Spring 2017, Volume 36.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quicksilver Deposits of Steens Mountain and Pueblo Mountains Southeast Oregon

Quicksilver Deposits of Steens Mountain and Pueblo Mountains Southeast Oregon GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 995-B A CONTRIBUTION TO ECONOMIC GEOLOGY QUICKSILVER DEPOSITS OF STEENS MOUNTAIN AND PUEBLO MOUNTAINS, SOUTHEAST OREGON By HOWEL WILLIAMS and ROBERT R. The object of this survey was to examine the quicksilver deposits with the hope of locating large tonnages of low-grade ore. The deposits occur in the south-central part of Harney County and are more than 100 miles from either Burns, Oreg., or Winuemucca, Nev., the nearest towns. The region is sparsely settled by stockmen; Fields, Denio, and Andrews are the only settlements. The range consisting of Steens Mountain and Pueblo Mountains is a dissected fault block, 90 miles long in a north-south direction and as much as 25 miles wide, tilted gently to the west. Pre-Tertiary rnetarnorphic and plutonic rocks occur at the southern end, but most of the block consists of Pliocene volcanic rocks. The major boundary faults on the east side of the range are concealed by alluvium. Minor northwestward-trending faults branch from them, their throws diminish ing toward the crest of the range; other minor fractures occur near, and parallel to, the mountain front. The quicksilver lodes were formed in and along these subsidiary fractures. The lodes occur in a more or less continuous belt just west of the eastern front of the range. They are steeply dipping and arranged in subparallel clusters, commonly standing out as resistant siliceous ribs against the softer kaolinized rocks that flank them. The lodes were formed in two hydrothermal stages, the first producing the reeflike masses of chalcedony and quartz with their halos of limonitic and calcitic clays and the second introducing silica and barite along with sulfides of iron, copper, and mercury. -

Geothermal Investigation of the Alvord Valley, Southeast Oregon

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1976 Geothermal investigation of the Alvord Valley, southeast Oregon John Gladden Cleary The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cleary, John Gladden, "Geothermal investigation of the Alvord Valley, southeast Oregon" (1976). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2442. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2442 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEOTHERMAL INVESTIGATION OF THE ALVORD VALLEY, SOUTHEAST OREGON By John G. Cleary B.A., Dartmouth College, 1974 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1976 Approved by; Chairman, Board of Examiners DeaoT Gradua-^^hool /Jy /f 7^ UMI Number: EP34784 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI EP34784 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Plant Communities of the Steens Mountain Subalpine Grassland and Their Relationship to Certain En

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF John William Mairs for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography presented on April 29, 1977 Title: PLANT COMMUNITIES OF THE STEENS MOUNTAIN SUBALPINE GRASSLAND AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO CERTAIN EN- VIRONMENTAL ELEMENTS Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy Robert E. Frenkel Plant communities in a 3.5 km2area along the summit ridge of Steens Mountain, Harney County in southeastern Oregon are identified. The character of winter snow deposi- tion and spring melt in this subalpine zone is a major fac- tor in producing the vegetation pattern.Past domestic grazing, topography, wind pattern, climate, soil depth and soil moisture availability are related to the present vege- tation mosaic. Computer-assisted vegetation ordination of 278 tran- sect-located sample units using SIMORD and tabular plant association analysis of 346 areally-located releves using PHYTO were applied complementarily. Aided by the interpre- tation of true-color aerial photography (1:5000), this analysis revealed and mapped 12 plant communities and one additional combination community named after dominant species. After comparison of four selected similarity indexes commonly used in vegetation ordination analysis, Sorensen's modified similarity index was chosen as best for interpretation of stand groupings in the study data. The general vernal snow cover recession pattern was verified with LANDSAT-1 digital data representations. Plant communities associated with snow deflation, or crest, areas are Erigeron compositus-Astragalus whitneyi, -

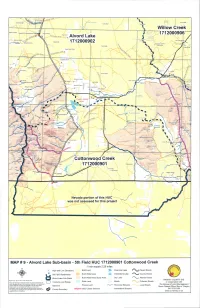

Alvord Lake Toerswnq Ihitk-Ul,.N Itj:Lnir

RtflOP' nt T37S Rt3F T37SR36E T37S R3275E 137S R34E TITStSE BloW Pour Willow Creek Babes Canyor Relds BIM Adrnirtistrative SiteFjel NeSs Airstrip / 41 171 2000906 Alvord Lake tOerswnq ihiTk-ul,.n itj:Lnir. Inokoul hluutte\ McDade Ranch 1712000902 I cvwr Twin Hot Spn Os Wilhlants Canyon , ,AEyy.4N seiralNo WARM APRI '738SR37E rIBS R3BE R38E Lower Roux Place err hlomo * / Oaterkirk Rartch - S., Rabbit HOe Mine 7,g.hit 0 Ptace '0 Arstnp 0 0 Ainord Vafley Lavy1ronrb P -o Rriaia .....c I herbbrrr RarrCh C _: 9S R34E Trout Creek CAhn '5- T39S R36E N Oleacireen Place T395 R37F Cruallu Canyon -1 Oleachea Pass T39S R38E \ Stergett Cabot Trout Creek Ranch ty Silvey Adrian Place' Wee Pole Canyon C SPRiNG, WHITEHORSE RANCH LN Pueblo Valley 4040 S Center Ridg Will, reek Pt cLean Cabin orgejadowo Gob 0810 WEIi Reynolds Ranch Owens Randr / I p labor Mocntai /1 °ueblo Mountain A'ir.STWLL Neil Pei S 'i-nWt Mahogany Ri.ge ,haaesot, uSGi, Pee: enn;s *i;i train ' 6868 4 n*a.asay Holloway T4OS R34E T4OS R35E I 1405 6E T405 R37E 'I 14'R38E / i.l:irintoi "Van Hone Basin' Colony Ranch 0 U Lithe Windy Pass z SChrERRYSPR1N. 0 I 1* RO4 - - 'r Denio Basin A' tuitdIhSPIhlNn% ()Conne eme Cottonwood Creek ie;. r' Gller Cabin T4IS R37E L,aticw P ',ik 1712000901 Grassy Basin BLAiRO tih'dlM P4 IS R34E Ago 141S R36E Lung Canyon Ii Middle Canyon Oecio Cemetery East B. ring Corral Canyon ento Nevada portion of this HUC was not assessed for this project MAP # 9 - Alvord Lake Sub-basin - 5th Field HUC 1712000901 Cottonwood Creek 1 inch equals 2.25 miles High and Low Elevations BLM Land Perennial Lake Paved Roads 5th Field Watersheds BLM Wilderness - Intermittent Lake County Roads S Alvord Lake Sub-Basin BLM Wilderness Study Area Dry Lake Arterial Roads HARNEY COUNTY GIS Prnpaeod by: Bryca Mcrnz Dare: Momlu 2006 State Land Marsh "_. -

Early and Middle Holocene Archaeology in the Northern Great Basin: Dynamic Natural and Cultural Ecologies

Early and Middle Holocene Archaeology in the Northern Great Basin: Dynamic Natural and Cultural Ecologies by Dennis L. Jenkins, Thomas J. Connolly, and C. Melvin Aikens The primary questions addressed in this chapter— begin to address even the most basic issues. Yet, here and in the volume as a whole—include: “were humans at the very foundation of our research, archaeologists present in the Northern Great Basin during Terminal have often made too little effort to be consistent Pleistocene times?” and “what is our current within the discipline. In this volume, we attempt to understanding of changing cultural and ecological add impetus to an important change in the reporting regimes in the Northern Great Basin during Early and and use of radiocarbon dates in Northern Great Basin Middle Holocene times?” This introductory chapter research that is long overdue. We advocate the addresses the first question in methodological terms at primary use of calibrated radiocarbon ages when the outset, and later we offer in more substantive discussing time, a convention used throughout this terms our current understanding of the key issues volume, rather than continuing to employ presented in the following papers. To deal with the conventional radiocarbon ages. second question, which is much broader, we Radiocarbon dating has undoubtedly been the summarize in a general way the contributions of the single most important method of age determination volume as a whole. It is necessary to begin, however, employed in the field of archaeology since its with preparatory discussions of the radiocarbon dating invention in 1950. But in the Northern Great Basin, as and obsidian hydration research methods and elsewhere, the radiocarbon chronology generally reporting protocols employed throughout this initial employed in regional synthetic and comparative chapter, and throughout the volume as a whole. -

Ore Bin / Oregon Geology Magazine / Journal

Vol. 22, No. 10 THE ORE.-BIN 97 October 1960 Portland, Oregon STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES Head Office: 1069 State Office Bldg., Portland 1, Oregon Telephone: CApitol 6-2161, Ext. 488 Field Offices 2033 First Street 239S. E. "H" Street Baker Grants Pass * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * BORON IN ALVORD VALLEY, HARNEY COUNTY, OREGON By F. W. Libbey * Introduction . The advent of the Space Age brought high-energy fuels into sharp focus. Boron compounds have offer ed promise as on important component of these fuels and have received much publ icity in this connection. Thus attention has been directed to possible new sources of boron even though no shortage of domestic sup pi i es can be foreseen at present. Around the turn of the present century borax was harvested commercially from crusts formed on the sur face of Alvord Volley, south of Alvord Lake, in southern Harney County, southeastern Oregon, just east of the famous Steens-Pueblo Mountains. In 1957-58 a minor boom developed in applications for prospecting permits on federal land in the gen eral vicinity of Alvord Lake basin. The present paper describes the conditions of boron occurrence in the basin and attempts to bring developments in the area up to date. In July, 1947, the author was in the basin locality and sampled the water of Hot Lake at one outlet; the assay returned 80 p. p. m. of B203. During the last week of August and the first week of September, 1960, the area was revisited and thermal springs sampled as described in the following text. -

Aquisition of a Terrestrial Laser Scanning System for Polar Research

ACQUISITION OF A TERRESTRIAL LASER SCANNING SYSTEM FOR POLAR RESEARCH Submitted to Office of Polar Programs, 25 January 2007 C. Meertens, Bjorn Johns and David Phillips, UNAVCO Phillip Kyle, New Mexico Tech (Optech ILRIS-3D) Taylor Glacier (left), with visible stream channels, ows from the East Antarctic plateau and terminates in Lake Bonney. (Photo: Dennis Kenley.) Project Summary: Advances in Terrestrial Laser Scanner (TLS) technology and recent compelling applications of TLS to Earth science research represent new and exciting opportunities for the polar geoscience community. TLS technology is based on Light Distance and Ranging (LiDAR) and is also referred to as ground-based LiDAR or tripod LiDAR. The primary capability of TLS is the generation of high resolution 3-dimensional maps and images of surfaces and objects over scales of meters to kilometers with centimeter or sub-centimeter precision. This allows for high accuracy mapping as well as the determination of surface changes over time via repeated measurements. The incorporation of GPS measurements provides accurate georeferencing of TLS data in an absolute reference frame. The addition of digital photography yields photorealistic 3D images. Moreover, TLS systems are portable and therefore suitable for a wide spectrum of user applications in polar environments. This proposal is for the acquisition of a TLS system and associated digital photography equipment, TLS software and deployment equipment optimized for use in Antarctic and Arctic regions. This TLS system will be a shared resource managed by the UNAVCO Facility and integrated into UNAVCO’s ongoing support for NSF Office of Polar Programs (OPP) projects. Considering the expense of TLS equipment and the expertise needed for successful operation, this approach represents the most cost effective means of making this technology accessible to the OPP research community. -

Collaborative Research MRI: Acquisition of Terrestrial Laser Scanning Systems for Earth Science Research

Collaborative Research MRI: Acquisition of Terrestrial Laser Scanning Systems for Earth Science Research Submitted to EAR Major Research Instrumentation 22 January 2009 M. Meghan Miller, Charles Meertens and David Phillips, UNAVCO Charlie Rubin, Lisa Ely, Beth Pratt-Sitaula, Central Washington University RESESS Intern Emanuelle Feliciano Bonilla operating a UNAVCO Optech ILRIS-3D scanner at Bijou Creek Colorado. A UNAVCO pool GPS RTK system is mounted on the scanner. GPS equipment are available from UNAVCO and are therefore not requested in this proposal. A high resolution digital camera calibrated to the TLS can be mounted where the GPS is mounted in this photo. Project Summary: Advances in Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS) technology and recent compelling applications of TLS to Earth science research represent new and exciting opportunities for the Earth science community. TLS technology is based on Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) and is also referred to as ground-based LiDAR or tripod LiDAR. The primary capability of TLS is the generation of high resolution 3-dimensional maps and images of surfaces and objects over scales of meters to kilometers with centimeter or sub-centimeter precision. This allows for high accuracy mapping as well as the determination of surface changes over time via repeated measurements. The incorporation of GPS measurements provides accurate georeferencing of TLS data in an absolute reference frame. The addition of digital photography yields photorealistic 3D images. TLS systems are portable and therefore suitable for a wide spectrum of user applications in many different environments. This proposal is for the acquisition of two TLS instrumentation systems and associated peripherals, digital photography equipment, software and deployment equipment optimized to support Earth science research. -

2015 FRANCES PELZMAN LISCIO About Our Cover Artist Frances Pelzman Liscio SUMMER 2015

SUMMER 2015 "LOVE" ©2015 FRANCES PELZMAN LISCIO about our cover artist Frances Pelzman liscio SUMMER 2015 Poem “Walking on Water” by Mark Jarman non-Fiction “i Heard notHing once” by Gina Williams non-Fiction “Personal accounting” by Lea Page Poem “comPlementarity” and “Wait” by Cyril Wong Fiction “radia's carPet” by Leila Aboulela non-Fiction “accePtance” by Joyce Lott artWork “biograPHical sketcH” artwork by Jacquelyn Martino intervieW intervieW WitH dr.ian Prattis by Melissa Studdard 2015 tiFeret Poem-a-tHon Poets: Ava Leavell Haymon Katherine Goodwin Philip Marley Kimberly Burnham Ambika Talwar Laura J Wolfe Bridget Nutting Louise Moriarty Catriona Knapman Maureen Kwiat Meshenberg Christine Donegan Segall Shannon S. Hyde Hazel Saville Tracy Brooks Jamie Hennick Udo Hintze >submit your Writing or ad SUMMER 2015 COVER ARTIST About our cover artist FRANCES PELZMAN LISCIO FRANCES PELZMAN LISCIO has had her work showcased in countless group and solo shows. Her work has been published in fine art, design and lifestyle blogs and magazines including Design Sponge, Traditional Home, Martha Stewart Living, Real Simple, Lucky, Elle Décor, and more and is included in hundreds of private collections, corporate offices and medical facilities. Her work has also graced CD and record albums, bookcovers, magazine covers, notecards, tea towels and Yoga wear. She lives and works in Montclair, New Jersey. Ms. Liscio holds a degree in printmaking, photography and illustration from Manhattanville College. She has studied printmaking with John Ross Sr., photography with Sean Kernan, Eva Rubenstein, Lisette Model, and John Loengard, digital darkroom and printing technologies with Jay Seldin, and botanical illustration with Deirdre Newman. -

North American Eagle Land Speed Trials Environmental Assessment

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management Burns District Office Andrews Resource Area Finding of No Significant Impact North American Eagle Environmental Assessment DOI-BLM-OR-B060-2012-0013-EA INTRODUCTION Andrews Resource Area, Burns District, has prepared an Environmental Assessment (EA) to analyze potential impacts of issuing a Special Recreation Permit (SRP) for the purpose of testing a land speed vehicle by North American Eagle, Inc. (herein after known as the "NAE"). The NAE submitted an operating plan of their proposed action to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Burns District, as part of an application to obtain a SRP to conduct land speed trials and activities. The proponent proposes to conduct this testing on Alvord Desert (Playa), Harney County, Oregon (See Map 1). This particular landform provides features uniquely suited to the Proposed Action including: an area of sufficient length for vehicle runs that could reach or exceed 600 miles per hour (mph); limited access points to the Playa, which is desirable for security and safety purposes; and soil conditions suited to this type of event. SUMMARY OF THE PROPOSED ACTION The Proposed Action is for the BLM to issue an SRP to NAE to conduct land speed tests on Alvord Desert Playa. The testing is to verify handling characteristics, aerodynamic characteristics and gather data to validate computer simulations created and tested by the NAE aerodynamics team. The project area encompasses a 12-mile length of “track” of Playa including several lanes of various widths and lengths and a private land two-track dirt access road that leads from East Steens County Road to the Playa, a ground support area and an area designated for the placement of timing equipment. -

Dust Devils: Structural Features, Dynamics and Climate Impact

This is a repository copy of Dust devils: structural features, dynamics and climate impact. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/140557/ Version: Published Version Article: Onishchenko, O., Fedun, V. orcid.org/0000-0002-0893-7346, Horton, W. et al. (2 more authors) (2019) Dust devils: structural features, dynamics and climate impact. Climate, 7 (1). 12. ISSN 2225-1154 https://doi.org/10.3390/cli7010012 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ climate Article Dust Devils: Structural Features, Dynamics and Climate Impact ∗ Oleg Onishchenko 1,†, Viktor Fedun 2, , Wendell Horton 3, Oleg Pokhotelov 1 and Gary Verth 4 1 Schmidt Institute of Physics of the Earth of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 123242 Moscow, B. Gruzinskaya 10-1, Russia; [email protected] (O.O.); [email protected] (O.P.) 2 Plasma Dynamics Group, Department of Automatic Control and Systems Engineering, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S13JD, UK 3 Space and Geophysical Laboratory at Applied Research Laboratory at the University of Texas (ARLUT), Austin, 78712, USA; [email protected] 4 Plasma Dynamics Group, School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Sheffield, Hicks building, Sheffield S3 7RH, UK; g.verth@sheffield.ac.uk * Correspondence: v.fedun@sheffield.ac.uk † Second address: Space Research Institute, 84/32 Profsouznaya Str., 117997 Moscow, Russia. -

Chipped Stone Crescents from America's

XML Template (2015) [12.3.2015–7:12am] [1–22] //blrnas3.glyph.com/cenpro/ApplicationFiles/Journals/SAGE/3B2/NAAJ/Vol00000/150003/APPFile/SG- NAAJ150003.3d (NAA) [PREPRINTER stage] Article North American Archaeologist 0(0) 1–22 Chipped stone ! The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: crescents from sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0197693115570286 America’s Far West: naa.sagepub.com Descriptive and geochemical analyses from the Northern Great Basin Nicholas P Jew and Amira F Ainis Department of Anthropology and Museum of Natural and Cultural History, University of Oregon, USA Pamela E Endzweig Museum of Natural and Cultural History, University of Oregon, USA Jon M Erlandson Museum of Natural and Cultural History and Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon, USA Craig Skinner Northwest Research Obsidian Studies Laboratory, USA Kelsey J Sullivan Museum of Natural and Cultural History, University of Oregon, USA Abstract Chipped stone crescents, Terminal Pleistocene and Early Holocene artifacts from North America’s Far West, are often found in surficial contexts as isolated finds, with many currently residing in private or museum collections with limited provenience information. Such collections have the potential to reveal metric and morphological data, and contribute to our understanding of the distribution and material source Corresponding Author: Nicholas P Jew, Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon, 1218 Condon Hall Eugene, OR 97403-1218, USA. Email: [email protected] XML Template (2015) [12.3.2015–7:12am] [1–22] //blrnas3.glyph.com/cenpro/ApplicationFiles/Journals/SAGE/3B2/NAAJ/Vol00000/150003/APPFile/SG- NAAJ150003.3d (NAA) [PREPRINTER stage] 2 North American Archaeologist 0(0) locations for this unique artifact type.