DIEDRE RICHERSON, ANDREA RICHERSON, DEBRA A. RICHERSON, AND PRISM TRUST, Re s p0 ii den t S. On Petition For a Writ of Certiorari To The California Court of Appeal, First Appellate District PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI Rash B. Ghosh Pro Se P. 0. Box 11553 Berkeley, CA 94712 (510) 575-5112 THE QUESTION PRESENTED Ghosh owned two adjacent buildings in Berkeley, and the co- plaintiff, International Institute of Bengal Basin (IIBB) occupied one of them. In a pending lawsuit, petitioners filed a third amended complaint, alleging that newly discovered evidence showed that the newly-named defendants conspired with the other defendants to deprive them of their property and arrange for it to be sold at a below-market price to some of the new. defendants. The trial court sustained demurrers by the defendants, and Ghosh and IIBB sought to appeal. Because Petitioner Ghosh had been found to be a vexatious litigant, he had to make application to the presiding justice of the Court of Appeal for permission to appeal, and show that the appeal had merit. He made application, and pointed out numerous (and sometimes obvious) errors the trial court had made in sustaining the demurrer. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

6Upreme Court of ®Bio

1" tC,e 6upreme Court of ®bio IN RE: DARIAN J. SMITH, Case No. 2008-1624 A Delinquent Child. On Appeal from the Allen County Court of Appeals, Third Appellate District Court of Appeals Case No. 1-07-58 AMICUS CURIAE OHIO ATTORNEY GENERAL RICHARD CORDRAY'S NOTICE OF APPEARANCE OF ADDITIONAL COUNSEL BROOKE M. BURNS* (0080256) RICHARD CORDRAY (0038034) *Counsel ofRecord Attorney General of Ohio Assistant State Public Defender 250 E. Broad St., Suite 1400 BENJAMIN C. MIZER* (0083089) Columbus, Ohio 43215 Solicitor General 614-466-5394 *Counsel ofRecord 614-752-5167 fax ALEXANDRA T. SCHIMMER (0075732) brooke.burns@opd. ohio. gov Chief Deputy Solicitor General DAVID M. LIEBERMAN (pro hac vice) Counsel for Appellant Smith Deputy Solicitor CHRISTOPHER P. CONOMY (0072094) JUERGEN A. WALDICK (0030399) JAMES A. HOGAN (0071064) Allen County Prosecutor Assistant Attorneys General CHRISTINA L. STEFFAN* (0075206) 30 East Broad Street, 17th Floor Assistant Prosecutor Columbus, Ohio 43215 *Counsel ofRecord 614-466-8980 204 N. Main St., Suite 302 614-466-5087 fax Lima, Ohio 45801 benj amin.mizer@ohioattorneygeneral. gov 419-228-3700 419-222-2462 fax Counsel for Amicus Curiae [email protected] Ohio Attorney General Richard Cordray Counsel for Appellee State of Ohio ME OC'1' C Z ?009 CLERK OF COURT SUpREME COURT OF OHIO AMICUS CURIAE OHIO ATTORNEY GENERAL RICHARD CORDRAY'S NOTICE OF APPEARANCE OF ADDITIONAL COUNSEL Assistant Attorney General James A. Hogan enters his appearance as co-counsel for Amicus Curiae Ohio Attorney General Richard Cordray in the above captioned matter. Benjamin C. Mizer will remain as Counsel of Record in the case. -

ADMINISTRATIVE LAW PAPER CODE- 801 TOPIC- WRITS Constitutional Philosophy of Writs

CLASS- B.A.LL.B VIIIth SEMESTER SUBJECT- ADMINISTRATIVE LAW PAPER CODE- 801 TOPIC- WRITS Constitutional philosophy of Writs: A person whose right is infringed by an arbitrary administrative action may approach the Court for appropriate remedy. The Constitution of India, under Articles 32 and 226 confers writ jurisdiction on Supreme Court and High Courts, respectively for enforcement/protection of fundamental rights of an Individual. Writ is an instrument or order of the Court by which the Court (Supreme Court or High Courts) directs an Individual or official or an authority to do an act or abstain from doing an act. Understanding of Article 32 Article 32 is the right to constitutional remedies enshrined under Part III of the constitution. Right to constitutional remedies was considered as a heart and soul of the constitution by Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar. Article 32 makes the Supreme court as a protector and guarantor of the Fundamental rights. Article 32(1) states that if any fundamental rights guaranteed under Part III of the Constitution is violated by the government then the person has right to move the Supreme Court for the enforcement of his fundamental rights. Article 32(2) gives power to the Supreme court to issue writs, orders or direction. It states that the Supreme court can issue 5 types of writs habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto, and certiorari, for the enforcement of any fundamental rights given under Part III of the constitution. The Power to issue writs is the original jurisdiction of the court. Article 32(3) states that parliament by law can empower any of courts within the local jurisdiction of India to issue writs, order or directions guaranteed under Article 32(2). -

G:\OSG\Desktop

No. 08-267 In the Supreme Court of the United States UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, PETITIONER v. JACOB DENEDO ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ARMED FORCES PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI GREGORY G. GARRE Acting Solicitor General LOUIS J. PULEO Counsel of Record Col., USMC MATTHEW W. FRIEDRICH Director Acting Assistant Attorney BRIAN K. KELLER General Deputy Director MICHAEL R. DREEBEN Deputy Solicitor General TIMOTHY H. DELGADO Lt., JAGC, USN ERIC D. MILLER Navy-Marine Corps Assistant to the Solicitor Appellate Government General Division JOHN F. DE PUE Department of the Navy Attorney Washington, D.C. 20374 Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 (202) 514-2217 QUESTION PRESENTED Whether an Article I military appellate court has ju- risdiction to entertain a petition for a writ of error co- ram nobis filed by a former service member to review a court-martial conviction that has become final under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, 10 U.S.C. 801 et seq. (I) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Opinions below........................................ 1 Jurisdiction........................................... 1 Statutes involved...................................... 2 Statement............................................ 2 Reasons for granting the petition........................ 8 A. Collateral review of a final court-martial judgment is not “in aid of” the jurisdiction of a military appellate court.................................. 10 B. Coram nobis review is neither necessary nor appropriate in light of the alternative remedies available to former members of the armed forces.... 17 C. The question presented is important and warrants this Court’s review .............................. 21 Conclusion .......................................... 25 Appendix A — Court of appeals opinion (Mar. -

Exhaustion of State Remedies Before Bringing Federal Habeas Corpus: a Reappraisal of U.S. Code Section

Nebraska Law Review Volume 43 | Issue 1 Article 7 1963 Exhaustion of State Remedies before Bringing Federal Habeas Corpus: A Reappraisal of U.S. Code Section Merritt aJ mes University of Nebraska College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation Merritt aJ mes, Exhaustion of State Remedies before Bringing Federal Habeas Corpus: A Reappraisal of U.S. Code Section, 43 Neb. L. Rev. 120 (1964) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol43/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. NEBRASKA LAW REVIEW VOL. 43, NO. 1 EXHAUSTION OF STATE REMEDIES BEFORE BRINGING FEDERAL HABEAS CORPUS: A REAPPRAISAL OF U.S. CODE SECTION 2254 I. INTRODUCTION There are many instances in which a state's prisoner, after being denied his liberty for years, has subsequently, upon issuance of federal writ of habeas corpus, either been proven innocent or adjudged entitled to a new trial upon grounds that he was denied some constitutional right during the process of his state court trial.' In some of these cases it has been clear from the very beginning that if the allegations of the writ were proven, the de- tention was unconstitutional. Yet the prisoner is still forced to endure years of confinement while exhausting state remedies before 2 federal habeas corpus is available to him. -

Concurring in the Dismissal of the Petition

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS NO. 20-0430 IN RE STEVEN HOTZE, MD, HON. WILLIAM ZEDLER, HON. KYLE BIEDERMANN, EDD HENDEE, AL HARTMAN, NORMAN ADAMS, GABRIELLE ELLISON, TONIA ALLEN, PASTOR JOHN GREINER, AND PASTOR MATT WOODFILL, RELATORS, ON EMERGENCY PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDAMUS JUSTICE DEVINE, concurring in the petition’s dismissal for want of jurisdiction. The Texas Constitution is not a document of convenient consultation. It is a steadfast, uninterrupted charter of governmental structure. Once this structure erodes, so does the promise of liberty. In these most atypical times, Texans’ constitutional rights have taken a back seat to a series of executive orders attempting to unilaterally quell the spread of the novel coronavirus. But at what cost? Many businesses have felt the impoverishing effects of being deemed, by executive fiat, “nonessential.” And many others—unemployed—found out quickly that economic liberty is indeed “a mere luxury to be enjoyed at the sufferance of governmental grace.”1 That can’t be right. While we entrust our health and safety to politically accountable officials,2 we must not do so at the expense of basic constitutional architecture. We should not, as we’ve recently said, 1 Patel v. Tex. Dep’t of Licensing & Regulation, 469 S.W.3d 69, 92 (Tex. 2014) (Willett, J., concurring). 2 See S. Bay United Pentecostal Church v. Newsom, No. 19A1044, 2020 U.S. LEXIS 3041, at *3 (U.S. May 29, 2020) (mem.) (Roberts, C.J., concurring in the denial of injunctive relief) (citing Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11, 38 (1905)). “abandon the Constitution at the moment we need it most.”3 I concur in the dismissal of this mandamus petition for want of jurisdiction, but I write separately to express concern over some of the issues it raises. -

20210716182833230 2021.0716 OABA Petition for Certiorari.Pdf

NO. _______________ SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES _______________ OUTDOOR AMUSEMENT BUSINESS ASSOCIATION, INC.; MARYLAND STATE SHOWMEN'S ASSOCIATION, INC.; THE SMALL AND SEASONAL BUSINESS LEGAL CENTER; LASTING IMPRESSIONS LANDSCAPE CONTRACTORS, INC.; THREE SEASONS LANDSCAPE CONTRACTING SERVICES, INC.; NEW CASTLE LAWN & LANDSCAPE, INC., Petitioners v. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY; UNITED STATES CITIZENSHIP & IMMIGRATION SERVICES; DEPARTMENT OF LABOR; EMPLOYMENT & TRAINING ADMINISTRATION; WAGE & HOUR DIVISION, Respondents _______________ On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court Of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit _______________ PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI _______________ R. Wayne Pierce, Esq. Leon R. Sequeira, Esq. The Pierce Law Firm, LLC Counsel of Record 133 Defense Hwy, Suite 201 616 South Adams Street Annapolis, Maryland 21401 Arlington, Virginia 22204 410-573-9955 (202) 255-9023 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Petitioners QUESTION PRESENTED With exceptions not relevant hereto, Congress has expressly bestowed all "administration and enforcement" functions under the Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. §§1101 et seq., including rulemaking and adjudication for the admission of temporary, non-agricultural workers under the H-2B visa program, exclusively on the Secretary of Homeland Security. Id. §§ 1101(a)(15)(H)(ii)(b), 1103(a)(1), (3), and 1184(a)(1), (c)(1). The Secretary adjudicates employer H-2B petitions "after consultation with appropriate agencies of the Government." Id. § 1184(c)(1). The question presented is: Whether Congress, consistent with the nondelegation doctrine and clear-statement rule, impliedly authorized the Secretary of Labor individually to promulgate legislative rules for the admission of H-2B workers and adjudicate H-2B labor certifications. -

Between the Courts and Congress Is the Future of the CFPB in Jeopardy?

Between the Courts and Congress Is the Future of the CFPB in Jeopardy? Throughout the nearly six years of its existence, the The underlying dispute first arose in 2015, which resulted in a CFPB administrative law judge’s recommendation of a US$6.5 Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB or the million fine against PHH for allegedly requiring unlawful kickbacks from mortgage insurers in violation of Section 8 of the Real Estate “Bureau”) has been the target of attacks in various Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA). PHH appealed that decision to courtrooms and the halls of Congress. No doubt the CFPB Director Richard Cordray, who rejected its arguments and then increased the fine to US$109 million. previous administration and the then Democrat- On October 11, 2016, the DC Circuit vacated the US$109 million controlled Congress designed the CFPB to withstand enforcement order by the CFPB, finding that not only was its interpretation of RESPA unreasonable, but that the CFPB’s structure political winds (i.e., an independent agency not is too unaccountable to be constitutional and poses an opportunity subject to congressional appropriations and headed for the Director to abuse his power. To remedy this potential for abuse of power, the Court ordered that the CFPB would no longer by a single director appointed by the President, be an “independent” agency, but “now will operate as an executive removable only for cause). agency” and that President Trump “now has the power to supervise and direct the Director of the CFPB, and may remove the Director at At this point, however, President Trump, the Republican-controlled will at any time.” This decision has been stayed pending the results House and Senate and the courts are about to test its durability. -

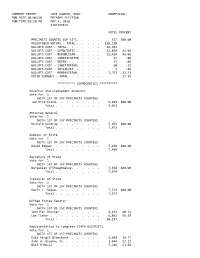

Summary Report Lake County, Ohio Unofficial Run Date:05/04/10 Primary Election Run Time:10:20 Pm May 4, 2010 Statistics

SUMMARY REPORT LAKE COUNTY, OHIO UNOFFICIAL RUN DATE:05/04/10 PRIMARY ELECTION RUN TIME:10:20 PM MAY 4, 2010 STATISTICS VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 157). 157 100.00 REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 156,210 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 26,952 BALLOTS CAST - DEMOCRATIC . 11,058 41.03 BALLOTS CAST - REPUBLICAN . 12,414 46.06 BALLOTS CAST - CONSTITUTION . 17 .06 BALLOTS CAST - GREEN. 23 .09 BALLOTS CAST - LIBERTARIAN. 60 .22 BALLOTS CAST - SOCIALIST . 7 .03 BALLOTS CAST - NONPARTISAN. 3,373 12.51 VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 17.25 ********** (DEMOCRATIC) ********** Governor and Lieutenant Governor Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Ted Strickland. 9,021 100.00 Total . 9,021 Attorney General Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Richard Cordray . 7,973 100.00 Total . 7,973 Auditor of State Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) David Pepper . 7,430 100.00 Total . 7,430 Secretary of State Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Maryellen O'Shaughnessy. 7,874 100.00 Total . 7,874 Treasurer of State Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Kevin L. Boyce. 7,572 100.00 Total . 7,572 United States Senator Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Jennifer Brunner . 4,135 40.71 Lee Fisher . 6,022 59.29 Total . 10,157 Representative to Congress (14TH DISTRICT) Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Dale Virgil Blanchard . 1,658 19.77 John H. Greene, Jr. 1,444 17.22 Bill O'Neill . 5,286 63.02 Total . 8,388 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Vote for 1 (WITH 157 OF 157 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Eric Brown . -

15. Judicial Review

15. Judicial Review Contents Summary 413 A common law principle 414 Judicial review in Australia 416 Protections from statutory encroachment 417 Australian Constitution 417 Principle of legality 420 International law 422 Bills of rights 422 Justifications for limits on judicial review 422 Laws that restrict access to the courts 423 Migration Act 1958 (Cth) 423 General corporate regulation 426 Taxation 427 Other issues 427 Conclusion 428 Summary 15.1 Access to the courts to challenge administrative action is an important common law right. Judicial review of administrative action is about setting the boundaries of government power.1 It is about ensuring government officials obey the law and act within their prescribed powers.2 15.2 This chapter discusses access to the courts to challenge administrative action or decision making.3 It is about judicial review, rather than merits review by administrators or tribunals. It does not focus on judicial review of primary legislation 1 ‘The position and constitution of the judicature could not be considered accidental to the institution of federalism: for upon the judicature rested the ultimate responsibility for the maintenance and enforcement of the boundaries within which government power might be exercised and upon that the whole system was constructed’: R v Kirby; Ex parte Boilermakers’ Society of Australia (1956) 94 CLR 254, 276 (Dixon CJ, McTiernan, Fullagar and Kitto JJ). 2 ‘The reservation to this Court by the Constitution of the jurisdiction in all matters in which the named constitutional writs or an injunction are sought against an officer of the Commonwealth is a means of assuring to all people affected that officers of the Commonwealth obey the law and neither exceed nor neglect any jurisdiction which the law confers on them’: Plaintiff S157/2002 v Commonwealth (2003) 211 CLR 476, [104] (Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ).