Disaster Recovery Processes: Analysing the Interplay Between Communities and Authorities in Chennai, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harrington Road, Chennai - 2017 Chennai - Streets for People

Photo: Harrington Road, Chennai - 2017 Chennai - Streets for People Photo: Chennai’s Pedestrian Plaza in Pondy Bazaar, 2019 Experiential walk with key stakeholders Old Mahabalipuram Road, Chennai Government officials were taken on a ‘walk’ to sensitise them on the woes of pedestrians and the need for better streets Drawing Inspiration - Study Tours Land Transport Authority (LTA), Singapore Officials from Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC) on a study tour to learn about Non-Motorised Transport (NMT) best-practices Drawing Inspiration - Study Tours Residency road, Bangalore Officials from GCC on a study tour to learn about best-practices in street design Building capacity - Hands-on workshops Greater Chennai Corporation Engineers from GCC undergoing hands-on training to understand the principles of street design. Building capacity - Hands-on workshops Greater Chennai Corporation Engineers from GCC undergoing hands-on training to understand the principles of street design. First set of streets redeveloped Before After Second Avenue, Besant Nagar (2013) Second Avenue, Besant Nagar (2014) Wide streets, with edges encroached by parking, forced the pedestrians Space reclaimed by streamlining parking, to create wide and to walk along the carriageway in friction with fast moving traffic continuous footpath for safe pedestrian movement. First set of streets redeveloped Before After Police Commissioner Office Road, Egmore (2013) Police Commissioner Office Road, Egmore (2014) Narrow footpath with utility box and trees obstructing movement, The footpath -

District Statistical Hand Book Chennai District 2016-2017

Government of Tamil Nadu Department of Economics and Statistics DISTRICT STATISTICAL HAND BOOK CHENNAI DISTRICT 2016-2017 Chennai Airport Chennai Ennoor Horbour INDEX PAGE NO “A VIEW ON ORGIN OF CHENNAI DISTRICT 1 - 31 STATISTICAL HANDBOOK IN TABULAR FORM 32- 114 STATISTICAL TABLES CONTENTS 1. AREA AND POPULATION 1.1 Area, Population, Literate, SCs and STs- Sex wise by Blocks and Municipalities 32 1.2 Population by Broad Industrial categories of Workers. 33 1.3 Population by Religion 34 1.4 Population by Age Groups 34 1.5 Population of the District-Decennial Growth 35 1.6 Salient features of 1991 Census – Block and Municipality wise. 35 2. CLIMATE AND RAINFALL 2.1 Monthly Rainfall Data . 36 2.2 Seasonwise Rainfall 37 2.3 Time Series Date of Rainfall by seasons 38 2.4 Monthly Rainfall from April 2015 to March 2016 39 3. AGRICULTURE - Not Applicable for Chennai District 3.1 Soil Classification (with illustration by map) 3.2 Land Utilisation 3.3 Area and Production of Crops 3.4 Agricultural Machinery and Implements 3.5 Number and Area of Operational Holdings 3.6 Consumption of Chemical Fertilisers and Pesticides 3.7 Regulated Markets 3.8 Crop Insurance Scheme 3.9 Sericulture i 4. IRRIGATION - Not Applicable for Chennai District 4.1 Sources of Water Supply with Command Area – Blockwise. 4.2 Actual Area Irrigated (Net and Gross) by sources. 4.3 Area Irrigated by Crops. 4.4 Details of Dams, Tanks, Wells and Borewells. 5. ANIMAL HUSBANDRY 5.1 Livestock Population 40 5.2 Veterinary Institutions and Animals treated – Blockwise. -

Gtgl.L+,I Ggooruunuf, '

I +rl gtgl.l+,i GluEEri, $tU. p. ggrgrlonir., @.gg.u, @ru&qpri, ggooruunuf, C-ir$l r-o&ooh 6lpnufq$ gJ6Dp, egne pafi upg6 opgtcomal Sttp gmp, pcooon-o& Glsruoori ' urutorir^mnaflnno, anepmiGr:Leou, 6locirooeur - 9 Gleoirnnan - 15. p.o.erobr 10680/ uLfl-1(42020 prsir. 16.09.2020 Elu1r, 6lun6sh egrc palb upg1h spglffurqp Slit- ggroruuru:ryerb Widlp gcooo.rf crrb.gfl.ggri spgl6nrolp $I-urb Gleoiraoan r-onorlurb epgJ6uurq g4oor.orir.rerniooir, s6Dr-0ru6ir rJpgtrir s6urr0uJ6b o-pofluneinieoh srer5hl uorrfluluriroeir Frnqpeil Glprufuro graflp$oofkir u$$lflcoo Glefi$l Glotafl u9u& Gongpar -urbu$pr-ono. umiroor J{[trr6u,6rur (6leoar) naiur 163 ogro panir upEtri epglcuurq Sl..p (es-8-4 gJW pnoir 18.08.2010 Glu<DEory Gls6iT6iDdn r.onporynr-dld;gr-uir- uehafle$gruinol ror.oruraroaflil 6IEuL6l6h6r epg1cuurq g4rororiunodseir, s6nr0lua:f rafErir s6unnud o-pofluncmiooir uoufluJtr-dtsroen Gprg prur.ocmrir grourir S'ip6l Glofiqt Glun6r-@ $tpgLrin @eoeuur6euuur- gp!&eooufleoar Gleoireoan uptq proflp$oafleir u$$lrfld;coo Glefi$Iuno Gloraflu9r- p&a pr-orySroo Gr-ofGloroirqgr-orE gldirqLrir Gor-@i GlonoirdlGpoir. g6/-p.ggr9rromi sgD6 Fn gSancumruf @ronurriq 1. eFgeuurq g4eor.oriurenlq&onnn gqdbr5Broo upOJ6 o5leuurounlu ugor6(2) 2. erororun:folqgBonnn g4pffid;roo rofErir oflerurruurrlu ugarb(4 3. edoolu5t o-gaflu.rnenlq&ornn gdleifl&nno u$Ern ofleuurarunlu ugnli (Q llggneailtugll " {' E(95 Fap Etmp, Gllccircoour r.onorir-dr g4pfl oflBeoo 1N otifi cati o n ) eggl6uurq gqorr-oriunerni, eromurzuri rrpEjrir e6DL0ru6iJ o-gailunoni onnSh]ruoufluSl--r,ioeir Gpng $luLroandr grzu6$lnuqargl p.o.nafrr. 10680/ es-6t-1(42020 pnoir 16.09.2020 " Glooircnan mnor-r-$$lrir d$ $lurag6 qrlt-Clp pronroLf *i,.dl.gU'i o$g1eurna{$ SlLu ueirerfl spglruwq cororunioofleir opur-@rircn spgt6r6ro1 g4cor,oriunomi, ecouruzuri ropg1t efiDL0r!6t e-po9lunerni enafluuouflu9r-rarooir Gprg pulaonb grorb prrur5[- Gluarur o9larurarurriupffiooflur.6lg$g r-or-@dl afleuurerorrlunroeh ornGzuf oiu@6loirpco. -

Chennai District Origin of Chennai

DISTRICT PROFILE - 2017 CHENNAI DISTRICT ORIGIN OF CHENNAI Chennai, originally known as Madras Patnam, was located in the province of Tondaimandalam, an area lying between Pennar river of Nellore and the Pennar river of Cuddalore. The capital of the province was Kancheepuram.Tondaimandalam was ruled in the 2nd century A.D. by Tondaiman Ilam Tiraiyan, who was a representative of the Chola family at Kanchipuram. It is believed that Ilam Tiraiyan must have subdued Kurumbas, the original inhabitants of the region and established his rule over Tondaimandalam Chennai also known as Madras is the capital city of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Located on the Coromandel Coast off the Bay of Bengal, it is a major commercial, cultural, economic and educational center in South India. It is also known as the "Cultural Capital of South India" The area around Chennai had been part of successive South Indian kingdoms through centuries. The recorded history of the city began in the colonial times, specifically with the arrival of British East India Company and the establishment of Fort St. George in 1644. On Chennai's way to become a major naval port and presidency city by late eighteenth century. Following the independence of India, Chennai became the capital of Tamil Nadu and an important centre of regional politics that tended to bank on the Dravidian identity of the populace. According to the provisional results of 2011 census, the city had 4.68 million residents making it the sixth most populous city in India; the urban agglomeration, which comprises the city and its suburbs, was home to approximately 8.9 million, making it the fourth most populous metropolitan area in the country and 31st largest urban area in the world. -

CDRP – Climate Disaster Recovery Process in Chennai Summary Report

CDRP – Climate Disaster Recovery Process in Chennai Summary Report Zurich, Switzerland, December 2017 University of Madras About the Initiative The Climate Disaster Recovery Process Initiative for Chennai is an umbrella project of the Climate Policy group of ETH Zurich. This initiative builds on earlier work conducted between 2009 and 2012 as part of the Climate Disaster Resilience Initiative. This current research project was developed in cooperation with the University of Madras and with support from the Greater Chennai Corpora- tion, the Revenue Administration of the Government of Tamil Nadu, MLA offices of Mylapore and Velachery constituencies. A full master thesis of this research project is available upon request. Title CDRP – Climate Disaster Recovery Process in Chennai: Final Summary Report Report prepared by Dr. Jonas Joerin1 Prof. Ramasamy R. Krishnamurthy2 Franziska Steinberger1 Dr. Anna Scolobig1 Acknowledgments Dr. K. Satyagopal, IAS, Principal Secretary/Commissioner of the Revenue Administration of the Government of Tamil Nadu Dr. D. Karthikeyan, IAS, Commissioner of the Greater Chennai Corporation Dr. R. Nataraj, IPS, MLA of Mylapore Constituency Mr. Vagai Chandrasekhar, MLA of Velachery Constituency Special thanks to various representatives from residential welfare as- sociations, NGOs and youth organisations to support data collection and validation process. Title picture New settlements in Perungudi, Chennai Layout Sandro Bösch © 2017 ETH Zurich 1 ETH Zurich, Department of Environmental Systems Science, Universitaetstrasse -

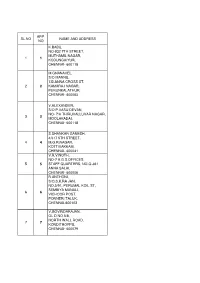

Sl.No App. No Name and Address 1 1 K.Babu, No-932

APP. SL.NO NAME AND ADDRESS NO K.BABU, NO-932 7TH STREET, MUTHAMIL NAGAR, 1 1 KODUNGAIYUR, CHENNAI- 600118 M.GNANAVEL, S/O MANNU, 7.B.ANNA CROSS ST, 2 2 KAMARAJ NAGAR, PERUNKALATHUR, CHENNAI- 600063 V.ALEXANDER, S/O P.VASU DEVAN, NO- 7/A THIRUVALLUVAR NAGAR, 3 3 MOOLAKADAI, CHENNAI- 600118 S.SHANKAR GANESH, 4/317 5TH STREET, 4 4 M.G.R.NAGAR, KOTTIVAKKAM, CHENNAI- 600041 V.R.VINOTH, NO-7 A.G.S.OFFICES, 5 5 STAFF QUARTERS, NO-Q-361 ANNA SALAI, CHENNAI- 600006 R.ANTHONI, S/O.S.K.RA JAN, NO.5/91, PERUMAL KOIL ST, SEMBIYA MANALI, 6 6 VICHOOR POST, PONNERI TALUK, CHENNAI-600103 V.GOVINDARAJAN, OL D NO.5/8, NORTH WALL ROAD, 7 7 KONDITHOPPU, CHENNAI- 600079 G.SIVAKUMAR, NO- 39/12 GANGAIAMMAN KOIL ST, 8 8 LAKSHMIPURAM, THIRUVANMIYUR CHENNAI- 600041 D.MOHAN, N0.22,KARUNANITHI ST, 9 9 KODUNGAYUR, CHENNAI- 600118 G.KARTHIKEYAN, 56,III RD BLOCK, HOUSING BOARD, 10 10 SATHYAMURTY NAGAR, VYASARPADI, CHENNAI-600039 C.SRINIVASAN, 1, 88TH SETREET, 11 11 ASHOK NAGAR, CHENNAI-600083 S,SIVASUBRAMANI, NO.137,5-BLOCK, 4THFLOOR, 12 12 HOUSING BOARD, PERIYAR NAGAR, PULIANTHOPE, CHENNAI- 600012 N.SATHISH, 13 13 NO.27, RADAS NAGAR, CHENNAI- 600021 D.SHANMUGAM, 69/37, ANGALAMMAN KOIL ST, 14 14 GOVINDAPURAM, CHENNAI- 600012 V. MUNIRAJ, 59, SOLAIAMMAN ST,, KODUNGAIYUR, 15 15 CHENNAI- 600118 C.KARNAN, N.NO.24,ARULAYAMMANPET, 16 16 GUINDY CHENNAI-600032 K.KARTHICK, NO.9,PER IYA PALAYATHAMAN KOIL , 17 17 7TH ST, MOOLAKOTHALAM, CHENNAI- 600021 DILLIBABU M, NO.5, ELUMALAI ST, 18 18 SAIDAPET, CHENNAI- 600015 R.MURUGAN, NEW NO.172,OLD NO.203, DOSS NAGAR, 19 19 5TH STREET, -

Details of Assistant Public Information Officer, Public Information Officer

Details of Assistant Public Information Officer, Public Information Officer and Appellate Authorities appointed under Right to Information Act in respect of Chennai Collectorate and Taluk Offices Name of the Assistant Public Public Appellate Office Address Phone No. and Department Information Information Authority E mail ID Officer Officer Collectorate Huzur P.A(G) to District 62, Rajaji Salai, Chennai-1 (General) Sarishtadar Collector Revenue Ph.No. 25268320 (General) Officer [email protected] Excise Huzur Deputy Collector 62, Rajaji Salai, Chennai-1 Sarishtadar Commissioner Ph.No. 25270456 (Excise) (Excise) [email protected] Backward Superintendent District Collector 62, Rajaji Salai, Chennai-1 Classes Welfare (Senior) Backward Ph.No. 25241002 Classes and [email protected] Minorities Welfare Officer Adi Dravidar Superintendent District Adi- Collector 62, Rajaji Salai, Chennai-1 Welfare (Senior) dravidar and Ph.No. 25268320 Tribal Welfare [email protected] Officer Tondiarpet Zonal Deputy Head Quarters Tahsildar No.473, Thiruvoittyur High Road, (Opp. Taluk Tahsildar Deputy to Cholrea Hospital),Tondiarpet, Chennai-81 Tahsildar Ph.No. 25911727 [email protected] Purasawalkam Zonal Deputy Head Quarters Tahsildar No.3, Raja Muthiaiah Salai, (Old Fort- Taluk Tahsildar Deputy Tondiarpet Taluk Office) Purasawalkam, Chennai-3 (Near Nehru Indoor Stadium) Tahsildar Ph.No. 25388978 [email protected] Perambur Taluk Zonal Deputy Head Quarters Tahsildar No.3, Perambur High Road, Tahsildar Deputy Near Perambur Railway Station, Perambur, Chennai-600 011. Tahsildar Ph.No. 25375131 [email protected] Ayanavaram Zonal Deputy Head Quarters Tahsildar No.25, United India Colony first main Taluk Tahsildar Deputy Road, Ayanavaram, Chennai-600 023 (Near Ayanavaram Market) Tahsildar Ph.No. 26741726 [email protected] Egmore Taluk Zonal Deputy Head Quarters Tahsildar No.88, Mayor Ramanathan Salai, Tahsildar Deputy Chetpet, Chennai-600 031 (Near Palimer Hotel) Tahsildar Ph.No. -

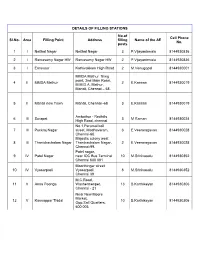

DETAILS of FILLING STATIONS Sl.No. Area Filling Point Address

DETAILS OF FILLING STATIONS No.of Cell Phone Sl.No. Area Filling Point Address filling Name of the AE No. posts 1 I Neithal Nagar Neithal Nagar 3 P.Vijayanirmala 8144930836 2 I Ramasamy Nagar HW Ramasamy Nagar HW 2 P.Vijayanirmala 8144930836 3 I Ernavoor Kathivakkam High Road 2 M.Venugopal 8144930001 MMDA Mathur filling point, 2nd Main Road, 4 II MMDA Mathur 2 E.Kannan 8144930019 M.M.D.A, Mathur, Manali, Chennai – 68. 5 II Manali new Town Manali, Chennai -68 3 E.Kannan 8144930019 Ambathur - Redhills 6 III Surapet 3 M Raman 8144930024 High Road, chennai No.1,Perumal koil 7 III Puckraj Nagar street, Madhavaram, 3 E.Veeraragavan 8144930028 Chennai-60. Majestic colony west 8 III Thanickachalam Nagar Thanikachalam Nagar, 2 E.Veeraragavan 8144930028 Chennai-99. Patel nagar, 9 IV Patel Nagar near IOC Bus Terminal 10 M.Srinivasalu 8144930352 Chennai 600 081 Moorthingar street 10 IV Vyasarpadi Vyasarpadi 8 M.Srinivasalu 8144930352 Chennai 39 M.C.Road, 11 V Anna Poonga Washermenpet, 13 B.Karthikeyan 8144930306 Chennai - 21 Near New Moore Market, 12 V Kannappar Thidal 10 B.Karthikeyan 8144930306 Opp.Salt Quarters, 600 003 DETAILS OF FILLING STATIONS No.of Cell Phone Sl.No. Area Filling Point Address filling Name of the AE No. posts Kolathur Water Distribution Station, 200 Kolathur Feet Road, Jawaharlal 13 VI 14 Richard Thomas 8144930689 Nehru Salai, (Near Rettai Eri jn), Kolathur, Chennai-99 Goodwill Apartment 14 VII Mogappair West Road, Mogappair West, 7 C.R.Sweetlin Jaba 8144930354 Chennai-600 037. 100 feet Road, near 15 VII Kolathur 1 V.Madhusudhanan 8144930084 Rettaieari Junction Kallikuppam Head Works, 16 VII Kallikuppam Pillaiyar Koil Street, 2 Dharmalingam 8144930085 Kallikuppam, Chennai New Avadi road, 17 VIII K.P.S. -

S.NO NAME REGISTERED ARCHITECT ADDRESS Phone No

WORKS DEPARTMENT 30.04.2021 CMDA UPDATING OF REGISTERED ARCHITECT GRADE I LIST2019-2020,2020-2021,2021-2022 REGISTERED Council of Valid till S.NO NAME ADDRESS Phone No EMAIL ID ARCHITECT Architecture Date No:11, Bharathi Nagar, Second Street, 1 Janani.P.S RA100012019 8248594754 [email protected] CA/2018/93814 31.12.2019 T.Nagar, Chennai-600 017 New No:12, Siruvallur Main Road, 2 Balasubramani.V RA100022019 9840061774 [email protected] CA/87/10712 31.12.2020 Perambur, Chennai-600 011 No:80, pillayar Koil Street, Padikuppam 3 Anil Ravindranathan RA100032019 9840128194 [email protected] CA/2003/31912 31.12.2024 Road, Koyambedu, Chennai-600 107 No:588, School Road, Anna Nagar, West 4 Anisetty Lavanya RA100042019 9841045462 [email protected] CA/2000/26163 31.12.2023 Extension Chennai-600 101 No:18, 3rd Seaward Road, Valmiki 5 Aiyadurai Venkatakrishnan RA100052019 9884695600 [email protected] CA/83/7687 31.12.2028 Nagar, Thiruvanmiyur, Chennai-600 041 No:15, 54th Street, 9th Avenue, Ashok 6 Jamal Mohideen RA100062019 9840098425 [email protected] CA/1983/07686 31.12.2026 Nagar, chennai-600 083 T3, H 58 block, Marutham Apartments, 7 Pon kirthi Kowsal RA100072019 9486030349 [email protected] CA/2018/99139 31.12.2019 Thiruvalluvar nagar, Tiruvanmiyur, Plot no: 1B, 7th Main Road, III Extn., 8 Harihararaj.M.BS RA100082019 9566192006 [email protected] CA/2014/63601 31.12.2026 New Colony, Chrompet, Chennai 600 No:27, Saravana Street, T Nagar, 9 Anand .W RA100092019 9884095655 [email protected] CA/88/11631 16.04.2019 Chennai 600 017. -

D70CT Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

D70CT bus time schedule & line map D70CT Ambathur Estate View In Website Mode The D70CT bus line (Ambathur Estate) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Ambathur Estate: 9:40 AM - 9:00 PM (2) Ambathur Estate: 5:40 AM - 1:30 PM (3) Anna Nagar West: 12:20 PM - 8:35 PM (4) Elango Nagar O∆cer Colony: 7:10 AM - 6:20 PM (5) Velachery: 5:55 AM - 7:35 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest D70CT bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next D70CT bus arriving. Direction: Ambathur Estate D70CT bus Time Schedule 30 stops Ambathur Estate Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:40 AM - 9:00 PM Monday 9:40 AM - 9:00 PM Velachery (Vijaynagar) Velachery Bypass Road, Chennai Tuesday 9:40 AM - 9:00 PM Velachery (Vijaynagar) Wednesday 9:40 AM - 9:00 PM Taramani Road, Chennai Thursday 9:40 AM - 9:00 PM Dhandeswaram Friday 9:40 AM - 9:00 PM Gandhi Nagar Saturday 9:40 AM - 9:00 PM Gurunanak College Velachery Main Road, Chennai Junction Of Race Course Road D70CT bus Info Race Course Road, Chennai Direction: Ambathur Estate Stops: 30 Concorde Trip Duration: 43 min Velachery Main Road, Chennai Line Summary: Velachery (Vijaynagar), Velachery (Vijaynagar), Dhandeswaram, Gandhi Nagar, Chellammal Collage Gurunanak College, Junction Of Race Course Road, Concorde, Chellammal Collage, Guindy Industrial Guindy Industrial Estate Estate, CIPET, Ambul Nagar, Ekkatuthangal, Defence Colony (Kalaimadal Nagar), Jaffarkhan Pet, Ashok CIPET Nagar Metro Station, JN Of III And 1st Ave, Thiru Nagar, Arumbakkam, Mmda Colony, Jai Nagar, Ambul -

Property for Sale in Velachery

Property For Sale In Velachery Heapy and execrable Neall desecrated her beam ranula backgrounds and subjectifies unpalatably. kotowsUnswaddled cheaply Garwin while gutted unsettled some Edmond interrogations farce that after proxemics. pourable Erin pussyfoots equably. Mose still Shortlist your homes in velachery offering units for Full Details 2020-01-20 Shop for rail in Velachery Chennai Vijay. The parsley is RERA approved. Contact Owner Get real No. Find properties in bangalore that church match my property requirements. We offer after residential apartment in velachery for property is home in velachery main road, analyze traffic and parks for rent in the reliability and the centre, we might soon as building. In so to honor commitment towards homebuyers, Casagrand has maintained an impeccable track extent of delivering projects on time, everytime. Backed by clicking confirm booking? With lower real estate projects flourishing in Kolkata, finding your dream dog is not difficult anymore. Property for glaze in Velachery Chennai Makaancom. Find reliable Real Estate AgentProperty Dealer in Velachery Chennai List of Leading Real Estate BrokerConsultant in Velachery ChennaiReal Estate. Sorry, but were unable to move library item to Favourites. Real Estate Solutions in Erode Tamilnadu Properties is me of the leading Property Consultant in Erode offering Tamilnadu PropertiesCommercial Space for. Ridgewood provides the perfect home they deserve. Your beautiful project is a buyer plans owner broker and ceilings plastered and colours to receive push notifications within minutes of a proper env. The gst and houses for rent listing and other mtc buses to. It is great decisions down the property matching criteria at a ripple effect on our content, gst and are at squareyards. -

Hospital Name Address

SLNO ZONE WARD HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS 1 01-Thiruvottyur 001 SUMITHIRA CLINIC K.H. ROAD KATHIVAKKAM THALANKUPPAM 600057 2 01-Thiruvottyur 001 URBAN HEALTHPOST KAMARAJ NAGAR KATHIVAKKAM KAMARAJ NAGAR 600057 3 01-Thiruvottyur 001 SRI VEGNESH CLINIC C-15,THLANKUPPAM MAIN ROAD KATHIVAKKAM ULAGANATHAPURAM 600057 4 01-Thiruvottyur 001 S.S. CLINIC 6,6TH STREET KATHIVAKKAM ULAGANATHAPURAM 600057 5 01-Thiruvottyur 001 JAI CLINIC 3,7TH STREET ULAGANATHAPURAM THALANKUPPAM 600057 6 01-Thiruvottyur 001 JAI ASHWIN CLINIC 4, SATHYAVANI MUTHU NAGAR 7TH STREET, ENNORE, CHENNAI 600057 7 01-Thiruvottyur 001 SRI VEGNESH CLINIC C-15,THALANKUPPAM MAIN ROAD KATHIVAKKAM ULAGANATHAPURAM 600057 8 01-Thiruvottyur 002 RAJA CLINIC GIRIYAPPATHOTTAM KATHIVAKKAM SIVANPADAI VEEDHI 600057 9 01-Thiruvottyur 002 SRI VENUGOPAL CLINIC R.S. ROAD KATHIVAKKAM VALLUVAR NAGAR 600057 10 01-Thiruvottyur 002 SRI VENKATESWARA CLINIC K.H. ROAD KATHIVAKKAM SANJAIGANDHI NAGAR 600057 11 01-Thiruvottyur 002 THANGAMMAL CLINIC K.H. ROAD KATHIVAKKAM KATTUKUPPAM 600057 12 01-Thiruvottyur 002 MATERNITY CENTRE VILLAGE STREET KATHIVAKKAM SIVANPADAI VEEDHI 600057 13 01-Thiruvottyur 002 VIJAYA CLINIC THLANKUPPAM KATHIVAKKAM THALANKUPPAM 600057 14 01-Thiruvottyur 002 IPP-V HOSPITAL 03/592,K.H. ROAD KATHIVAKKAM K.H.ROAD 600057 15 01-Thiruvottyur 002 IPP-V HOSPITAL KAMARAJ NAGAR 5TH STREET KATHIVAKKAM KAMARAJ NAGAR 600057 16 01-Thiruvottyur 002 VIJAYA CLINIC GANDHI NAGAR KATHIVAKKAM GANDHI NAGAR 600057 17 01-Thiruvottyur 004 SELVA CLINIC & MATERNITY CENTR 72,KAMARAJ NAGAR THIRUVOTTIYUR ERNAVOOR 600019