Richard Wurmbrand Obtains Clothing for His

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tortured for Christ

Tortured for Christ PastorRichard Wurmbrand Dedication To the Rev. W. Stuart Harris, General Director of the European Christian Mission in London, who, upon my release from prison in 1964, came to Romania as a messenger from Christians in the West. Entering our house very late at night, after having taken many precautionary measures, he brought us words of love and comfort as well as relief for families of Christian martyrs. On behalf of these faithful believers, I hereby express our gratitude. Contents Foreword 1 The Russians' Avid Thirst for Christ 2 "Greater Love Hath No Man" 3 Ransom and Release for Work in the West 4 Defeating Communism With the Love of Christ 5 The Invincible, Widespread Underground Church 6 How Christianity Is Defeating Communism 7 How Western Christians Can Help Epilogue Foreword "The Martyr" Richard Wurmbrand said, "Tortured for Christ has no literary value. It was written in only three days shortly after my release from prison. But it was written with pen and tears. And for some reason, God has chosen to bless this writing and use it for His purpose." In this 30th anniversary edition of Tortured for Christ, little has been changed. The original testimony of a pastor's fourteen-year imprisonment under a Romanian dictatorship has been left intact. Over the years, Tortured for Christ has been translated into 65 languages and millions of copies have been distributed throughout the world. We are continually amazed at how this testimony has been used of God to strengthen His Body. We have discovered that in this Body, victory, courage, resilience, and tenacity know no borders, no skin color, no nationality, but are given equally to all by the Holy Spirit. -

Sabina Wurmbrand: Tortured for Christ

0ne g Sabina Wurmbrand: Tortured for Christ he guards in the hard-labor camp picked up Sabina Wurmbrand, held her by one T arm and one leg, and heaved her into the rocky canal the women in the prison camp had been working on. She thought she had broken a number of ribs, but since there was no medical care available in the prison, she could not be sure. She had been teaching Bible studies and praying with the women in her dormitory, so the guards wanted to make an example of her. They wanted to show the other women what would happen to them if they kept up their religious activities. Sabina Wurmbrand was imprisoned and tor- tured by the Communists in Romania for her faith in Jesus Christ in the 1950s before the fall of the Communist regime. She was the godly, devoted wife of Pastor Richard Wurmbrand and served with Beyond Suffering: Ten Women Who Overcame him in ministering to the underground church in Romania for years. While her husband was in prison, Sabina orga- nized the women and the few Christians left who were not in prison. She carried on ministry, just as she had worked beside her husband for so many years. The Communists told her that if she would renounce her faith, they would let him go. She re- fused. They then told her that if she would give them names of other Christians, they would set him free. Again, she refused. Richard Wurmbrand spoke warmly and openly about God’s faithfulness to him in prison when he stayed with us in Dallas, Texas, for a week. -

Is There a God? I Knew a Very, Very Poor Lady Who Had No Living Relatives

HELP FOR REFUGEES, INC. A tax-exempt, non-profit corporation Michael Wurmbrand, President Tel. (310) 544-0814, Fax: (310) 377-0511. PO Box 5161, Torrance, Ca. 90510, USA. Email: [email protected] ; Website: http://helpforrefugees.com May 2016 Genesis 1:1 “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. ” Late Reverend Richard Wurmbrand spent 14 years in Romanian communist prisons. Mrs. Wurmbrand was imprisoned nearly three years also for her Christian faith in same prisons. From an unpublished Bible meditation by late Reverend Richard Wurmbrand: Is there a God? I knew a very, very poor lady who had no living relatives. She boasted having lived all her life in a suburb. No one had ever invited her outside the neighborhood she lived in. Yet, same lady was very keen to get involved in any discussions about various political problems in this world. Since thousands of years there are controversies as to whether God exists and if He is, who is He, how He is and what should our relationship to Him be? None of us has seen the entire earthly globe, much less could we fathom this humongous universe. There is a spiritual universe as well that we hardly could contemplate. Wise Solomon wrote, "(God) has set eternity in the human heart." (Ecclesiastes 3:11) Any discussion of doubts about God just shows the common denominator of humanity: our boundless ignorance. Should we disbelieve His existence since our mind seems not to find him? It would be like doubting the existence of music because we cannot touch it. -

Resistance Through Literature in Romania (1945-1989)

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 11-2015 Resistance through literature in Romania (1945-1989) Olimpia I. Tudor Depaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Tudor, Olimpia I., "Resistance through literature in Romania (1945-1989)" (2015). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 199. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/199 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Resistance through Literature in Romania (1945-1989) A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts October, 2015 BY Olimpia I. Tudor Department of International Studies College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois Acknowledgements I am sincerely grateful to my thesis adviser, Dr. Shailja Sharma, PhD, for her endless patience and support during the development of this research. I wish to thank her for kindness and generosity in sharing her immense knowledge with me. Without her unconditional support, this thesis would not have been completed. Besides my adviser, I would like to extend my gratitude to Dr. Nila Ginger Hofman, PhD, and Professor Ted Anton who kindly agreed to be part of this project, encouraged and offered me different perspectives that helped me find my own way. -

Christ in the Communist Prisons Also by REVEREND RICHARD WURMBRAND

Christ in the Communist Prisons Also by REVEREND RICHARD WURMBRAND CHRIST ON THE JEWISH ROAD today's martyr church tortured for CHRIST WURMBRAND's LETTERS CHRIST IN THE COMMUNIST PRISONS Reverend Richard Wurmhrand Edited hj Charles Foley COWARD-McCANN, INC. New York This hook is dedicated to the memory of those who died for God and fatherland in Communist prisons First American Edition 1968 Copyright (g) 1968 by Richard Wurmbrand All rights reserved. This hook, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the Publisher, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 68-11879 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Christ in the Communist Prisons Chapter One T« first half of my life ended on February 29, 1948. I was walking from our home to my church nearby when a black Ford braked sharply beside me and two men jumped out, seized my arms and shoved me into the back seat, while a third, beside the driver, kept me covered with an automatic. The car sped through the cold, gray streets of Bucharest and turned in through steel gates in Calea Rahova street. My kidnappers belonged to the Communist Secret Police and this was their headquarters. Inside, my papers, my belong ings, my tie and shoelaces, and finally my name were taken from me. "From now on," said the official on duty, "you are Vasile Georgescu." It was a common name, easy to forget. The authorities did not want even the guards to know the identity of their pris oner, in case the secret should leak out and questions be asked abroad, where I was well-known. -

537E34d0223af4.56648604.Pdf

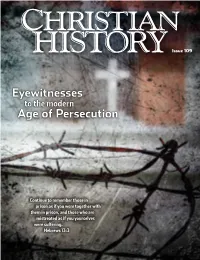

CHRISTIAN HISTORY Issue 109 Eyewitnesses to the modern Age of Persecution Continue to remember those in prison as if you were together with them in prison, and those who are mistreated as if you yourselves were suffering. Hebrews 13:3 RARY B I L RT A AN M HE BRIDGE T COTLAND / S RARY, B I L RARY B NIVERSITY I U L RT A AN LASGOW M G “I hAD TO ASK FOR GRACe” Above: Festo Kivengere challenged Idi Amin’s killing of Ugandan HE BRIDGE Christians. T BOETHIUS BEHIND BARS Left: The 6th-c. Christian ATALLAH / M I scholar was jailed, then executed, by King Theodoric, N . CHOOL (14TH CENTURY) / © G an Arian. S RARY / B TALIAN I I L ), Did you know? But soon she went into early labor. As she groaned M in pain, servants asked how she would endure mar- CHRISTIANS HAVE SUFFERED FOR tyrdom if she could hardly bear the pain of childbirth. , 1385 (VELLU She answered, “Now it is I who suffer. Then there will GOSTINI PICTURE A THEIR FAITH THROUGHOUT HISTORY. E be another in me, who will suffer for me, because I am D HERE ARE SOME OF THEIR STORIES. also about to suffer for him.” An unnamed Christian UM COMMENTO woman took in her newborn daughter. Felicitas and C SERVING CHRIST UNTIL THE END her companions were martyred together in the arena Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, is one of the earliest mar- in March 202. TALY, 16TH CENTURY / I tyrs about whom we have an eyewitness account. In HILOSOPHIAE P E, M the second century, his church in Smyrna fell under IMPRISONED FOR ORTHODOXY O great persecution. -

Late Reverend Richard Wurmbrand Biography

LATE REVEREND RICHARD WURMBRAND BIOGRAPHY Richard Wurmbrand, author of 18 worldwide Christian bestsellers, translated in over 80 languages some describing his 14 years of communist imprisonment, was born in 1909, the youngest of four boys, in a Jewish family in Bucharest, Romania. Shortly thereafter, the father, a dentist established a practice and moved the family to Istanbul, Turkey. Upon the death of the father from a flu epidemic in 1919, the now extremely poor family returned to Romania. Richard, intellectually gifted, fluent in 9 languages, had a stormy youth, was active in leftist politics and working as a stockbroker when marrying Sabina in 1936. Same year, the Jewish couple met during a vacation in the Romanian mountains, a German carpenter who placed a Bible into their hands. Hardly having any education and unable to answer their questions, this carpenter did not do much more than urge these two young, educated, Jewish intellectuals to just take the time and read at least one of the Gospels, in essence a short biography of the most famous personality of the Jewish people, Jesus Christ. Sabina and Richard meeting also other Jewish-Christians converted and were baptized. They joined the church of the Anglican Mission to the Jews in Bucharest, Romania. Eventually studying on his own, Richard a charismatic speaker, was first ordained as an Anglican and then after WW II re-ordained as a Lutheran minister. Their only son, Michael was born in 1939. Due to Romania's declaration of war against England and the other Western Powers, at the beginning of WWII, the foreign Anglican minister had to leave Romania. -

Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. 16-1274 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States __________ TING XUE, Petitioner, v. JEFFERSON B. SESSIONS III, Respondent. __________ On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit __________ BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE FOUNDATION FOR MORAL LAW AND THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF EVANGELICAL CHAPLAIN ENDORSERS IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER __________ ARTHUR A. SCHULCZ, SR. JOHN EIDSMOE CHAPLAINS’ COUNSEL, PLLC Counsel of Record 21043 Honeycreeper Place FOUNDATION FOR Leesburg VA 20175 MORAL LAW (703) 645-4010 One Dexter Avenue [email protected] Montgomery AL 36104 (334) 262-1245 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................... ii INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ............................. 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 2 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................... 3 ARGUMENT ................................................................ 5 I. The Court should grant certiorari because the split in the circuits creates uncertainty and disruption in the immigration, naturalization, and asylum process. .................................................... 5 II. The Tenth Circuit erred by considering issues of persecution narrowly rather than looking to the broader policies of the Government of China and its ruling Communist Party. ............................................... 6 III. The Tenth Circuit erred by failing to consider the effect of the Religious -

Richard Wurmbrand If That Were Christ, Would You Give Him Your Blanket?

Richard Wurmbrand If that were Christ, would you give him your blanket? Tortured for Christ. // That Were Christ Would You Give Him Your Blanket? Two Qiinese Christians shivered with cold in a cell. Each had a thin blanket. One of the Christians looked to the other and saw how he trembled. The thought came to him, 'If that were Christ, would you give Him your blanket?' Of course he would. Immediately he spread the blanket over his brother. By the same author TORTURED FOR CHRIST IN GOD'S UNDERGROUND THE SOVIET SAINTS SERMONS IN SOLITARY CONFINEMENT If That Were Christ Would You Give Him Your Blanket? by Richard Wurmbrand HODDER AND STOUGHTON London Sydney Auckland Toronto Copyright © 1970 by Richard Wurmbrand First printed 1970 ISBN o 340 12534 9 All rights reserved No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical including photocopy recording or any information storage and retrieval system without permis- sion in writing from the publisher Printed in Great Britain for Hodder and Stoughton Limited St. Paul's House Warwick Lane London E.C4 by Hazell Watson & Viney Ltd Aylesbury Bucks Contents Chapter Page I Episodes in the Life of the Underground Church 7 2 Does the Underground Church Exist? 25 3 Facts, Only Documented Facts 33 4 Russia's Golgotha 39 5 How Many Christians are Jailed in the Soviet Union? 47 6 The Prison Regime *52 7 Red China 55 8 The Christian Church at Midnight 6i 9 Romania : a Liberal Communist Country 65 IO The Absolute Torture 69 ii Beauty Shines at Midnight 79 12 Persecutions of Christians in Africa 83 13 The Attitude of the Church of the Free World Towards Communism 87 What We Should Not Do 94 15 What Can Be Done? 98 i6 The Need for Literature 103 17 Broadcasting the Gospel 106 i8 Help to Underground Pastors and Families of Christian Martyrs 108 19 Answer to the Most Frequent Criticisms 112 20 My Last Word 122 'There is no better rest in this restless world than to face imminent peril of death solely for the love and service of God our Lord.' St. -

Read an Interview Given on 7/2/2016 Describing the Suffering of Michael

Our marathon continues. It is the 4th of July, the day that Americans celebrate their national day. It is also the national day of Romanians who are in the States. Someone once said that Romanians have two national days - December 1st and July 4th. It was a real joy for us to meet so many Romanians who live all over America and I would like to thank them again for the effort they made to come to our small TV studio - Nasul TV USA, based in Detroit. I am here with a gentleman who came from far away, from Los Angeles, Mr Mihai Wurmbrand. Welcome to Nasul TV USA. MW: I am honored by your invitation. Thank you! Thank you. I am so glad we got to meet. People know a lot of things about your father and about you as well. A lot of friends told me before I came here, "You can talk with this guy about everything, on every subject" and that's why I would like us to talk less about your father, about whom maybe thousands of shows have been made, who preached tens of thousands of sermons. He is well known around the world, his books were translated into. I don't even know how many languages. MW: 85 languages. 85 languages. So he is considered one of the greatest Christian writers of the world. He lived a long time, he served 14 years in prison and when he got out he declared his love towards all his persecutors. He was incapable of hatred. -

A Lost Voice for the Martyrs

NEWS COMINAD Unveils Adopt-A- Bible League and Adopt-a-People Village Project Clearinghouse Merge ORLANDO Reconciliation Ministries Aiming to enhance the unreached people groups with Over 50 members of the Network, Carver International goals of both ministries, The resources for “adopting” them Cooperative Missions Network Missions, South Africa Inland Bible League and the Adopt- through prayer, partnership, of the African Dispersion Missions, National Black A-People Clearinghouse have provision and personnel. (COMINAD) met on April 9- Evangelical Association and announced plans for a merger 12, 2001 at Wycliffe’s Bible Campus Crusade. They were to be completed by early 2002. Translators’ Center for a asked to take part in a “nuts “This merger will greatly Up and Coming conference that challenged all and bolts” type meeting to increase discipleship training COMING TOGETHER attendees to participate in the plot a workable way to make around the world by enabling FOR UNITY development process of the the vision reality. a greater number of un- In what has been de- Adopt-A-Village (AAV) “I feel like I got a peek reached people groups to be scribed as the most compre- project. Envisioned by Brian into a Kingdom Construction introduced to the Word,” said hensive meeting of mission Johnson, COMINAD’s planning meeting around the Dennis Mulder, President of workers in over 40 years, a national coordinator, AAV is all throne,” said one participant. The Bible League. broad spectrum of mission about “building relationships Some challenging issues that The Bible League was associations will join with between villages in Africa and were covered during this founded in 1938 and to make relief and development asso- the churches in the West, for development phase included Scripture available through ciations and others for a the purpose of furthering God’s coordinating a networking training and supplying local convention entitled Kingdom,” Johnson said. -

And I Saw Another Angel Ascending from the East, Having the Seal of the Living God" (Revelation 7:2)

HELP FOR REFUGEES, INC. A tax-exempt, non-profit corporation Michael Wurmbrand, President Tel. (310) 544-0814, Fax: (310) 377-0511. PO Box 5161, Torrance, Ca. 90510, USA. Email: [email protected]; Website: http://helpforrefugees.com March 2019 “And I saw another angel ascending from the east, having the seal of the living God" (Revelation 7:2) Late Reverend Richard Wurmbrand spent 14 years in Romanian communist prisons. Mrs. Wurmbrand was imprisoned for nearly three years, also for her Christian faith in some of the same prisons. From an unpublished Bible meditation by late Reverend Richard Wurmbrand The Seal of the Living God The seal that the world puts on the foreheads of its elect is success and popularity. These should be of no great value to the children of God. INFILTRATION IN THE CHURCH When arriving to the West from communist Romania, I warned that Communism would expand to new countries. It is "the red dragon" (Revelation 12:3) ready to devour the church. It will never be satiated until it has the whole world under its heel. This same demonic spirit works in all countries that fell under communist rule. In Cuba for instance, CASTRO attended the execution of a Christian by firing squad. As his hands were tied behind his back, CASTRO told him, "Kneel and beg for your life." The Christian shouted back, "I kneel for no man." A sharpshooter put first one bullet through one knee, then through the other. CASTRO exulted, "You see, we made you kneel." The man was finished slowly by putting bullets through the non-vital parts of the body, prolonging the agony." (JOHN MARTINO, "I was CASTRO's Prisoner.") The devil himself works through these anti-Christian dictators.