Jkpo;J; Njrpa Mtzr; Rtbfs;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia List of Commanders of the LTTE

4/29/2016 List of commanders of the LTTE Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia List of commanders of the LTTE From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The following is a list of commanders of theLiberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), also known as the Tamil Tigers, a separatist militant Tamil nationalist organisation, which operated in northern and eastern Sri Lanka from late 1970s to May 2009, until it was defeated by the Sri Lankan Military.[1][2] Date & Place Date & Place Nom de Guerre Real Name Position(s) Notes of Birth of Death Thambi (used only by Velupillai 26 November 1954 19 May Leader of the LTTE Prabhakaran was the supreme closest associates) and Prabhakaran † Velvettithurai 2009(aged 54)[3][4][5] leader of LTTE, which waged a Anna (elder brother) Vellamullivaikkal 25year violent secessionist campaign in Sri Lanka. His death in Nanthikadal lagoon,Vellamullivaikkal,Mullaitivu, brought an immediate end to the Sri Lankan Civil War. Pottu Amman alias Shanmugalingam 1962 18 May 2009 Leader of Tiger Pottu Amman was the secondin Papa Oscar alias Sivashankar † Nayanmarkaddu[6] (aged 47) Organization Security command of LTTE. His death was Sobhigemoorthyalias Kailan Vellamullivaikkal Intelligence Service initially disputed because the dead (TOSIS) and Black body was not found. But in Tigers October 2010,TADA court judge K. Dakshinamurthy dropped charges against Amman, on the Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, accepting the CBI's report on his demise.[7][8] Selvarasa Shanmugam 6 April 1955 Leader of LTTE since As the chief arms procurer since Pathmanathan (POW) Kumaran Kankesanthurai the death of the origin of the organisation, alias Kumaran Tharmalingam Prabhakaran. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications For

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Pattukkottai Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 16/11/2020 Madhavan Selvarani (M) A21, New Housing Unit, Ponnavarayankottai, , 2 16/11/2020 Alangaram Ramanujam (F) 38-1/38, Taste Bakery Colony Rajapalayam Street, Pattukottai, , 3 16/11/2020 Indrani Alangaram (H) 38-1/38, Taste Bakery Colony Rajapalayam Street, Pattukottai, , 4 16/11/2020 RAMYABHARATHI SRI RAJAMOHAN (F) 27D, THACHA STREET, R M PATTUKKOTTAI, , 5 16/11/2020 Aishwarya K Kamaraj (F) 7, Kondapa Nayakan Palayam, Pattukkottai, , 6 16/11/2020 RAGAVENDHIRAN V VEERA K (F) 33, BHARATHI NAGAR, PATTUKKOTTAI, , 7 16/11/2020 rajeshwari Ragulgandhi Ragulgandhi ragulgandhi 246/3A, Adhithiravidar (H) pallikondan, pallikondan, , 8 16/11/2020 rajeshwari Ragul gandhi Ragul ganthi ragul gandhi 246/3A, adhithiravidar street, (H) pallikondan, , 9 16/11/2020 MOHAMED JAMEEL RAJIK AHAMED (F) 38B, AMBETHKAR NAGAR, RAJIK AHAMED ADIRAMPATTINAM, , 10 16/11/2020 MUSTHAQ AHAMED NIJAMUDEEN (F) 3, AMBETHKAR NAGAR, ADIRAMPATTINAM, , £ In case of Union territories having no Legislative Assembly and the State of Jammu and Kashmir Date of exhibition at @ For this revision for this designated location designated location under Date of exhibition at Electoral * Place, time and date of hearings as fixed by electoral registration officer rule 15(b) Registration Officer¶s Office under $ Running serial number is to be maintained for each revision for each designated rule 16(b) location # Give relationship as F-Father, M=Mother, and H=Husband within brackets i.e. -

A Study of Violent Tamil Insurrection in Sri Lanka, 1972-1987

SECESSIONIST GUERRILLAS: A STUDY OF VIOLENT TAMIL INSURRECTION IN SRI LANKA, 1972-1987 by SANTHANAM RAVINDRAN B.A., University Of Peradeniya, 1981 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Political Science We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 1988 @ Santhanam Ravindran, 1988 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Political Science The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date February 29, 1988 DE-6G/81) ABSTRACT In Sri Lanka, the Tamils' demand for a federal state has turned within a quarter of a century into a demand for the independent state of Eelam. Forces of secession set in motion by emerging Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinism and the resultant Tamil nationalism gathered momentum during the 1970s and 1980s which threatened the political integration of the island. Today Indian intervention has temporarily arrested the process of disintegration. But post-October 1987 developments illustrate that the secessionist war is far from over and secession still remains a real possibility. -

Professional-Address.Pdf

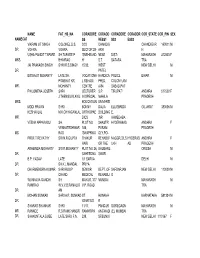

NAME FAT_HS_NA CORADDRE CORADD CORADDRE CORADDR COR_STATE COR_PIN SEX NAMECAT SS RESS1 SS2 ESS3 VIKRAM JIT SINGH COLONEL D.S. 3/33 CHANDIG CHANDIGAR 160011 M DR. VOHRA VOHRA SECTOR 28- ARH H USHA PANDIT TAPARE SH.TAPARE P 'SNEHBAND NEAR DIST- MAHARASH 412803 F MRS. BHIMRAO H' S.T. SATARA TRA JAI PRAKASH SINGH SHRI R.S.SINGH 15/32, WEST NEW DELHI M DR. PATEL BISWAJIT MOHANTY LATE SH. VOCATIONA HANDICA POLICE BIHAR M PRABHAT KR. L REHABI. PPED, COLONY,ANI MR. MOHANTY CENTRE A/84 SABAD,PAT PHILOMENA JOSEPH SHRI LECTURER S.P. TIRUPATI ANDHRA 517502 F J.THENGUVILAYIL IN SPECIAL MAHILA PRADESH MRS. EDUCATION UNIVERSI MODI PRAVIN SHRI BONNY DALIA ELLISBRIDG GUJARAT 380006 M KESHAVLAL M.K.CHHAGANLAL ORTHOPAE BUILDING E, MR. DICS ,NR AHMEDABA VEENA APPARASU SH. PLOT NO SHASTRI HYDERABAD ANDHRA F VENKATESHWAR 188, PURAM PRADESH MS. RAO 'SWAPRIKA' CLY,PO- PROF.T REVATHY SRI N.R.GUPTA THAKUR REHABI.F NAGGR,DILS HYDERAB ANDHRA F HARI OR THE UKH AD PRADESH ARABINDA MOHANTY SRI R.MOHANTY PLOT NO 24, BHUBANE ORISSA M DR. SAHEEDNA SWAR B.P. YADAV LATE 1/1 SARVA DELHI M DR. SH.K.L.MANDAL PRIYA DHARMENDRA KUMAR SHRI ROOP SENIOR DEPT. OF SAFDARJAN NEW DELHI 110029 M DR. CHAND MEDICAL REHABILI G WUNNAVA GANDHI SH MAYUR, 377 MUMBAI MAHARASH M RAMRAO W.V.V.B.RAMALIG V.P. ROAD TRA DR. AM MOHAN SUNKAD SHRI A.R. SUNKAD ST. HONAVA KARNATAKA 581334 M DR. IGNATIUS R SHARAS SHANKAR SHRI 11/17, PANDUR GOREGAON MAHARASH M MR. RANADE R.S.RAMCHANDR RAMKRIPA ANGWADI (E), MUMBAI TRA DR. -

"Early Militancy" from " Tigers of Lanka"

www.tamilarangam.net "Early militancy" from " Tigers of Lanka" [Part 1] [Part 2] [Part 3] [Part 4] [Part 5] This is the 1st part of "Early militancy" from " Tigers of Lanka", written by M.R.Nayaran Swamy. This chapter has the history of Sivakumaran and others. Early Militancy ( Part 1 ) It is VIRTUALLY impossible to set a date for the genesis of Tamil militancy in Sri Lanka. Tamils began weaving dreams of an independent homeland much more militancy erupted, albeit in an embryonic form, in the late 1960s and early 1970s. After 1956 riots, a group of tamils organised and opened fire at the Sri Lankan army in Batticaloa. Two Sinhalese were killed when 11 Tamils, having between them seven rifles, fired at a convoy of Sinhalese civi- lians and govt officials one night at a village near Kalmunai. There was another attcak on army soldiers in Jaffna after Colombo stifled the Federal Party "satyagraha" in 1961, but no one was killed. The failure of the 1961 "satyagraha" set several of its leading lights thinking. Mahatma Gandhi, they argued, succeeded in India with his concept of non-violence and non-cooperation because he was leading a majority against a minority, however powerful; whereas in Sri Lanka, the Tamils were a minority seeking rights from a majority. And the majority was not willing to give concessions. Some of 20 men associated with the Federal Party thought Gandhism had no place in sucha scenario. They decided after the prolonged deliberations to form an underground group to fight for a separate state. Most of them were civil servants and had been influenced by Leon Uris Exodus. -

Geneva's Human Rights Chameleons

Geneva’s Human Rights Chameleons: Geneva’s Human Rights Chameleons: Who Are They, How Do They Operate? 2 Geneva’s Human Rights Chameleons: Who Are They, How Do They Operate? Geneva’s Human Rights Chameleons: Geneva’s Human Rights Chameleons: Who Are They, How Do They Operate? First Published: February 2014 Published by: Research & Monitoring Division Department of Government Information, Sri Lanka Published by: Research & Monitoring Division Department of Government Information, Sri Lanka Design & Printing Layout by Media Tec Advertising & Printing Services Printed by: Department of Government Printing, Sri Lanka. 4 Who Are They, How Do They Operate? Contents Introduction 7 The Context 10 Background 15 LTTE’s New Networks 20 The Future 36 Conclusion 40 5 Geneva’s Human Rights Chameleons: Evolution of Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) International Network Source from: Ministry of Defence and Urban Development http://www.defence.lk/warcrimes/LTTE_international_network.html 6 Geneva’s Human Rights Chameleons: Who Are They, How Do They Operate? Introduction: The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in Sri Lanka was militarily dismantled in the May of 2009. To survive and revive, the LTTE’s international network that supported the three-decade terrorist and guerrilla campaign was forced to transform. Throughout largely in the West, conducted a relentless campaign of propaganda the conflict years in Sri Lanka, the LTTE network operating overseas, and misinformation against the Sri Lankan state, and was involved in fundraising and the procurement and shipping of weapons and equipment for the terrorist movement in Sri Lanka. Today, the very same individuals and entities that supported the ruthless killing, maiming and injuring of civilians and security forces personnel in Sri Lanka, have reinvented themselves. -

Bargaining in a Labor Regime: Plantation Life and the Politics of Development in Sri Lanka Mythri Jegathesan Submitted in Parti

! Bargaining in a Labor Regime: Plantation Life and the Politics of Development in Sri Lanka Mythri Jegathesan Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! © 2013! ! Mythri Jegathesan All rights reserved ! ! ABSTRACT Bargaining in a Labor Regime: Plantation Life and the Politics of Development in Sri Lanka Mythri Jegathesan This dissertation is an ethnographic study of migrant labor, development, and gender among Malaiyaha (“Hill Country”) Tamil tea plantation residents in contemporary Sri Lanka. It draws on one year of field research (2008-2009) conducted during state emergency rule in Sri Lanka amongst Malaiyaha Tamil plantation residents, migrant laborers, and community members responding to histories of dislocation and ethnic marginalization. Based on ethnographic observations, detailed life histories, and collaborative dialogue, it explores how Malaiyaha Tamils reconstitute what it means to be a political minority in an insecure Sri Lankan economy and state by 1) employing dignity-enabling strategies of survival through ritual practices and storytelling; 2) abandoning income-generating options on the plantations to ensure financial security; and 3) seeking radical alternatives to traditional development through employment of rights- based ideologies and networks of solidarity in and beyond Sri Lanka. Attending to these three spheres of collective practice—plantation life, migrant labor experience, and human development—this dissertation examines how Malaiyaha Tamils actively challenge historical representations of bonded labor and political voicelessness in order to rewrite their representative canon in Sri Lanka. ! ! At the center of each pragmatic site is the Malaiyaha Tamil woman. -

Annexure 1B 18416

Annexure 1 B List of taxpayers allotted to State having turnover of more than or equal to 1.5 Crore Sl.No Taxpayers Name GSTIN 1 BROTHERS OF ST.GABRIEL EDUCATION SOCIETY 36AAAAB0175C1ZE 2 BALAJI BEEDI PRODUCERS PRODUCTIVE INDUSTRIAL COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED 36AAAAB7475M1ZC 3 CENTRAL POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE 36AAAAC0268P1ZK 4 CO OPERATIVE ELECTRIC SUPPLY SOCIETY LTD 36AAAAC0346G1Z8 5 CENTRE FOR MATERIALS FOR ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY 36AAAAC0801E1ZK 6 CYBER SPAZIO OWNERS WELFARE ASSOCIATION 36AAAAC5706G1Z2 7 DHANALAXMI DHANYA VITHANA RAITHU PARASPARA SAHAKARA PARIMITHA SANGHAM 36AAAAD2220N1ZZ 8 DSRB ASSOCIATES 36AAAAD7272Q1Z7 9 D S R EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY 36AAAAD7497D1ZN 10 DIRECTOR SAINIK WELFARE 36AAAAD9115E1Z2 11 GIRIJAN PRIMARY COOPE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED ADILABAD 36AAAAG4299E1ZO 12 GIRIJAN PRIMARY CO OP MARKETING SOCIETY LTD UTNOOR 36AAAAG4426D1Z5 13 GIRIJANA PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED VENKATAPURAM 36AAAAG5461E1ZY 14 GANGA HITECH CITY 2 SOCIETY 36AAAAG6290R1Z2 15 GSK - VISHWA (JV) 36AAAAG8669E1ZI 16 HASSAN CO OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCERS SOCIETIES UNION LTD 36AAAAH0229B1ZF 17 HCC SEW MEIL JOINT VENTURE 36AAAAH3286Q1Z5 18 INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISER COOPERATIVE LIMITED 36AAAAI0050M1ZW 19 INDU FORTUNE FIELDS GARDENIA APARTMENT OWNERS ASSOCIATION 36AAAAI4338L1ZJ 20 INDUR INTIDEEPAM MUTUAL AIDED CO-OP THRIFT/CREDIT SOC FEDERATION LIMITED 36AAAAI5080P1ZA 21 INSURANCE INFORMATION BUREAU OF INDIA 36AAAAI6771M1Z8 22 INSTITUTE OF DEFENCE SCIENTISTS AND TECHNOLOGISTS 36AAAAI7233A1Z6 23 KARNATAKA CO-OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCER\S FEDERATION -

'Terrorism' Or

ISSN 2334-3745 Volume XII, Issue 2 April 2018 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 12, Issue 2 Table of Contents Welcome from the Editors Articles ‘Terrorism’ or ‘Liberation’? Towards a Distinction: A Case Study of the Armed Strug- gle of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE)....................................................1 by Muttukrishna Sarvananthan Tackling Terrorism’s Taboo: Shame..........................................................................19 by Matthew Kriner Spaces, Ties, and Agency: The Formation of Radical Networks................................32 by Stefan Malthaner Headhunting among Extremist Organizations: An Empirical Assessment of Talent Spotting...................................................................................................................44 by Gina Ligon, Michael Logan and Steven Windisch Policy Brief Interview with Max Hill, QC, Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation for the United Kingdom.......................................................................................................63 conducted by Sam Mullins Research Notes Erdogan's Turkey and the Palestinian Issue........................................................................................................................74 by Ely Karmon & Michael Barak 130+ (Counter-) Terrorism Research Centres – an Inventory...................................86 compiled and selected by Teun van Dongen Book Reviews Ronen Bergman. Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel’s Targeted Assassinations. New York: Random -

Managing Group Grievances and Internal Conflict: Sri Lanka Country Report

Working Paper Series Working Paper 13 Managing Group Grievances and Internal Conflict: Sri Lanka Country Report G.H. Peiris and K.M. de Silva Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ Conflict Research Unit June 2003 Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ Clingendael 7 2597 VH The Hague P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague Phonenumber: # 31-70-3245384 Telefax: # 31-70-3282002 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl/cru © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyrightholders. Clingendael Institute, P.O. Box 93080, 2509 AB The Hague, The Netherlands. Foreword This paper has been written within the framework of the research project ‘Managing Group Grievances and Internal Conflict’*, executed at the request of the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The project focuses on the process of, and motives for, (violent) group mobilisation and aims at the development of an analytical tool to assist policy-makers in designing conflict-sensitive development activities. In the course of the project, a preliminary assessment tool has been developed in cooperation with Dr. Michael Lund, and discussed with the researchers who carried out the assessment in four country cases: Ghana, Mozambique, Nicaragua and Sri Lanka. On the basis of this testing phase, the tool has been substantially amended and refined**. The present report, which was finalized in September 2002, results from the testing phase and reflects the structure of the analytical tool in its original form. -

"Les Tomouls De Sri Lanka Comptent Sui I'tide Mauricienne Les Tamonls Da Sri Dangers Qui Menacent Ses Tiques Et Ecoles Incendiees— Aide Aux Refugies

www.tamilarangam.net DMA MAHESWARAN IN MAURITIUS REPORTS FROM THE MAURITIUS PRESS ETMiiitant Lundi 23 Janvier 198^ Itfaftes/warai, leader do PLOTE en visile a Maurice "les Tomouls de Sri Lanka comptent sui I'tide mauricienne Les Tamonls da Sri dangers qui menacent ses tiques et ecoles incendiees— aide aux refugies. M. David Lanka, Tktimes des atro- correligionnaires. Le gou- il y eu aussi la tentative a raconte avec force details, dtes perpetrees par le vernement Sri Lankais a d'enlever a quelque un comment en septembre gQHYernement de M. Joliaa augment^ sensiblement son million da laboureurs leur 1983,alors qu'il 6tait d6tena Jayawardene comptent bean- budget pour la defense et droit de vote. avec d'autres militants coop sur le sootien des partis s'est assure de la collabora- depuis avril, il parvint & politiqnes et do people man- tion de certains pays afin M. Mabeshwaran a par!6 organiser Invasion de quel- ricienpoor mettre a tenne de pouvoir 'mieux brutali- en tenne £mu des 6meutes que 250 membres du PLOTE one sitoation qni commence ser, terroriser et assassicer de 1977, 1981 et juillet 1983. d'une prison. II a fait £tat a devenir insupportable. les Tamouls'. «Ces Smeutes avaient £t£ des attaques de la police et Cette declaration a etc planifides et execut^es par le de 1'armee sur les biens de faite hier apres-midi par SelonM Maheshwaran les gouvernement pour encou- la «Gandhiyam Sociefy» — M. Usss Mahss&wasaE, lea- £tudiants cisgalais recoivent rager 1'assassinat, le viol, et locaux, meubles, v^hicules, der do People's Liberation une formation militaire a le matraquage d'un peuple plantations aussi bien que Organisation of Tamil I'&ole, tandis qu'un mi- sans moyen de se defendre.