Comparing Global Gender Inequality Indices: What Can They Tell Us About Development?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bosnia and Herzegovina and the United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework

Bosnia and Herzegovina and the United Nations 2021- Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework 2025 A Partnership for Sustainable Development Declaration of commitment The authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) and the United Nations (UN) are committed to working together to achieve priorities in BiH. These are expressed by: ` The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and selected Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and targets1 as expressed in the emerging SDG Framework in BiH and domesticated SDG targets2; ` Future accession to the European Union, as expressed in the Action Plan for implementation of priorities from the European Commission Opinion and Analytical Report3; ` The Joint Socio-Economic Reforms (‘Reform Agenda’), 2019-20224; and ` The human rights commitments of BiH and other agreed international and regional development goals and treaty obligations5 and conventions. This Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (CF), adopted by the BiH Council of Ministers at its 22nd Session on 16 December 2020 and reconfrmed by the BiH Presidency at its 114th Extraordinary Session on 5 March 2021, will guide the work of authorities in BiH and the UN system until 2025. This framework builds on the successes of our past cooperation and it represents a joint commitment to work in close partnership for results as defned in this Cooperation Framework that will help all people in BiH to live longer, healthier and more prosperous and secure lives. In signing hereafter, the cooperating partners endorse this Cooperation Framework and underscore their joint commitments toward the achievement of its results. Council of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina United Nations Country Team H.E. Dr. Zoran Tegeltija Dr. -

Central African Republic

Human Development Report 2014 Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience Explanatory note on the 2014 Human Development Report composite indices Central African Republic HDI values and rank changes in the 2014 Human Development Report Introduction The 2014 Human Development Report (HDR) presents the 2014 Human Development Index (HDI) (values and ranks) for 187 countries and UN-recognized territories, along with the Inequality-adjusted HDI for 145 countries, the Gender Development Index for 148 countries, the Gender Inequality Index for 149 countries, and the Multidimensional Poverty Index for 91 countries. Country rankings and values of the annual Human Development Index (HDI) are kept under strict embargo until the global launch and worldwide electronic release of the Human Development Report. It is misleading to compare values and rankings with those of previously published reports, because of revisions and updates of the underlying data and adjustments to goalposts. Readers are advised to assess progress in HDI values by referring to table 2 (‘Human Development Index Trends’) in the Statistical Annex of the report. Table 2 is based on consistent indicators, methodology and time-series data and thus shows real changes in values and ranks over time, reflecting the actual progress countries have made. Small changes in values should be interpreted with caution as they may not be statistically significant due to sampling variation. Generally speaking, changes at the level of the third decimal place in any of the composite indices are considered insignificant. Unless otherwise specified in the source, tables use data available to the HDRO as of 15 November 2013. -

Faqs) About the Gender Inequality Index (GII

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Gender Inequality Index (GII) What is the Gender Inequality Index? The Gender Inequality Index is a composite measure reflecting inequality in achievements between women and men in three dimensions: reproductive health, empowerment and the labour market. It varies between zero (when women and men fare equally) and one (when men or women fare poorly compared to the other in all dimensions). The health dimension is measured by two indicators: maternal mortality ratio and the adolescent fertility rate. The empowerment dimension is also measured by two indicators: the share of parliamentary seats held by each sex and by secondary and higher education attainment levels. The labour dimension is measured by women’s participation in the work force. The Gender Inequality Index is designed to reveal the extent to which national achievements in these aspects of human development are eroded by gender inequality, and to provide empirical foundations for policy analysis and advocacy efforts. How is the GII calculated, and what are its main findings in terms of national and regional patterns of inequality? There is no country with perfect gender equality – hence all countries suffer some loss in their HDI achievement when gender inequality is taken into account, through use of the GII metric. The Gender Inequality Index is similar in method to the Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) – see Technical Note 3 for details. It can be interpreted as a percentage loss to potential human development due to shortfalls in the dimensions included. Since the Gender Inequality Index includes different dimensions than the HDI, it cannot be interpreted as a loss in HDI itself. -

Human Development Index (HDI)

Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene Briefing note for countries on the 2020 Human Development Report Chile Introduction This year marks the 30th Anniversary of the first Human Development Report and of the introduction of the Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI was published to steer discussions about development progress away from GPD towards a measure that genuinely “counts” for people’s lives. Introduced by the Human Development Report Office (HDRO) thirty years ago to provide a simple measure of human progress – built around people’s freedoms to live the lives they want to - the HDI has gained popularity with its simple yet comprehensive formula that assesses a population’s average longevity, education, and income. Over the years, however, there has been a growing interest in providing a more comprehensive set of measurements that capture other critical dimensions of human development. To respond to this call, new measures of aspects of human development were introduced to complement the HDI and capture some of the “missing dimensions” of development such as poverty, inequality and gender gaps. Since 2010, HDRO has published the Inequality-adjusted HDI, which adjusts a nation’s HDI value for inequality within each of its components (life expectancy, education and income) and the Multidimensional Poverty Index that measures people’s deprivations directly. Similarly, HDRO’s efforts to measure gender inequalities began in the 1995 Human Development Report on gender, and recent reports have included two indices on gender, one accounting for differences between men and women in the HDI dimensions, the other a composite of inequalities in empowerment and well-being. -

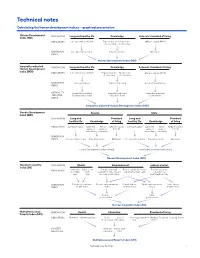

Technical Notes

Technical notes Calculating the human development indices—graphical presentation Human Development DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Index (HDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy index Education index GNI index INDEX Human Development Index (HDI) Inequality-adjusted DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Human Development Index (IHDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy Years of schooling Income/consumption INDEX INEQUALITY- Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted ADJUSTED life expectancy index education index income index INDEX Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) Gender Development Female Male Index (GDI) DIMENSIONS Long and Standard Long and Standard healthy life Knowledge of living healthy life Knowledge of living INDICATORS Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita years of years of (PPP $) years of years of (PPP $) schooling schooling schooling schooling DIMENSION INDEX Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Human Development Index (female) Human Development Index (male) Gender Development Index (GDI) Gender Inequality DIMENSIONS Health Empowerment Labour market Index (GII) INDICATORS Maternal Adolescent Female and male Female -

Inequalities in Human Development in the 21St Century

Human Development Report 2019 Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st Century Briefing note for countries on the 2019 Human Development Report Egypt Introduction The main premise of the human development approach is that expanding peoples’ freedoms is both the main aim of, and the principal means for sustainable development. If inequalities in human development persist and grow, the aspirations of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development will remain unfulfilled. But there are no pre-ordained paths. Gaps are narrowing in key dimensions of human development, while others are only now emerging. Policy choices determine inequality outcomes – as they do the evolution and impact of climate change or the direction of technology, both of which will shape inequalities over the next few decades. The future of inequalities in human development in the 21st century is, thus, in our hands. But we cannot be complacent. The climate crisis shows that the price of inaction compounds over time as it feeds further inequality, which, in turn, makes action more difficult. We are approaching a precipice beyond which it will be difficult to recover. While we do have a choice, we must exercise it now. Inequalities in human development hurt societies and weaken social cohesion and people’s trust in government, institutions and each other. They hurt economies, wastefully preventing people from reaching their full potential at work and in life. They make it harder for political decisions to reflect the aspirations of the whole society and to protect our planet, as the few pulling ahead flex their power to shape decisions primarily in their interests. -

Comparing Global Gender Inequality Indices: Where Is Trade?

DECEMB ER 2019 UNCTAD Research Paper No. 39 UNCTAD/SER.RP/2019/11 Nour Barnat Division on Comparing Global Gender Globalization and Development Strategies, UNCTAD Inequality Indices: Where is [email protected] Trade? Steve MacFeely Abstract Division on Globalization and This paper presents a comparative study of selected global Development gender inequality indices: The Global Gender Gap Index (GGI); Strategies, UNCTAD the Gender Inequality Index (GII); and the Social Institutions and [email protected] Gender Index (SIGI). A Principal Component Analysis approach is used to identify the most important factors or dimensions, such as, health, social conditions and education, economic and Anu Peltola labour participation and political empowerment that impact on gender and drive gender inequality. These factors are Division on Globalization and compared with the Sustainable Development Goal targets to Development assess how well they align. The findings show that while Strategies, UNCTAD economic participation and empowerment are significant [email protected] factors of gender equality, they are not fully incorporated into gender equality indices. In this context, the paper also discusses the absence of international trade, a key driver of economic development, from the gender equality measures and makes some tentative recommendations for how this lacuna might be addressed. Key words: Principal Component Analysis, Composite Indicators, 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, SDGs, Trade. © 2019 United Nations 2 UNCTAD Research Paper -

Gender Inequality Index and Related Indicators

TABLE 4 Gender Inequality Index and related indicators Population REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH with at least secondary Contraceptive prevalence Births Gender education Labour force participation rate rate, any At least attended Inequality Seats in (% ages 25 method one by skilled Index and older) (%) Maternal national (% of married antenatal health Total mortality Adolescent parliament women ages visit personnel fertility HDI rank Rank Value ratio fertility rate (% female) Female Male Female Male 15–49) (%) (%) rate 2011 2011 2008 2011a 2011 2010 2010 2009 2009 2005–2009b 2005–2009b 2005–2009b 2011a VERY HIGH HUMAN DEVELOPMENT 1 Norway 6 0.075 7 9.0 39.6 99.3 99.1 63.0 71.0 88.0 .. .. 2.0 2 Australia 18 0.136 8 16.5 28.3 95.1 97.2 58.4 72.2 71.0 100.0 100.0 2.0 3 Netherlands 2 0.052 9 5.1 37.8 86.3 89.2 59.5 72.9 69.0 .. 100.0 1.8 4 United States 47 0.299 24 41.2 16.8 c 95.3 94.5 58.4 71.9 73.0 .. 99.0 2.1 5 New Zealand 32 0.195 14 30.9 33.6 71.6 73.5 61.8 75.7 75.0 95.0 100.0 2.1 6 Canada 20 0.140 12 14.0 24.9 92.3 92.7 62.7 73.0 74.0 .. 98.0 1.7 7 Ireland 33 0.203 3 17.5 11.1 82.3 81.5 54.4 73.0 89.0 . -

Gender Country Profile Cyprus

Gender Country Profile Cyprus General MALES FEMALES YEAR Total population under 15 96,582 91,296 2017 Total population over 15 519,216 498,481 2017 * ALL DATA FROM CIA, 2017 Health 2015 Maternal mortality rate per 100,000 live birth 7 CIA, 2017 est. 2016 Infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births 8.1 CIA, 2017 est. Under-five mortality rate for males per 1,000 live UN Statistics, 3 2012 births 2015 Under-five mortality rate for females per 1,000 UN Statistics, 3.3 2012 live births 2015 Births attended by a skilled health professional 97 2014 WHO, 2016 Prevalence of HIV among adults aged 15–49 No Data 2015 WHO, 2017 2016 Life expectancy for men 75.8 CIA, 2017 est. 2016 Life expectancy for women 81.6 CIA, 2017 est. Education MALES FEMALES YEAR Youth literacy rate, ages 15-24 99.84% 99.88% 2015 Adult literacy rate, ages 15+ 99.46% 98.64% 2015 Net enrolment rate in primary education 97.08% 97.67% 2015 Gross enrolment ratio in secondary education 100.13% 99.41% 2015 Gross enrolment ratio in tertiary education 51.11% 69.4% 2015 * ALL DATA FROM UNESCO INSTITUTE OF STATISTICS, 2017 • Female graduates from tertiary education (2012) (UNESCO Institute of Statistics, 2015): 60.3% • Female students in engineering construction and manufacturing tertiary education programs (2012) (UNESCO Institute of Statistics, 2015): 26.5% • Female teachers in primary education (2012) (UNESCO Institute of Statistics, 2015): 82.8% June 2017 CC BY SA 1 ∣ Gender Country Profile Cyprus • Female teachers in secondary education (2012) (UNESCO Institute of Statistics, 2015): -

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Human Development Report 2014 Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience Explanatory note on the 2014 Human Development Report composite indices Saint Vincent and the Grenadines HDI values and rank changes in the 2014 Human Development Report Introduction The 2014 Human Development Report (HDR) presents the 2014 Human Development Index (HDI) (values and ranks) for 187 countries and UN-recognized territories, along with the Inequality-adjusted HDI for 145 countries, the Gender Development Index for 148 countries, the Gender Inequality Index for 149 countries, and the Multidimensional Poverty Index for 91 countries. Country rankings and values of the annual Human Development Index (HDI) are kept under strict embargo until the global launch and worldwide electronic release of the Human Development Report. It is misleading to compare values and rankings with those of previously published reports, because of revisions and updates of the underlying data and adjustments to goalposts. Readers are advised to assess progress in HDI values by referring to table 2 (‘Human Development Index Trends’) in the Statistical Annex of the report. Table 2 is based on consistent indicators, methodology and time-series data and thus shows real changes in values and ranks over time, reflecting the actual progress countries have made. Small changes in values should be interpreted with caution as they may not be statistically significant due to sampling variation. Generally speaking, changes at the level of the third decimal place in any of the composite indices are considered insignificant. Unless otherwise specified in the source, tables use data available to the HDRO as of 15 November 2013. -

Country Gender Analysis-Egypt June 2014

Country Gender Analysis Egypt June 2014 Country Gender Analysis-Egypt June 2014 Content 1. List of Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………………………….....3 2. Objective ............................................................................................................... 4 3. General Information .............................................................................................. 4 3.1 FRAMEWORK CONDITIONS ................................................................................... 4 3.2 TRADITIONAL UNDERSTANDING OF GENDER ROLES ....................................... 6 3.3 GENDER IN POLITICS ............................................................................................ 7 3.4 GENDER EQUALITY AT THE LEVEL OF THE FAMILY ........................................ 13 3.5 GENDER IN EDUCATION AND THE ECONOMY .................................................. 20 4. Resources ........................................................................................................... 29 Page 2 of 32 Country Gender Analysis-Egypt June 2014 1. List of Abbreviations CAPMAS Central Authority for Public Mobilization and Statistics CESR Center for Economic and Social Rights ECESR Egyptian Center for Economic and Social Rights ECWR Egyptian Center for Women's Rights (E)DHS (Egypt) Demographic Health Survey ETF European Training Foundation FGM Female Genital Mutilation FIDH International Federation for Human Rights GEDI Gender Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index GET Global Employment Trends GGG Global Gender -

Fig. 5.2.5 Gender Inequality Index*, G8 and Selected Countries, 2011

The Health of Canada’s Children and Youth: A CICH Profile Contextual Module Section 5 - International Comparisons 5.2.5 Gender Inequities Fig. 5.2.5 Gender Inequality Index*, G8† and selected countries, 2011 Norway 0.075 Germany 0.085 G8 Countries France 0.106 Non-G8 Countries Japan 0.123 Italy 0.124 CANADA 0.14 United Kingdom Country 0.209 China 0.209 United States 0.299 Russia 0.338 Brazil 0.449 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 Gender Inequality Index *The Gender Inequality Index, which ranges from 0 to 1, is a composite measure of inequality in achievements between women and men in three dimensions: reproductive health, empowerment, and the labour market.A Gender Inequality value of 0 indicates perfect equality between the sexes; a value of 1 indicates the worst inequality in all three areas. †G8 (Group of Eight) refers to the forum of governmental leaders of eight large, industrialized nations: the United States, Japan, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Canada, and Russia. UNDP Human Development Reports.Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/gii/. Accessed on June 29, 2012. Among the G8 countries, Canada has a lower Gender Inequality Index value than the United States, Russia, and the United Kingdom but higher than Germany, Japan, France, and Italy. For 2011, Canada ranks favourably on a worldwide basis. For 2011, some countries had values above 0.6, such as Afghanistan with a value of 0.707 and the Congo at 0.710. Canada ranked 19th out of 146 countries for which there are values for 2011.