Engaging the Power of the Theatrical Event by William Weigler B.A., Oberlin College, 1982 a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SATURDAY 11TH AUGUST 06:00 Breakfast 10:00

SATURDAY 11TH AUGUST All programme timings UK All programme timings UK All programme timings UK 06:00 Breakfast 09:25 James Martin's Saturday Morning 09:50 The Big Bang Theory 06:00 The Forces 500 Back-to-back Music! 10:00 Saturday Kitchen Live 11:20 James Martin's American Adventure 10:15 The Cars That Made Britain Great 07:00 The Forces 500 Back-to-back Music! 11:30 Food & Drink 11:50 Eat, Shop, Save 11:05 Carnage 08:00 I Dream of Jeannie 12:00 Football Focus 12:20 Love Your Garden 11:55 Brooklyn Nine-Nine 08:30 I Dream of Jeannie 13:00 BBC News 13:20 10K Holiday Home 12:20 Sanctuary 09:00 I Dream of Jeannie 13:15 European Championships~ 13:50 ITV Lunchtime News 13:05 Shortlist 09:30 I Dream of Jeannie 14:00 Tenable 13:10 Modern Family 10:00 I Dream of Jeannie 15:00 Tipping Point: Lucky Stars 13:35 Modern Family 10:30 Hogan's Heroes 16:00 The Chase 14:00 Malcolm in the Middle 11:00 Hogan's Heroes 17:00 WOS Wrestling 14:25 Malcolm in the Middle 11:30 Hogan's Heroes 18:00 ITV Evening News 14:50 Ashley Banjo's Secret Street Crew 12:00 Hogan's Heroes 18:15 ITV News London 15:40 Jamie and Jimmy's Friday Night Feast 12:35 Hogan's Heroes 18:30 Japandemonium 16:35 Bang on Budget 13:00 Airwolf 19:00 Big Star's Little Star 17:30 Forces News Reloaded 14:00 The Phil Silvers Show Stephen Mulhern hosts the fun entertainment 17:55 Shortlist 14:35 The Phil Silvers Show show. -

Putting Together a Powerful Password

B10 THE NEWS-ENTERPRISE CLASSIFIEDS TUESDAY, MARCH 20, 2012 CROSSWORD Putting together a powerful password Dear Readers: Computer by the rental-car company mail, newspapers, advertis- passwords are necessary was, “We can’t do that, be- ing fliers and packages. If and an important part of on- HINTS cause people take them.” you’re going to be gone for line security. What’s not a FROM At least they should pho- a long time, stop mail via good password? According HELOISE tocopy pages out of the www.usps.com under “Man- to the Federal Trade Com- handbook addressing the age Your Mail.” Call your mission, things that are easi- important issues (e.g., wind- newspaper to stop it as well. ly associated with you are binder with dividers in it. I shield wipers, lights, radio, ■ The lawn needs to be not good passwords: your label the dividers so I can portable media players, jack maintained. pets’ names, your birthday, keep my hints separate from placement for flat tires, haz- ■ Park a car in the drive- your mother’s maiden name articles. It really helps to ard buttons, etc.). — Linda in way so it looks like some- or any part of your phone keep my house and office Colorado Springs, Colo. one is home. number. Also, consecutive much cleaner. — Barbara in ■ Heloise Central called ■ Turn down the ringer numbers, simple words and Antelope, Calif. several rental-car agencies, on your phone. A phone is the word “password” are MISSING OWNERS MANUAL. and I’ll be darned, for the a clue no one is home. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

BROADWAY BOUND: Mezer's Modest Proposals This Piece Comes to You Compliments of ACREL Fellow Steve Mezer of Becker & Poli

BROADWAY BOUND: Mezer’s Modest Proposals This piece comes to you compliments of ACREL Fellow Steve Mezer of Becker & Poliakoff who has a front row view of Broadway for several reasons. He is on the Board of the Straz Performing Arts Center in Tampa that invests in and presents Broadway shows. He is also a theater aficionado who spends his free time in NYC with his wife Karen bingeing on Broadway and Off Broadway musicals. Broadway theater is a unique American cultural experience. Other cities have vibrant theater scenes, but no other American venue offers Broadway’s range of options. I recommend that you come a day early and stay a date later for our Fall meeting in New York and take in a couple of Broadway shows. I grew up 90 miles outside of New York City; Broadway was and remains a family staple. I can neither sing nor dance, but I have a great appreciation for musical theater. So here are my recommendations: Musicals: 2016 was one of Broadway’s most successful years as it presented many original works and attracted unprecedented attention with Hamilton and its record breaking (secondary market) ticket prices. October is a transition month, an exciting time to see a new Broadway show. Holiday Inn, an Irving Berlin musical, begins previews September 1, and opens on October 6 at Studio 54. Jim (played by Bryce Pinkham) leaves his farm in Connecticut and meets Linda (Laura Lee Gayer) a school teacher brimming with talent. Together they turn a farmhouse into an inn with dazzling performances to celebrate each holiday. -

GLOCK Sport Shooting Foundation Inside the Gunny Challenge: a History

www.GSSFonline.com Volume II, 2012 The newsletter of the GLOCK Sport Shooting Foundation Inside The Gunny Challenge: A History. The Gunny Challenge: The GLOCK Sport Shooting Foundation began in 1991. The goal was to in- A History Pgs 1-3 troduce new GLOCK shooters to sport shooting and the use of stock GLOCK firearms. Benefits of GSSF Member- ship & FAQ Pgs 4-5 As with any sport, some Welcome to GSSF / GSSF competitors will excel. How- Rules Pgs 6-27 ever, if a few skilled shoot- ers are allowed to garner all Gunny Challenge VIII Charity of the prizes, it can discour- Donation Pg 29 age others from participat- Course of Fire: Five to ing. In order to prevent this, GLOCK Pgs 31-33 GSSF divides participants into two shooting classes. Course of Fire: GLOCK’M Pgs 34-38 Special Pullout Section: An Amateur is any GSSF participant who has not achieved Master status. Mas- 2013 GSSF Match Schedule ter class participants are those shooters who rank Master or above in other Pgs 39-42 shooting disciplines or have won three performance firearms awards at GSSF matches. As Master shooters, they mostly compete against other Master classed Course of Fire: GLOCK the Plates Pgs 43-44 competitors and do not take awards out of the reach of Amateur GSSF competi- tors. The only divisions in which Amateur and Master shooters compete for the GSSF Armorer’s Service same prizes are Master Stock and Master Unlimited. Pg 45 In 2000, GSSF instituted the Matchmeister title for the best single score across all The “New River GLOCK” Pg 46 comparable stock divisions within a given match. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Greetings From

OPERATION FOOTLOCKER THE NATIONAL WWII MUSEUM GREETINGS FROM and welcome to the exciting, hands-on world of WWII artifacts. We are pleased that you and your students will be discovering the history and lessons of WWII by exploring the artifacts in this footlocker. As a classroom teacher, you represent the front line of teaching WWII history to your students. We hope that by using this footlocker of WWII artifacts, your students will gain a richer appreciation for WWII history and for history in general. Please take a moment to review the instructions in this binder before going any further. Following these directions will ensure that your students get the most out of these artifacts and that the artifacts are properly handled and preserved for students in the future. 1 OPERATION FOOTLOCKER THE NATIONAL WWII MUSEUM Directions for returning footlocker Your footlocker must be shipped back to the Museum on or before the date on your Reservation Form. When ready to return, please: 1. Please complete our on-line Evaluation Form . http://support.nationalww2museum.org/site/Survey?ACTION_REQUIRED=URI_AC TION_USER_REQUESTS&SURVEY_ID=1440 2. Fill out the Artifact Inventory and Condition Report and place it in the pocket of the Teacher Manual. Do not hesitate to let us know about any breakage that occurred during your sessions. That way we can replace or repair them before we send the footlocker to another school. 3. Inspect the original cardboard packing box and wooden Footlocker. Both should be able to safely withstand cross-country shipment. Call us if there is an issue at 504-528-1944 x 333. -

Uvisno "Acting Is Handed on from Actor to Actor

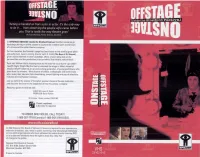

Inaide the Stratford Festival uviSNO "Acting is handed on from actor to actor. It's the only way to do it... from observing the people who came before you. That is really the way theatre goes" In OFFSTAGE ONSTAGE: Inside the Stratford Festival, Stratford cameras go backstage during an entire season to capture the creative spirit at the heart of a treasured Canadian theatre company. For five decades, the Festival's stage has been home to the world's great plays and performers. Award-winning director John N. Smith (The Boys of St. Vincent), given unprecedented access backstage, offers a fascinating look at the personalities and the production process behind live theatre performance. Peek into William Hutt's dressing room as he does his vocal warm-ups before Twelfth Night. Watch Martha Henry command the stage in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Observe an up-and-coming generation of young performers who learn from the masters. Meet dozens of artists, craftspeople and technicians who reveal their secrets, from shoemaking, sword fighting and sound effects to makeup and mechanical monkeys. Join us behind the scenes of Canada's premier classical theatre institution ... and discover the love for the stage that drives this artistic company. Resource guide on reverse side, DIRECTOR: John N. Smith PRODUCER: Gerry Flahive 83 minutes Order number: C9102 042 Closed captioned. A decoder is required. TO ORDER NFB VIDEOS, CALL TODAY! -800-267-7710 (Canada) 1-800-542-2164 (USA) © 2002 National Film Board of Canada. A licence is required for any reproduction, television broadcast, sale, rental or public screening. -

The Upstart Crow, Volume XXIX

Clemson University TigerPrints Upstart Crow (Table of Contents) Clemson University Press Fall 2010 The Upstart Crow, Volume XXIX Elizabeth Rivlin, Editor Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/upstart_crow Recommended Citation Rivlin, Editor, Elizabeth, "The Upstart Crow, Volume XXIX" (2010). Upstart Crow (Table of Contents). 30. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/upstart_crow/30 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Clemson University Press at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Upstart Crow (Table of Contents) by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol_XXIX Clemson University Digital Press Digital Facsimile Vol_XXIX Shakesp ear ean Hearing guest edited by Leslie Dunn and Wes Folkerth Contents Essays Leslie Dunn and Wes Folkerth Editors’ Introduction to “Shakespearean Hearing” ....5 Erin Minear “A Verse to this Note”: Shakespeare’s Haunted Songs .................... 11 Kurt Schreyer “Here’s a knocking indeed!” Macbeth and the Harrowing of Hell ... 26 Paula Berggren Shakespeare and the Numbering Clock ..........................................44 Allison Kay Deutermann “Dining on Two Dishes”: Shakespeare, Adaptation, and Auditory Reception of Purcell’s Th e Fairy-Queen ..................................... 57 Michael Witmore Shakespeare’s Inner Music ................................................. 72 Performance Reviews Michael W. Shurgot and Peter J. Smith Th e 2010 Season at London’s Globe Th eatre .........................................................................................................83 Sara Th ompson Th e Royal Shakespeare Company 2009:As You Like It ............. 99 Owen E. Brady Th e 2009 Stratford Festival:Macbeth and Bartholomew Fair ..103 Michael W. Shurgot Th e 2009 Oregon Shakespeare Festival ..............................111 Bryan Adams Hampton Th e 2010 Alabama Shakespeare Festival:Hamlet ..... -

The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521651239 - The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter provides an introduction to one of the world’s leading and most controversial writers, whose output in many genres and roles continues to grow. Harold Pinter has written for the theatre, radio, television and screen, in addition to being a highly successful director and actor. This volume examines the wide range of Pinter’s work (including his recent play Celebration). The first section of essays places his writing within the critical and theatrical context of his time, and its reception worldwide. The Companion moves on to explore issues of performance, with essays by practi- tioners and writers. The third section addresses wider themes, including Pinter as celebrity, the playwright and his critics, and the political dimensions of his work. The volume offers photographs from key productions, a chronology and bibliography. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521651239 - The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO LITERATURE The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy The Cambridge Companion to the French edited by P. E. Easterling Novel: from 1800 to the Present The Cambridge Companion to Old English edited by Timothy Unwin Literature The Cambridge Companion to Modernism edited by Malcolm Godden and Michael edited by Michael Levenson Lapidge The Cambridge Companion to Australian The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Literature Romance edited by Elizabeth Webby edited by Roberta L. Kreuger The Cambridge Companion to American The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women Playwrights English Theatre edited by Brenda Murphy edited by Richard Beadle The Cambridge Companion to Modern British The Cambridge Companion to English Women Playwrights Renaissance Drama edited by Elaine Aston and Janelle Reinelt edited by A. -

Wing Unit Praised for Safety Join the Marine Forces Pacific Big Band at a Free Concert at the Hale Let Marines Know What and Where Koa Hotel Wednesday at 10 Am, Sgt

INSIDE GOOD HOLIDAY Attack A-8 Registration A-9 Buys, B-1 Season, B-1 Ticket to Fun B-2 C Vol. 26, No. 47 Serving the base of choice for the 21st century December 4, 1997 Band Concert Wing unit praised for safety Join the Marine Forces Pacific Big Band at a free concert at the Hale let Marines know what and where Koa Hotel Wednesday at 10 am, Sgt. Michael Wiener the hazards are," O'Connor said. The band will be playing jazz rendi- Combat Correspondent prq "When the Marines are aware of cer- tions of Christmas music. For more Marine " Heavy Helicopter tain hazards, they'll be more safety all the lflatities gitfalk7,1'; information, call 257-7350.. Squadron 463 received the Chief of conscious in performing their jobs." Naval Operations Award, Nov. 24. iTCoL. CiiRISTOPtiER ONINO With award in hand, the squadron The CNO award is given to Marine has no intention of slowing down. Musical Celebration k_oirrita/14/tri,1; r)f Corps and Navy squadrons for avia- "Our focus is to have zero tion safety excellence. mishaps," O'Connor said. "This hap- A musical celebration of Christmas "When the CNO decides who to pens through the hard work and will be held at the Base Chapel give the award to, he takes into con- "The award is an achievement of ism and hard work of all the professional approach our Marines Sunday at 6:30 p.m. This service is sideration deployments, flight an outstanding safety record, both in Marines in the squadron." have while carrying out day-to-day open to everyone and will feature hours, deck landings and other aviation and on the ground," said The squadron's success to because operations." music from the past, including things," said Maj. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter.