Chatsea-WP-13-Katigbak.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Public Works and Highways Region Iv-A Quezon 2Nd District Engineering Office Lucena City

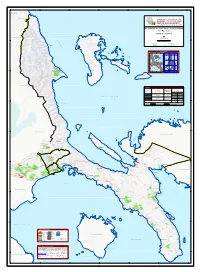

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS REGION IV-A QUEZON 2ND DISTRICT ENGINEERING OFFICE LUCENA CITY C.Y. 2021 PROJECT DETAILED ENGINEERING DESIGN PLAN FOR OO2: Protect Lives and Properties Against Major Floods, Flood Management Program, Construction/Maintenance of Flood Mitigation Structures and Drainage Systems, Construction of Seawall, Barangay Barra, Lucena City, Quezon ORIGINAL STATION LIMIT STA. 000+000.00 - STA. 000+205.00 L = 205.00 l.m. SUBMITTED: RECOMMENDED: APPROVED: FAUSTINO MARK ANTHONY WILFREDO L. RACELIS MA. CHYMBELIN D. IBAL S. DE LA CRUZ ENGINEER III ASSISTANT DISTRICT ENGINEER CHIEF, PLANNING AND DESIGN SECTION OIC - OFFICE OF THE ASSISTANT OIC - OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT DATE: DISTRICT ENGINEER ENGINEER DATE: DATE: PANUKULAN BURDEOS GENERAL NAKAR Palasan Island Burdeos Bay Patnanungan Island PULONG POLILLO Polillo Strait POLILLO RODRIGUEZ INFANTA A. GENERAL RIZAL TANAY G - 1 01/11 COVER SHEET BARAS REAL BINANGONAN FAMY PILILLA SINILOAN PANGIL G - 2 02/11 KEY MAP AND INDEX OF DRAWINGS PAETE TANZA Talim Island JALA-JALA Laguna de Bay NAIC DASMARIÑAS LUMBAN SANTA ROSA Cabalete Island Lamon Bay TERNATE PAGSANJAN CAVINTI G - 3 03/11 CABUYAO CAVITE SILANG LAGUNA CALAMBA MAUBAN AMADEO LOS BAÑOS PEREZ CALAUAN BAY LUCBAN PULONG ALABAT ALFONSO TAGAYTAY G - 4 04/11 NASUGBU GENERAL CONSTRUCTION NOTES Mount SAN PABLO Banahao Calauag Bay TALISAY QUEZON CALAUAG TAYABAS Lopez Bay QUEZON LUY TAGKAWAYAN ATIMONAN LIAN PAGBILAO CALACA LEMERY TIAONG B. ROADS BALAYAN LIPA LUCENA Pagbilao Grande Island CANDELARIA TAAL SARIAYA GUMACA SAN JOSE AGDANGAN PADRE GARCIA CALATAGAN Balayan Bay UNISAN GUINAYANGAN IBAAN ROSARIO BAUAN PITOGO LOPEZ 05/11 SUMMARY OF QUANTITIES BATANGAS MACALELON BATANGAS SAN JUAN MABINI BUENAVISTA GENERAL LUNA LOBO LAIYA 06/11 SEAWALL TYPICAL 1.0 TINGLOY PROJECT SITE CATANAUAN SAN NARCISO MULANAY 07/11 SEAWALL TYPICAL 2.0 SAN FRANCISCO 08/11 DPWH FIELD OFFICE SAN ANDRES 09/11 DPWH BILLBOARD B.2 PLAN AND PROFILE 10/11 PLAN AND PROFILE (STA. -

UM 121, S. 2020-Dqh50ufl103kx80

DepEd - DIVISION OF QUEZON Sitio Foti Btgy- Tdlipan, Pegh ao, Quezon TrunHine * (u2) 78143fi. (042) 78/4161, (012) 7844391, (042) 744321 w,,v,,v - de p &vezo n - com. pt1 "Creadng Potaibilili es, tnsfi ing trt or,,alions" Batch I School Head School Municipality Santiso, Vivian L. CABONG NHS Buenavista Nazareth, Joselito D. MALIGAYA NHS Buenavista Orlanda, Denisto S. APAD NHS Calauag Tan, Emily Paz Noves BANTULINAO IS Calauag DR. ARSENIO C. NICOLAS Gercfia, Jocl Lirn Ca{eueg NHS Moreno, Rafael Eleazar STO. ANGEL NHS Calauag Bonillo, Jessie Almazan MATANDANG SABANG NHS Calanauan SAN VICENTE KANLUMN Bandol, Silver Abelinde Catanauan NHS Rogel, lsabel Perjes TAGABAS IBABA NHS Calanauan Manalo, Florida Bartolome TAGBACAN NHS Catanauan Marjes,Carolina Alcolea STA. CRUZ NHS Guinayangan Vitar, Melquiades Luteri*a DAONHS Lopez Ronquillo, Bemadette Bemardo GUITES NHS Lopez Panotes, Adelia Ardiente PAMAMPANGIN NHS Lopez Itable, Nierito Petalcorin VERONICA NHS Lopez [4qntada, Miiricsa M. PISIPIS NHS Lopez Mllanueva, Edson A. STO. NINO ILAYA NHS Lopez Zulueta, Haniette B. ILAYANG ILOG-A NHS Lopez Callejo, Juanita MGSINAMO NHS Mauban Oseiia, Aurea Muhi MAGSAYSAY NHS Mulanay Coronacion, Mila Coralde BONBON NHS Panukulan Nazareno, Jiezle Kate Magno BUSDAK NHS Patnanungan Topacio, Sherre Ann, Constantino CABULIHAN NHS Pitogo Delos Santo's, Veneranda Almirez BALESIN IS Polillo Odiame, Francis B. HUYON-UYON NHS San Francisco Conea, Rafael Marumoto LUALHATI D. EDANO NHS San Francisco Castillo, Miguelito A PUGON NHS San Francisco RENATO EDANO VICENCIO Majadillas, Jomar Pensader San Francisco NHS Ranido, Miguel Onsay Jr. TUMBAGA NHS San Francisco DR. VIVENCIO V. MARQUEZ Magas, Danrin F. San Francisco NHS DEPEDOUEZON-Tli/LSDS-0,+{1 0-002 Email dddress: [email protected] Comnents: Trt HELEN - N17891t2327 (s.m8,slJ,fia otTxt) 2327 (c,oba an I ) @ Ihi. -

Republic of the Philippines Department of Agriculture Office of the Secretary Elliptical Road, Diliman, Quezon City

Republic of the Philippines Department of Agriculture Office of the Secretary Elliptical Road, Diliman, Quezon City FISHERIES ADMINISTRATIVE ) ORDER NO. 172 : Series of 2003…………………..) SUBJECT: Establishing a five-year closed season on the operation of commercial fishing boats and the employment of hulbot- hulbot by both commercial and municipal fishing boats in Polillo Strait and a portion of Lamon Bay, Quezon province. The following regulation for the protection and conservation of the fisheries and aquatic resources in Polillo Strait and a portion of Lamon Bay in Quezon province is hereby promulgated pursuant to Sections 3 (b), 4 and 7 of Presidential Decree No. 704, as amended, and Section 1, Presidential Decree No. 1015 for the information and guidance of all concerned: SECTION 1. Definition of terms. - The following terms as used in this Order shall be construed as follows: a) Polillo Strait and a portion of Lamon Bay, Quezon province - refers to that body of marine waters, beginning at a point marked "1" on the map being Deseada Point part of General Nakar, Quezon province which is 15° 15' 55" N. Latitude, 121° 28' 52" E. Longitude; thence to Point 2, Bulubalic Point of Polillo Island at 15° 02' 52" N. Latitude, 121° 59' 35" E. Longitude; thence to Point 3, Kalongkooan Island 14° 57' 18" N. Latitude, 122° 09' 35" E. Longitude; thence to Point 4 eastside tip of Jomalig Island 14° 42' 28" N. Latitude, 122° 26' 15" E. Longitude; thence to Point 5, Agta Point southern part of Polillo Island with 14° 37’ 45" N. Latitude, 121° 56' 18" E. -

Economic Evaluation of Fishery Policies in Lamon Bay, Quezon, Philippines

Economy and Environment Program for Southeast Asia Tanglin PO Box 101 Singapore 912404 Phone: (65) 6831-6854 Fax: (65) 6235-1849 E-mail: [email protected] R E S E A R C H R E P O R T Web site: www.eepsea.org NO. 2003-RR9 Economic Evaluation of Fishery Policies in Lamon Bay, Quezon, Philippines Maribec A. Campos, Blanquita R. Pantoja, Nerlita M. Manalili and Marideth R. Bravo. SEAMEO-SEARCA, Los Banos, Laguna, Philippines. ([email protected]) This report assesses the sustainability of fisheries of Lamon Bay in the Philippines and investigates the effectiveness of fishery conservation policies. It finds that current policies are failing and that a substantial investment would be required to ensure full compliance with current regulations. It also finds that the benefits of achieving high levels of compliance would exceed costs by only a tiny margin. It concludes that current regulations to deal with overfishing are neither cost-effective nor address the underlying problems of overexploitation of fish stocks and open access to fishing areas. The report suggests that a tradable quota system may provide one answer to the problem and outlines government policies that would back up such an approach. i Published by the Economy and Environment Program for Southeast Asia (EEPSEA) Tanglin PO Box 101, Singapore 912404 (www.eepsea.org) tel: +65-6235-1344, fax: +65-6235-1849, email: [email protected] EEPSEA Research Reports are the outputs of research projects supported by the Economy and Environment Program for Southeast Asia. All have been peer reviewed and edited. -

Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997

The IUCN Species Survival Commission Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997 Edited by Sarah L. Fowler, Tim M. Reed and Frances A. Dipper Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 25 IUCN The World Conservation Union Donors to the SSC Conservation Communications Programme and Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management: Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997 The IUCN/Species Survival Commission is committed to communicate important species conservation information to natural resource managers, decision-makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC's Action Plans, Occasional Papers, newsletter Species and other publications are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation. To date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to SSC Specialist Groups. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and support for species conservation worldwide. The Council of Agriculture (COA), Taiwan has awarded major grants to the SSC's Wildlife Trade Programme and Conservation Communications Programme. This support has enabled SSC to continue its valuable technical advisory service to the Parties to CITES as well as to the larger global conservation community. Among other responsibilities, the COA is in charge of matters concerning the designation and management of nature reserves, conservation of wildlife and their habitats, conservation of natural landscapes, coordination of law enforcement efforts as well as promotion of conservation education, research and international cooperation. -

Manual of Seaweed Production and Filed Guide of Discovery-Based

SAN AMM MAY Published jointly by Peace and Equity Foundation (PEF); and Social Action Center-Northern Quezon (SAC-NQ) Prelature of Infanta In collaboration with Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) Region IV-A; and Samahan ng Nagkakaisang Mangingisda at Magsasaka ng Mabobon (SANAMMMAY) MANUAL OF SEAWEED PRODUCTION AND FIELD GUIDE OF DISCOVERY-BASED EXERCISES FOR FARMER FIELD SCHOOLS Compiled and edited by DAMASO P. CALLO, JR. AND ALFREDO N. DARAG, JR. Final Draft, September 2015 Manual of Seaweed Production and Field Guide of Discovery-based Exercises for Farmer Field Schools. This manual-field guide is based from best practices and learning experiences shared by participants during a Workshop on Participatory Research and Learning of Seaweed Farmers Through the Farmer Field School Approach held in Maydalaga, Calutcot, Burdeos, Quezon, Philippines on 15-16 August 2013; by participants in Farmer Field School and Participatory Research and Learning on Seaweed Production undertaken in Calutcot- Kalongkoan Islands, Burdeos, Quezon, Philippines on August 2013 to May 2014; and by various stakeholders in their Research, Development and Extension (RD&E) activities from 2000-2013 in Quezon, Philippines, and elsewhere. Published jointly by Peace and Equity Foundation (PEF) Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines; Social Action Center-Northern Quezon (SAC-NQ) Prelature of Infanta, Infanta, Quezon, Philippines In collaboration with Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) SAN Region IV-A, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines; and AMM Samaahan ng Nagkakaisang Mangingisda at Magsasaka MAY ng Maybobon (SANAMMMAY) Calutcot, Burdeos, Quezon, Philippines Printed in the Republic of the Philippines First Printing, September 2015 Compiled and edited by Damaso P. -

1 7 JUN 30 P3 :?SI First Regular Session 1 SENATE S

FOURTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE 1 REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES 1 7 JUN 30 P3 :?SI First Regular Session 1 SENATE S. B. No. 21 Introduced bv SENATOR EDGARDO J. ANGARA EXPLANATORY NOTE This Act provides for the creation of an Authority that will negotiate with interested private investors and be responsible for the construction, operation, management and administration of the Quezon Canal and the Canal Zone from the Municipality of Atimonan to the Municipality of Unisan, both in the Province of Quezon. The Quezon Canal will provide a by-pass or short cut for ocean vessels coming from the eastern side of Luzon to Manila and the China Sea. It will also provide cheaper and faster transport of products from Luzon's eastern coastal towns to the metropolitan markets. The Canal will increase the volume of inter-island shipping and trade between, the coastal towns of Quezon, Marinduque, Mindoro, Batangas and Bicol Region. The untapped regions north of the Province of Quezon and the marine resources of Lamon Bay, Polillo Strait and Tayabas Bay will be open to development. The Canal Zone is envisioned as a major transhipment center to and from the United States, Japan and the ASEAN countries. Export processing facilities and light industries in the Canal Zone will boost our export potential and increase our industrial productivity. It will contribute immensely to the growth of our country's international trade and commerce. Furthermore, the Canal will stimulate the growth of tourist centers in the region. The Canal will increase the capability of the Philippine coast Guard to patrol and safeguard our eastern coastline. -

Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Ri

ABSTRACT This paper tells of the story of the struggles of artisanal fisherfolks in the CALABARZON (Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal and Quezon) Region in Luzon in the Philippines in terms of how they try to reclaim the foreshore lands, fishery and inland resources that are traditionally utilized by them. It is an attempt to document the different forms of commercialization in the foreshore areas, which often come in the forms of private beach resorts, reclamation projects and fishponds. These development aggressions have entirely altered the coastal and land uses in these areas as more and more traditional fishing grounds and foreshore lands are turned into eco-tourism and agri- business sites. This paper is a consolidation of three case studies made in Laguna Lake, the Municipality of Real in Quezon and the Municipality of Calatagan in Batangas. It is interesting to note how perceived development have led the way to foreshore land grabbing and displacement of fisherfolks from their traditional fishing grounds. It is also important to note how foreshore lands have taken its toll from the demands for fisherfolk settlement, reclamation for tourism purposes and conversion of mangroves into fishponds in the past. This paper suggests for the national government to address the seeming virtual privatization and commercialization of foreshore areas in the country. The increase in the number of private beach resorts and recreational areas are putting too much pressure to the productivity and social cohesion of coastal communities. Many fishing communities are being dislocated due to these trends. Key Words: commercialization, privatization, foreshore lands 1 COMMERCIALIZATION OF FORESHORE LANDS IN SELECTED MUNICIPALITIES IN THE CALABARZON REGION IN THE PHILIPPINES By: Mr. -

1 Economic Evaluation of Fisheries Policies in The

ECONOMIC EVALUATION OF FISHERIES POLICIES IN THE PHILIPPINES Maria Rebecca A. Campos, Ph.D. Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture (SEARCA) Los Banos, Laguna, Philippines [email protected] Abstract The Philippines is surrounded with many fishing grounds. In spite of this, most fishermen in the area live in poverty, and their plight is getting worse, not better. Current fisheries policies for the area have failed to improve the situation but no research has been done to find out why. This report attempts to fill this information gap about the reasons for policy failure. Drawing on data from secondary sources and an original survey, it uses a bioeconomic model to simulate the effects of changes in the enforcement levels of three current policies: ban on electric shiners, fish cage regulation, and regulation of both electric shiners and fish cages. Investments of the government on different levels of enforcement were assessed using benefit cost analysis. The report assesses the effects of enforcing current fisheries policies more stringently. It finds that a substantial investment (PHP 614,000 per year) would be required to ensure compliance with regulations and that the benefits of achieving high levels of compliance would exceed costs by only a tiny margin. The situation would be transformed into one in which large and perhaps increasing numbers of people would continue to fish, expending larger amounts of effort to comply with various gear restrictions but, in all likelihood, harvesting no fewer fish. Because the bay is already overfished, catch per unit effort and marginal productivity would decrease. -

Attractiveness of Tourism Industry in Calabarzon: Inputs to Business Operations Initiatives

[Valdez et. al., Vol.7 (Iss.4): April 2019] ISSN- 2350-0530(O), ISSN- 2394-3629(P) DOI: https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v7.i4.2019.894 Management ATTRACTIVENESS OF TOURISM INDUSTRY IN CALABARZON: INPUTS TO BUSINESS OPERATIONS INITIATIVES Elroy Joseph C. Valdez *1, 2 *1 College of Accountancy, Business, Economics and International Hospitality Management, Batangas State University, Philippines 2 College of International Tourism and Hospitality Management, Lyceum of the Philippines University - Batangas, Philippines Abstract This study will identify the attractiveness of tourism in CALABARZON. More specifically: it will to evaluate the level of attractiveness of tourism industry in CALABARZON in terms of cultural proximity, destination environment, price, destination image, risk and reward, and geographical proximity; to test if investment climate significantly affects attractiveness of tourism industry in CALABARZON; to propose a tourism development plan based on the results. The researcher used descriptive method to determine the investment climate and attractiveness of tourism industry in CALABARZON. The questionnaire is one of the major instruments used by the researcher to gather and collect the needed data. Results showed that majority of the respondents belonged to the young age group, female, single, college graduate and has an average income. The tourists, local residents and local government unit all agreed that CALABARZON region is moderately attractive to tourists due to competitors of tourist destination on the good services provided among them. Investment climate has an effect on the attractiveness of the tourism industry in CALABARZON region. The researcher proposed business operations initiative win order for the tourism industry in CALABARZON region more competitive. -

Darwin Initiative for the Survival of Species Annual Report 01 February 2005 to 31 March 2006

Darwin Initiative for the Survival of Species Annual Report 01 February 2005 to 31 March 2006 1. Darwin Project Information Project Reference Number 162 / 13 / 025 Project Title Pioneering Community-Based Conservation Sites in the Polillo Islands (PCBCSPI) Country Philippines UK Contractor Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Partner Organisation Polillo Islands Biodiversity Conservation Foundation, Inc. (PIBCFI) Darwin Grant Value £169,050.00 Start/End Dates February 2005 – January 2008 Reporting Period and Report Number 01 February 2005 to 31 March 2006 (Report #1) Project Website Not yet available Authors William Oliver, Neil Aldrin Mallari, Errol Gatumbato and Arturo Manamtan 2. Project Area and Background The Polillo Archipelago in the Philippines is composed of 27 small islands and islets situated in Lamon Bay, 29 kilometers off the east coast of Luzon facing the Pacific Ocean. It forms part of Quezon Province in Region IVa or CALABARZON (Provinces of Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal and Quezon) and comprises a total of five municipalities, namely: Polillo, Burdeos, Panukulan, Patnanungan and Jomalig. This group of islands forms one of the most distinct sub-centres of endemicity within the ‘Greater Luzon Faunal Region’ or ‘Luzon Endemic Bird Area (EBA)’; one of the world’s highest conservation priority areas in terms of both numbers of threatened species represented and degrees of threat. The Polillos support several endemic species and subspecies of birds, reptiles and invertebrates, as well important populations of various globally threatened species, including the Philippine cockatoo (Cacatua haematuropygia), Gray’s monitor lizard (Varanus olivaceus) and Philippine jade vine (Strongylodon macrobothrys). This Polillo Islands have accordingly been recognised as a high conservation priority area all recent independent reviews on conservation priority areas of the Philippines. -

NUTRIENT STATUS MAP : MAGNESIUM ( Key Rice Areas )

121°15' 121°30' 121°45' 122° 122°15' 122°30' 122°45' 15°15' Province of D i n g a l a n B a y Nueva Ecija Province of Aurora R E P U B L I C O F T H E P H I L I P P I N E S D E PA R T M E N T O F A G R IIC U LT U R E BUREAU OF SOILS AND WATER MANAGEMENT Elliptical Road Cor. Visayas Ave., Diliman, Quezon City NUTRIENT STATUS MAP : MAGNESIUM ( Key Rice Areas ) PROVINCE OF QUEZON Province of Bulacan ° SCALE 1:200,000 P 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 15° 15° O L Kilometers L I L O Projection : Transverse Mercator S Datum : PRS 1992 T R DISCLAIMER : All political boundaries are not authoritative A I Panukulan T ! A n i b a w a n B a y !Burdeos LOCATION MAP 20° 15° Rizal 14°30' LUZON 15° Patnanungan B u r d e o s B a y ! Laguna Camarines Norte 14° VISAYAS QUEZON 10° Batangas 13°30' !General Nakar Marinduque MINDANAO Polillo 14°45' 14°45' Infanta ! Oriental 5° ! Mindoro 121°30' 122° 122°30' 120° 125° !Jomalig !Real Province of Rizal LEGEND Exchangeable Mg, AREA MAPPING UNIT DESCRIPTION cmol/kg ha % 5 ,288 15.17 Sufficient >1.0 P H I L I P P I N E S E A 2 8,079 80.54 - - Deficient 1.0 and below 1 ,496 4.29 14°30' 14°30' TOTAL 34,863 100.00 L a m o n B a y Paddy Irrigated Paddy Non - irrigated Area estimated based on actual field survey, other information from DA-RFO's, MA's NIA Service Area, NAMRIA Land Cover (2010) and BSWM Land Use System Map.