Anna B's Owner, a Short Story by Judith Mercado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Florida Keys Vessel Pumpout Facilities Marine Sanitation Device

Marine Sanitation Device Discharge Regulations Effective: December 27, 2010 Activities prohibited Sanctuary-Wide: q Discharge of sewage incidental to vessel use and generated by a marine sanitation device in accordance with the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (also called the Clean Water Act). q Having a marine sanitation device that is not secured in a manner that prevents discharges or deposits of treated and untreated sewage. Acceptable methods include, but are not limited to, all methods that have been approved by the U.S. Coast Guard. Pumpout facilities are located throughout the Keys to assist boat operators in complying with this rule. For a list of pumpout facilities, visit http://www.dep.state.fl.us/cleanmarina/about.htm. Florida Keys Vessel Pumpout Facilities * Designated Clean Marina Facility Key West Duck Key Mobile Pumpout Services • A & B Marina • Hawk’s Cay Resort Marina Free pumpout services for vessels • Conch Harbor Marina* anchored within unincorporated Long Key • City Marina at Garrison Bight* Monroe County (Key Largo, • Key West Bight Marina* • Fiesta Key KOA Tavernier, Cudjoe, Big Pine, Stock Stock Island Upper Matecumbe Key Island, etc.) and the Village of • Stock Island Marina Village • Bayside Marina- World Wide Sportsman* Islamorada. • Sunset Marina • Coral Bay Marina • Pumpout USA at 305-900-0263 or visit www.po-keys.com. Lower Keys Plantation Key • Plantation Yacht Harbor* • Bahia Honda State Park* • City of Key West 305-292-8167 • Sunshine Key RV Resort & Marina • Treasure Harbor Marine* • Stock Island, Mark LPS 305-587-2787 Marathon Tavernier • City of Marathon 305-289-8877 • Boot Key Harbor City Marina • Mangrove Marina • Key Colony Beach 305-289-1310 • Burdines Waterfront • Marathon Yacht Club Key Largo • Panchos Fuel Dock & Marina • All Keys Portalet Tips: • Sombrero Marina Dockside* • John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park* • Check with marina ahead of time on • Manatee Bay Marina status of pumpout equipment. -

Collier Miami-Dade Palm Beach Hendry Broward Glades St

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission F L O R ID A 'S T U R N P IK E er iv R ee m Lakewood Park m !( si is O K L D INDRIO ROAD INDRIO RD D H I N COUNTY BCHS Y X I L A I E O W L H H O W G Y R I D H UCIE BLVD ST L / S FT PRCE ILT SRA N [h G Fort Pierce Inlet E 4 F N [h I 8 F AVE "Q" [h [h A K A V R PELICAN YACHT CLUB D E . FORT PIERCE CITY MARINA [h NGE AVE . OKEECHOBEE RA D O KISSIMMEE RIVER PUA NE 224 ST / CR 68 D R !( A D Fort Pierce E RD. OS O H PIC R V R T I L A N N A M T E W S H N T A E 3 O 9 K C A R-6 A 8 O / 1 N K 0 N C 6 W C W R 6 - HICKORY HAMMOCK WMA - K O R S 1 R L S 6 R N A E 0 E Lake T B P U Y H D A K D R is R /NW 160TH E si 68 ST. O m R H C A me MIDWAY RD. e D Ri Jernigans Pond Palm Lake FMA ver HUTCHINSON ISL . O VE S A t C . T I IA EASY S N E N L I u D A N.E. 120 ST G c I N R i A I e D South N U R V R S R iv I 9 I V 8 FLOR e V ESTA DR r E ST. -

Florida Keys Destination Guide

s y e .k a l f . The Florida Keys & Key West: 0 80 . come as you are 1 m o .c s y ke - la f fla-keys.com 1.800.fla.keys THE FLORIDA KEYS Most people know the Florida Keys and Key West as a great getaway. One of the most unique places on earth. Calm. Serene. Laid back. Just the right setting to recharge your batteries and rejuvenate your spirits. But a getaway to the Florida Keys and Key West is much more than peace and quiet. And not just because of the legendary fishing and the world’s most spectacular dive sites. The Keys mean history. Art. Theater. Museums. Shopping. Fine dining. Entertainment. And much more. All told, 120 miles of perfect balance between natural beauty and extra-ordinary excitement. Between relaxation and activities. Between the quaint and the classic. And you’ll find our accommodations just as diverse as our pleasures. From some of the best camping spots in the country to luxurious hotels. From charming bed-and-breakfasts to rustic, family-owned lodgings. In other words, we’ve got something for everyone. In the next few pages you’ll get to know what your Florida Keys vacation can and will be like. What you’d expect. And what will surprise you. Our fame and our secrets. We figured we owed it to you. After all, we wouldn’t want you to get here and wish you had booked just a few more days. For the latest on health & safety protocols in The Florida Keys, please visit our website. -

Florida Keys Vessel Pump-Outs Boaters

Boaters: Vessel Sewage Restrictions Protect Our Environment Good water quality is essential to a healthy Florida Keys’ marine ecosystem. q Discharging treated or untreated sewage from your boat’s marine head (Marine Sanitation Device [MSD]) into the waters of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary is prohibited. q To help prevent unintentional discharges of treated or untreated sewage into the marine environment, MSDs must be secured and locked at all times. Acceptable methods for securing MSDs include, but are not limited, to those approved by the U.S. Coast Guard. (33 CFR 159.7) Pump-out facilities are located throughout the Keys to assist boat operators in adhering to these rules, which help protect people and marine life from potentially harmful vessel sewage discharges. Florida Keys Vessel Pump-Outs Key West Marathon Yacht Club* South Miami-Dade A & B Marina (for guests only) Sombrero Marina/Dockside Lounge * Blackpoint Marina Boca Chica Marina Naval Air Station* Key Colony Beach Homestead Bayfront Park Conch Harbor Marina* Key Colony Beach Marina City of Key West Marina Garrison Bight* Duck Key Mobile Pump-Out Services Key West Bight City Marina* Hawk’s Cay Resort & Marina From a vessel: Pumpout Key West Conch Harbor Marina* Upper Matecumbe Key USA 305-900-0263 or King’s Point Marina Bayside World Wide Sportsman* www.po-keys.com Galleon Marina (for guests only) Coral Bay Marina From land: All Keys Garrison Bight City Marina* Windley Key Portalet 305-664-2226 Margaritaville Key West Resort & Snake Creek Marina Marina (for guests only) Plantation Key Tips: Ocean Key Resort & SPA* Plantation Yacht Harbor* aCheck with marinas Stock Island Smuggler’s Cove Marina ahead of time on status Ocean Edge Key West Hotel & Marina Treasure Harbor Marine, Inc.* of pump-out equipment. -

Monroe County Stormwater Management Master Plan

Monroe County Monroe County Stormwater Management Master Plan Prepared for Monroe County by Camp Dresser & McKee, Inc. August 2001 file:///F|/GSG/PDF Files/Stormwater/SMMPCover.htm [12/31/2001 3:10:29 PM] Monroe County Stormwater Management Master Plan Acknowledgements Monroe County Commissioners Dixie Spehar (District 1) George Neugent, Mayor (District 2) Charles "Sonny" McCoy (District 3) Nora Williams, Mayor Pro Tem (District 4) Murray Nelson (District 5) Monroe County Staff Tim McGarry, Director, Growth Management Division George Garrett, Director, Marine Resources Department Dave Koppel, Director, Engineering Department Stormwater Technical Advisory Committee Richard Alleman, Planning Department, South Florida WMD Paul Linton, Planning Department, South Florida WMD Murray Miller, Planning Department, South Florida WMD Dave Fernandez, Director of Utilities, City of Key West Roland Flowers, City of Key West Richard Harvey, South Florida Office U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Ann Lazar, Department of Community Affairs Erik Orsak, Environmental Contaminants, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Gus Rios, Dept. of Environmental Protection Debbie Peterson, Planning Department, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Teresa Tinker, Office of Planning and Budgeting, Executive Office of the Governor Eric Livingston, Bureau Chief, Watershed Mgmt, Dept. of Environmental Protection AB i C:\Documents and Settings\mcclellandsi\My Documents\Projects\SIM Projects\Monroe County SMMP\Volume 1 Data & Objectives Report\Task I Report\Acknowledgements.doc Monroe County Stormwater Management Master Plan Stormwater Technical Advisory Committee (continued) Charles Baldwin, Islamorada, Village of Islands Greg Tindle, Islamorada, Village of Islands Zulie Williams, Islamorada, Village of Islands Ricardo Salazar, Department of Transportation Cathy Owen, Dept. of Transportation Bill Botten, Mayor, Key Colony Beach Carlos de Rojas, Regulation Department, South Florida WMD Tony Waterhouse, Regulation Department, South Florida WMD Robert Brock, Everglades National Park, S. -

Water Quality Concerns in the Florida Keys: Sources, Effects, and Solutions

WATER QUALITY CONCERNS IN THE FLORIDA KEYS: SOURCES, EFFECTS, AND SOLUTIONS PREPARED BY WILLIAM L. KRUCZYNSKI PROGRAM SCIENTIST FLORIDA KEYS NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY WATER QUALITY PROTECTION PROGRAM SEPTEMBER 1999 FLORIDA KEYS NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY WATER QUALITY PROTECTION PROGRAM STEERING COMMITTEE John H. Hankinson, Jr., Regional Administrator U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 4 Kirby B. Greene, III, Deputy Secretary Florida Department of Environmental Protection Jeff Benoit, Director Ocean and Coastal Resosurces Management National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Richard G. Ring, Superintendent Everglades National Park Colonel Joe R. Miller, District Engineer U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Jacksonville District David Ferrell U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service James Murley, Secretary Florida Department of Communities Affairs James Heber, Director Onsite Sewage Program Florida Department of Health Mitchell W. Berger Governing Board South Florida Water Management District James C. Reynolds, Deputy Executive Director Florida Keys Aqueduct Authority Commissioner Keith Douglass Board of County Commissioners Monroe County William H. Botten City of Key Colony Beach Commissioner Jimmy Weekly City of Key West i Charley Causey Florida Keys Environmental Fund Mike Collins Florida Keys Guide Association Karl Lessard Monroe County Commercial Fishermen TECHNICAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE Dr. John C. Ogden, Director Florida Institute of Oceanography Dr. Eugene A. Shinn U.S. Geological Survey Center for Coastal Geology Dr. Jay Zieman University of Virginia Department of Environmental Sciences Dr. Alina Szmant University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science George Garrett Director of Marine Resources Monroe County Dr. Erich Mueller Mote Marine Laboratory Pigeon Key Marine Research Center Dr. Ronald Jones, Director Southeast Environmental Research Program Florida International University Dr. -

Key West, Will Open the Way to the Much-Anticipated Porky’S Bayside BBQ and Everybody Seems to Be Here a Whole Has Been “Up Every Monday, Many Asking About Bar Today

WWW.KEYSINFONET.COM WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 25, 2013 VOLUME 60, NO. 103 G 25 CENTS TOURISM Keys packed for holidays By SEAN KINNEY ent, as hotels and other Lodgings up and down the island chain but from this Thursday asked questions, they posted [email protected] accommodations Keyswide through the new year, “We’re on the door outside a list of are reporting booming busi- reporting strong business for season sold out. In fact, most of us [in restaurants open on Christmas In the tourism-driven ness for the holidays. Marathon] should be sold out.” Eve and Christmas Day. Florida Keys, the week “In our little corner of par- Town. “We’ve got all [11] of cent to Florida Keys Marathon The Key Largo Chamber of Lou Gammell, a longtime between Christmas and New adise here, things are really our rooms rented, all [14] of Airport, general manager and Commerce had more than 380 bartender at the iconic Year’s Day is perhaps the hopping,” said Barbara our rental boats are rented. partner Steve DeRoche said people stop through its Sloppy Joe’s on Duval Street busiest of the year and gives Maddox, co-owner of Porky’s is busy. Definitely this week is busy and 2013 as Overseas Highway location on in Key West, will open the way to the much-anticipated Porky’s Bayside BBQ and everybody seems to be here a whole has been “up every Monday, many asking about bar today. January-through-April season. adjoining Captain Pip’s for the holidays.” single month.” lodging and dining options, “Christmas, typically And from the look of Marina and Hideaway on the At the 40-room Coconut He said that on Tuesday, his according to office staff. -

5–21–02 Vol. 67 No. 98 Tuesday May 21, 2002 Pages

5–21–02 Tuesday Vol. 67 No. 98 May 21, 2002 Pages 35705–35890 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 23:20 May 20, 2002 Jkt 197001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\21MYWS.LOC pfrm01 PsN: 21MYWS 1 II Federal Register / Vol. 67, No. 98 / Tuesday, May 21, 2002 The FEDERAL REGISTER is published daily, Monday through SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Friday, except official holidays, by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, PUBLIC Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Act (44 U.S.C. Subscriptions: Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Committee of Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Superintendent of Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official edition. General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 Single copies/back copies: The Federal Register provides a uniform system for making available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general (Toll-Free) applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published FEDERAL AGENCIES by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Subscriptions: Paper or fiche 202–523–5243 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 202–523–5243 issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

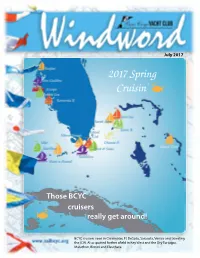

2017 Spring Cruisin'

July 2017 2017 Spring Cruisin' Those BCYC cruisers really get around! BCYC cruisers seen in Clearwater, Ft DeSoto, Sarasota, Venice and traveling the ICW. Also spotted farther afield in Key West and the Dry Tortugas, Marathon, Bimini and Eleuthera. Commodore’s Corner Submitted by Lee Nell, 2017 Commodore 2017 Flag Officers Calling all volunteers. I know you guys are probably tired of all my cries Commodore for more volunteers for this club. So if you want to stop me, just step Lee Nell forward and take over a task — I’ll stop. Seriously, though, this club is run by volunteers, many of whom handle multiple tasks throughout Vice Commodore the year. And many of those folks are weary and would appreciate help Bill Morse from other members. I know some of you members – some newer ones, Rear Commodore some longer-term – would like to help out but are not sure whether you would be welcome or how to sign up. Trust me, your assistance Rick Martin would be greatly welcomed. We will see that you have all the support Secretary you need, and we’d love for you to bring your own perspectives to the Linda Bagby project. Look in the Directory for contact information for your Board, and just let one of us know you might be interested. Treasurer Michael Oertle As I said last month, a good way to get started would be getting involved in planning for BCYC’s entry in the Gulfport July 4th parade. Assistant Treasurer Contact Barb Meyer or Lisa Glaser. Or me. The Fourth of July parade is Ray Weber always a great time, for us and for the City. -

View Our Current Map Listing

Country (full-text) State (full-text) State Abbreviation County Lake Name Depth (X if no Depth info) Argentina Argentina (INT) Rio de la Plata (INT) Rio de la Plata (From Buenos Aires to Montevideo) Aruba Aruba (INT) Aruba (INT) Aruba Australia Australia (INT) Australia (Entire Country) (INT) Australia (Entire Country) Australia Australia (INT) Queensland (INT) Fraser Island Australia Australia (INT) Cape York Peninsula (INT) Great Barrier Reef (Cape York Peninsula) Australia Australia (INT) New South Wales (INT) Kurnell Peninsula Australia Australia (INT) Queensland (INT) Moreton Island Australia Australia (INT) Sydney Harbor (INT) Sydney Harbor (Greenwich to Point Piper) Australia Australia (INT) Sydney Harbor (INT) Sydney Harbor (Olympic Park to Watsons Bay) Australia Australia (INT) Victoria (INT) Warrnambool Australia Australia (INT) Whitsunday Islands (INT) Whitsunday Islands Austria Austria (INT) Vorarlberg (INT) Lake Constance Bahamas Bahamas (INT) Bahamas (INT) Abaco Island Bahamas Bahamas (INT) Elbow Cay (INT) Elbow Cay Bahamas Bahamas (INT) Bahamas (INT) Eleuthera Island Bahamas Bahamas (INT) Bahamas (INT) Exuma Cays (Staniel Cay with Bitter Guana Cay and Guana Cay South) Bahamas Bahamas (INT) The Exumas (INT) Great Exuma and Little Exuma Islands Bahamas Bahamas (INT) Bahamas (INT) Long Island and Ruma Cay Bahamas Bahamas (INT) New Providence (INT) New Providence Bahamas Bahamas (INT) Bahamas (INT) San Salvador Island Bahamas Bahamas (INT) Waderick Wells Cay (INT) Waderick Wells Cay Barbados Barbados (INT) Barbados (Lesser Antilles) -

Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, Final Management Plan

Strategy for Stewardship Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary U.S. Department of Commerce Final Management National Oceanic and Plan/Environmental Atmospheric Administration National Ocean Service Impact Statement Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management Volume II of III Development of the Sanctuaries and Management Plan: Reserves Division Environmental Impact Statement This final management plan and environmental impact statement is dedicated to the memories of Secretary Ron Brown and George Barley. Their dedicated work furthered the goals of the National Marine Sanctuary Program and specifically the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. "We must continue to work together - inspired by the delight in a child's eye when a harbor seal or a gray whale is sighted, or the wrinkled grin of a fisherman when the catch is good. We must honor the tradition of this land's earliest caretakers who approached nature's gifts with appreciation and deep respect. And we must keep our promise to protect nature's legacy for future generations." - Secretary Ron Brown Olympic Coast dedication ceremony, July 16, 1994 "The Everglades and Florida Bay will be our legacy to our children and to our Nation." - George Barley Sanctuary Advisory Council Chairperson Cover Photos: Marine Educator--Heather Dine, Upper Keys Regional Office; Lobster Boats--Billy Causey, Sanctuary Superintendent; Divers--Harold Hudson, Upper Keys Regional Office; Dive Charter--Paige Gill, Upper Keys Regional Office; Coral Restoration--Mike White, NOAA Corps. Florida Keys Final -

Atlantic Coast: Cape Henry to Key West 2011 (43Rd) Edition

Atlantic Coast: Cape Henry to Key West 2011 (43rd) Edition This edition cancels the 42nd Edition, 2010, and has been corrected through 5th Coast Guard District Local Notice to Mariners No. 31/11 and the 7th Coast Guard District Local Notice to Mariners No. 31/11, and includes all previously published corrections. Changes to this edition will be published in the Fifth Coast Guard District Local Notice to Mariners, the Seventh Coast Guard District Local Notice to Mariners and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) Notice to Mariners. The changes also are available at http://nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/nsd/cpdownload.htm. U.S. Department of Commerce Dr. Rebecca M. Blank, Acting Secretary National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Jane Lubchenco, Ph.D., Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere, and Administrator, NOAA National Ocean Service David M. Kennedy, Assistant Administrator, National Ocean Service Washington, DC For sale by the National Ocean Service and its sales agents 344Miami to Key WestVolume 4 WK40/2011 Charts 11462, 11465, 11463, 11464, 11451 (50) A privately dredged channel, about 0.4 mile north- ward of the entrance to Ocean Reef Harbor, leads to a (40) Bowles Bank Anchorage, 6.5 miles south- residential area. The channel, marked by private day- southwestward of Fowey Rocks Light (25°35'26"N., beacons, had a centerline controlling depth of 7 feet in 80°05'48"W.), is fair in all but southerly winds. It has 1979. depths of 14 to 16 feet and soft bottom in places, and (51) Key Largo Anchorage, 20 miles southwestward of lies about 0.5 mile north of the light of Bache Shoal and Fowey Rocks Light, is fair in all but southerly winds.