Jasper-Jones-Learning-Resources.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walk in the Footsteps of Jasper Jones

ABOUT THE FILM Jasper Jones is the story of Charlie Bucktin, a bookish boy of 14 living in a small town in Western Australia. In the dead of night during the scorching summer of 1969, Charlie is startled when he is woken by local mixed-race outcast Jasper Jones outside his window. Jasper leads him deep into the forest and shows him something that will change his life forever, setting them both on a dangerous journey to solve a mystery that will consume the entire community. The movie is adapted from Craig Silvey’s best- DID YOU KNOW? selling Australian novel, directed by Rachel Perkins and features a stellar cast including Jasper Jones author and screenwriter Toni Collette, Hugo Weaving, Levi Miller, Craig Silvey was on set each day during Angourie Rice, Dan Wyllie and Aaron McGrath. It is distributed by Madman Entertainment. filming, providing valuable input into the making of the movie. For more information, visit www.jasperjonesfilm.com COMMUNITY SPIRIT The people of Pemberton really embraced the invitation to be involved in the filming of Jasper Jones, with residents offering up their homes, their cars and even themselves. Many locals were used as extras or background actors in the film, jumping at the chance to play citizens of Corrigan. The remote location, about 330 kilometres from the state capital of Perth, helped to foster a sense of community between the film set and residents. WALK IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF Says cinematographer Mark Wareham, “When I look at scenes now, I can see my mate who worked at the local bottle shop, and the guy that ran the local store. -

JASPER JONES a Film by Rachel Perkins

Presents JASPER JONES A film by Rachel Perkins “A marvelously entertaining and ultimately uplifting tale” – Richard Kuipers, Variety Austrailia / 2017 / Drama / English / 103 mins Film Movement Contact: Press: [email protected] Theatrical: Clemence Taillandier | (212) 941-7744 x301 | [email protected] Festivals & Non-Theatrical: Maxwell Wolkin | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] www.FilmMovement.com 1 SYNOPSIS Adapted from Craig Silvey’s best-selling Australian novel and featuring a stellar cast including Toni Collette, Hugo Weaving, Levi Miller, Angourie Rice, Dan Wyllie and Aaron McGrath, JASPER JONES is the story of Charlie Bucktin, a bookish boy of 14 living in a small town in Western Australia. In the dead of night during the scorching summer of 1969, Charlie is startled when he is woken by local mixed-race outcast Jasper Jones outside his window. Jasper leads him deep into the forest and shows him something that will change his life forever, setting them both on a dangerous journey to solve a mystery that will consume the entire community. In an isolated town where secrecy, gossip and tragedy overwhelm the landscape, Charlie faces family breakdown, finds his first love, and discovers what it means to be truly courageous. SHORT SYNOPSIS Based on the best-selling novel, JASPER JONES is the story of Charlie Bucktin, a young bookish boy living in a small town. One night, local mixed-race outcast Jasper Jones appears at Charlie’s window and the pair embark on a journey to solve a mystery that will consume the entire community. LOGLINE Two boys journey to solve a mystery that will consume the entire community. -

Jasper Jones Study Guide

STATE THEATRE COMPANY SOUTH AUSTRALIA AND FLINDERS UNIVERSITY PRESENT Jasper Jones BASED ON THE BOOK BY CRAIG SILVEY ADAPTED BY KATE MULVANY Study with State SYNOPSIS Set in 1965, Jasper Jones is a coming-of-age story narrated by 13-year-old Charlie Bucktin and taking place in Corrigan, a fictional small town in Western Australia. Charlie begins to investigate and challenge the world he has grown up in after he is visited one night by town scapegoat Jasper Jones. With an Aboriginal mother and a white father, Jasper is labelled a “half-caste” and is blamed whenever anything goes wrong in Corrigan. He approaches Charlie for help after finding the body of local girl Laura Wishart. Together, Charlie and Jasper dispose of Laura’s body and attempt to discover who murdered her. For more, watch the trailer for the show online: statetheatrecompany.com.au/shows/jasper-jones DUNSTAN PLAYHOUSE / 16 AUGUST - 7 SEPTEMBER, 2019 RUNNING TIME Approximately 170 minutes (including 20 minute interval). SHOW WARNINGS Contains coarse language, adult themes, racism, theatrical weapons, references to violence and sexual abuse, and depictions of suicide that may be triggering to some audience members. Those affected by the themes in the production can seek support from: Lifeline: 13 11 44 Beyond Blue: 1300 224 636 Contents INTRODUCING THE PLAY Creative team ............................... 4-5 Adaptor’s note from Kate Mulvany .................................. 6 Director’s note from Nescha Jelk ............................... ...7 An interview with Nescha Jelk ............................... 8-9 A bit of background on Jasper Jones ................................ 10 What next? ................................. 11 CHARACTERS & CHARACTERISATION Cast Q&A: interviews ........................... 12-15 Action choreography ............................... -

Elebrate 2013!

The Barmera Summer Barmera Library & Council Customer Service Centre Newsletter 2013 elebrate 2013! HELLO 2013! Hope this year, the Chinese Year of READ IT! SNAP IT! Winners! the Water Snake, is a lucky one for you. Chinese Congratulations to the winners of our photo folklore says a Snake in the house is a good omen— competition held in November and December 2012. So DON‘T PANIC if you see one this summer. Adult Section Winner: If you were born in the Year of the Snake -1929, 1941, 1953, 1965, 1977, 1989, 2001 and 2013, you are intelligent, wise, and lucky in business, so this could be a special year! GOODBYE 2012! The National Year of Reading has ended—but that‘s no reason to stop reading! New books are coming in all the time at Barmera Library, so look for the shiny silver ―NEW Helen Burgemeister’s 2013‖ stickers like the one at the top of this page. “Peacock eye” won her a The website www.love2read.org.au will continue. Kindle Touch Reader Keep checking this for reading guides and events, competitions, news and views about reading. Children’s Section Winner : THE YEAR OF ...MANY THINGS! 2013 has been declared the year of International Year of Water Co-operation International Year of Statistics Mathematics of Planet Earth European Year of Citizens So, if you are interested in Water Management, Statistics, Mathematics, and Europe then this will be the year for you! Libraries can be good starting points Jessica Price’s for research, and we are happy to help with your “Nanny in the garden” - enquiries. -

The Amber Amulet by Craig Silvey

BOOK PUBLISHERS Teachers’ Notes by Radhiah Chowdhury The Amber Amulet by Craig Silvey ISBN 9781925575125 (paperback) Recommended for ages 14 yrs and older These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. Introduction .......................................... 2 Themes ........................................ 2 Curriculum alignment ............................. 2 Activities for the classroom ...................... 3 Before reading ............................... 3 What is pulp fiction?..................... 3 What is superhero fiction? ............. 3 During reading .............................. 4 Chapter by chapter ...................... 4 After reading ................................. 7 Story and text structure ............... 7 Thematic study ........................... 8 Related Texts ....................................... 10 About the writer .................................... 11 83 Alexander Street PO Box 8500 Crows Nest, Sydney St Leonards NSW 2065 NSW 1590 ph: (61 2) 8425 0100 [email protected] Allen & Unwin PTY LTD Australia Australia fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 www.allenandunwin.com ABN 79 003 994 278 INTRODUCTION Dear Sir/Ma'am, Please find enclosed this AMBER AMULET. That must sound unusual to a citizen, but you will have to trust me on this count because the science is too detailed for me to outline here. All you need to know is that the AMBER AMULET will eliminate your unhappiness by counteracting it -

Craig Silvey’S Novel Jasper Jones, Is a Heart-Warming, Life-Affirming Coming-Of-Age Novel Set in Contemporary Western Australia

CREATIVE LEARNING RESOURCE LITERATURE LITERATURE & IDEAS FOR SECONDARY SCHOOLS MON 22 FEB 1 CONTENTS 2 Background 3 Authors & Activities 4 Attending Live Performance 5 Curriculum Links Perth Festival acknowledges the Noongar people who continue to practise their values, language, beliefs and knowledge on their kwobidak boodjar. They remain the spiritual and cultural birdiyangara of this place and we honour and respect their caretakers and custodians and the vital role Noongar people play for our community and our Festival to flourish. Acknowledgment developed by Associate Artist Kylie Bracknell with support from Perth Festival’s Noongar Advisory Circle (Vivienne Binyarn Hansen, Mitchella Waljin Hutchins, Carol Innes, Barry McGuire, Richard Walley OAM & Roma Yibiyung Winmar) BACKGROUND Explore the relationships between conventions and language (and how they change across genre with regards to audience and purpose), as authors Yuot A Alaak and Sophie McNeill give fascinating insight into their writing process. HONEYBEE Honeybee, the stunning follow-up to best-selling author Craig Silvey’s novel Jasper Jones, is a heart-warming, life-affirming coming-of-age novel set in contemporary Western Australia. Students will hear about Craig’s writing career, his inspiration for writing Honeybee and what he has in mind for his next project. FATHER OF THE LOST BOYS Yuot A Alaak’s memoir Father of the Lost Boys is a searing account of the author’s four-year journey across the deserts of Ethiopia and Sudan as one of the 20,000 now-famous child soldiers of Sudan – the Lost Boys – led by his father, Mecak Ajang Alaak. Yuot writes about the boys’ perilous crossing of the Nile, and finally reaching the safety of a Kenyan refugee camp. -

PERTH VOICE Gorman FEDERAL MEMBER for PERTH SEPTEMBER UPDATE

HON ALISON XAMON MLC The Perth Member for North Metropolitan Your Green Voice in Parliament o alisonxamon.org.au @alisonxamonmlc VN 1154 Saturdayoice October 3, 2020 • Phone 9430 7727 • www.perthvoice.com • [email protected] @alisonxamon Willing Council slammed for walkers wanted! THE school holidays will be over soon so let’s get back to lunch with developer work. We have paper with representatives from Paul Collins called out of interest that could lead compromise the city’s delivery areas to fill by ASTRID DAINTON AMP Capital – with WA the city’s hierarchy at to actual conflicts; it brings decision-making. in Northbridge and premier Mark McGowan the the council’s September into question impartiality But WA Party founder North Perth for a STIRLING mayor Mark keynote speaker. 8 meeting, saying it was and the ease of access and local government hard-working, special Irwin is under fire from AMP has a development inappropriate to have which developers have in expert Julie Matheson said couple. You’ll get residents after he and the application before Stirling accepted the invitation. getting to the three most under Stirling’s code of to meet all sorts of city’s two most senior for three high-density “Why anyone from local senior people at the City of conduct, the trio should colourful characters public servants shared towers on the site of the government would want to Stirling.” have knocked back the and business in a luncheon with the Karrinyup shopping centre, be on a developer’s table at But Mr Irwin defended invitation from AMP. -

Jasper Jones by Craig Silvey P 22 the Amber Amulet by Craig Silvey P 23 Paruku: the Desert Brumby by Jesse Blackadder

Zeitgeist Media Group is a unique literary agency founded in 2008 with an international outlook. We represent a distinctive array of Australian, American, British, European, Russian, Turkish and Chinese authors from our Sydney and Brussels offices. Our list includes bestsellers, the finest literary fiction, an iconic cartoonist, inspiring memoirs and thought-provoking non-fiction. We also represent picture books, middle grade and YA/crossover titles from around the world. Our passion is to connect authors, publishers and media across the globe. We hope you enJoy what we have to offer. Warm regards, Benython, Sharon and Thomasin www.zeitgeistagency.com/ Benython Oldfield Founding Director Australia Level 1, 142 Smith Street Sharon Galant Summer Hill, Sydney Founding Director Europe NSW, 2130 Australia Avenue de Fré 229, 3rd floor +61 2 8060 9715 1180 Brussels, Belgium [email protected] +32 479 262 843 [email protected] Thomasin Chinnery Children’s & YA Agent Avenue de Fré 229, 3rd floor 1180 Brussels, Belgium +32 474 055 696 [email protected] YOUNG ADULT p 5 The Coconut Children by Vivian Pham p 6 Jenny Was A Friend of Mine by Catherine E Kovach p 7 The Fourteenth Letter by Marc de Bel and Gino Marchal p 8 Hive and Rogue by AJ Betts (2-book series) MIDDLE GRADE p 10 On the Trail of Genghis Khan (Young Reader’s Edition) by Tim Cope p 11 Dream Riders by Jesse Blackadder and Laura Bloom p 12 The Little Wave by Pip Harry p 13 Become A Planet Agent by Eleni Andreadis CHAPTER BOOKS & PICTURE BOOKS p 15 Seagulls & Co. -

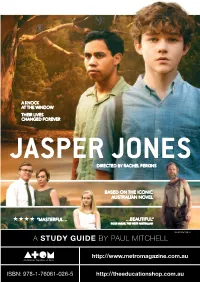

A Study Guide by Paul Mitchell

A KNOCK AT THE WINDOW THEIR LIVES CHANGED FOREVER DIRECTED BY RACHEL PERKINS BASED ON THE ICONIC AUSTRALIAN NOVEL HHHH …BEAUTIFUL“ “MASTERFUL… ROSS McRAE, THE WEST AUSTRALIAN © ATOM 2017 A STUDY GUIDE BY PAUL MITCHELL http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-76061-026-5 http://theeducationshop.com.au Jasper Jones A knock at a boy’s window changes two lives forever. Directed by Rachel Perkins (Bran Nue Day, Radiance), Jasper Jones (2017) is an adaptation of Craig Silvey’s popular and successful eponymous 2009 novel. It’s the story of Charlie Bucktin, a book- ish 14-year-old boy living in a small town in Western Australia in the late 1960s. His adventures with Jasper Jones, an older Aboriginal boy with a mysterious past and potentially dangerous future, make Charlie grow up fast and find courage he didn’t know he possessed. CONTENT HYPERLINKS 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 3 SYNOPSIS 5 ABOUT THE DIRECTOR: RACHEL PERKINS 6 MAKING JASPER JONES 8 THE CAST 9 THEMES IN JASPER JONES 11 ADAPTING JASPER JONES 14 JASPER JONES: QUESTIONING OUR HISTORY 14 KEY SCENES: CLOSE STUDY © ATOM 2017 © ATOM 15 RESOURCES 15 QUESTIONS 2 Classification: M Length: 105 mins Curriculum Links Jasper Jones is suitable for students in Years 10 to 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, History, Literature and Media. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australi- ancurriculum.edu.au/ as well as curriculum outlines relevant to these subjects in their state or territory. English, Literature and Media students are expected to discuss the meaning derived from texts, the relationship between them, the contexts in which texts are produced and read, and the experiences the reader brings to them. -

Title Author Format

Format Title Author LP = 1 Large Print copy A = 1 Audiobook copy Actress Anne Enright Addition Toni Jordan A A dog’s purpose W. Bruce Cameron LP A god in ruins Kate Atkinson A All the light we cannot see Anthony Doerr LP A American dirt Jeanine Cummins LP A Amsterdam Ian McEwan And the mountains echoed Khaled Hosseini LP A Apeirogon Colum McCann Any human heart William Boyd Any ordinary day Leigh Sales LP A A spool of blue thread Anne Tyler A Atlas of unknowns Tania James The Auschwitz violin Maria Angels Anglada Belly dancing for beginners Liz Byrski Big brother Lionel Shriver A Big little lies Liane Moriarty LP A Black swan green David Mitchell The Bolter Frances Osborne The Book of Two Ways Jodi Picoult LP A The book thief Markus Zusak The borrower Rebecca Makkai The boy in the striped pyjamas John Boyne Boy swallows universe Trent Dalton LP A Boycott Lisa Forrest Breath Tim Winton Bring up the bodies Hilary Mantel Burial rites Hannah Kent LP A Cast iron Peter May The cat’s table Michael Ondaatje The chocolate tin Fiona McIntosh LP A Company of liars Karen Maitland A 1 Format Title Author LP = 1 Large Print copy A = 1 Audiobook copy Crimson dawn Fleur McDonald LP Curious incident of the dog in the Mark Haddon night-time Cutting for stone Abraham Verghese Dark emu Bruce Pascoe LP A The daughters of Mars Tomas Keneally LP A Dewey Vicki Myron LP The dictionary of lost words Pip Williams LP A Dog boy Eva Hornung Dovekeepers Alice Hoffman The drowning girl Margaret Leroy The dry Jane Harper LP A Eggshell skull Bri Lee LP The elegance of a hedgehog Muriel Barbery The elephant keeper Christopher Nicholson Erotic stories for Punjabi widows B.K. -

Book Club Book of the Month July 2021 Locust Summer by David Allan-Petale (Fremantle Press)

Book Club Book of the Month July 2021 Locust Summer by David Allan-Petale (Fremantle Press) Summary On the cusp of Summer in 1986, Rowan Brockman is working as a journalist in the City of Perth. When his mother calls to ask if he will come home to Septimus in the Western Australian Wheatbelt to help with the harvest, Rowan is torn. His brother Albert, the natural heir to the farm, has died, and Rowan’s father’s health is failing after a dementia diagnosis. Although he longs to, when his mother drops the news that she is selling the farm that has been in the family for three generations, Rowan knows there is no way he can refuse the request. A mix of family obligation, nostalgia and duty draw him back to the world of his youth, where Rowan will face old acquaintances, forgotten memories, grief, and love. This is the story of one man’s final harvest, in a place he does not want to be, and being given one last chance to make peace before the past, and those he has loved, disappear. About the Author David Allan-Petale is a writer living between bush and sea north of Perth, Western Australia. He worked for many years as a journalist in WA with the ABC and internationally with BBC World News in London. David is a father, sailor, and traveller, a man who has a yarn with everyone and likes to share whisky over good conversation. He is a supporter of Classroom of Hope, a not-for- profit devoted to providing access to quality education and building schools in remote areas, which operates in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar. -

Honeybee Craig Silvey

AUSTRALIA OCTOBER 2020 Honeybee Craig Silvey The highly anticipated new novel by the bestselling author of Jasper Jones. Description 'Find out who you are, and live that life.' Late in the night, fourteen-year-old Sam Watson steps onto a quiet overpass, climbs over the rail and looks down at the road far below. At the other end of the same bridge, an old man, Vic, smokes his last cigarette. The two see each other across the void. A fateful connection is made, and an unlikely friendship blooms. Slowly, we learn what led Sam and Vic to the bridge that night. Bonded by their suffering, each privately commits to the impossible task of saving the other. Honeybee is a heart-breaking, life-affirming novel that throws us headlong into a world of petty thefts, extortion plots, botched bank robberies, daring dog rescues and one spectacular drag show. At the heart of Honeybee is Sam: a solitary, resilient young person battling to navigate the world as their true self; ensnared by a loyalty to a troubled mother, scarred by the volatility of a domineering step-father, and confounded by the kindness of new alliances. Honeybee is a tender, profoundly moving novel brimming with vivid characters and luminous words. It's about two lives forever changed by a chance encounter -- one offering hope, the other redemption. It's about when to persevere, and when to be merciful, as Sam learns when to let go, and when to hold on. About the Author Craig Silvey is an author and screenwriter from Fremantle, Western Australia.