Miriam Makeba: "Mama Africa"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review: International Jazz Day, Istanbul

jazzjo urnal.co .uk http://www.jazzjournal.co.uk/magazine/583/review-international-jazz-day-istanbul Review: International Jazz Day, Istanbul N. Buket Cengiz reports on an event marked by star-studded concerts and discussions that revealed the ’heretofore unknown’ rhetorical powers of bassist Marcus Miller On 30 April, the sun shone with the hum of jazz tunes in Istanbul, inviting Istanbulites to wake up f or a day of a sweet rush in the host city f or International Jazz Day 2013. The 32nd International Istanbul Film Festival, a major cinema f estival in Europe, had been wrapped up just a couple of weeks prior with yet another collection of unf orgettable memories, and the city was ready f or the International Jazz Day event to be celebrated in collaboration with the Republic of Turkey and Istanbul Jazz Festival as the host city partner, with preparations underway since winter. In Istanbul, culture and arts as well as night lif e are remarkable, particularly f or music enthusiasts. Throughout the year, there is an abundance of clubs to choose f rom, and thanks to its temperate climate, there are open air concerts and f estivals as well. All year round, rock and indie, classical, ethnic and f olk, and of course jazz tunes f lit about the city, particularly during the never-ending summer nights. Istanbul is proud of its two international jazz f estivals: The Istanbul Jazz Festival organized by Istanbul Foundation f or Culture and Arts (IKSV), which will celebrate its 20th anniversary this July, and the Akbank Jazz Festival, which will be held f or the 23rd time this September. -

Fantasticks 2 Playbill

JUNE 7 - JULY 1 Sales Exchange Co., Inc. Jewelers and Collateral Loanbrokers Classic and Contemporary Platinum and Gold Jewelry designs that will excite your senses. One East Main St., Patchogue 631.289.9899 www.wmjoneills.com Mention this ad for 10% discount on purchase 2 The Pine Grove Inn has served generations of guests since its establishment in 1910. Our seasonal menus emphasize prime beef, fresh local seafood and the traditional German fare which made us famous. The Palm Bar & outdoor patio overlooks the Swan River. $6 Martinis Enjoy Live Music Thursday through Saturday Tuesday through Friday Open for Lunch and Dinner Wednesday through Sunday from 4-7 at the bar Available for Parties Monday & Tuesday Choose us for your next special event – our catering department will be pleased to work with you to design your affair Wednesday Lobsterfest Thursday Prime Rib Night Chapel Avenue & First St., Patchogue, NY 11772 • 631.475.9843 www.pinegroveinn.com PRESENT THIS VOUCHER FOR PRESENT THIS VOUCHER FOR $5 OFF LUNCH $10 OFF DINNER on checks of $30 or more on checks of $60 or more Expires July 7, 2006. Reservations suggested. Expires July 7, 2006. Reservations suggested. May not be combined with any other promotional offer. May not be combined with any other promotional offer. Specialists in Family Owned & Quality & Service Operated Since 1976 1135 Montauk Hwy., Mastic • 399-1890/653-RUGS 721 Rte. 25A (next to Personal Fitness), Rocky Point • 631-744-1810 Open 7 Days We love it when you love what you’re walking on. 4 European-style Desserts and Espresso Drinks Open Late 6 Nights per Week Signature Martini Bar Outdoor Café Seating Live Jazz Every Thursday & Restaurant Late Night Friday Zagat Rated Excellent 2001-2006 14 Station Road, Bellport Village 286-3300 GATEWAY PLAYHOUSE 2006 5 E HARBOR SID TH “Incomparable Seafood Restaurant” E Highly Recommended: Open 7 Days a Week * * * at 11:30 a.m. -

Central Reference CD List

Central Reference CD List January 2017 AUTHOR TITLE McDermott, Lydia Afrikaans Mandela, Nelson, 1918-2013 Nelson Mandela’s favorite African folktales Warnasch, Christopher Easy English [basic English for speakers of all languages] Easy English vocabulary Raifsnider, Barbara Fluent English Williams, Steve Basic German Goulding, Sylvia 15-minute German learn German in just 15 minutes a day Martin, Sigrid-B German [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Dutch in 60 minutes Dutch [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Swedish in 60 minutes Berlitz Danish in 60 minutes Berlitz Norwegian in 60 minutes Berlitz Norwegian phrase book & CD McNab, Rosi Basic French Lemoine, Caroline 15-minute French learn French in just 15 minutes a day Campbell, Harry Speak French Di Stefano, Anna Basic Italian Logi, Francesca 15-minute Italian learn Italian in just 15 minutes a day Cisneros, Isabel Latin-American Spanish [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Latin American Spanish in 60 minutes Martin, Rosa Maria Basic Spanish Cisneros, Isabel Spanish [beginner’s CD language course] Spanish for travelers Spanish for travelers Campbell, Harry Speak Spanish Allen, Maria Fernanda S. Portuguese [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Portuguese in 60 minutes Sharpley, G.D.A. Beginner’s Latin Economides, Athena Collins easy learning Greek Garoufalia, Hara Greek conversation Berlitz Greek in 60 minutes Berlitz Hindi in 60 minutes Berlitz Hindi travel pack Bhatt, Sunil Kumar Hindi : a complete course for beginners Pendar, Nick Farsi : a complete course for beginners -

For Immediate Release

‘ICE DREAMS’ CAST BIOS SHELLEY LONG (Harriet Clayton) – Shelley Long is an Emmy® and Golden Globe-winning actress. She began her career after attending Northwestern University by performing in small films and local theater, eventually becoming co-host and associate producer of a critically acclaimed Chicago magazine show “Sorting it Out,” for which she won three local Emmys. She eventually returned to her first passion, acting, and joined Chicago’s famed Second City improvisational comedy troupe. Shortly after, Long landed a role as barmaid Diane Chambers in the long-running NBC comedy “Cheers.” Long entertained audiences for five seasons, garnering an Emmy and two Golden Globes. She returned for the series’ top-rated finale and has reprised her “Cheers” role in guest appearances on NBC’s “Frasier,” one episode garnering an Emmy nomination. Long recently starred in a film short titled “A Couple of White Chicks at the Hairdresser,” and starred in a children’s DVD, “Mr. Vinegar and the Curse.” In 2006, Long starred in “Honeymoon With Mom” on Lifetime, and co-starred in the Hallmark Channel Valentine’s Day movie, “Falling In Love with the Girl Next Door.” She has made a number of guest TV appearances including “Boston Legal,” “Yes, Dear, “Joan of Arcadia,” “Complete Savages” and, most recently, ABC’s hit comedy “Modern Family.” Long was seen in the Robert Altman film “Dr. T and the Women” for Artisan Entertainment. Written by Anne Rapp and executive produced by Cindy Cowan and James McLindon, the film tells the story of a gynecologist, played by Richard Gere, who is battling a mid-life crisis. -

Makers: Women in Hollywood

WOMEN IN HOLLYWOOD OVERVIEW: MAKERS: Women In Hollywood showcases the women of showbiz, from the earliest pioneers to present-day power players, as they influence the creation of one of the country’s biggest commodities: entertainment. In the silent movie era of Hollywood, women wrote, directed and produced, plus there were over twenty independent film companies run by women. That changed when Hollywood became a profitable industry. The absence of women behind the camera affected the women who appeared in front of the lens. Because men controlled the content, they created female characters based on classic archetypes: the good girl and the fallen woman, the virgin and the whore. The women’s movement helped loosen some barriers in Hollywood. A few women, like 20th century Fox President Sherry Lansing, were able to rise to the top. Especially in television, where the financial stakes were lower and advertisers eager to court female viewers, strong female characters began to emerge. Premium cable channels like HBO and Showtime allowed edgy shows like Sex in the City and Girls , which dealt frankly with sex from a woman’s perspective, to thrive. One way women were able to gain clout was to use their stardom to become producers, like Jane Fonda, who had a breakout hit when she produced 9 to 5 . But despite the fact that 9 to 5 was a smash hit that appealed to broad audiences, it was still viewed as a “chick flick”. In Hollywood, movies like Bridesmaids and The Hunger Games , with strong female characters at their center and strong women behind the scenes, have indisputably proven that women centered content can be big at the box office. -

2018 Discussion Guide

2018 Discussion Guide American Library Association Ethnic and Multicultural Information Exchange Round Table CORETTA SCOTT KING BOOK AWARDS COMMITTEE American Library Association Ethnic and Multicultural Information Exchange Round Table Coretta Scott King Book Awards Committee • www.ala.org/csk The Coretta Scott King Book Awards Discussion Guide was prepared by the 2018 Coretta Scott King Book Award Jury Chair Sam Bloom and members Kacie Armstrong, Jessica Anne Bratt, Lakeshia Darden, Sujin Huggins, Erica Marks, and Martha Parravano. The activities and discussion topics are developed to encompass state and school standards. These standards apply equally to students from all linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Students will demonstrate their proficiency, skills, and knowledge of subject matter in accordance with national and state stan- dards. Please refer to the US Department of Education website, www.ed.gov, for detailed information. The Coretta Scott King Book Awards seal was designed by artist Lev Mills in 1974. The symbolism of the seal reflects both Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s philosophy and the award’s ideals. The basic circle represents continuity in movement, revolving from one idea to another. Within the image is an African American child reading a book. The five main religious symbols below the image of the child represent nonsectarianism. The superimposed pyramid symbolizes both stength and Atlanta University, the award’s headquarters when the seal was designed. At the apex of the pyramid is a dove, symbolic of peace. The rays shine toward peace and brotherhood. The Coretta Scott King Book Awards seal image and award name are solely and exclusively owned by the American Library Association. -

INSIDE Diahann Carroll, Oscar-Nominated

TPA TEXAS PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATION This paper can www.TheAustinVillager.com be recycled Vol. 47 No. 21 Phone: 512-476-0082 E mail: [email protected] October 11, 2019 Diahann Carroll, Oscar-Nominated, INSIDE Pioneering Black Actress, Passes By Nekesa Mumbi Moody | AP Entertainment Writer Jags to face stiff competition against old foe. See LBJ RAPPIN’ Page 2 Tommy Wyatt AISD SHOULD RETURN OUR TAX MONEY! J. Stanislaus encourages African Many of you have gone Americans to join to the AISD community the pilot ranks. meeting to learn that the See MISSION School District Trustees Page 5 have made a decision to close most of the schools in the minority communities. These historic schools is where most of our children have received their basic education. These schools Community advocate have served our communi- seeks to revive ties well. the 53rd District. Now these schools are See CANTU being thrown out with the Page 6 bath water without any concern for these historic Bertha Sadler contributions. These Means Young schools were named for some of our most Women’s respected citizens who Leadership worked hard to see that our communities were Academy to well served. In exchange Close in 2023 for their service, many schools and public by Carolyn Jones buildings were named in VILLAGER Columnist their honor. These public (VILLAGER) - If Ber- buildings and other tha Sadler Means was memorials is what we not physically present in used to educate our the cafeteria of the children on our history school named in her and service to the honor when AISD offi- community. -

Anthem: Social Movements and the Sounds of Solidarity in the African Diaspora

Anthem: Social Movements and the Sounds of Solidarity in the African Diaspora Shana L. Redmond 2014 New York University Press, New York and London _____________________________________________________________ What if you had a nation but not a country? This is what many people of African descent felt in their day-to-day lives in the Americas and in colonial Africa. Their nationality was defined by the colour of their skin. They were Blacks, Negros, les noirs or los morenos. The book “Anthem: Social Movements and the Sounds of Solidarity in the African Diaspora” explores how this nationality without a nation found a voice through social movements and their “national” anthems. Shana L. Redmond, a former musician and labour organizer currently teaching at the University of California Los Angeles, chooses to explore six songs and their associated social movements. The book proceeds chronologically, beginning with the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) founded in Jamaica by Marcus Garvey and Amy Ashwood. Set up to protect Africans around the world, the UNIA used all the trappings of a nation. It had a constitution, a social order, politics, uniforms and an anthem. An issue regarding the UNIA’s international status the author highlights is that “[t]he collective questioned for example, if meetings were to culminate in rousing renditions of the national anthem, should it be ‘God Save the King’ or ‘The Star Spangled Banner?’” (pg 24). The organization chose the song “Ethiopia” written in 1918 by Benjamin E. Burrell and Arnold J. Forde as its anthem. The lyrics “Ethiopia, land of our fathers” and “[o]f the red, the black and the green” pays homage to ideals of the UNIA to eradicate Western colonialism from Africa. -

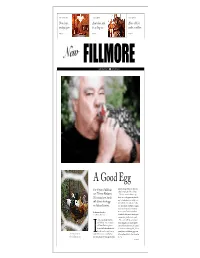

The New Fillmore

RETAIL REPORT FOOD & DRINK REAL ESTATE New shops, A new bar, and Home sells for medspa open it’s a long one under a million PAGES 5 - 7 PAGE 10 PAGE 14 New FILLMORE SAN FRANCISCO ■ AUGUST 2008 A Good Egg For 40 years, Phil Dean and drives along Golden Gate Park as he makes his way back to Fillmore Street. was Fillmore Hardware. He retired two and a half years ago, He’s retired now, but he but he’s never really gotten away from the neighborhood where he worked for most still delivers fresh eggs of his adult life. As he looks for a parking on Friday afternoon. space near Fillmore and Pine, he can glance out the window and see his fi ngerprints B B K R on nearly every Victorian on the block T R — lumber he sold, paint he mixed, repairs made according to advice he dispensed. ’ on a Friday afternoon, For an hour on Friday afternoon, just and Phil Dean, longtime manager before closing time, he’s back behind the of Fillmore Hardware, gets into counter of the hardware store, still greeting his truck in Pacifi ca and makes the customers and occasionally giving advice or drive he’s made so many times: up cutting keys — and delivering eggs, some ISkyline Drive, onto the Great Highway, of them gathered from his henhouse earlier S B past Ocean Beach. He turns right on Fulton that day. TO PAGE 8 4 LOCALS NEIGHBORHOOD NEWS Good Riddance, Say Locals, as Redevelopment Ends B D G “In the early days,” said executive di- But by this time, the African American destroyed a community, a way of life.” rector Fred Blackwell, “there is much that community had had enough. -

None of This Would Have Ever Happened If You Had Just Given an Oscar to Jennifer Lopez

NONE OF THIS WOULD HAVE EVER HAPPENED IF YOU HAD JUST GIVEN AN OSCAR TO JENNIFER LOPEZ By Tony Meneses Characters: Hugo Omar Nigel Elijah Yosef (all gay men of color in their 30’s/40’s) Setting: The last recorded Oscar party in gay history Time: February 9th, 2020 Wine. Charcuterie. Fresh fruit that no one’s eating. YOSEF. 1970? ELIJAH. ... Maggie Smith. NIGEL. Good one. YOSEF. 1991. ELIJAH Kathy Bates. HUGO. Also great. YOSEF. 1965! ELIJAH. Julie Andrews. NIGEL. (To Hugo.) Too easy. YOSEF 19... 46? ELIJAH. Joan fucking Crawford. NIGEL. HUGO. Oh my god! Yes ma-ma! NIGEL. That might actually be my favorite one. Mildred Pierce, can’t beat that. HUGO. What! Over Vivien Leigh, Ingrid Bergman, MERYL!?! 1 NIGEL. I stand by my decree. ELIJAH. Give me Elizabeth Taylor any day! YOSEF. 2002? In an instant it all goes quiet. NIGEL. ... What did you just say? YOSEF. 2002. Who won Best Actress in 2002? HUGO. Girl. Are you kidding? NIGEL. Oh god. She’s not. YOSEF. I’m not the biggest awards show gay, I’m sorry. HUGO. Who invited him again? ELIJAH. (Very serious.) 2002. That’s what you’re asking, Yosef? Two thousand, and two? YOSEF. Yes? ELIJAH. ... Halle Berry. Halle Berry won the Oscar that year. YOSEF. Oh. Isn’t that a good thing? We love Halle Berry. Don’t we? NIGEL. What kind of a question is that! 2 HUGO. You’re going to have to leave. ELIJAH. Halle Berry was—and remains to this day—the only woman of color to ever win the Academy Award for Best Actress. -

SEASON Ideas, and World-Renowned Artists from All from the Heart! Section C $20 Corners of the Planet Eager to Share Joy- Senior, Student & Youth Discounts Available

HEADLINERS ON THE Membership Welcome to NEW HAVEN GREEN has great benefits! Members receive special benefits for New Haven Memberships are a great way Green concerts including meet-and-greet Festival 2012! to support the Festival while opportunities, hospitality, and reserved seating! enhancing your experience. Five Great Reasons to Become The International Festival of Arts & Ideas is SING THE TRUTH! a Festival Member: FESTIVAL 2012 ANGELIQUE KIDJO, 1. Advance & Discount Tickets a 15-day extravaganza of performing arts DIANNE REEVES & 2. Special discounts at local and dialogues: a place to tickle your senses, LIZZ WRIGHT shops and restaurants engage your mind, find inspiration, and 3. Opportunities to mix and mingle with Festival Artists JUNE 16-30 JUNE 16 (7PM) FREE and fellow members take off on an adventure. A dazzling evening of song that 4. VIP Hospitality on the New Haven Green honors the music and spirit of great 5. Concierge Ticketing at the Supporting member level or women in jazz, folk, r&b, gospel, and the blues. Featuring the higher! music of Miriam Makeba, Odetta, Billy Holiday, and Lauryn Hill, as well as original music by Kidjo, Reeves, and Wright. FOR MORE INFORMATION AND TO JOIN TODAY, GO TO WWW.ARTIDEA.ORG/MEMBERSHIP ASPHALT ORCHESTRA JUNE 17 (7PM) FREE A one-of-a-kind street marching band that brings ambitious music to the masses in an exciting, take- Tickets over-the-crowd performance. Featuring music from the likes of Frank Zappa and Björk, with choreography by Susan Marshall. ON SALE Member Tickets NOW THE CAROLINA MEMBER PRE-SALE (BEFORE APR 15): Regular Premium CHOCOLATE DROPS $25 $35 APR 15 THROUGH THE FESTIVAL: JUNE 23 (7PM) FREE $30 Regular $40 Premium The Grammy-nominated Carolina Different pricing applies for Mark Morris Dance Group—see below. -

(Pdf) Download

accompanists one by one. The standard “Little Girl The album takes off with a floating 12/8 groove for Blue” is a beautiful duet with piano. “Driva Man” was “Talkin’ to the Sun”. Rodney Jordan‘s high-position one of Lincoln’s powerful performances on the We bass strumming underscores “Another World”, Insist! Freedom Now Suite (Candid, 1960) with Max a highlight with great texture, with Kevin Bales Roach. The voice and percussion duet has quite a rendering a muted piano string solo. Percussionist different feeling here, the “crack of the whip” not as Marlon Patton produces a range of tones throughout heavy and the message without the same urgency. In the album—what’s that? A rain stick? Scraps of metal? the original album notes, A. Philip Randolph is quoted “The River” flows, revisiting the textural approach and Love Having You Around regarding “America’s unfinished revolution”. The some free improvisation with guest Kebbi Williams on Abbey Lincoln (HighNote) Aminata Moseka: An Abbey Lincoln Tribute revolution was in a different place in 1980, but still alto saxophone. “Learning How to Listen” is a great Virginia Schenck (s/r) unfinished. “Throw It Away” is probably best known as song with a rubato opening developing into a swinging by Anders Griffen the haunting opener on A Turtle’s Dream (Verve, 1994); affair. “Caged Bird” offers a reading of Maya Angelou’s each version has its own mood but this one has its own poem as well as the Abbey Lincoln song. The former is The atmosphere is hushed with anticipation. The vitality.