Awareness, Solipsism and First-Rank Symptoms in Schizophrenia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leibniz, Bayle and the Controversy on Sudden Change Markku Roinila (In: Giovanni Scarafile & Leah Gruenpeter Gold (Ed.), Paradoxes of Conflicts, Springer 2016)

Leibniz, Bayle and the Controversy on Sudden Change Markku Roinila (In: Giovanni Scarafile & Leah Gruenpeter Gold (ed.), Paradoxes of Conflicts, Springer 2016) Leibniz’s metaphysical views were not known to most of his correspondents, let alone to the larger public, until 1695 when he published an article in Journal des savants, titled in English “A New System of the Nature and Communication of Substances, and of the Union of the Soul and Body” (henceforth New System).1 The article raised quite a stir. Perhaps the most interesting and cunning critique of Leibniz’s views was provided by a French refugee in Rotterdam, Pierre Bayle (1647−1706) who is most famous for his Dictionnaire Historique et Critique (1697). The fascinating controversy on Leibniz’s idea of pre-established harmony and a number of other topics lasted for five years and ended only when Bayle died. In this paper I will give an overview of the communication, discuss in detail a central topic concerning spontaneity or a sudden change in the soul, and compare the views presented in the communication to Leibniz’s reflections in his partly concurrent New Essays on Human Understanding (1704) (henceforth NE). I will also reflect on whether the controversy could have ended in agreement if it would have continued longer. The New System Let us begin with the article that started the controversy, the New System. The article starts with Leibniz’s objection to the Cartesian doctrine of extension as a basic way of explaining motion. Instead, one should adopt a doctrine of force which belongs to the sphere of metaphysics (GP IV 478). -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Eternity and Immortality in Spinoza's Ethics

Midwest Studies in Philosophy, XXVI (2002) Eternity and Immortality in Spinoza’s Ethics STEVEN NADLER I Descartes famously prided himself on the felicitous consequences of his philoso- phy for religion. In particular, he believed that by so separating the mind from the corruptible body, his radical substance dualism offered the best possible defense of and explanation for the immortality of the soul. “Our natural knowledge tells us that the mind is distinct from the body, and that it is a substance...And this entitles us to conclude that the mind, insofar as it can be known by natural phi- losophy, is immortal.”1 Though he cannot with certainty rule out the possibility that God has miraculously endowed the soul with “such a nature that its duration will come to an end simultaneously with the end of the body,” nonetheless, because the soul (unlike the human body, which is merely a collection of material parts) is a substance in its own right, and is not subject to the kind of decomposition to which the body is subject, it is by its nature immortal. When the body dies, the soul—which was only temporarily united with it—is to enjoy a separate existence. By contrast, Spinoza’s views on the immortality of the soul—like his views on many issues—are, at least in the eyes of most readers, notoriously difficult to fathom. One prominent scholar, in what seems to be a cry of frustration after having wrestled with the relevant propositions in Part Five of Ethics,claims that this part of the work is an “unmitigated and seemingly unmotivated disaster.. -

Identity, Personal Continuity, and Psychological Connectedness Across Time and Over

1 Identity, Personal Continuity, and Psychological Connectedness across Time and over Transformation Oleg Urminskyi, University of Chicago University of Chicago, Booth School of Business Daniel Bartels, University of Chicago University of Chicago, Booth School of Business Forthcoming, Handbook of Research on Identity Theory in Marketing 2 ABSTRACT: How do people think about whether the person they’ll be in the future is substantially the same person they’ll be today or a substantially different, and how does this affect consumer decisions and behavior? In this chapter, we discuss several perspectives about which changes over time matter for these judgments and downstream behaviors, including the identity verification principle (Reed et al. 2012) — people’s willful change in the direction of an identity that they hope to fulfill. Our read of the literature on the self-concept suggests that what defines a person (to themselves) is multi-faceted and in almost constant flux, but that understanding how personal changes relate to one’s own perceptions of personal continuity, including understanding the distinction between changes that are consistent or inconsistent with people’s expectations for their own development, can help us to understand people’s subjective sense of self and the decisions and behaviors that follow from it. 3 A person’s sense of their own identity (i.e., the person’s self-concept) plays a central role in how the person thinks and acts. Research on identity, particularly in social psychology and consumer behavior, often views a person’s self-concept as a set of multiple (social) identities, sometimes characterized in terms of the category labels that the person believes apply to themselves, like “male” or “high school athlete” (Markus and Wurf 1987). -

Mind Body Problem and Brandom's Analytic Pragmatism

The Mind-Body Problem and Brandom’s Analytic Pragmatism François-Igor Pris [email protected] Erfurt University (Nordhäuserstraße 63, 99089 Erfurt, Germany) Abstract. I propose to solve the hard problem in the philosophy of mind by means of Brandom‟s notion of the pragmatically mediated semantic relation. The explanatory gap between a phenomenal concept and the corresponding theoretical concept is a gap in the pragmatically mediated semantic relation between them. It is closed if we do not neglect the pragmatics. 1 Introduction In the second section, I will formulate the hard problem. In the third section, I will describe a pragmatic approach to the problem and propose to replace the classical non-normative physicalism/naturalism with a normative physicalism/naturalism of Wittgensteinian language games. In subsection 3.1, I will give a definition of a normative naturalism. In subsection 3.2, I will make some suggestions concerning an analytic interpretation of the second philosophy of Wittgenstein. In the fourth section, I will propose a solution to the hard problem within Brandom‟s analytic pragmatism by using the notion of the pragmatically mediated semantic relation. In the fifth section, I will make some suggestions about possible combinatorics related to pragmatically mediated semantic relations. In the sixth section, I will consider pragmatic and discursive versions of the mind-body identity M=B. In the last section, I will conclude that the explanatory gap is a gap in a pragmatically mediated semantic relation between B and M. It is closed if we do not neglect pragmatics. 2 The Hard Problem The hard problem in the philosophy of mind can be formulated as follows. -

Science, Subjectivity & Reality

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Science and Religion Dialogue Prints Journal of Consciousness Exploration & Research| April 2016 | Volume 7 | Issue 4 | pp. 333-336 333 Pereira, C. & Reddy, J. S. K., On Science & Phenomenology in Consciousness Studies Perspective Science, Subjectivity & Reality * Contzen Pereira & J. S. K. Reddy Abstract In this paper, we argue on the ability of science to capture the true subjective experience of life, blinded within the limits of its reductionist approaches. With this approach, even though science can explain well the physics behind the objective phenomenon, it fails fundamentally in understanding the various aspects associated with the biological entities. In this sense, we are skeptical to the present approach of science and calls out for a more fundamental theory of life that considers not only the objectivity aspect of a biological entity but also the subjective experience as well. It raises questions as to what does it takes to develop a new science from a subjective standpoint. Key Words: Science, subjectivity, reality, cosmos, peripersonal space. Modern science is based on the principle “Give us one free miracle and we’ll explain the rest.” The one free miracle is the appearance of all the matter and energy in the universe and all the laws that govern it from nothing, in a single instant - Terrence McKenna The Cosmos showers the experience of life graced by an enigmatic subject grounded in an objective fabric (or biological structure). The extent of the subjective experience is in a way bounded by the limitations of an objective fabric. -

The No-Self Theory: Hume, Buddhism, and Personal Identity Author(S): James Giles Reviewed Work(S): Source: Philosophy East and West, Vol

The No-Self Theory: Hume, Buddhism, and Personal Identity Author(s): James Giles Reviewed work(s): Source: Philosophy East and West, Vol. 43, No. 2 (Apr., 1993), pp. 175-200 Published by: University of Hawai'i Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1399612 . Accessed: 20/08/2012 03:38 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Hawai'i Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Philosophy East and West. http://www.jstor.org THE NO-SELF THEORY: HUME, BUDDHISM, AND JamesGiles PERSONAL IDENTITY The problem of personal identity is often said to be one of accounting for Lecturerin Philosophy what it is that gives persons their identity over time. However, once the and Psychologyat Folkeuniversitetet problem has been construed in these terms, it is plain that too much has Aalborg,Denmark already been assumed. For what has been assumed is just that persons do have an identity. To the philosophers who approach the problem with this supposition already accepted, the possibility that there may be no such thing as personal identity is scarcely conceived. As a result, the more fundamental question-whether or not personal identity exists in the first place-remains unasked. -

Aristotelian Habitus and the Power of the Embodied Self: Reflections on the Insights Gained from the Fakirs in Bangladesh

23 Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology. Volume 17, Number 2. July 2020. Aristotelian Habitus and the Power of the Embodied Self: Reflections on the Insights Gained from the Fakirs in Bangladesh Mohammad Golam Nabi Mozumder1, Abstract: This article traces back classical Greek and Medieval meanings of habitus to show that Bourdieu’s redefinition of habitus discarded a seminal feature of Aristotelian habitus—the power of radically transforming the self at will. I elaborate how the practices of purposefully training the embodied self remains marginalized in Pierre Bourdieu’s re-conceptualization of habitus. Examining Aristotle’s habitus, this paper brings back the focus on the long-neglected insight of the power of deliberately (re)training the self in constructing a heterodox but ethical way of being and socializing. As an example, I refer to the Fakirs in current Bangladesh, who cultivate antinomian life-practices. The main argument of the paper is that habitus in Bourdieu’s formulations is less suitable than Aristotle’s in analysing the praxis of the Fakirs. I suggest that instead of sticking to a universal conceptualization of habitus, sociologists should consider with equal importance both models of habitus articulated by Aristotle and Bourdieu. Doing that could benefit contemporary sociology in two ways: First, Aristotle’s conceptualization of habitus is an important tool in identifying the sociological importance of the praxis of marginalized groups, e.g., Fakirs in Bangladesh; and second, extending the focus of a key sociological concept, i.e., habitus, addresses the apparent disconnect between the wisdom of heterodox practitioners in the Global South and dominant social theories built upon the analyses of European and American social traditions. -

Hegel and Aristotle

HEGEL AND ARISTOTLE ALFREDO FERRARIN Boston University published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, vic 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org © Alfredo Ferrarin 2001 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2001 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Baskerville 10.25/13 pt. System QuarkXPress™ 4.04 [AG] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Ferrarin, Alfredo, 1960– Hegel and Aristotle / Alfredo Ferrarin. p. cm.–(Modern European philosophy) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-521-78314-3 1. Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich, 1770–1831. 2. Aristotle – Influence. I. Title. II. Series. B2948 .F425 2000 193–dc21 00-029779 ISBN 0 521 78314 3 hardback CONTENTS Acknowledgments page xiii List of Abbreviations xv Introduction 1 § 1. Preliminary Notes 1 § 2. On the Object and Method of This Book 7 § 3. Can Energeia Be Understood as Subjectivity? 15 part i the history of philosophy and its place within the system 1. The Idea of a History of Philosophy 31 § 1. The Lectures on the History of Philosophy: Editions and Sources 31 § 2. -

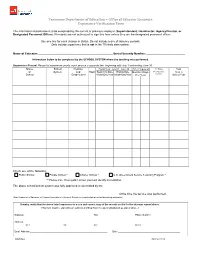

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

Brains and Behavior Hilary Putnam

2 Brains and Behavior Hilary Putnam Once upon a time there was a tough- ism appeared to exhaust the alternatives. minded philosopher who said, 'What is all Compromises were attempted ('double this talk about "minds", "ideas", and "sen- aspect' theories), but they never won sations"? Really-and I mean really in the many converts and practically no one real world-there is nothing to these so- found them intelligible. Then, in the mid- called "mental" events and entities but 1930s, a seeming third possibility was dis- certain processes in our all-too-material covered. This third possibility has been heads.' called logical behaviorism. To state the And once upon a time there was a nature of this third possibility briefly, it is philosopher who retorted, 'What a master- necessary to recall the treatment of the piece of confusion! Even if, say, pain were natural numbers (i.e. zero, one, two, perfectly correlated with any particular three ... ) in modern logic. Numbers are event in my brain (which I doubt) that identified with sets, in various ways, de- event would obviously have certain prop- pending on which authority one follows. erties-say, a certain numerical intensity For instance, Whitehead and Russell iden- measured in volts-which it would be tified zero with the set of all empty sets, senseless to ascribe to the feeling of pain. one with the set of all one-membered sets, Thus, it is two things that are correlated, two with the set of all two-membered not one-and to call two things one thing sets, three with the set of all three-mem- is worse than being mistaken; it is utter bered sets, and so on.