Targeting Female Arts Audiences Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

~La6(8Ill COMPA.NIES INC

October 1999 Brooklyn Academy of Music 1999 Next Wave Festival BAMcinematek Brooklyn Philharmonic 651 ARTS ~' pi I'" T if II' II i fl ,- ,.. til 1 ~ - - . I I I' " . ,I •[, II' , 1 , i 1'1 1/ I I; , ~II m Jennifer Bartleli, House: Large Grid, 1998 BAM Next Wave Festival sponsored by PHILIP MORRIS ~lA6(8Ill COMPA.NIES INC. Brooklyn Academy of Music Bruce C. Ratner Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins Joseph V. Melillo President Executive Prod ucer presents Moby Dick Running time: BAM Opera House approximately ninety October 5, 1999, at 7:00 p.m. (Next Wave Festival Gala) minutes. Songs and October 6-9 & 12-16, 1999, at 7:30 p.m. Stories from Moby Dick is performed without an Visual Design, Music, and Lyrics Laurie Anderson intermission. Performers Pip, The Whale, A Reader Laurie Anderson Ahab, Noah, Explorer Tom Nelis The Cook, Second Mate, Running Man Price Waldman Standing Man Anthony Turner Falling Man Miles Green Musicians Violin, keyboards, guitar, talking stick Laurie Anderson Bass, prepared bass, samples Skuli Sverrisson Artistic Collaborators Co-Visual Design Christopher Kondek Co-Set Design James Schuette Lighting Design Michael Chybowski Sound Design Miles Green Costume Design Susan Hilferty Electronics Design Bob Bielecki Video Systems Design Ben Rubin Staging Co-Direction Anne Bogart General Management Julie Crosby Production Management Bohdan Bushell Production Stage Management Lisa Porter Major support for this presentation was provided by The Ford Foundation with additional support from The Dime Savings Bank of New York, FSB. Next Wave Festival Gala is sponsored by Philip Morris Companies Inc. 17 Produced by electronic theater company, Inc. -

P P P P P N E

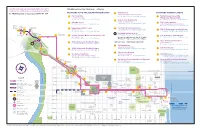

ind PHLASH on-the-go Use RidePhillyPHLASH.com to PHLASH service runs 10:00 a.m. – 6:00 p.m. track the next vehicle to arrive at your stop in real time. WESTOUND TO THE PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM O ART Rodin Museum EASTOUND TO PENNS LANDIN or PHLASH customer service please call 484-881-3574. 8 22nd St & Benjamin Franklin Parkway 1 Penns Landing First pickup 1015 a.m., last pickup 545 p.m. 15 Rocky Statue & Steps of the Chestnut St Overpass Philadelphia Museum of Art First pickup 1000 a.m., last pickup 530 p.m. 9 Eastern State Penitentiary First pickup 1025 a.m., last pickup 555 p.m. 3rd & Market Sts 22nd St & Fairmount Ave The ranklin Institute 2 First pickup 1017 a.m., last pickup 547 p.m. 16 First pickup 1003 a.m., last pickup 533 p.m. 20th St & Benjamin Franklin Parkway Shofuso First pickup 1027 a.m., last pickup 557 p.m. apanese Please House Touch Museum Fairmount Park, and arden Boathouse Row 3 Independence Visitor Center 10 airmount & Pennsylvania Aves 12 First pickup 101 a.m., last pickup 54 p.m. 17 18th St & enamin ranklin Parkway 13 6th & Market Sts First pickup 1005 a.m., last pickup 535 p.m. First pickup 102 a.m., last pickup 55 p.m. 14 Phila Museum Philadelphia Museum of Art of Art Eastern State 11 Philadelphia Perelman ldg 9 Penitentiary Reading Terminal Market & Convention Center First pick up 1022 a.m., last pickup 552 p.m. Zoo 4 18 17th St & ohn . ennedy lvd 10 12th & Market Sts Use transfer vehicle here for stops 12 13 and 14. -

Guide to Philadelphia

GUIDE TO PHILADELPHIA EAT POP-UPS FOR TASTY BITES EXPLORE THE CITY OF PUBLIC ART 3728 Windy Bush Road New Hope, PA 18938 PLAY PHILLY FOR -iÌ>Li>ÕÌvÕÇ°x>VÀiÃÌÃÌÃ>>}wViÌÀiV ÃÌÞiiÃÌ>Ìi°/ à ivi>ÌÕÀiÃ>«i OLD SOULS yiÝLiyÀ«>vi>ÌÕÀ}>>ÃÌiÀV iv½ÃÌV i]>ÌÜÃÌÀÞVÌ>}>}>ÃÃ`}À]>wÀÃÌ & BEACH BUMS yÀ>ÃÌiÀÃÕÌi]>ë>VÕÃ}Ài>ÌÀÜÌ > }à *ÕLÉLÕÌL>À]>{³V>À}>À>}iV«iÝ] >`ÃÕV Àit ÛiÀÞÕÝÕÀÞ>`VvÀÌ>ÃLiiVÃ`iÀi`vÀÌ`>Þ½Ã`iÀÛ}°/ à LÀi>Ì Ì>}v>ÞV«Õ`vviÀëÀÛ>VÞ]µÕ>ÌÞ>`ÕÝÕÀÞ>`i>ÃiÌÌ}° ÝVÕÃÛiÞÃÌi`>ÌfÓ]{]äää CARYN BLACK Ƃ-" ,Ƃ6/< ÓÈÇ°È£{°È{n{ ÓÈÇ°ÎÓ{°{£{£ JULY 2018 >ÀÞ >VJÕÀvÃðV [email protected] ÜÜÜ° >ÀÞ >V°V www.RealtorJK.com wheretraveler.com ÕÀvÃÃ-Ì iLÞ½ÃÌiÀ>Ì>,i>ÌÞN£ÈΣVÕÃÌ-ÌÀiiÌ-ÕÌiÎää* >`i« >]*Ƃ££äÎN >V "vvViÃ`i«i`iÌÞÜi`E«iÀ>Ìi` Philadelphia 07.18 CONTENTS SEE MORE OF PHILADELPHIA AT WHERETRAVELER.COM the plan the guide 02 Editor’s Itinerary 10 SHOPPING The essential things to see XX and do in Philadelphia, plus Top spots to shop, from a 90-minute visit to a family- department stores to friendly riverside attraction. independent boutiques 04 Where Calendar 17 GALLERIES & Hot Dates This Month XX ANTIQUES Top things to do in July. Paintings, photography, “Covenant” (1974) sculptures, antiques, plus 9 Alexander Liberman exhibitions to see now 21 DINING XX Morgan’s Pier Beer Garden Tasty Philly restaurants, from fine dining to fast casual, in more than a dozen neighborhoods XX 28 ENTERTAINMENT 40 Philadelphia Your Way Fun bars, hip lounges, world- Our picks for seeing the city class theater and many more with the gals, old souls, beach ways to enjoy the arts lovers—or all three. -

Ffy 2019-2022 Executive Summary August 16, 2018

The D&L Trail Mansion House Bridge over Lehigh River in Jim Thorpe, Carbon County Photo by Ronald J. Young, Jr., M.P.A. PENNSYLVANIA’S STATEWIDE TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM FFY 2019-2022 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AUGUST 16, 2018 CONTENTS Section Page OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT GUIDANCE: Financial Guidance .......................................................................................................................... 3 General and Procedural Guidance .................................................................................................. 3 STATE TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM: Highway and Bridge Summary ........................................................................................................ 5 Transit Summary ............................................................................................................................. 8 Statewide Programs ..................................................................................................................... 11 TRANSPORTATION PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT ................................................................................................ 14 MANAGING STIP FUNDING .............................................................................................................................. 31 AIR QUALITY ................................................................................................................................................ -

Saturday-Night-Fever.Pdf

® PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA PLAYBILL.COM PLAYBILLVAULT.PLAYBILL.COMCOM PLAYBILLVAULT.COM 06-01 SatNightFever2_Live.indd 1 5/12/17 3:22 PM Dear Theatregoer, Welcome to Saturday Night Fever! I am so glad to have you as our guest for this incredible season finale. The energy this cast brings to the stage will make you want to get up and dance to the iconic music from the legendary Bee Gees. I’m thrilled to share this electrifying production with you. Next season the excitement continues on our Mainstage with a spectacular line-up. The 2017–18 season will begin with Broadway’s classic Tony Award-winning Best Musical A Funny Thing Happened On the Way to the Forum. You’ll meet Pseudolus, a crafty slave who struggles to win the hand of a beautiful, but slow-witted, courtesan for his young master. The plot twists and turns with cases of mistaken identity, slamming doors and a bevy of beautiful showgirls. I think this musical comedy is one of the funniest Broadway shows ever written, and I’m sure you’ll agree. During the holiday season we’ll look to a brighter “tomorrow” with one of the world’s best-loved musicals Annie. This Tony Award- winning Best Musical features some of the greatest musical theatre Photo: Mark Garvin hits ever written including “It’s the Hard Knock Life,” “Easy Street,” and “Tomorrow.” I’m excited to share this exciting production with you and your family, as Annie fills our hearts with joy! Our season continues with The Humans. This comedy won more than 20 Best Play awards in 2016, including the Tony Award. -

The Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia 4-RC-21019 6-9-05

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BEFORE THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD REGION FOUR CONCERTO SOLOISTS d/b/a THE CHAMBER ORCHESTRA OF PHILADELPHIA1 Employer and Case 4–RC–21019 PHILADELPHIA MUSICIANS’ UNION LOCAL 77, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF MUSICIANS, AFL-CIO2 Petitioner REGIONAL DIRECTOR’S DECISION AND DIRECTION OF ELECTION The Employer, The Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia, is a small, elite orchestra which performs at concerts and other engagements. The Petitioner, Philadelphia Musicians’ Union Local 77, has filed a petition with the National Labor Relations Board under Section 9(c) of the National Labor Relations Act seeking to represent a unit of the Musicians who perform in the Chamber Orchestra. There are about 33 Musicians in the petitioned-for unit. The Employer contends that the Musicians are independent contractors and thus are excluded from the coverage of the Act. A hearing officer of the Board held a hearing, and the parties filed briefs. I have considered the evidence and the arguments presented by the parties, and as discussed below, I have concluded that the Musicians are statutory employees. Accordingly, I am directing an election in a bargaining unit of the Employer’s Musicians.3 To provide a context for my discussion, I will first present a brief overview of the Employer’s operations. Then, I will review the factors that must be evaluated in determining independent contractor status and present in detail the facts and reasoning that support my conclusion that the Musicians are statutory employees. 1 The Employer’s name was amended at the hearing. 2 The Petitioner’s name was amended at the hearing. -

Progress 2009 Annual Report

SPARKING PROGRESS 2009 ANNUAL REPORT Southeastern SEPTAPennsylvania Transportation Authority Board Members Chairman Vice Chairman Pasquale T. Deon, Sr. James C. Schwartzman, Esquire SEPTA Board SEPTA Officers Philadelphia Governor Appointee General Manager Beverly Coleman Denise J. Smyler, Esquire Joseph M. Casey, CPA Rina Cutler Senate Majority Leader Chief Financial Officer/ Bucks County Appointee Treasurer Pasquale T. Deon, Sr. Honorable Stewart J. Greenleaf, Richard G. Burnfield Honorable Charles H. Martin Esquire General Counsel Chester County Senate Minority Leader Nicholas J. Staffieri, Esquire Joseph E. Brion, Esquire Appointee Kevin L. Johnson, P.E. James C. Schwartzman, Esquire Controller to the Board Stephen A. Jobs, CPA Delaware County House Majority Leader Thomas E. Babcock Appointee Secretary to the Board Daniel J. Kubik Frank G. McCartney Elizabeth M. Grant Montgomery County House Minority Leader Thomas Jay Ellis, Esquire Appointee Michael J. O’Donoghue, Esquire Herman M. Wooden Created by the State Legislature in 1964, the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority was formed to plan, develop and coordinate a regional transportation system for Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Montgomery and Philadelphia counties. It has the right to acquire, construct, operate, lease and otherwise function in public transport in these five counties. The SEPTA Transportation Board determines policy for the Authority. Its 15 members represent the five counties served by SEPTA and the governing bodies of the Commonwealth. Copyright SEPTA 2010. Pasquale T. Deon, Sr. James C. Schwartzman, Esquire Denise J. Smyler, Esquire Honorable Stewart J. Frank G. McCartney Herman M. Wooden Greenleaf, Esquire Beverly Coleman Rina Cutler Thomas E. Babcock Joseph E. Brion, Esquire Thomas Jay Ellis, Kevin L. -

Cara Schneider (215) 599-0789, [email protected] Deirdre Childress Hopkins (215) 599-2291, [email protected] Tweet Us: @Visitphillypr

CONTACTS: Cara Schneider (215) 599-0789, [email protected] Deirdre Childress Hopkins (215) 599-2291, [email protected] Tweet Us: @visitphillyPR Tweet It: The how-tos of must-dos when you @visitphilly: https://vstphl.ly/2LMm5lA PHILLY 101: THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO NAVIGATING PHILADELPHIA Primer On The City’s Layout, Icons & Accents PHILADELPHIA, June 25, 2019 – Every year, visitors to Philadelphia get to know the city’s history, customs, cuisine, dialect and landscape during their visits. Both first-time travelers and returning natives discover and rediscover a diverse, neighborhood-based metropolis with a downtown that’s easy to navigate on one’s own or via public transit. Philly regularly receives raves in The New York Times, Bon Appétit, Travel + Leisure, USA Today and Condé Nast Traveler, yet doesn’t stand one bit for pretense. Here are the basics any visitor to Philadelphia should know: Well-Planned City: • Layout – Seventeenth-century city planner William Penn envisioned the grid of streets that comprise Philadelphia’s downtown, Center City. Perpendicular streets run north-south (they’re numbered) and east-west (many named for trees: Walnut, Locust, Spruce). What would be 1st Street is named Front Street. What would be 14th Street is Broad Street. Two rivers, the Schuylkill and the Delaware (dividing Pennsylvania from New Jersey), form the western and eastern boundaries of Center City; Vine Street and South Street form north-south boundaries. Today, Penn continues to give direction to the city. His statue atop City Hall points northeast. • Exceptions to the Layout – The 101-year-old, mile-long Benjamin Franklin Parkway cuts diagonally through Center City’s grid, from near City Hall, past the famous LOVE Park to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. -

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Clichés Rule the Thinking of Most People Who Comment on Philadelphia Without Knowing the 1990S Version of the City

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Clichés rule the thinking of most people who comment on Philadelphia without knowing the 1990s version of the city. The standard knock is that it’s unhip—the place W.C. Fields thought would be a mite better than six feet under, the spiritual and real home of Dick Clark and his ’50s bandstand beat, the old-fashioned “City of Firsts’’ that never threw off the arts stigma of being Constitution City, birthplace of the nation. A second cliché is that it operates in the shadow of New York. Doesn’t everyone just drive up to Manhattan when an urge for real culture hits? Don’t Philadelphia artists tremble at what New Yorkers think of their work? Don’t Philadelphia audiences diss their local wares as second-rate stuff? The images are as stale as a week-old non- Philadelphia pretzel to those who know. Philadelphia’s arts scene—from historic insti- tutions like The Philadelphia Orchestra to the fast-growing Philadelphia Fringe Festival, from touring Broadway companies to the area’s more than 20 innovative theaters—is bigger and more vibrant than at any point in the city’s history. In recent years, Mayor Ed Rendell has com- mitted his administration to creating an “Avenue of the Arts” with 16 new and renovated arts facil- ities on the city’s South Broad Street— Philadelphia’s historic arts thoroughfare. Private philanthropy has also kicked in. The result so far is three newly constructed playhouses, including a smashing new space for the Wilma Theater and the just-reopened Prince Music Theater, which will serve as base for the former American Music Theater Festival, now renamed the “Prince Music Theater” after its new home. -

Co-Producing Commercial Safety Services in Philadelphia

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Co-Producing Commercial Safety Services in Philadelphia Author(s): Robert J. Stokes ; Brian Lawton ; Kristen Henderson ; Jack R. Greene Document No.: 216345 Date Received: November 2006 Award Number: 97-IJ-CX-0049 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Co-Producing Commercial Safety Services in Philadelphia Final Report by Robert J. Stokes Brian Lawton Kirsten Henderson Jack R. Greene Center for Public Policy Temple University Philadelphia, PA The research reported here was supported by Grant # 1997-IJ-CX-0049 from the U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice (NIJ). Opinions expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. -

Artsguide Philadelphia

ALA Midwinter Meeting, January 24-28, 2014 ArtsGuide Philadelphia American Library Association Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Arts Section ArtsGuide Philadelphia | 1 ALA Midwinter Meeting, January 24-28, 2014 Introduction Welcome to the ACRL Arts Section’s ArtsGuide Philadelphia! This selective guide to cultural attractions and events has been created for attendees of the 2014 ALA Midwinter Meeting in Philadelphia, PA. Map of sites listed in this guide - See what’s close to you or plot your course by car, foot, or public transportation using the Google Map version of this guide: https://mapsengine.google.com/map/edit?mid=zqJ- Ed3bmpRo.kk2kwWFt8ygQ Pennsylvania Convention Center 1101 Arch Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 (215) 418-4700 Local Transportation . http://www.visitphilly.com/getting-around/ . http://alamw14.ala.org/local-transportation (**Note: SEPTA service schedules change throughout the day, please confirm availability of Public Transportation with the intended time of your visit. http://www.septa.org **) Where to search for arts and entertainment . VisitPhilly.com : Official Visitor Site for Greater Philadelphia http://www.visitphilly.com/things-to-do/ . Philadelphia’s Official Convention & Visitors Site http://www.discoverphl.com . Philly Fun Guide http://www.phillyfunguide.com . Philadelphia Weekly or City Paper’s events listing http://www.philadelphiaweekly.com/events/ http://citypaper.net/agenda/ This guide has been edited and formatted by: Bridget O’Donnell (New York University) Contributors: Claudia Covert (Rhode Island School of Design) Bridget O’Donnell, editor (New York University) Lauren McDonald (California College of Arts) Ariel Turner (Kennesaw State University) *Efforts were made to gather the most up to date information but please be sure to check the web sites provided. -

A River Runs Through Them: the Story of Philadelphia and Camden's

a river runs through them By Thomas Corcoran, Anthony Perno, III, and Jenny Greenberg Credit: Cooper’s Ferry Partnership have worked to re-invent their downtown waterfronts as regional destinations offering a mix of large-scale family Thomas Corcoran entertainment attractions, public events, festivals, con- is the president of certs, and fireworks displays. the Delaware River Waterfront Today, the master plans for Philadelphia and Cam- Corporation. den include significant low-to-mid-rise housing com- ([email protected]) ponents, integrated with retail and restaurants along with public amenities including parks and trails. Phila- Anthony Perno is delphia and Camden have come to view their down- chief executive officer town waterfronts as assets that must be leveraged to of Cooper’s Ferry serve residents of the city and region, as well as visitors. Partnership. (perno@ coopersferry.com) Today, employment in education and the health services sector has replaced industrial activity as the Jenny Greenberg principal driver in Philadelphia and Camden. The “eds is a fundraising and meds” account for 43 percent of employment in consultant and Camden and 37 percent in Philadelphia. (The Camden writer, who works Higher Education and Healthcare Task Force: A Winning on both sides of the Visitors disembark from the RiverLink Ferry on the Camden waterfront. Waterfront. The RiverLink provides a fun and scenic way to travel Investment for the City of Camden, 2012) In both cities, educational and medical institutions attract knowledge (jgreenberg@ between the two sides of Philadelphia and Camden’s growing drwc.org) regional waterfront destination. workers who are seeking amenities including vibrant waterfronts.