Board of Homeopathic Medical Examiners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMERICAN OSTEOPATHIC BOARD of PREVENTIVE MEDICINE and Evaluation That Is Designed and Administered by Specialists in the Specific Area of Medicine

AOCOPM Midyear Educational Meeting Marc 8-11, 2018, San Antonio AMERICAN OSTEOPATHIC BOARD BOARD CERTIFICATION OF PREVENTIVE • Board certification demonstrates to the public that a physician has met or exceeded the training MEDICINE (AOBPM) requirements, knowledge and expertise in a particular specialty and/or subspecialty of medical practice. DANIEL K. BERRY,DO, PHD • Certification involves a rigorous process of testing CHAIR, AMERICAN OSTEOPATHIC BOARD OF PREVENTIVE MEDICINE and evaluation that is designed and administered by specialists in the specific area of medicine. BENEFITS OF BOARD CERTIFICATION • A physician may practice Medicine in the United States with just a medical license • However, a medical license alone does not demonstrate that a physician has skills and expertise in a specialty or subspecialty of medicine. • Board Certification demonstrates that a physician has accomplished the specialty training, and has verified their knowledge in that specialty through testing and evaluation. • Board Certification demonstrates skills and expertise in a specialty; a mastery of the basic knowledge and skills that define that specialty BENEFITS OF BOARD CERTIFICATION REIMBURSEMENT FOR BOARD CERTIFIED PHYSICIANS • Board certification is expensive and time-consuming. And it’s almost as much a necessity for practicing medicine today as a medical degree. • Physician Quality Reporting Initiative, Medicare’s pay-for-performance • Certification is a prerequisite for privileges at most hospitals • Physicians can qualify for additional payments if they submit data measures through a maintenance-of-board-certification (MOC) program. National Committee for Quality • Certification is a prerequisite for credentialing by most insurers Assurance (NCQA) is at least partially predicated on board certification. NCQA recognition • Few practices will hire physicians who aren’t board-certified qualifies physicians for many national and regional pay-for-performance efforts. -

US States and Territories Modifying

U.S. States and Territories Modifying Licensure Requirements for Physicians in Response to COVID-19 (Out-of-state physicians in-person practice; license renewals) Last Updated: September 15, 2021 States with Waivers: 22 + DC + GU + USVI States with Waivers, not allowing new applications: 0 States without Waivers (or closed waivers): 28 States allowing OOS physicians long-term or permanent privileges: 4 + CNMI + PR On January 28, 2021, HHS announced the fifth amendment to the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness (PREP) Act, authorizing any healthcare provider who is licensed or certified in a state to prescribe, dispense, or administer COVID-19 vaccines in any other state or U.S. territory. The amendment also authorizes any physician, registered nurse, or practical nurse whose license or certification expired within the past five years to partake in the immunization effort, but first must complete a CDC Vaccine Training and an on-site observation period by a currently practicing healthcare professional. State Note Citation • The Alabama Board of Medical Examiners and the Medical Licensure Commission have adopted emergency administrative rules and procedures allowing for the emergency ALBME Press Release licensing of qualified medical personnel. These measures will allow physicians and physician assistants who possess full and unrestricted medical licenses from appropriate medical licensing agencies to apply for and receive temporary emergency licenses to Board of Med Guidance practice in Alabama for the duration of the declared COVID-19 health emergency. • Re: renewals - The Board and Commission recognize the difficulty licensees may have meeting the annual continuing medical education requirement in 2020 due to the public Temporary Emergency health emergency. -

International Medical School Graduate Application

STATE AND CONSUMER SERVICES AGENCY- Department of Consumer Affairs EDMUND G. BROWN JR., Governor MEDICAL BOARD OF CALIFORNIA Licensing Program GENERAL INFORMATION For individuals applying for a Physician’s and Surgeon’s Medical License or a Postgraduate Training Authorization Letter (PTAL) Please carefully read the information on this General Information and the Application Instructions prior to beginning the process of completing the application forms and requesting all applicable supporting materials. These information sheets are designed to answer questions relative to the application process. As an applicant, you are personally responsible for all information disclosed on your application, Forms L1A-L1E, including any responses that may have been completed on your behalf by others. An application may be denied based upon falsification or misrepresentation of any item or response on the application or any attachment. Any alterations to any application and/or supporting application forms may result in the denial of your application. The Medical Board considers violations of an ethical nature to be a serious breach of professional conduct. REQUIREMENTS FOR PRINTING APPLICATION FORMS: The application forms and instructions may be downloaded to your personal computer and printed with your local printer. It is recommended that you use a high speed connection to download all forms; however, lower speed connections can download the forms. The forms require Adobe Acrobat plug-in version 5.0 or higher. It is recommended that the forms be printed using a laser jet printer. All application responses must be in the form of a A @ or A@. No shaded responses will be accepted. RESOURCES AND REFERENCES: The Medical Board of California official Web site address is: www.mbc.ca.gov. -

US International Medical Graduate Limited MA License For

All documents must be sent directly to your BMC training program’s office, NOT to the Mass Board of Registration in Medicine. Anything sent to the Board will need to be duplicated and sent to BMC. International Medical Graduate Checklist 1. Name Printed on Top of each page 2. Every Question is answered (n/a is unacceptable) 3. Signed & Dated Page 6 of application 4. Signed & Dated Authorization for Release 5. Provided explanation if you attended medical school for more than 6 years 6. Attached an up‐to‐date CV in Month/Year format a. All 30 day+ gaps will require a separate letter of explanation 7. Completed Medical Education Verification Form, include Medical School transcripts 8. Notarized Medical School Diploma 9. Notarized ECFMG Certificate + Request Online Status Report 10. Request Exam Score Transcripts (USMLE, COMPLEX, LMCC) 11. Only If Applicable: a. Provide English Translations of any documents in the home country language. i. Translations must be from a US Company or from the Medical School with Medical School Seal on each page. b. Social Security Affidavit; Submit if you do not currently have a US Social Security Number c. Supplemental Forms; submit if you answered YES to any questions from 16 through 35 d. Letter from the director of your most recent training program if you did not complete the program e. Evaluation Form; Completed by your most recent Program Director f. License Verification Form; submit one form for each state you have held a Full Medical License in g. Medical Education Verification Form B; applicable only to those who will graduate Medical School after submission of this application h. -

Uniform Application Instructions And

State of West Virginia West Virginia Board of Medicine 101 Dee Drive, Suite 103 Charleston, WV 25311 Telephone (304) 558-2921 Fax (304) 558-2084 Dear Applicant: We thank you for your interest in obtaining a medical license in the State of West Virginia. It is our goal to see that you receive your license in the shortest time possible with as little inconvenience as possible. If you follow the steps outlined below, you will assist in expediting the processing of your application: 1. Confirm Eligibility. Please determine if you meet the eligibility requirements as listed in these instructions and in the West Virginia Medical Practice Act and Rules prior to making application. As quoted from §30-3-10(i): The Board may not issue a license to a person not previously licensed in West Virginia whose license has been revoked or suspended in another state until reinstatement of his or her license in that state. 2. Complete the application as soon as possible. The application process will not begin until the Board electronically receives the Uniform Application with fee; and either through the mail or overnight delivery service to the Board office the Photo Affidavit and Addendum 1. Be aware that since licensure approval occurs at the bi-monthly Board meetings, completion of the licensure process generally occurs within three to six months from the date your application is received in this office. 3. Be complete. We receive information from more than one source. As a result, it is crucial for you to provide complete information. Omissions or discrepancies will delay the process. -

BRD RPT 20-3 REPORT of the BOARD of DIRECTORS Subject: Report on Resolution 19-1: Licensing Exam Research (Minnesota Board of Me

BRD RPT 20-3 REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Subject: Report on Resolution 19-1: Licensing Exam Research (Minnesota Board of Medical Practice) Referred to: Reference Committee ________________________________________________________________________ At the April 2019 Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) House of Delegates (HOD) meeting, the Minnesota Board of Medical Practice submitted Resolution 19-1: Correlation between licensee USMLE or COMLEX passage attempt rate and reports of state medical board discipline: Resolved, the FSMB will establish a task force to study existing licensing regulations on USMLE and COMLEX passage rate attempts, time duration to USMLE and COMLEX passage, and subsequent medical board discipline, medical malpractice claims, and other measures of clinical aptitude; and Resolved, that the FSMB task force will evaluate whether mandatory limitations on USMLE and COMLEX passage attempts and/or limitations to the time duration to USMLE and COMLEX step passage correlate with a decrease in future medical board disciplinary action, medical malpractice claims, and other measures of clinical aptitude; and Resolved, that the FSMB task force will develop recommendations regarding mandatory USMLE and COMLEX passage attempt and time limitations for licensure by medical boards in the United States and its territories. At the Reference Committee meeting, the FSMB Board of Directors testified that research already exists to address some of the issues in the resolution, and that several streams of work were already underway -

(Md/Do) New License Application

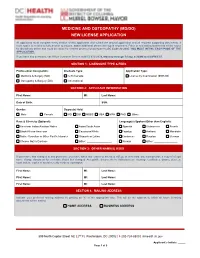

MEDICINE AND OSTEOPATHY (MD/DO) NEW LICENSE APPLICATION All applicants must complete every section of this application and submit the original application and all required supporting documents. If more space is needed to fully answer questions, attach additional sheets with typed responses. False or misleading statements will be cause for disciplinary action and could be cause for criminal prosecution pursuant to DC Code 22-2405. YOU MUST INITIAL EACH PAGE OF THE APPLICATION. If you have any questions, call HRLA Customer Service at (877) 672-2174, Monday through Friday, 8:30AM to 4:00PM EST. SECTION 1: LICENSURE TYPE & FEES Professional Designation: Graduate Type: Application Type: Medicine & Surgery (MD) U.S./Canada License by Examination ($805.00) Osteopathy & Surgery (DO) International SECTION 2: APPLICANT INFORMATION First Name: MI: Last Name: Date of Birth: SSN: Gender: Degree(s) Held: Male Female MD DO MBBS MBA MPH PHD Other: Race & Ethnicity (Optional): Language(s) Spoken (Other than English): American Indian/Alaskan Native Asian/South Asian Spanish Vietnamese French Black/African American Caucasian/White Tagalog Amharic Mandarin Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander Hispanic or Latino Cantonese Russian German Choose Not to Disclose Other: _________________ Korean Other: ________________ SECTION 3: OTHER NAME(S) USED If your name has changed at any point since you have taken any exams or attended college or university, you must provide a copy of a legal name change document for each time that it has changed. Acceptable documents for individuals are marriage certificates, divorce decrees, court orders, copies of social security cards or a passport. First Name: MI: Last Name: First Name: MI: Last Name: First Name: MI: Last Name: SECTION 4: MAILING ADDRESS Indicate your preferred mailing address by placing an “X” in the appropriate box. -

DISTRICT of COLUMBIA MUNICIPAL REGULATIONS for MEDICINE

Title 17 District of Columbia Municipal Regulations DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA MUNICIPAL REGULATIONS for MEDICINE October 2007 Title 17 District of Columbia Municipal Regulations CHAPTER 46 MEDICINE Secs. 4600 General Provisions 4601 Term of License 4602 Educational and Training Requirements 4603 Applicants Educated in Foreign Countries 4604 Applicants Educated in the Fifth Pathway Program 4605 National Examination 4606 Continuing Education Requirements for Nonpracticing Physicians 4607 Approved Continuing Education Programs and Activities 4608 Foreign Educated Applicants of Conceded Eminence 4609 Physician Profile 4610 License by Waiver of National Examination 4611 Pre-Licensure Practice by Students and Postgraduate Physicians 4612 Standards of Conduct 4613 Credentialing 4614 Standards for the Use of Controlled Substances for the Treatment of Pain 4615 Continuing Education Requirements for Practicing Physicians 4616 Approved Continuing Education Programs and Activities 4699 Definitions 4600 GENERAL PROVISIONS 4600.1 This chapter shall apply to applicants for and holders of a license to practice medicine. 4600.2 Chapters 40 (Health Occupations: General Rules), 41 (Health Occupations: Administrative Procedures) of this title shall supplement this chapter. 4600.3 The Board shall only accept applications for licensure by one of the following means notwithstanding anything in Chapter 40 to the contrary: (a) National examination; (b) Waiver of national examination (c) Reactivation of an inactive license; (d) Reinstatement of an expired, suspended, or revoked license; or (e) Eminence pursuant to D.C. Official Code § 3-1205.09a (2001). 4600.4 An applicant shall establish to the Board’s satisfaction that the applicant possesses appropriate skills, knowledge, judgment, and character to practice medicine. 4600.5 An applicant shall demonstrate to the satisfaction of the Board that the applicant is proficient in understanding and communicating medical concepts and information in English. -

Instructions for Completing the License Application for a New Jersey Medical License

Instructions for completing the license application for a New Jersey Medical License Read the application and instructions before completing the application. Each section of the application is explained in these instructions -follow them carefully. Completing the enclosed application and mailing it to the Board office does not constitute the completion of your application. You must request verifications and certifications from schools, employers, etc.(third parties) using forms enclosed in this packet and follow-up with the third parties to ensure materials are sent directly to the Board office. Do not substitute a different form/document for the one requested or those provided with the application. Your application cannot be reviewed and approved until all documentation regarding your education, post- graduate training and professional experience are received. Request verification from all third parties immediately. Get them expedited, if possible. The application must be submitted with a certified check or money order in the amount of $325.00 (nonrefundable) and three photographs, which must be signed and dated. An endorsement fee and registration fee will be requested just prior to your license being issued. Your application reviewer will inform you regarding how much is owed when it is due. Type or print neatly. All questions must be answered. For “Yes” or “No” questions, circle the correct answer. If you determine a question does not apply to you, please indicate that fact by writing “N/A” as your response. When space provided is insufficient, attach additional sheets of paper. Print your first name, middle initial and last name on each page of the application and on each attachment. -

Medicine Board Briefs September 2018

BOARD BRIEFS #86 SEPTEMBER 2018 1. New Board of Medicine Members 2. Final Regulations for Opioid and Buprenorphine Prescribing 3. FAQ’s on Opioids 4. Comments from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD 5. On Narx Scores from the Prescription Monitoring Program 6. Cannabidiol oil and THC-A oil Registration and Certifications 7. Helping Your Patients Understand Costs 8. Medicaid Expansion will soon be here! 9. Mixing, Diluting or Reconstituting Audits 10. MDR Audit Tool 11. Nurse Practitioner Regulations for Autonomous Practice 12. Licensure by Endorsement 13. Survey on Telehealth from Mara Servaites of the Virginia Telehealth Network 14. Message to Midwives from Kim Pekin, LM & Chair of the Advisory Board on Midwifery 15. Electronic Death Registration System (EDRS) 16. Physician Burnout Resources VIRGINIA BOARD OF MEDICINE BOARD BRIEFS #86 BOARD BRIEFS #86 SEPTEMBER 2018 17. DEA Policy on Mobile Devices for Electronic Prescriptions 18. New Laws 19. Board of Medicine Regulations Underway 20. Recent Meeting Minutes 21. Upcoming Meetings 22. Board Members 2017-2018 23. Advisory Board Members 24. Board Decisions 2 | Page VIRGINIA BOARD OF MEDICINE BOARD BRIEFS #86 New Board of Medicine Members The Board thanks all departing members and welcomes all new members. James Arnold, DPM-Podiatrist, succeeding Randy Clements, DPM 1st Term Expires June 2022 Podiatrist – Cross Junction Manjit Dhillon, MD-Orthopedist, succeeding David Taminger, MD Unexpired Term Expires June 2020 District: 4 – Chester L. Blanton Marchese-Citizen Member, succeeding James -

Rules and Regulations for Limited Medical Registration

RULES AND REGULATIONS FOR LIMITED MEDICAL REGISTRATION [R5-37-REG] STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH December 1982 AS AMENDED: January 1986 October 2007 January 2002 (re-filing in January 2012 (re-filing in accordance with the provisions accordance with the provisions of section 42-35-4.1 of the of section 42-35-4.1 of the Rhode Island General Laws, as Rhode Island General Laws, as amended) amended) October 2004 September 2012 January 2007 (re-filing in October 2015 (Repeal) accordance with the provisions of section 42-35-4.1 of the Rhode Island General Laws, as amended) REGULATIONS ARE TO BE REPEALED IN THEIR ENTIRETY INTRODUCTION These amended Rules and Regulations For Limited Medical Registration [R-5-37REG] are promulgated pursuant to the authority conferred under section 23-17-10 of the General Laws of Rhode Island, as amended, and are established for the purpose of adopting prevailing standards for limited medical registration. In accordance with the provisions of section 42-35-3(c) of the General Laws of Rhode Island, as amended, consideration was given to: (1) alternative approaches to the amendments; and (2) duplication or overlap with other state regulations. Based on available information, no known alternative approach, duplication or overlap was identified. Upon promulgation, these amended regulations shall supersede all previous Rules and Regulations for Limited Medical Registration promulgated by the Department of Health and filed with the Secretary of State. i PART I Definitions Section 1.0 Definitions Wherever used in these rules and regulations the following terms shall be construed to mean: 1.1 "Act" refers to Chapter 5-37 of the General Laws of Rhode Island, as amended, entitled, “Board of Medical Licensure and Discipline." 1.2 “Attending physician” means a physician who has an active, full medical license. -

State and Territory COVID Telehealth Waivers

State and Territory COVID Telehealth Waivers Existing Prior in Person Originating Site Reimbursement Reimbursement Telehealth Emergency Licensure Process for Out of State Contact Requirement Audio-Only Supervision Reimbursement Parity Private Out of State Statute Licensure Waiver In Effect Physicians Required Waived Allowed? Trainees and Post-Doc Allowed Parity Medicaid Insurers Providers Other Considerations After November 17, 2020, all temporary emergency licensees that wish to continue The Board and Commission have established Per guidance from the practicing in Alabama temporary emergency licensure processes to Medicaid office, it is unclear Alabama No Yes should apply now for authorize physicians to provide health care to No Yes Yes whether interns and postdocs Yes Varies by insurer Yes permanent licensure Alabamians suffering from and affected by are able to perform telehealth through the Board Covid. services. (typically 2-3 months) or the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (within 30 days). For as long as the Secretary’s designation of a PHE remains in effect, DEA-registered practitioners may issue prescriptions for controlled substances to patients for whom they have not conducted an in-person medical evaluation, provided all of the Out-of-state licensed phsycians must obtain an following conditions are met: Alaska Stat. § Yes, active despite the emergency courtesy license to provide care to As trainees are not licensed, (1) The prescription is issued for a No (in existing Yes (existing law Alaska 21.42.422; § Yes conclusion of the State of patients in Alaska within the scope of their Yes they are not eligible to Yes Yes Yes legitimate medical purpose by a statute) allows) 47.05.270 Emergency.