SRF Fund Management Handbook TABLE of CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Pollution Control State Revolving Fund 2017 Annual Report

MONTANA WATER POLLUTION CONTROL STATE REVOLVING FUND ANNUAL REPORT FOR STATE FISCAL YEAR 2017 (JULY 1, 2016 THROUGH JUNE 30, 2017) For EPA Region VIII November 2017 Prepared by Montana Department of Environmental Quality and Montana Department of Natural Resources & Conservation Cover photo: Yellowstone River near Billings, courtesy of Eric Regensburger, Montana DEQ THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK INTENTIONALLY SFY 2017 Annual Report for EPA-Wastewater i TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ........................................................................................... 3 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SFY16 ...................................................................................................... 3 III. GOALS OF THE WPCSRF ............................................................................................................. 5 IV. FINANCIAL REPORTS .................................................................................................................. 8 V. DETAILS OF WPCSRF ACTIVITY .................................................................................................... 8 VI. GRANT CONDITIONS AND CERTIFICATIONS ............................................................................ 10 VII. CURRENT STATUS AND PROPOSED IMPOVEMENTS .............................................................. 12 EXHIBITS Exhibit 1: Sources of WPCSRF Funds through SFY17 .................................................................... 14 Exhibit 2: WPCSRF Capitalized Grant Closed Loans for SFY17 ..................................................... -

Using the Clean Water State Revolving Fund

United States Environmental Protection Agency In 1987, Congress amended the Clean Water Act and New York Uses created the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) CWSRF to Fund to finance projects that improve water quality. The 51 Wetland Acquisition individual revolving funds combine federal and state money to provide low-interest loans for eligible The State of New York projects. Between $3 and $4 billion is loaned out has used its SRF as a each year to public and private organizations to low-cost way to fund improve water quality. As the loans are repaid, money land acquisition projects is available to be used again for new projects — a true that protect water revolving fund. Wetland preservation, restoration and quality. In 2000, the City creation projects are often eligible for funding under the CWSRF. of Rye, NY used a $3.1 million CWSRF short- Using the CWSRF for Nonpoint Who is eligible to apply for a CWSRF term, zero interest loan Source Pollution Control and Coastal loan? Because each state administers and sets its own to acquire and protect Management istorically, states have used CWSRF loans program priorities, loan eligibility varies from crucial land in the Long H to finance large municipal wastewater state to state. Typical applicants have been Island Sound Estuary. treatment facilities. However, in recent years, municipalities and other public This land acquisition, states have begun to redirect their funds to organizations.However, more than 15 states now accept loan applications from not-for- recommended in the help manage nonpoint source pollution (NPS). Unlike pollution that comes from direct profit organizations or private entities. -

Resolution Supporting Full Access by Investor-Owned Utilities to the Clean Water State Revolving Fund

Resolution Supporting Full Access by Investor-Owned Utilities to the Clean Water State Revolving Fund WHEREAS, With the passage of the 1987 amendments to the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (commonly referred to as the “Clean Water Act” or “CWA”), the U.S. Congress replaced the long-standing federal Construction Grants program with the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) program. The CWSRF program is available to fund a wide variety of water quality projects including all types of non-point source, watershed protection or restoration, and estuary management projects, as well as more traditional municipal wastewater treatment projects; and WHEREAS, Since its inception the CWSRF Program has provided $68 billion to water pollution control projects; and WHEREAS, The CWSRF is widely viewed as a successful partnership between federal and State governments in addressing important environmental problems; and WHEREAS, The Safe Drinking Water Act, as amended in 1996, established the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF) to make funds available to all drinking water systems, regardless of ownership, to finance infrastructure improvements. The program emphasizes providing funds to small and disadvantaged communities and to programs that encourage pollution prevention as a tool for ensuring safe drinking water; and WHEREAS, Under the Safe Drinking Water Act, investor-owned utilities are eligible for DWSRF loans, but under the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, investor owned utilities are not eligible for CWSRF loans; and WHEREAS, The 2004 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Clean Water Needs Survey estimated that nationwide capital investment needs for wastewater pollution control is $202.5 billion; and WHEREAS, The installation and refurbishment of wastewater treatment and collection systems, combined sewer overflow corrections, stormwater management and the extension of wastewater service to small communities, demands significant financial investment; and WHEREAS, On May 14, 2009, the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee passed S. -

Funding Resilient Infrastructure and Communities with the CWSRF

Funding Resilient Infrastructure and Communities with the Clean Water State Revolving Fund Variable weather events and natural disruptions, including floods, droughts, tornadoes, wildfires, and hurricanes, have adversely impacted communities across the United States in recent years. These events underscore the need for communities to build infrastructure and manage resources that can maintain performance when impacted by such disruptions. Today’s infrastructure challenges include not only needs for repair, upgrade, and replacement, but also ensuring infrastructure assets and communities are resilient to variable weather events. Financial Benefits of CWSRF Funding How the CWSRFs Work CWSRF assistance options deliver significant The Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) is a low- benefits and incentives to borrowers. CWSRF interest source of financing for a wide range of wastewater loans can provide the following benefits: infrastructure and water quality projects. The program is an effective partnership between EPA and the states as well as • Coverage of up to 100% of project costs; the territory of Puerto Rico. Each program has the flexibility to • Discounted loans below the market rate down to zero percent in some states; fund a variety of projects that address the most pressing water • Deferred payments of principal and/or quality needs. The state- and territory-administered programs interest; each operate like banks with federal and state contributions • Terms of up to 30 years and extended term used to capitalize the programs. These funds are used to make financing that reduces annual interest low-interest loans to local communities for water quality payments; projects and are then repaid to the CWSRFs over terms as long • Dedicated revenues for loan repayments as 30 years or the useful life of the project, whichever is less1. -

Using State Revolving Funds to Build Climate-Resilient Communities (PDF)

NRDC: Using State Revolving Funds to Build Climate-Resilient Communities (PDF) JUNE 2014 NRDC ISSUE PAPER IP:14-06-A Using State Revolving Funds to Build Climate-Resilient Communities AUTHORS: Ben Chou Becky Hammer Larry Levine ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to thank the TOSA Foundation and the Pisces Foundation for their generous support of this work. We also would like to thank Alisa Valderrama and Rob Moore at NRDC, Gary Belan at American Rivers, and Hal Sprague at the Center for Neighborhood Technology for their invaluable feedback. For more information please contact: Ben Chou Becky Hammer Larry Levine Policy Analyst, Water Program Project Attorney, Water Program Senior Attorney, Water Program 1314 Second Street 1152 15th Street, NW, Suite 300 40 West 20th Street Santa Monica, CA 90401 Washington, DC 20005 New York, NY 10011 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABOUT NRDC The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) is an international nonprofit environmental organization with more than 1.4 million members and online activists. Since 1970, our lawyers, scientists, and other environmental specialists have worked to protect the world’s natural resources, public health, and the environment. NRDC has offices in New York City, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Bozeman, MT, and Beijing and works with partners in Canada, India, Europe, and Latin America. Visit us at www.nrdc.org and follow us on Twitter @NRDC. NRDC’s policy publications aim to inform and influence solutions to the world’s most pressing environmental and public health issues. For additional policy content, visit our online policy portal at www.nrdc.org/policy. -

Florida's State Revolving Fund Programs

Florida’s State Revolving Fund Programs . 1 What is the State Revolving Fund? • Provide low interest loans for drinking water, wastewater, and storm water facilities • Revolves using loan repayments, investment earnings, and bond proceeds • Approximately $250 million available annually What Type of Programs are There? • The Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) Program funds infrastructure that protects public health, improves water quality, or promotes alternative water supply projects. • The Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF) Program funds infrastructure projects that are intended to facilitate compliance with the requirements in the Safe Drinking Water Act. How do the Programs Work? CWSRF Eligible Sponsors • Local governments are eligible for loans to control wastewater, stormwater and nonpoint source pollution • Non-governmental parties are eligible for loans to control stormwater pollution related to agricultural operations. DWSRF Eligible Sponsors • All cities, counties, and authorities • Private drinking water systems What are the Loan Terms? • Generally, these loans have 20 year terms, but terms up to 30 years are possible for financially disadvantage communities. • Semi-annual repayments begin no more than one year after construction is complete. • Financing rates are fixed upon loan execution and average less than half of the market rate. State Revolving Fund Loan Interest Rates • Loan interest rate is a percentage of the base financing rate (Thompson 20- bond GO index) • Interest rates range from 0 percent to the -

FINAL 2021 INTENDED USE PLAN for the DRINKING WATER STATE REVOLVING FUND April 13, 2021

Charles D. Baker Kathleen A. Theoharides Governor Secretary Karyn E. Polito Martin Suuberg Lieutenant Governor Commissioner FINAL 2021 INTENDED USE PLAN For the DRINKING WATER STATE REVOLVING FUND April 13, 2021 This information is available in alternate format. Contact Michelle Waters-Ekanem, Director of Diversity/Civil Rights at 617-292-5751. TTY# MassRelay Service 1-800-439-2370 MassDEP Website: www.mass.gov/dep Printed on Recycled Paper Final 2021 Intended Use Plan for the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) is pleased to present the Final Calendar Year 2021 Intended Use Plan (IUP), which lists the projects, borrowers, and amounts that will be offered financing through the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF) loan program. The DWSRF is a joint federal-state financing program that provides subsidized loans to protect public health by improving water supply infrastructure systems and protect drinking water in the Commonwealth. Massachusetts is offering approximately $195 million to finance drinking water projects across the Commonwealth. As noted in Table 1, approximately $166 million is being offered to finance 21 new construction projects, an additional $22.7 million will be allocated to finance 6 previously approved multi-year projects, and approximately $1.3 million is allocated towards the 6 planning projects. An additional $5 million has been allocated to the emergency set-aside account. Two (2) proposals, totaling $259,788, as noted in Table 2, have been selected to receive financial assistance for their Asset Management Planning (AMP) projects. Communities will receive 60% of the project cost, up to $150,000, as a grant from the Massachusetts Clean Water Trust (Trust), totaling $155,738. -

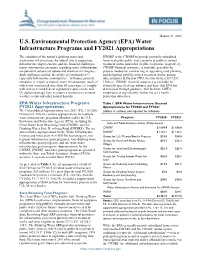

(EPA) Water Infrastructure Programs and FY2021 Appropriations

January 11, 2021 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Water Infrastructure Programs and FY2021 Appropriations The condition of the nation’s drinking water and DWSRF or the CWSRF to provide primarily subsidized wastewater infrastructure, the federal role in supporting loans to eligible public water systems or publicly owned infrastructure improvements, and the financial challenges treatment works (and other eligible recipients), respectively. many communities encounter regarding water infrastructure CWSRF financial assistance is available generally for are perennial subjects of debate and attention in Congress. projects needed for constructing or upgrading (and planning Such challenges include the ability of communities— and designing) publicly owned treatment works, among especially low-income communities—to finance projects other purposes defined in CWA Section 603(c) (33 U.S.C. needed to (1) repair or replace water infrastructure, much of 1383(c)). DWSRF financial assistance is available for which was constructed more than 50 years ago; (2) comply statutorily specified expenditures and those that EPA has with new or revised federal regulatory requirements; and determined, through guidance, will facilitate SDWA (3) address damage from or improve resilience to extreme compliance or significantly further the act’s health weather events and other natural hazards. protection objectives. EPA Water Infrastructure Programs Table 1. EPA Water Infrastructure: Enacted FY2021 Appropriations Appropriations for FY2020 and FY2021 The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 (P.L. 116-260), (dollars in millions, not adjusted for inflation) Division G, Title II, contains appropriations for multiple water infrastructure programs administered by the U.S. Program FY2020 FY2021 Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), including the State and Tribal Assistance Grants (STAG) Account Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) and the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF). -

2020 Kansas Water Pollution Control Revolving Fund Annual Report

Kansas Water Pollution Control Revolving Fund Annual Report for Fiscal Year 2020 September 30, 2020 Prepared by: Kansas Department of Health and Environment Division of Environment Bureau of Water Curtis State Office Building 1000 Jackson St Topeka KS, 66612 Table of Contents I. Introduction ...................................................................................................1 II. Program Description .....................................................................................1 III. Goals and Objectives ....................................................................................2 IV. Loan Fund Activity .......................................................................................6 V. Fund Financial Status ....................................................................................9 VI. Compliance with Assurances and Grant Conditions ...................................12 Figures Figure 1 KWPCRF Loan Fund Amounts ....................................................................7 Figure 2 KWPCRF # of Loan Agreements .................................................................7 Figure 3 FY 2020 New Sources ..................................................................................9 Figure 4 Cumulative Sources .....................................................................................10 Tables Table 1 State Match and Associated Grants ...................................................................1 Table 2 Loan Descriptions .........................................................................................8 -

The Drinking Water State Revolving Fund Financing America’S Drinking Water

United States Office of Water EPA-816-R-00-023 Environmental Protection (4606) November 2000 Agency The Drinking Water State Revolving Fund Financing America’s Drinking Water DWSRF —A Report of Progress Financing America’s The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Drink- ing Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF) program is a significant tool available to states to fund high-priority infrastructure projects and state and local activities needed to ensure the provision of safe and affordable drinking water. The DWSRF program is well on its way toward meeting the goal of helping to ensure that permanent institutions exist in each state to provide financial support for drinking water needs for many years to come. Through June 30, 2000: : EPA has provided more than $2.7 billion in grants to all 50 states and Puerto Rico to capitalize revolving loan funds for infrastructure projects and to fund state and local activities. : States have made close to 1,200 “As a result of this program, low-interest loans totaling more we now provide safer than $2.3 billion for needed drinking water to over 2,000 drinking water infrastructure projects to meet public health and people. We would not have compliance objectives. gotten this far without the : Seventy-five percent of all loans Drinking Water State have gone to small water systems. Revolving Fund.” : States have reserved $445 million for activities that support their —Stan Bullard drinking water programs, enhance Vice President of Camp Verde the management ability of water Arizona Water System which received a loan to address high systems, and protect sources of arsenic levels in its drinking drinking water. -

OWRB Requests Comments on the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) Proposed Amendment #1 to the SFY 2004 Intended Use Plan

April 12, 2004 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION, PLEASE CONTACT: Julie Cunningham Financial Assistance Division Oklahoma Water Resources Board (405) 530-8800 OWRB Requests Comments on the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) Proposed Amendment #1 to the SFY 2004 Intended Use Plan The 1987 amendments to the Federal Clean Water Act provided for states to establish an ongoing Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) loan program. This program enables eligible entities to receive low-interest financing for eligible wastewater construction projects, including treatment works and urban storm water run off projects, and nonpoint source pollution control activities. Repayments of these loans, along with federal and state funds and investment income, provide financing for future water pollution control loans. The OWRB administers the program and is responsible for preparing the annual Intended Use Plan (IUP), a document which establishes program goals, identifies sources and uses of funds, and provides a ranked listing of projects proposed by communities requesting to receive loan funds. Since the June 20, 2003, public meeting to discuss the FY 2004 CWSRF IUP, the City of Henryetta, Oklahoma, has submitted a letter requesting to be considered for a refinancing loan through the CWSRF during FY 2004, to provide refinancing for a previous USDA Rural Development refinancing loan, closed on March 28, 1997. In addition, projected target dates and loan amounts of several proposed loans currently on the list have been updated. In accordance with program regulations, the FY 2004 CWSRF IUP is being amended following required public notice. The Oklahoma Water Resources Board requests comments on this proposed amendment to the CWSRF FY 2004 Intended Use Plan. -

Drinking Water State Revolving Fund Annual Intended Use Plan SFY 2021

Drinking Water State Revolving Fund Annual Intended Use Plan SFY 2021 State of Connecticut Department of Public Health Drinking Water Section Drinking Water State Revolving Fund Intended Use Plan SFY 2021 This page is intentionally blank 10/26/2020 Drinking Water State Revolving Fund Intended Use Plan SFY 2021 Table of Contents List of Acronyms Used in this Document I. Introduction A. State of Connecticut’s Drinking Water State Revolving Fund B. What’s New for SFY 2021 II. Structure of the DWSRF A. Eligibility of Projects for Planning, Design, and Construction B. Set-Asides III. DWSRF Goals A. Short-Term Goals B. Long-Term Goals IV. Criteria and Method for Distribution of Project Funds A. Priority Ranking System B. Capacity Assessments C. Projects to be Funded D. Small System Funding E. Emergency Power Generator Program F. Small Loan Program for Non-Construction Projects G. Federal Subsidy Funds and Disadvantaged Community Assistance Program H. State Subsidy Funds – Public Water System Improvement Program I. Readiness to Proceed J. Project Bypass Procedures K. Other DWSRF Provisions L. Connecticut Plan of Conservation and Development V. DWSRF Policies and Requirements A. Letter of Authorization to Award for Eligible Projects B. Project Application Carryovers and Rollovers C. Multi-Year Projects D. Tie-Breaking Procedures E. Pre-Review Policy (Construction Only) F. Reimbursements G. Refinancing Existing Loans H. Withdrawal of Project from Funding Consideration I. Use of Excess Project Funds J. Replacement of Lead Service Lines when Replacing Water Main VI. Financial Management A. Rationale for Determining Amounts of Capitalization Grant Intended for Projects and Set-Aside Funds B.