Man:Hat Libretto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

97-Year-Old Resident Has Been Playing the Harmonica for 86 Years | Jackson News - - Mlive.Com 11/25/09 9:05 AM

97-year-old resident has been playing the harmonica for 86 years | Jackson News - - MLive.com 11/25/09 9:05 AM Brought to you by: Sign in to MLive.com » Site Search Search Local Business Listings Not a member? Register Now » Search by keyword, town name, Web ID and more... Home News Business Sports Entertainment Living Interact Jobs Autos Real Estate Classifieds Shop Place An Ad News Michigan News Opinion Obituaries Crime Education Lottery Weather See another view of this page by choosing local coverage below. How to set your local coverage Jackson Ann Arbor Bay City Detroit Flint Grand Rapids Kalamazoo Muskegon Saginaw Statewide JACKSON NEWS JACKSON WEATHER The Latest Community, Education & Government News, Blogs, Photos & Videos Jackson, MI change location 47° Cloudy JACKSON NEWS 97-year-old resident has been playing the • Other Cities, Radar, More ... Resources harmonica for 86 years • RSS | Newsletters By Jackson Citizen Patriot staff • Follow on Twitter November 24, 2009, 6:35PM • Facebook us! Forms • Engagement | Wedding • Commitment Ceremony • Anniversary • Religious Ceremony • Honors and Birthdays • Graduation Contacts • Jackson Citizen Patriot • MLive.com Jackson News headlines Related • Building damaged in S. Jackson Street blaze was uninsured; Studio of Jackson • Jackson Jobs artist destroyed in blaze 9:26 PM • Jackson Real Estate Katie Rausch | Jackson Citizen Patriot • Police focusing on drunken drivers in • Jackson Autos Jackson during holidays 11:38 PM Orville Emerson, 97, has been playing the harmonica for most of his life. Currently, • Jackson Classifieds he plays with the Rose City Harmonica Club. • Three people injured in crash on Airport Road in Jackson County 10:45 PM • Daybook for Nov. -

Karaoke Version Song Book

Karaoke Version Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Hed) Planet Earth 50 Cent Blackout KVD-29484 In Da Club KVD-12410 Other Side KVD-29955 A Fine Frenzy £1 Fish Man Almost Lover KVD-19809 One Pound Fish KVD-42513 Ashes And Wine KVD-44399 10000 Maniacs Near To You KVD-38544 Because The Night KVD-11395 A$AP Rocky & Skrillex & Birdy Nam Nam (Duet) 10CC Wild For The Night (Explicit) KVD-43188 I'm Not In Love KVD-13798 Wild For The Night (Explicit) (R) KVD-43188 Things We Do For Love KVD-31793 AaRON 1930s Standards U-Turn (Lili) KVD-13097 Santa Claus Is Coming To Town KVD-41041 Aaron Goodvin 1940s Standards Lonely Drum KVD-53640 I'll Be Home For Christmas KVD-26862 Aaron Lewis Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow KVD-26867 That Ain't Country KVD-51936 Old Lamplighter KVD-32784 Aaron Watson 1950's Standard Outta Style KVD-55022 An Affair To Remember KVD-34148 That Look KVD-50535 1950s Standards ABBA Crawdad Song KVD-25657 Gimme Gimme Gimme KVD-09159 It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas KVD-24881 My Love, My Life KVD-39233 1950s Standards (Male) One Man, One Woman KVD-39228 I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus KVD-29934 Under Attack KVD-20693 1960s Standard (Female) Way Old Friends Do KVD-32498 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31474 When All Is Said And Done KVD-30097 1960s Standard (Male) When I Kissed The Teacher KVD-17525 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31475 ABBA (Duet) 1970s Standards He Is Your Brother KVD-20508 After You've Gone KVD-27684 ABC 2Pac & Digital Underground When Smokey Sings KVD-27958 I Get Around KVD-29046 AC-DC 2Pac & Dr. -

Head to Hand Online Vol 1

2020 HEAD HAND HEADtoHAND MANAGING EDITOR/FACULTY SPONSOR: AZIZAT DANMOLE PRESIDENT/CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER/EDITOR: SARAH BURT ASSISTANT EDITOR: EMILY VINCENT ASSISTANT EDITOR: CHRISTOPHER J. WRIGHT COVER ART: “HUNTER” BY MAKYLA GREEN BACK COVER: SPECIAL THANKS *All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior written consent of the managing editor, excepting brief quotes used in critical articles and reviews. Table of Contents Letter from the Editor...1 PHOTO “Sunset” Makyla Green...2 FICTION “A Guide to Raising the Dead” by Emily Vincent …….3-6 PHOTO “Mosiac”....7 FICTION “Floaters” by Nicholas Wittenauer ...8-10 PHOTO “Pink” ...11 FICTION “Angie and Wallace” by Adam Harbison...12-13 PHOTO “Path”...14 POETRY “Chessboard” by Juliana Pettis ...15 PHOTO “Cuticle”...16 POETRY “Joan D’Arc “ by Adam Harbison ...17-18 PHOTO “Part”...19 POETRY “Made of New Orleans” by Adam Harbison...20 PHOTO “Seat” ...21 NONFICTION “I Like Pink and Blue” by Brooke Kalous...22-25 PHOTO “Trail”...26 NONFICTION “The Arrow” by Nicholas Wittenauer...27-28 PHOTO “Weights”...29 NONFICTION “Talk Me Down” by Mikalyn Hart...30 PHOTO ”Bright” Makyla Green...31 NONFICTION “A Two-Edged Sword” by Juliana Pettis...32-36 CONTRIBUTORS ...37-39 WARNING OF MATURE CONTENT IN SOME STORIES Letter from the Editor Dear Reader, You know what they say about hindsight, and this particular year is one in which we might think of reflecting a tiny bit. Of course, there are all sorts of new things being planned for the second decade of the millenium--new tech gadgets, phone apps, and cars that will actually be autonomous. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

LEADER COURAGE WHEN ADDRESSING PROBLEM BEHAVIORS IN AGRICULTURAL FRATERNITIES By JACK CAUSSEAUX A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2020 © 2020 Jack Causseaux To my friends, colleagues, family, and above all, to my future husband, Justin ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Conducting and completing this dissertation has been an exciting, educational, and challenging project. I must acknowledge and thank many people that supported me along the way. I had several mentors, teachers, and cheerleaders throughout my education and particularly throughout my pursuit of this PhD. First I would like to thank the University of Florida as my employer for affording me the opportunity to pursue this degree. Very special gratitude goes to my boss, my colleague, my mentor, and my friend, Dr. Nancy Chrystal-Green. She gave me unwavering grace and patience as I worked full-time while also working to achieve this goal. Her frank, yet astute guidance and perception of me has always been welcome and enlightening. I want to thank my parents, Kevin and Annette, for raising me in an environment in which education was valued. They supported me emotionally and financially through this process, and they kept me grounded in knowing that this, too, could be achieved. My brother Alec, my sisters Kelly and Katie, my sister-in-law Amanda, and my brothers- in-law Cody and Alex all deserve my thanks, as well. They have been a loving and supportive family, especially through the years it has taken me to finish this dissertation and degree. -

Las Hijas De Violencia: Performance, the Street, and Online Discourse

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2018 Las Hijas de Violencia: Performance, the Street, and Online Discourse Madison M. Snider University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, Social Media Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Snider, Madison M., "Las Hijas de Violencia: Performance, the Street, and Online Discourse" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1453. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1453 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. LAS HIJAS DE VIOLENCIA: PERFORMANCE, THE STREET, AND ONLINE DISCOURSE __________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts __________ by Madison M. Snider June 2018 Advisor: Erika Polson, Ph.D. ©Copyright by Madison M. Snider 2018 All Rights Reserved Author: Madison M. Snider Title: LAS HIJAS DE VIOLENCIA: PERFORMANCE, THE STREET, AND ONLINE DISCOURSE Advisor: Erika Polson, Ph.D. Degree Date: June 2018 ABSTRACT This paper explores street harassment as a contentious practice in the rhetorical spaces of the street and social media posting through a case study of the performance group Las Hijas de Violencia. Through anarchistic direct action resistance tactics, the group confronted harassers in the streets of Mexico City and their recordings launched global media interest which led to viral online sharing. -

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst THE COMPLETE POETRY OF JAMES HEARST Edited by Scott Cawelti Foreword by Nancy Price university of iowa press iowa city University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright ᭧ 2001 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Sara T. Sauers http://www.uiowa.edu/ϳuipress No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The publication of this book was generously supported by the University of Iowa Foundation, the College of Humanities and Fine Arts at the University of Northern Iowa, Dr. and Mrs. James McCutcheon, Norman Swanson, and the family of Dr. Robert J. Ward. Permission to print James Hearst’s poetry has been granted by the University of Northern Iowa Foundation, which owns the copyrights to Hearst’s work. Art on page iii by Gary Kelley Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hearst, James, 1900–1983. [Poems] The complete poetry of James Hearst / edited by Scott Cawelti; foreword by Nancy Price. p. cm. Includes index. isbn 0-87745-756-5 (cloth), isbn 0-87745-757-3 (pbk.) I. Cawelti, G. Scott. II. Title. ps3515.e146 a17 2001 811Ј.52—dc21 00-066997 01 02 03 04 05 c 54321 01 02 03 04 05 p 54321 CONTENTS An Introduction to James Hearst by Nancy Price xxix Editor’s Preface xxxiii A journeyman takes what the journey will bring. -

Madrigal Brass Quintet

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 4-16-2007 Madrigal Brass Quintet Tim Dillow Trumpet Illinois State University Becky Gawron Trumpet Kayla Jahnke Horn Nick Benson Trombone Dakota Pawlicki Tuba Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Dillow, Tim Trumpet; Gawron, Becky Trumpet; Jahnke, Kayla Horn; Benson, Nick Trombone; and Pawlicki, Dakota Tuba, "Madrigal Brass Quintet" (2007). School of Music Programs. 3161. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/3161 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Illinois State (jniversit_y College offine Arts I School of Music Madrigal l)rass Quintet I Tim Dillow & l)eck:i Gawron, Trumpd Ka:ila Jahnke, Horn Nick E,enson, Trombone! I Dakota F awlicki, Tuba I Flease tum oft cell phones and pagers for the duration of the concert. Thank You. Mini Overture Witold Lutoslawski I (1913-1994) Colchester Fantasy Eric Ewazen The Rose and Crown (born 1954) The Marquis of Granby I, The Dragoon The Red Lion - I ~Intermission~ I Three Dance Impressions Morley Calvert With dignity (1928-1991) With elegance I With humour 0 Magnum Mysterium Morten Lauridsen (born 1943) I Firedance Anthony DiLorenzo · (born 1967) I Kemp R.ecital Hall April I 6, 2007 I Monda_y E_vening 8:+5 p.m. -

00:00:00 Music Music “Crown Ones” Off the Album Stepfather by People Under the Stairs

00:00:00 Music Music “Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under The Stairs 00:00:05 Oliver Wang Host Hello, I’m Oliver Wang. 00:00:06 Morgan Host And I’m Morgan Rhodes. You’re listening to Heat Rocks. Rhodes Every episode we invite a guest to join us to talk about a heat rock. You know, fire, combustibles, an album that bumps eternally. And today we will be deep diving together into Nina Simone’s 1969 album, To Love Somebody. 00:00:22 Music Music “I Can’t See Nobody” off the album To Love Somebody by Nina Simone fades in. A jazz-pop song with steady drums and flourishing strings. I used to smile and say “hello” Guess I was just a happy girl Then you happened This feeling that possesses me [Music fades out as Morgan speaks] 00:00:42 Morgan Host Nina Simone’s To Love Somebody turned fifty this year. It was released on the first day of 1969, the same day the Ohio State beat the University of Southern California at the Rose Bowl for the National College Football Championship. It was her 21st studio album. There were dozens more still to come. You know them. Black Gold, Baltimore, Fodder on My Wings, stacks of albums. By the time we met up with Nina again for these nine songs, she had already talked about on “Mississippi Goddamn”, “Backlash Blues,” and “Strange Fruit,” and been about it with her activism, lived, spoken, suffered for. To Love Somebody is an oral representation of what breathing on a track means. -

Rose Culture for Georgia Gardeners Contents

Rose Culture for Georgia Gardeners Contents Picking the Planting Site ................................................. 3 Preparing the Soil ...................................................... 3 Buying Plants ......................................................... 4 Selecting Rose Cultivars ................................................. 4 Planting .............................................................. 5 Mulching ............................................................. 6 Watering ............................................................. 6 Fertilizing ........................................................... 1 0 Pruning and Grooming ................................................. 1 0 Cutting Roses ........................................................ 1 1 Controlling Pests ...................................................... 1 1 Diseases ......................................................... 1 2 Viral Diseases .................................................... 1 3 Insects and Mites .................................................. 1 3 Rose Societies in Georgia ............................................... 1 4 Rose Culture for Georgia Gardeners Gary L. Wade and James T. Midcap (Retired), Extension Horticulturists Jean Williams-Woodward, Extension Plant Pathologist Beverly Sparks, Associate Dean for Extension and Entomologist oses are a favorite of Georgia gardeners. Today, Next to sunlight, nothing is more important for suc- R thanks to selective breeding programs of cessful rose culture than the -

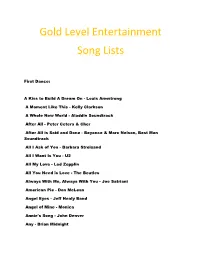

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists First Dance: A Kiss to Build A Dream On - Louis Armstrong A Moment Like This - Kelly Clarkson A Whole New World - Aladdin Soundtrack After All - Peter Cetera & Cher After All is Said and Done - Beyonce & Marc Nelson, Best Man Soundtrack All I Ask of You - Barbara Streisand All I Want Is You - U2 All My Love - Led Zepplin All You Need is Love - The Beatles Always With Me, Always With You - Joe Satriani American Pie - Don McLean Angel Eyes - Jeff Healy Band Angel of Mine - Monica Annie's Song - John Denver Any - Brian Midnight As Long as I'm Rocking With You - John Conlee At Last - Celine Dion At Last - Etta James At My Most Beautiful - R.E.M. At Your Best - Aaliyah Battle Hymn of Love - Kathy Mattea Beautiful - Gordon Lightfoot Beautiful As U - All 4 One Beautiful Day - U2 Because I Love You - Stevie B Because You Loved me - Celine Dion Believe - Lenny Kravitz Best Day - George Strait Best In Me - Blue Better Days Ahead - Norman Brown Bitter Sweet Symphony - Verve Blackbird - The Beatles Breathe - Faith Hill Brown Eyes - Destiny's Child But I Do Love You - Leann Rimes Butterfly Kisses - Bob Carlisle By My Side - Ben Harper By Your Side - Sade Can You Feel the Love - Elton John Can't Get Enough of Your Love, Babe - Barry White Can't Help Falling in Love - Elvis Presley Can't Stop Loving You - Phil Collins Can't Take My Eyes Off of You - Frankie Valli Chapel of Love - Dixie Cups China Roses - Enya Close Your Eyes Forever - Ozzy Osbourne & Lita Ford Closer - Better than Ezra Color My World - Chicago Colour