Opposition to Attorney General's Petition for Declaratory Judgment In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JULY-AUGUST 1980 in 1980 Session: Lawmakers Did Some Good Repair Work

PUBLISHED BY THE FLORIDA SHERIFFS ASSOCIATION JULY-AUGUST 1980 In 1980 Session: Lawmakers Did Some Good Repair Work From a law enforcement perspective, the 1980 seized in drug busts) were cleaned up and pow wow of the Florida Legislature was a generally streamlined. productive toughen up, tighten up, fix up, clean up Florida's laws relating to sovereign immunity and shape up session. for public officials were fixed up in a way that The lawmakers got tough with "head shop" clarifies the status of Sheriffs and deputies. operators who sell drug paraphernalia, and also Sheriffs applauded when a law relating to non- with convicted drug traffickers. They practically criminal mentally ill persons was reshaped to put the head shop guys out of business, and they absolutely prohibit mental patients from being made it impossible for the drug wheelers and confined in county jails. dealers to go free under bail while their All in all the lawmakers did some good repair convictions are under appeal. and renovation jobs. Details of their handiwork Sheriffs' procedures for disposing ofcontraband will be found in the following summaries of 1980 items (for example, boats, airplanes and trucks laws relating to the criminal justice system: Chapter 80-27 (Committee Substitute for House lyzing, packaging, repackaging, storing, containing, Bills 532 k 630) concealing, injecting, ingesting, inhaling, or otherwise An Attorney General's opinion ruled that Florida law introducing into the human body a controlled sub- enforcement agencies are prohibited from intercepting stance. .." Among the items specifically outlawed are and recording their own telephone lines. This law erases water pipes, chamber pipes, electrical pipes, air-driven the prohibition by specifically authorizing law enforce- pipes, chillums, bongs, cocaine spoons and roach clips. -

The Journal of the House of Representatives

The Journal OF THE House of Representatives Number 1 Tuesday, March 6, 2001 Journal of the House of Representatives for the 103rd Regular Session since Statehood in 1845, convened under the Constitution of 1968, begun and held at the Capitol in the City of Tallahassee in the State of Florida on Tuesday, March 6, 2001, being the day fixed by the Constitution for the purpose. This being the day fixed by the Constitution for the convening of the Ausley Diaz-Balart Jordan Paul Legislature, the Members of the House of Representatives met in the Baker Dockery Joyner Peterman Chamber at 9:50 a.m. for the beginning of the 103rd Regular Session Ball Farkas Justice Pickens and were called to order by the Honorable Tom Feeney, Speaker. Barreiro Fasano Kallinger Prieguez Baxley Fields Kendrick Rich Prayer Bean Fiorentino Kilmer Richardson The following prayer was offered by the Reverend James Jennings of Bendross-Mindingall Flanagan Kosmas Ritter First United Methodist Church of Sarasota, upon invitation of Rep. Bennett Frankel Kottkamp Romeo Clarke: Bense Gannon Kravitz Ross Benson Garcia Kyle Rubio God of our beginnings and our endings, God of the Passover, Easter, Berfield Gardiner Lacasa Russell God of the pilgrims to Mecca, Alpha and Omega of the whole universe, Betancourt Gelber Lee Ryan bless this assembly with Your mercy and Your grace. We give You Bilirakis Gibson Lerner Seiler thanks for this day of new beginnings. But, O God, as we begin this day, Bowen Goodlette Littlefield Simmons our hearts are heavy for the shooting at Santana High School in Brown Gottlieb Lynn Siplin California. -

Religion, Sex & Politics: the Story of the Equal Rights Amendment in Florida

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Religion, Sex & Politics: The Story of the Equal Rights Amendment in Florida Laura E. Brock Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES RELIGION, SEX & POLITICS: THE STORY OF THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT IN FLORIDA By LAURA E. BROCK A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Laura E. Brock All Rights Reserved Laura E. Brock defended this dissertation on June 24, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Amanda Porterfield Professor Directing Dissertation Deana A. Rohlinger University Representative John Corrigan Committee Member John Kelsay Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my mother, Ruth Brock (1932 – 2010), my father, Roy Brock, and my brother, Caleb Brock. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to the dozens of people who encouraged and helped me complete this project while I worked full-time and spent every spare minute researching and writing. The bright world of scholarship at Florida State University has enriched my life immeasurably and I owe a debt of gratitude to those who embody that world. My deepest thanks go to my advisor, Amanda Porterfield, for guiding me through this project after expanding my mind and intellect in so many positive ways. -

Supreme Court of Florida in Re: 2002 Joint Resolution

SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA IN RE: 2002 JOINT RESOLUTION CASE NO. SC02-194 OF APPORTIONMENT __________________________________/ REQUEST TO PARTICIPATE FOR ORAL ARGUMENT Petitioners Raul L. Martinez, Bishop Victor T. Curry and the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project, respectfully request that their counsel be permitted to participate in the oral argument in this proceeding. Respectfully submitted this 17th day of April, 2002. Respectfully submitted, Dated: April, ___, 2002 LAW OFFICES BILIZIN SUMBERG DUNN WILLIAMS & ASSOCIATES, P.A. BAENA PRICE & AXELROD LLP Brickell Bay View Centre, 200 South Biscayne Blvd. Suite 1830 Suite 2500 Miami, Florida 33131 Miami, Florida 33131 Telephone 305-379-6676 Telephone 305-375-6144 Facsimile 305-379-4541 Facsimile 305-375-6146 By: _________________________ By: ______________________ THOMASINA H. WILLIAMS NORMAN C. POWELL FLORIDA BAR NO. 629227 FLORIDA BAR NO. 870536 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I HEREBY CERTIFY that a true and correct copy of the foregoing was served by U.S. Mail on those parties on the attached service list on this___ day of April, 2002. ____________________________ By: NORMAN C. POWELL CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE I HEREBY CERTIFY that the foregoing was prepared with 14-point Times Roman in compliance with Fl. R. App. P. 9210(a)(2). _____________________________ By: NORMAN C. POWELL 2 SERVICE LIST AS OF APRIL 17, 2002 REPRESENTATIVE FOR RICHARD L. STEINBERG, SIMON CRUZ, BRUCE M. SINGER, SAUL GROSS, LINDA CHARLENE BARNETT, RONALD G. STONE, BRIAN SMITH, JOSE SMITH, LENORE FLEMING, GERALD K. AND DEBRA H. SCHWARTZ, TERRI ECHARTE, GUILLERMO ECHARTE, DAVID M. DOBIN, MIKE GIBALDI, SUSAN FLEMING, LESLIE COLLER, KATHRYN BLAKEMAN, SALLY SIMS BARNETT, WENDY S. -

SUPREME COURT of FLORIDA Case No. SC02-194 the FLORIDA

SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA Case No. SC02-194 IN RE: 2002 JOINT RESOLUTION OF APPORTIONMENT THE FLORIDA SENATE’S NOTICE OF ORAL ARGUMENT DIVISION The Florida Senate and the Florida House of Representatives have agreed that each will take one-half hour of the one hour allotted to them as proponents. The Senate will divide its time as follows: Initial presentation: Barry Richard (20 minutes) Rebuttal: Barry Richard (7 minutes) James Scott (3 minutes) JAMES A. SCOTT BARRY RICHARD Tripp Scott, P.A. Greenberg Traurig, P.A. P.O. Box 14245 P.O. Drawer 1838 Ft. Lauderdale, FL 33302 Tallahassee, FL 32302 Florida Bar No.: 105599 _________________________ CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I HEREBY CERTIFY that a true and correct copy of the foregoing has been furnished by U.S. Mail to the parties on the attached list this 19th day of April, 2002: ____________________________________ BARRY RICHARD IN RE: 2002 JOINT RESOLUTION OF APPORTIONMENT CASE NO. SC02-194 COMMENT OF MALCOLM E. MCLOUTH Malcolm E. McLouth (4/16/2002) Executive Director Canaveral Port Authority Post Office Box 267 Cape Canaveral, Florida 32920 COMMENT OF ANDREW PORTER Andrew Porter (4/16/2002) Route 10, Box 886 Lake City, Florida 32025 COMMENT OF ROLAND F. HOTARD, III Mayor Roland F. Hotard, III (4/16/2002) City of Winter Park 401 Park Avenue S. Winter Park, Florida 32789 COMMENT OF LANE GILCHRIST Mayor Lane Gilchrist (4/16/2002) City of Gulf Breeze 1070 Shoreline Drive Gulf Breeze, Florida 32561 COMMENT OF JOANNE FLORIN Joanne Florin (4/16/2002) 3106 Columns Circle Seminole, Florida 33772 COMMENT OF DENISE KUHN Denise Kuhn (4/16/2002) 14189 Fennsbury Drive Tampa, Florida 33624 COMMENT OF MARK MOORE Mark Moore (4/16/2002) 4721 Riverside Drive, Box 9 Yankeetown, Florida 34498 COMMENT OF THOMAS VOURLOS Thomas Vourlos (4/16/2002) 1711 Cypress Avenue Belleair, Florida 33756 COMMENT OF GREATER PALM BAY CHAMBER Stephen Sherbin (4/16/2002) Chairman of Board of Directors Greater Palm Bay Chamber 1153 Malabar Road #18 Palm Bay, Florida 32907 COMMENT OF J.J. -

Constitutionality of House Joint Resolution 1987

Supreme Court of Florida ____________ No. SC02-194 ____________ IN RE: CONSTITUTIONALITY OF HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 1987. [ May 3, 2002 ] HARDING, J. This is an original proceeding in which the Attorney General petitions this Court for a declaratory judgment determining the validity of House Joint Resolution 1987 apportioning the Legislature of the State of Florida . We have jurisdiction under article III, section 16(c) of the Florida Constitution, which provides: JUDICIAL REVIEW OF APPORTIONMENT. Within fifteen days after the passage of the joint resolution of apportionment, the attorney general shall petition the supreme court of the state for a declaratory judgment determining the validity of the apportionment. The supreme court, in accordance with its rules, shall permit adversary interests to present their views and, within thirty days from the filing of the petition, shall enter its judgment. On March 22, 2002 , the Legislature passed House Joint Resolution 1987, which apportions the Florida Senate and House of Representatives based on the population figures established in the 2000 census. The Attorney General filed this -2- declaratory judgment petition on April 8, 2002 , and this Court invited all those interested to submit briefs and comments in support of or opposition to the plan and to participate in oral argument before the Court. We begin our analysis by addressing the scope of this Court’s review in the instant proceeding. Our review afforded under article III, section 16(c) is extremely limited. In our first opinion examining the jurisdictional basis of article III, section 16(c), Florida Constitution, after its adoption, we observed: At the outset, we emphasize that legislative reapportionment is primarily a matter for legislative consideration and determination. -

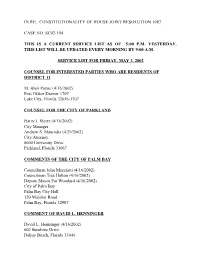

In Re: Constitutionality of House Joint Resolution 1987

IN RE: CONSTITUTIONALITY OF HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 1987 CASE NO. SC02-194 THIS IS A CURRENT SERVICE LIST AS OF 5:00 P.M. YESTERDAY. THIS LIST WILL BE UPDATED EVERY MORNING BY 9:00 A.M. SERVICE LIST FOR FRIDAY, MAY 3, 2002 COUNSEL FOR INTERESTED PARTIES WHO ARE RESIDENTS OF DISTRICT 11 M. Blair Payne (4/16/2002) Post Office Drawer 1707 Lake City, Florida 32056-1707 COUNSEL FOR THE CITY OF PARKLAND Harry J. Mertz (4/16/2002) City Manager Andrew S. Maurodis (4/29/2002) City Attorney 6600 University Drive Parkland, Florida 33067 COMMENTS OF THE CITY OF PALM BAY Councilman John Mazziotti (4/16/2002) Councilman Tres Holton (4/16/2002) Deputy Mayor Pat Woodard (4/16/2002) City of Palm Bay Palm Bay City Hall 120 Malabar Road Palm Bay, Florida 32907 COMMENT OF DAVID L. HENNINGER David L. Henninger (4/16/2002) 602 Sunshine Drive Delray Beach, Florida 33444 COMMENT OF MARLENE CLAUSEN Marlene Clausen (4/16/2002) 19450 Gulf Boulevard #205 Indian Shores, Florida 33785 COMMENT OF BRAD LEVINE Brad Levine (4/16/2002) 628 S.E. 5th Street #1 Delray Beach, Florida 33483 COMMENT OF G. PAUL CLARK G. Paul Clark (4/16/2002) 2020 S.E. 25th Street Ocala, Florida 34474 COMMENT OF ED GRAY, III Ed Gray, III (4/16/2002) 92 Chanteclaire Circle Gulf Breeze, Florida 32561 COMMENT OF LLOYD A. GREEN Mayor Lloyd A. Green (4/16/2002) City of Keystone Heights 335 S.E. Lakeview Drive Keystone Heights, Florida 32656 COMMENT OF DAVID MILLER David Miller (4/16/2002) 1631 S.W. -

1 EA Winter-FINAL

EMPLOYER Winter 2002 • Vol. 2, No. 1 F i n a n c e & T a x a t i o n Reviewing Exemptions the Right Way By Curt Leonard usher it through the legislative process. enate President John McKay (R- McKay defenders would point out, with Bradenton) is wending his way some justification, that the release of a bill of Sthrough Florida on a public speaking this scope simply lets critics pick it to pieces tour in an attempt to build support for before it ever gets a hearing. Liberating that reform of Florida’s tax structure. proposal to public scrutiny, however, makes In speech after speech, he is sharing his more sense from a political and a policy concerns about Florida’s current tax struc- standpoint. At the minimum, you find out ture, predicting tough times unless it is quickly whom your enemies are, which gives reformed, and promising a more stable fiscal you an opportunity to win them over by future for Florida if his plan is enacted. fixing any flaws in your proposal. Something His ambitious project could not come at a this complex can’t be rammed through the worse time, both economically and politically. Legislature. Quick on the heels of the December special In addition, the idea of tax reform in Florida What’s Inside session when they patched a $1.3 billion hole is akin to the Flat Earth Society announcing it in the 2001-02 fiscal-year budget, lawmakers will be looking for other options to explain Common Sense are now dreading a repeat of the exercise in our planet’s circumference: there just aren’t The Political Fires the 2002 regular session. -

The Journal of the House of Representatives

The Journal OF THE House of Representatives Number 1 Tuesday, January 22, 2002 Journal of the House of Representatives for the 104th Regular Session since Statehood in 1845, convened under the Constitution of 1968, begun and held at the Capitol in the City of Tallahassee in the State of Florida on Tuesday, January 22, 2002, being the day fixed by the Constitution and Chapter Law 2001-128, Laws of Florida, for the purpose. This being the day fixed by the Constitution and Chapter Law 2001- seems dim. Grant us hope and courage equal to the task. Give us the 128, Laws of Florida, for the convening of the Legislature, the Members inspiration to face the tests that will challenge us. And when obstacles of the House of Representatives met in the Chamber at 10:00 a.m. for arise, give us the faith to move forward in Your name. the beginning of the 104th Regular Session and were called to order by the Honorable Tom Feeney, Speaker. Almighty God, as the issues and concerns that affect the people of this great state of Florida are debated, help us to feel another’s woe, Announcements especially those whose quality of life is impacted by underdeveloped communities and economic decay. Help us to discern the good from ill, Representative Goodlette announced that Dr. Richard S. “Dick” and help us to overlook the faults we see, so that we can show mercy Hodes, who served in the House Chamber from 1966 to 1982 and served towards others. Give us a mind that is not bound, that does not as Speaker pro tempore in 1979 and 1980, died on Friday of last week. -

1 Ea Summer-02

EMPLOYER Summer 2002 • Vol. 2, No. 2 F i n a n c e & T a x a t i o n My Kingdom for Tax Reform by Curt Leonard plodding demeanor, provided the only true enate President John McKay (R- diligent and prudent leadership, taking the Bradenton) entered the 2002 Regular time necessary to scrutinize the proposal and SSession of the Florida Legislature with solicit public input. a mission: Enact something, anything, that gave voters the opportunity to use the state’s First, Kill All the Exemptions constitution as a cudgel to force the legisla- In January, after months of secrecy, What’s Inside ture to rewrite the sales-tax code. McKay’s plan was introduced as Senate Joint McKay and his Senate cohorts believe that Resolution 938, under the sponsorship of Sen. Common Sense: the legislature — an institution that recently Ken Pruitt (R-Port St. Lucie), the powerful Running the Clock adopted dramatic reforms in education chairman of the Senate Finance and Taxation by Jon L. Shebel governance, civil service, and tort law — is Committee. The constitutional amendment incapable of executing, all on its own, an embodied in SJR 938 reduced the sales-tax Caveat Banana orderly review of sales-tax exemptions. Sen. rate from six percent to four percent, effective by Curt Leonard McKay made it clear that, unless his quest July 1, 2004. On that date all current sales tax was successful, he was prepared to pitch exemptions, except for those on purchases of Double Trouble overboard the state budget, redistricting, the groceries, medicine, health care, and residen- by Jacquelyn Horkan Republican Party, and the political futures of tial rent, would disappear. -

Florida's Labor History Symposium (November 18, 1989). Proceedings. / INSTITUTION Florida International Univ., Miami

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 344 799 SO 021 423 AUTHOR Wilson, Margaret Gibbons, Ed. TITLE Florida's Labor History Symposium (November 18, 1989). Proceedings. / INSTITUTION Florida International Univ., Miami. Center for Labor Research and Studies. SPONS AGENCY Florida Endowment for the Humanities, Tampa. PUB DATE 91 NOTE 113p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Labor Force; Labor Relations; *Oral History; *State History; *Unions; Womens Studies; Working Class IDENTIFIERS *Florida; *Labor Studies ABSTRACT This document contains the proceedings from a one-day symposium designed to illuminate the history of the labor movement in Florida. The proceadings are organized into two parts: Part 1 "Topics in Florida Labor History" features "Labor History in Florida: What Do We Know? Where Do We Go?" (R. Zieger); "Workers' Culture and Women's Culture in Cigar Cities" (N. Hewitt); "Organizing Fishermen in Florida: The 1930s and 1940s" (B. Green); "Farmworkers and Farmworkers' Unions in Florida" (D. M. Barry); "Shadows from the Past: Documentary Film Making in Florida's Fields" (J. Applebaum); and "Oral History: Building Blocks for Historical Research" (S. Proctor). Part 2 is entitled "Recollections from the Past: The Florida Labor Movement from a Personal Perspective." This part contains the remarks given at the symposium 1-4 eight persons from the private sector: Andrew E. Dann, Sr., Gene C. Russo, Pernell Parker, and Joseph H. Kaplan and four from the public sector: Glbert Porter, Rodney Davis, Charles Hall, and James Sherman. (DB) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** U S. -

Moffitt Cancer Center: Leadership, Culture and Transformation

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School November 2018 Moffitta C ncer Center: Leadership, Culture and Transformation W. James Wilson University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons Scholar Commons Citation Wilson, W. James, "Moffitta C ncer Center: Leadership, Culture and Transformation" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7594 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moffitt Cancer Center: Leadership, Culture and Transformation by W. James Wilson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Business Administration Muma College of Business University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Timothy B. Heath, PhD Co-Major Professor: James A. Stikeleather, DBA Eric M. Eisenberg, PhD Joann Farrell Quinn, PhD, MBA Date of Approval: November 14, 2018 Keywords: decisions, founder, interdisciplinary, transformation, visionary Copyright © 2018, W. James Wilson DEDICATION To all who suffer from cancer. To the visionary leadership of a founder and leaders who created a transformational institution. To the physicians and care professionals who impact the lives of patients. To the brilliant researchers who dedicate themselves to discovery to eradicate the burden of cancer. To all who contribute to the prevention and cure of cancer. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the guidance, support and encouragement from the Co-Chairs and Members of the Dissertation Committee: Timothy B.