FOMC Meeting Transcript, September 12-13, 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pricing*, Pool and Payment** Due Dates January - December 2021 Mideast Marketing Area Federal Order No

Pricing*, Pool and Payment** Due Dates January - December 2021 Mideast Marketing Area Federal Order No. 33 Class & Market Administrator Payment Dates for Producer Milk Component Final Pool Producer Advance Prices Payment Dates Final Payment Due Partial Payment Due Pool Month Prices Release Date Payrolls Due & Pricing Factors PSF, Admin., MS Cooperative Nonmember Cooperative Nonmember January February 3 * February 13 February 22 December 23, 2020 February 16 ** February 16 February 17 Janaury 25 January 26 February March 3 * March 13 March 22 January 21 * March 15 March 16 March 17 February 25 February 26 March March 31 * April 13 April 22 February 18 * April 15 April 16 April 19 ** March 25 March 26 April May 5 May 13 May 22 March 17 * May 17 ** May 17 ** May 17 April 26 ** April 26 May June 3 * June 13 June 22 April 21 * June 15 June 16 June 17 May 25 May 26 June June 30 * July 13 July 22 May 19 * July 15 July 16 July 19 ** June 25 June 28 ** July August 4 * August 13 August 22 June 23 August 16 ** August 16 August 17 July 26 ** July 26 August September 1 * September 13 September 22 July 21 * September 15 September 16 September 17 August 25 August 26 September September 29 * October 13 October 22 August 18 * October 15 October 18 ** October 18 ** September 27 ** September 27 ** October November 3 * November 13 November 22 September 22 * November 15 November 16 November 17 October 25 October 26 November December 1 * December 13 December 22 October 20 * December 15 December 16 December 17 November 26 ** November 26 December January 5, 2022 January 13, 2022 January 22, 2022 November 17 * January 18, 2022 ** January 18, 2022 ** January 18, 2022 ** December 27 ** December 27 ** * If the release date does not fall on the 5th (Class & Component Prices) or 23rd (Advance Prices & Pricing Factors), the most current release preceding will be used in the price calculation. -

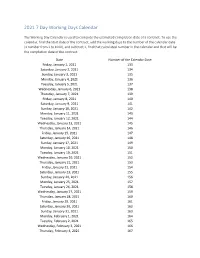

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

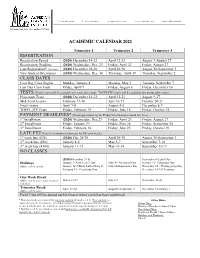

Academic Calendar 2021 Registration Class Dates

T: 214.352.0582 F: 214.350.4119 [email protected] www.alidallas.edu DAL214F01280000 1505 Luna Road, Suite 150, Carrollton, TX 75006 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2021 Trimester 1 Trimester 2 Trimester 3 REGISTRATION Registration Period (2020) December 14-23 April 12-23 August 9-August 27 Registration Deadline (2020) Wednesday, Dec. 23 Friday, April 23 Friday, August 27 Late Registration* (late fees) (2020) December 28-30 April 26-30 August 30-September 3 New Student Orientation (2020) Wednesday, Dec. 30 Thursday, April 29 Thursday, September 2 CLASS DATES First Day Class Begins Monday, January 4 Monday, May 3 Tuesday, September 7 Last Day Class Ends Friday, April 9 Friday, August 6 Friday, December 10 TESTS (Exam scores will be available one week after exam. TOEFL-ITP scores will be available two weeks after exam.) Placement Tests (2020) December 14-23 April 12-23 August 9-27 Mid-Term Exams February 17-18 June 16-17 October 20-21 Final Exams April 7-8 August 4-5 December 8-9 TOEFL-ITP Exam Friday, February 19 Friday, June 18 Friday, October 22 PAYMENT DEADLINES* (Please pay tuition by the Friday listed below to avoid late fees.) 1st Installment (2020) Wednesday, Dec.23 Friday, April 23 Friday, August 27 2nd Installment Friday, January 29 Friday, May 28 Friday, September 24 3rd Installment Friday, February 26 Friday, June 25 Friday, October 29 LATE FEE (Late fees continue to increase by $50 each week.) 1st week late ($25) (2020) Dec 28-30 April 26-30 August 30-September 3 2nd week late ($50) January 4-8 May 3-7 September 7-10 3rd week late ($100) January 11-15 May 10-14 September 13-17 NO CLASSES (2020) December 31 & September 6-Labor Day Holidays January 1- New Year’s Day May 31- Memorial Day October 11- Columbus Day (Office will be closed) January 18- Martin Luther King Jr. -

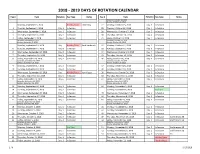

2018 - 2019 Days of Rotation Calendar

2018 - 2019 DAYS OF ROTATION CALENDAR Day # Date Rotation Day Type Notes Day # Date Rotation Day Type Notes Saturday, October 13, 2018 Sunday, October 14, 2018 Monday, September 3, 2018 Holiday/Vaca Labor Day 27 Monday, October 15, 2018 Day 3 In Session 1 Tuesday, September 4, 2018 Day 1 In Session 28 Tuesday, October 16, 2018 Day 4 In Session 2 Wednesday, September 5, 2018 Day 2 In Session 29 Wednesday, October 17, 2018 Day 5 In Session 3 Thursday, September 6, 2018 Day 3 In Session 30 Thursday, October 18, 2018 Day 6 In Session 4 Friday, September 7, 2018 Day 4 In Session 31 Friday, October 19, 2018 Day 1 In Session Saturday, September 8, 2018 Saturday, October 20, 2018 Sunday, September 9, 2018 Sunday, October 21, 2018 Monday, September 10, 2018 Day Holiday/Vaca Rosh Hashanah 32 Monday, October 22, 2018 Day 2 In Session 5 Tuesday, September 11, 2018 Day 5 In Session 33 Tuesday, October 23, 2018 Day 3 In Session 6 Wednesday, September 12, 2018 Day 6 In Session 34 Wednesday, October 24, 2018 Day 4 In Session 7 Thursday, September 13, 2018 Day 1 In Session 35 Thursday, October 25, 2018 Day 5 In Session 8 Friday, September 14, 2018 Day 2 In Session 36 Friday, October 26, 2018 Day 6 In Session Saturday, September 15, 2018 Saturday, October 27, 2018 Sunday, September 16, 2018 Sunday, October 28, 2018 9 Monday, September 17, 2018 Day 3 In Session 37 Monday, October 29, 2018 Day 1 In Session 10 Tuesday, September 18, 2018 Day 4 In Session 38 Tuesday, October 30, 2018 Day 2 In Session Wednesday, September 19, 2018 Day Holiday/Vaca Yom Kippur 39 Wednesday, October 31, 2018 Day 3 In Session 11 Thursday, September 20, 2018 Day 5 In Session 40 Thursday, November 1, 2018 Day 4 In Session 12 Friday, September 21, 2018 Day 6 In Session 41 Friday, November 2, 2018 Day 5 In Session Saturday, September 22, 2018 Saturday, November 3, 2018 Sunday, September 23, 2018 Sunday, November 4, 2018 13 Monday, September 24, 2018 Day 1 In Session 42 Monday, November 5, 2018 Day 6 In Session 14 Tuesday, September 25, 2018 Day 2 In Session Tuesday, November 6, 2018 Prof Dev. -

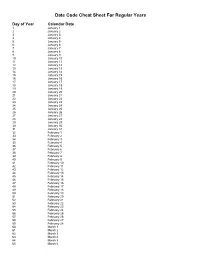

Julian Date Cheat Sheet for Regular Years

Date Code Cheat Sheet For Regular Years Day of Year Calendar Date 1 January 1 2 January 2 3 January 3 4 January 4 5 January 5 6 January 6 7 January 7 8 January 8 9 January 9 10 January 10 11 January 11 12 January 12 13 January 13 14 January 14 15 January 15 16 January 16 17 January 17 18 January 18 19 January 19 20 January 20 21 January 21 22 January 22 23 January 23 24 January 24 25 January 25 26 January 26 27 January 27 28 January 28 29 January 29 30 January 30 31 January 31 32 February 1 33 February 2 34 February 3 35 February 4 36 February 5 37 February 6 38 February 7 39 February 8 40 February 9 41 February 10 42 February 11 43 February 12 44 February 13 45 February 14 46 February 15 47 February 16 48 February 17 49 February 18 50 February 19 51 February 20 52 February 21 53 February 22 54 February 23 55 February 24 56 February 25 57 February 26 58 February 27 59 February 28 60 March 1 61 March 2 62 March 3 63 March 4 64 March 5 65 March 6 66 March 7 67 March 8 68 March 9 69 March 10 70 March 11 71 March 12 72 March 13 73 March 14 74 March 15 75 March 16 76 March 17 77 March 18 78 March 19 79 March 20 80 March 21 81 March 22 82 March 23 83 March 24 84 March 25 85 March 26 86 March 27 87 March 28 88 March 29 89 March 30 90 March 31 91 April 1 92 April 2 93 April 3 94 April 4 95 April 5 96 April 6 97 April 7 98 April 8 99 April 9 100 April 10 101 April 11 102 April 12 103 April 13 104 April 14 105 April 15 106 April 16 107 April 17 108 April 18 109 April 19 110 April 20 111 April 21 112 April 22 113 April 23 114 April 24 115 April -

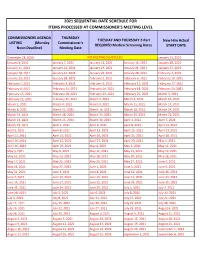

2021 Sequential Date List

2021 SEQUENTIAL DATE SCHEDULE FOR ITEMS PROCESSED AT COMMISSIONER'S MEETING LEVEL COMMISSIONERS AGENDA THURSDAY TUESDAY AND THURSDAY 2-Part New Hire Actual LISTING (Monday Commissioner's REQUIRED Medical Screening Dates START DATE Noon Deadline) Meeting Date December 28, 2020 NO MEETING SCHEDULED January 13, 2021 January 4, 2021 January 7, 2021 January 12, 2021 January 14, 2021 January 20, 2021 January 11, 2021 January 14, 2021 January 19, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 27, 2021 January 18, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 26, 2021 January 28, 2021 February 3, 2021 January 25, 2021 January 28, 2021 February 2, 2021 February 4, 2021 February 10, 2021 February 1, 2021 February 4, 2021 February 9, 2021 February 11, 2021 February 17, 2021 February 8, 2021 February 11, 2021 February 16, 2021 February 18, 2021 February 24, 2021 February 15, 2021 February 18, 2021 February 23, 2021 February 25, 2021 March 3, 2021 February 22, 2021 February 25, 2021 March 2, 2021 March 4, 2021 March 10, 2021 March 1, 2021 March 4, 2021 March 9, 2021 March 11, 2021 March 17, 2021 March 8, 2021 March 11, 2021 March 16, 2021 March 18, 2021 March 24, 2021 March 15, 2021 March 18, 2021 March 23, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 31, 2021 March 22, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 30, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 7, 2021 March 29, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 6, 2021 April 8, 2021 April 14, 2021 April 5, 2021 April 8, 2021 April 13, 2021 April 15, 2021 April 21, 2021 April 12, 2021 April 15, 2021 April 20, 2021 April 22, 2021 April 28, 2021 April 19, 2021 April 22, 2021 April 27, 2021 April -

Local Law 59: Report for Week of September 7, 2020 - September 13, 2020

Local Law 59: Report for Week of September 7, 2020 - September 13, 2020 1 I. Table of Contents I. Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 II. Data Dictionary ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 III. Data Tables ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 2 II. Data Dictionary # Weekly Report Metrics Definition Source Number of individuals (incarceration-level) in the care of and tested for COVID-19 infection by CHS and reported by date of test result or date test result was pending from March 13, 2020 to the last day of the current report week. Total tests disaggregated by positive, negative, and pending result status are reported from March 13, 2020 onwards. Individuals who Number of individuals tested for infection, by positive, test negative and are reported as such on one -

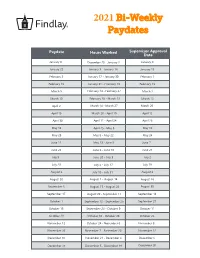

2021 Bi-Weekly Paydates

2021 Bi-Weekly Paydates Paydate Hours Worked Supervisor Approval Date January 8 December 20 - January 2 January 4 January 22 January 3 - January 16 January 15 February 5 January 17 - January 30 February 1 February 19 January 31 - February 13 February 15 March 5 February 14 - February 27 March 1 March 19 February 28 - March 13 March 15 April 2 March 14 - March 27 March 29 April 16 March 28 - April 10 April 12 April 30 April 11 - April 24 April 26 May 14 April 25 - May 8 May 10 May 28 May 9 - May 22 May 24 June 11 May 23 - June 5 June 7 June 25 June 6 - June 19 June 21 July 9 June 20 - July 3 July 2 July 23 July 4 - July 17 July 19 August 6 July 18 - July 31 August 2 August 20 August 1 - August 14 August 16 September 3 August 15 - August 28 August 30 September 17 August 29 - September 11 September 13 October 1 September 12 - September 25 September 27 October 15 September 26 - October 9 October 11 October 29 October 10 - October 23 October 25 November 12 October 24 - November 6 November 8 November 26 November 7 - November 20 November 22 December 10 November 21 - December 4 December 6 December 24 December 5 - December 18 December 20 2021 Bi-Weekly Paydate/Holiday Paydates January February March April Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 3 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 -

Pay Date Calendar

Pay Date Information Select the pay period start date that coincides with your first day of employment. Pay Period Pay Period Begins (Sunday) Pay Period Ends (Saturday) Official Pay Date (Thursday)* 1 January 10, 2016 January 23, 2016 February 4, 2016 2 January 24, 2016 February 6, 2016 February 18, 2016 3 February 7, 2016 February 20, 2016 March 3, 2016 4 February 21, 2016 March 5, 2016 March 17, 2016 5 March 6, 2016 March 19, 2016 March 31, 2016 6 March 20, 2016 April 2, 2016 April 14, 2016 7 April 3, 2016 April 16, 2016 April 28, 2016 8 April 17, 2016 April 30, 2016 May 12, 2016 9 May 1, 2016 May 14, 2016 May 26, 2016 10 May 15, 2016 May 28, 2016 June 9, 2016 11 May 29, 2016 June 11, 2016 June 23, 2016 12 June 12, 2016 June 25, 2016 July 7, 2016 13 June 26, 2016 July 9, 2016 July 21, 2016 14 July 10, 2016 July 23, 2016 August 4, 2016 15 July 24, 2016 August 6, 2016 August 18, 2016 16 August 7, 2016 August 20, 2016 September 1, 2016 17 August 21, 2016 September 3, 2016 September 15, 2016 18 September 4, 2016 September 17, 2016 September 29, 2016 19 September 18, 2016 October 1, 2016 October 13, 2016 20 October 2, 2016 October 15, 2016 October 27, 2016 21 October 16, 2016 October 29, 2016 November 10, 2016 22 October 30, 2016 November 12, 2016 November 24, 2016 23 November 13, 2016 November 26, 2016 December 8, 2016 24 November 27, 2016 December 10, 2016 December 22, 2016 25 December 11, 2016 December 24, 2016 January 5, 2017 26 December 25, 2016 January 7, 2017 January 19, 2017 1 January 8, 2017 January 21, 2017 February 2, 2017 2 January -

COVID-19 Dashboard- Sunday, September 13, 2020 Dashboard of Public Health Indicators

9/13/2020 Public Health Indicators Massachusetts Department of Public Health COVID-19 Dashboard- Sunday, September 13, 2020 Dashboard of Public Health Indicators Newly Reported Total Confirmed Newly Reported Total Deaths Confirmed Cases Cases Deaths among among Confirmed Today Confirmed Today Cases 267 122,904 14 9,001 New Individuals Total Individuals Below is the current status: Tested by Tested by Molecular Tests Molecular Tests Measure Status 12,102 1,956,033 COVID-19 positive test rate ⚫ Number of individuals who died from COVID-19 ⚫ Total Molecular Legend Number of patients with COVID-19 in hospitals ⚫ Tests Healthcare system readiness ⚫ Administered Testing capacity ⚫ 3,006,158 Contact tracing capabilities ⚫ The front page of the dashboard has been reformatted. Antibody tests (individual and total numbers) can be found on page 18. 1 1/1 9/13/2020 Public Health Indicators2 Massachusetts Department of Public Health COVID-19 Dashboard- Sunday, September 13, 2020 Percent or Count of Change Since Dashboard of Public Health Indicators Lowest Observed Value (LOV) 7 Day Weighted 1.5% 1.4% 1.4% 1.3% 1.3% Average of Positive 1.2% 1.2% 1.4% 1.4% 1.2% 1.1% 1.1% 1.1% 1.0% 0 % Molecular Test Rate* 1.0% 1.0% 1.0% 1.0% 1.0% 0.9% 0.9% 0.9% 0.9% 0.9% 0.9% 0.9% 0.9% 0.9% 1.0% 0.9% 0.8% 0.8% 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 August September LOV =0.8% 3 Day Average of 400 371 371 370 Number of COVID- 391 382 353 350 369 336 339 334 340 341 339 19 Patients in 330 323 323 329 7 % 317 313 317 317 314 313 -

September 13, 2019

SEPTEMBER 13, 2019 UPCOMING o Saturday, September 14, 10:00 AM – 12:00 PM - Points of Information Distribution Demonstration – City Hall o Monday, September 16, 6:30 PM – Planning Commission Meeting - City Hall o Tuesday, September 17, 8:30 AM – Las Virgenes-Malibu COG Meeting – Agoura Hills City Hall o Wednesday, September 18, 7:00 PM – Malibu Library Speaker Series "Deconstructing the Beatles' Abbey Road" with Scott Freiman – City Hall o Thursday, September 19, 6:00 PM - Fire Safe Council - City Hall HOW TO REACH THE CITY DURING EMERGENCIES The City encourages all community residents to sign up for emergency, traffic, weather and utility alerts through the website e-notification system at MalibuCity.org/News (scroll down to "Alert Center"). You can also get emergency information during a disaster by phone by calling the City’s Hotline at 310-456-9982. During an emergency situation, the Hotline is updated regularly with current information. ONE CALL TO CITY HALL – 310-456-CITY, EXTENSION 311 One Call to City Hall is available 24 hours a day/7 days a week for community members to report issues or contact City staff during non-business hours. For life-threatening emergencies, please call 911. PCH – PAVEMENT PROJECT (CALTRANS) This Caltrans project consists of making pavement repairs and applying a slurry seal treatment on Pacific Coast Highway from the McClure Tunnel in Santa Monica to the Malibu Lagoon Bridge.Caltrans will close one lane of PCH from Tuesday, September 17 through October 17, between 8:00 PM and 6:00 AM for the work. SEPTEMBER -

COVID-19 Update September 14, 2020

COVID-19 Update September 14, 2020 As of September 13, 2020, at 8:30 PM, the total of laboratory-confirmed and probable COVID-19 cases reported among Connecticut residents is 54895, including 52624 laboratory-confirmed and 2271 probable cases. Sixty-four patients are currently hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19. There have been 4485 COVID-19-associated deaths. In Connecticut during the early months of this pandemic, it became increasingly clear that it would be necessary to track probable COVID-19 cases and deaths, in addition to laboratory-confirmed (RT-PCR) cases and deaths. This was needed to better measure the burden and impact of this disease in our communities and is now part of the national surveillance case definition for COVID-19. Probable cases of COVID-19 involve persons who have not had confirmatory laboratory testing (RT-PCR) performed for COVID-19, but whose symptoms indicate they are likely to have a COVID-19 infection. In Connecticut, most of the probable COVID-19 cases involve persons whose death certificates list COVID-19 disease or SARS-CoV-2 as a cause of death or a significant condition contributing to death. Prior to June 1, probable and confirmed cases were reported together. Overall Summary Total** Change Since Friday COVID-19 Cases 54895 +569 COVID-19-Associated Deaths 4485 +5 Patients Currently Hospitalized with COVID-19 64 +13 COVID-19 PCR Tests Reported 1377717 +48964 **Includes confirmed plus probable cases COVID-19 Cases and Associated Deaths by County of Residence As of 09/13/20 8:30pm. COVID-19