Third Letter to Lord Pelham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NRHA Derby Champions

NRHA Open Derby Champions & Reserve Champions Year Horse Sire Dam Rider Owner 1980 Champion Great Kelind Miss Great Pine Bennett Star Bar John Amabile Richard Greenberg, Reserve Champion Cassandra Cody Joe Cody Dudes Baby Doll Bob Loomis CChicago, T Fuller, IL Catasauqua, PA 1981 Champion Dry Gulch Dry Doc Miss Tough Steel Bill Horn Sid Griffith, Amlin, OH Reserve Champion Two Eyed Matador Two Eyed Beaver Countess Matador Bill Horn M. Gipson & B. McCauley, Mansfield, 1982 Champion Sheza Mardelle Dee Mardelle Dixon Smoke Jackie Terry Thompson Dr. Ronald Reserve Champion Sanditch Dude Bar Ditch Dude Misty Penny Bar Rick Weaver LynneHigginbotham, Jenkins, Batavia, Columbus, OH 1983 Champion How D Mae Bee Tee Jay Super Jack Skip Mae Montleon Doug Milholland Tom McFaddan, Reserve Champion Mr Superior Jac Hollywood Jac 86 Mission Jean Larry Rose RichardHazard, Greenberg,NE Chicago, IL 1984 Champion Ima Royal Shamrock Royal De King Ima Cold Bar Rocky Dare Debbie Clough, Co-Reserve Champion Paps Glo Doc Glo Miss Pap Cody Rocky Dare JoyceOsterville, Stinner, MA Co-Reserve Champion Athenas Cool Tone Doc Athena Cool Tone Dick Pieper HanesBreinigsville, Chatham, PA Aubrey, TX 1985 Champion Lassie Lady Jaquar Mr Jaguar Wallabys Lassie Terry Thompson Jim & Barb Mazziotta, Reserve Champion A Special Tee Spartan Specialty Miss Speedy Tee Doug Milholland SherdonStaten Island, Ranch, NY Omaha, NE 1986 Champion Vincents My Way Great Pine Hither Cody Bill Horn Henry Uvino, Islandia, Reserve Champion Im Not Trash Be Aech Enterprise Miss White Trash Bill Horn -

13.09.2018 Orcid # 0000-0002-3893-543X

JAST, 2018; 49: 59-76 Submitted: 11.07.2018 Accepted: 13.09.2018 ORCID # 0000-0002-3893-543X Dystopian Misogyny: Returning to 1970s Feminist Theory through Kelly Sue DeConnick’s Bitch Planet Kaan Gazne Abstract Although the Civil Rights Movement led the way for African American equality during the 1960s, activist women struggled to find a permanent place in the movement since key leaders, such as Stokely Carmichael, were openly discriminating against them and marginalizing their concerns. Women of color, radical women, working class women, and lesbians were ignored, and looked to “women’s liberation,” a branch of feminism which focused on consciousness- raising and social action, for answers. Women’s liberationists were also committed to theory making, and expressed their radical social and political ideas through countless essays and manifestos, such as Valerie Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto (1967), Jo Freeman’s BITCH Manifesto (1968), the Redstockings Manifesto (1969), and the Radicalesbians’ The Woman-Identified Woman (1970). Kelly Sue DeConnick’s American comic book series Bitch Planet (2014–present) is a modern adaptation of the issues expressed in these radical second wave feminist manifestos. Bitch Planet takes place in a dystopian future ruled by men where disobedient women—those who refuse to conform to traditional female gender roles, such as being subordinate, attractive (thin), and obedient “housewives”—are exiled to a different planet, Bitch Planet, as punishment. Although Bitch Planet takes place in a dystopian future, as this article will argue, it uses the theoretical framework of radical second wave feminists to explore the problems of contemporary American women. 59 Kaan Gazne Keywords Comic books, Misogyny, Kelly Sue DeConnick, Dystopia Distopik Cinsiyetçilik: Kelly Sue DeConnick’in Bitch Planet Eseri ile 1970’lerin Feminist Kuramına Geri Dönüş Öz Sivil Haklar Hareketi Afrikalı Amerikalıların eşitliği yolunda önemli bir rol üstlenmesine rağmen, birçok aktivist kadın kendilerine bu hareketin içinde bir yer edinmekte zorlandılar. -

Portrayals of Stuttering in Film, Television, and Comic Books

The Visualization of the Twisted Tongue: Portrayals of Stuttering in Film, Television, and Comic Books JEFFREY K. JOHNSON HERE IS A WELL-ESTABLISHED TRADITION WITHIN THE ENTERTAINMENT and publishing industries of depicting mentally and physically challenged characters. While many of the early renderings were sideshowesque amusements or one-dimensional melodramas, numerous contemporary works have utilized characters with disabilities in well- rounded and nonstereotypical ways. Although it would appear that many in society have begun to demand more realistic portrayals of characters with physical and mental challenges, one impediment that is still often typified by coarse caricatures is that of stuttering. The speech impediment labeled stuttering is often used as a crude formulaic storytelling device that adheres to basic misconceptions about the condition. Stuttering is frequently used as visual shorthand to communicate humor, nervousness, weakness, or unheroic/villainous characters. Because almost all the monographs written about the por- trayals of disabilities in film and television fail to mention stuttering, the purpose of this article is to examine the basic categorical formulas used in depicting stuttering in the mainstream popular culture areas of film, television, and comic books.' Though the subject may seem minor or unimportant, it does in fact provide an outlet to observe the relationship between a physical condition and the popular conception of the mental and personality traits that accompany it. One widely accepted definition of stuttering is, "the interruption of the flow of speech by hesitations, prolongation of sounds and blockages sufficient to cause anxiety and impair verbal communication" (Carlisle 4). The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 41, No. -

Magwitch's Revenge on Society in Great Expectations

Magwitch’s Revenge on Society in Great Expectations Kyoko Yamamoto Introduction By the light of torches, we saw the black Hulk lying out a little way from the mud of the shore, like a wicked Noah’s ark. Cribbed and barred and moored by massive rusty chains, the prison-ship seemed in my young eyes to be ironed like the prisoners (Chapter 5, p.34). The sight of the Hulk is one of the most impressive scenes in Great Expectations. Magwitch, a convict, who was destined to meet Pip at the churchyard, was dragged back by a surgeon and solders to the hulk floating on the Thames. Pip and Joe kept a close watch on it. Magwitch spent some days in his hulk and then was sent to New South Wales as a convict sentenced to life transportation. He decided to work hard and make Pip a gentleman in return for the kindness offered to him by this little boy. He devoted himself to hard work at New South Wales, and eventually made a fortune. Magwitch’s life is full of enigma. We do not know much about how he went through the hardships in the hulk and at NSW. What were his difficulties to make money? And again, could it be possible that a convict transported for life to Australia might succeed in life and come back to his homeland? To make the matter more complicated, he, with his money, wants to make Pip a gentleman, a mere apprentice to a blacksmith, partly as a kind of revenge on society which has continuously looked down upon a wretched convict. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Western Chorus Frog (Pseudacris Triseriata), Great Lakes/ St

PROPOSED Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Western Chorus Frog (Pseudacris triseriata), Great Lakes/ St. Lawrence – Canadian Shield Population, in Canada Western Chorus Frog 2014 1 Recommended citation: Environment Canada. 2014. Recovery Strategy for the Western Chorus Frog (Pseudacris triseriata), Great Lakes / St. Lawrence – Canadian Shield Population, in Canada [Proposed], Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series, Environment Canada, Ottawa, v + 46 pp For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including COSEWIC Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry (www.sararegistry.gc.ca). Cover illustration: © Raymond Belhumeur Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement de la rainette faux-grillon de l’Ouest (Pseudacris triseriata), population des Grands Lacs et Saint-Laurent et du Bouclier canadien, au Canada [Proposition] » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2014. All rights reserved. ISBN Catalogue no. Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. Recovery Strategy for the Western Chorus Frog 2014 (Great Lakes / St. Lawrence – Canadian Shield Population) PREFACE The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress within five years of the publication of the final document on the Species at Risk Public Registry. -

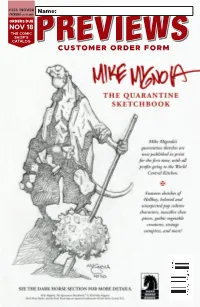

Customer Order Form

#386 | NOV20 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Nov20 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:23:12 AM Nov20 Ad DST Rogue.indd 1 10/8/2020 11:07:39 AM PREMIER COMICS HAHA #1 IMAGE COMICS 30 RAIN LIKE HAMMERS #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 CRIMSON FLOWER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 62 AVATAR: THE NEXT SHADOW #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 64 MARVEL ACTION: CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING 104 KING IN BLACK: BLACK KNIGHT #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-6 RED SONJA: THE SUPER POWERS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 126 ABBOTT: 1973 #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 158 Nov20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:24:32 AM COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE FEATURED ITEMS Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS I Breathed A Body #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS 1 Delicates TP l ONI PRESS l I Breathed A Body #1 AFTERSHOCK COMICS 1 The Cutting Edge: Devil’s Mirror #1 l TITAN COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS Knights of Heliopolis HC l TITAN COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Blade Runner 2029 #2 l TITAN COMICS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars Insider #200 l TITAN COMICS Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Comic Book Creator #25 l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Bloodshot #9 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Vagrant Queen Volume 2: A Planet Called Doom TP l VAULT COMICS Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. -

1407218430.Pdf (3.091Mb)

Welcome to 616! - A Marvel Comics fanfiction zine Table of Contents Young Avengers by Dorodraws – Young Avengers (Art) Featuring (deaged, reincarnated) Loki, America Chavez (Miss America), Tommy Shepherd (Speed), Kate Bishop (Hawkeye), Billy Kaplan (Wiccan) and Teddy Altman (Hulkling) Here In The Clouds by Brandnewfashion Here in the Clouds by Brandnewfashion - Captain Marvel “What are you doing up here?” Featuring Carol Danvers (Captain Marvel)/Peter Parker (Spider-man) Carol didn’t have to look over to see who the newcomer was. “Hi, Peter,” she greeted. Something With Wings by Elspethdixon – Avengers Said web-slinger slipped off his mask before sitting down next to the Featuring Jan van Dyne (The Wasp)/Hank Pym (Ant-man) blonde. “So.” “So?” Carol’s lips curved upwards into a smile. Smash by ScaryKrystal – Captain Marvel, She-Hulk (Art) Peter chuckled. “Are we really doing this again?” She shook her head. “I was just up here thinking.” Featuring Carol Danvers (Captain Marvel) & Jen Walters (She-Hulk) He nodded and they both looked out at the sight before them: New York always looked better at night. Manhattan was constantly bustling with Afternoon Stroll by Neveralarch – Hawkeye activity, but Queens never failed to provide a level of comfort to Peter: it Featuring Clint Barton (Hawkeye) & Kate Bishop (Hawkeye) was, after all, where he grew up. From the top of the abandoned warehouse that they were sitting on, they had a clear view of the Manhattan skyline, but By Hands and Heels by Lunik – Journey into Mystery the noises of the city were too far to be heard. Featuring Leah, (deaged, reincarnated) Loki & Thori the Hellhound Carol’s voice broke through his reverie. -

{PDF EPUB} Spider-Man: the Gathering of the Sinister Six By

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Spider-Man: The Gathering of the Sinister Six by Adam- Troy Castro The first of the Sinister Six trilogy of text novels by Adam-Troy Castro finds a sinister "Gentleman" gathering together the Sinister Six, but one of them-Mysterio is launching a deadly plot of his own against the acting community. I have to admit that this book did kind of pull the rug out from under me.4.1/5(24)Format: Mass Market PaperbackAuthor: Adam-Troy CastroImages of Spider-Man the Gathering of the Sinister Six by Adam-Tr… bing.com/imagesSee allSee all imagesSpider-Man: The Gathering of the Sinister Six: Castro ...https://www.amazon.com/Spider-Man- Gathering...A mysterious figure known only as The Gentleman gathers together Doc Ock, Mysterio, The Vulture, Electro and The Chameleon to form the Sinister Six. The sixth member is Pity, The Gentleman's mentally troubled, but no less lethal, henchperson. The true plan is for four of the Six to keep Spidey busy, while the other two conduct a robbery of a sort.3.8/5(23)Format: Audio CDAuthor: Adam-Troy CastroSpider-Man: The Gathering of the Sinister Six by Adam-Troy ...https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/377317The first of the Sinister Six trilogy of text novels by Adam-Troy Castro finds a sinister "Gentleman" gathering together the Sinister Six, but one of them-Mysterio is launching a deadly plot of his own against the acting community. I have to admit that this book did kind of pull the rug out from under me.4.1/5Ratings: 113Reviews: 8Pages: 309People also askWhen did the Sinister Six first appear in Spider - Man?When did the Sinister Six first appear in Spider - Man?The Sinister Six first appeared in The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #1 (January 1964). -

From the Files of the Museum

The Henry L. Ferguson Museum Newsletter Vol. 27, No. 1 • Spring 2012 (631) 788-7239 • P.O. Box 554 Fishers Island, NY 06390 • [email protected] • www.fergusonmuseum.org From the President Spring is well underway on Fishers Island as I write this new annual show featuring the artwork of Charles B. Fer- annual greeting on behalf of the Museum. After one of the guson. This promises to be one of our most popular shows mildest winters in my memory, spring has brought a strange and a great tribute to Charlie. We are also mounting a special mix of weather conditions with temperatures well into the exhibit that honors the wonderful legacy of gardens and par- 80s during March followed by chilly days in April and May. ties at Bunty and the late Tom Armstrong’s Hoover Hall and For those interested in phenology, the bloom time of many of Hooverness. We hope that all will come celebrate with us at our plants has been well ahead of schedule this year. The early our opening party on Saturday, June 30th, 5 to 7 p.m. bloom time raises questions regarding the first appearances of The Land Trust continues to pursue land acquisitions un- butterflies and other pollinators and the first arrivals of migra- der the able guidance of our Vice-President Bob Miller. One tory birds. Will these events coincide with bloom time as they of our recent projects is the management of Silver Eel Pre- have in the past or is the timing out of synch? It will be in- serve, a parcel of land that was purchased with open space teresting to track the timing of spring happenings as the years funding by the Town of Southold. -

Venues of Popular Politics in London, 1790–C. 1845

2. ‘Bastilles of despotism’: radical resistance in the Coldbath Fields House of Correction, 1798–18301 In the early morning of 13 July 1802, the road from London to the town of Brentford was already buzzing with a carnival atmosphere. Thousands had assembled on foot while others rode in hackney coaches; riders on horseback and bands of musicians formed a cavalcade that snaked along the roadways.2 The 1802 elections for Middlesex had become a major spectacle in the metropolis during the month of July.3 Crowds assembled each day at the Piccadilly home of Sir Francis Burdett to accompany their hero to the hustings. Burdett, the independent Whig MP for Boroughbridge and vocal opponent of William Pitt, had been enticed to London to contest the Middlesex elections by his close radical supporters.4 The streetscape was a panorama of vivid deep blue: banners were draped across buildings, ribbons were tied and handkerchiefs waved in Burdett’s electoral colour by thousands of supporters. The occasional hint of light blue or splatter of orange in the crowd meant supporters of rival contestants, such as Tory MP William Mainwaring, had unwisely spilled into the procession.5 Three horsemen led the massive entourage, each bearing a large blue banner, with the words ‘No Bastille’ illuminated in golden letters. The words inflamed the otherwise festive throng; angry chants of ‘No magistrates’ and ‘No Bastille’ reverberated among the crowd. Newgate, however, was not the object of scorn, but rather a new prison, the Coldbath Fields House of Correction, and the Middlesex magistrates responsible for its management. -

CLEVELAND APL ADOPTIONS: October 2017

Cat adoptions: 326 Dog adoptions: 153 Gecko adoptions: 2 Guinea Pig adoptions: 4 Hamster adoptions: 1 Parakeet adoptions: 1 Rabbit adoptions: 11 Rat adoptions: 3 CLEVELAND APL ADOPTIONS: October 2017 Animal Name Species Primary Breed Age As Months Sex New Hometown Adoption Location Almond Joy Cat Domestic Shorthair 4 M CLEVELAND Cat Adoption, EAC Amy Cat Domestic Shorthair 13 F CLEVELAND Cat Adoption Andy Cat Domestic Shorthair 5 M CLEVELAND PetCo Angelica Cat Domestic Shorthair 3 F WILLOUGHBY Cat Adoption Autumn Cat Domestic Longhair 26 F STRONGSVILLE Cat Adoption, EAC Azelia Cat Domestic Shorthair 7 F CLEVELAND Cat Adoption Baby Cat Domestic Shorthair 134 F LAKEWOOD Cat Adoption Baby Girl Cat Siamese 76 F LAKEWOOD Cat Adoption, EAC Balbina Cat Domestic Medium Hair 4 F CLEVELAND Cat Adoption Barbara Ann Cat Domestic Shorthair 16 F BEREA Cat Adoption, EAC Basmati Cat Domestic Shorthair 61 F LAKEWOOD Cat Adoption Batman Cat Domestic Shorthair 4 M WESTLAKE Office Batty Cat Domestic Shorthair 4 F AVON Cat Adoption Beedrill 6 Cat Persian 74 F CLEVELAND Cat Playroom Bella Cat Domestic Shorthair 14 F CLEVELAND Cat Adoption Bella 16 Cat Domestic Shorthair 74 F CLEVELAND Cat Adoption Billy Cat Domestic Shorthair 3 M EUCLID Cat Adoption Billy Cat Domestic Shorthair 6 M NORTH RIDGEVILLE Cat Adoption Binx Cat Domestic Medium Hair 25 M CLEVELAND Cat Adoption Bonnie Cat Domestic Shorthair 4 F CLEVELAND Cat Adoption Bonnie Cat Domestic Shorthair 4 F CLEVELAND Cat Adoption, EAC Bootsie Cat Domestic Shorthair 51 F CLEVELAND Cat Adoption Boulder Cat Domestic