Ev29n2p116.Pdf (1.056Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaceta Oficial Órgano Del Gobierno Del Estado De Veracruz De Ignacio De La Llave Director General De La Editora De Gobierno Martín Quitano Martínez

GACETA OFICIAL ÓRGANO DEL GOBIERNO DEL ESTADO DE VERACRUZ DE IGNACIO DE LA LLAVE DIRECTOR GENERAL DE LA EDITORA DE GOBIERNO MARTÍN QUITANO MARTÍNEZ DIRECTOR DE LA GACETA OFICIAL IGNACIO PAZ SERRANO Calle Morelos No. 43. Col. Centro Tel. 817-81-54 Xalapa-Enríquez, Ver. Tomo CXCVIII Xalapa-Enríquez, Ver., viernes 6 de julio de 2018 Núm. Ext. 270 SUMARIO GOBIERNO DEL ESTADO CÓDIGO DE CONDUCTA DEL MUNICIPIO DE CÓRDOBA, VER. ——— folio 1046 PODER JUDICIAL ACUERDO NÚMERO TEJAV/05/04/18 POR EL QUE SE H. AYUNTAMIENTO DE TANTOYUCA, VER. AUTORIZA UNA PRÓRROGA DE CIENTO OCHENTA DÍAS ——— HÁBILES, PARA RESOLVER LOS ASUNTOS EN TRÁMITE QUE ACTA DE SESIÓN DE CABILDO EXTRAORDINARIA DE FECHA ÉSTE ORGANISMO PÚBLICO AUTÓNOMO RECIBIÓ DEL 12 DE ABRIL DE 2018 EN DONDE EL CABILDO APRUEBA EXTINTO TRIBUNAL DE LO CONTENCIOSO A DMINISTRA- LA ADJUDICACIÓN DE UN INMUEBLE RURAL, UBICADO EN TIVO DEL PODER JUDICIAL DEL ESTADO. LA LOCALIDAD DE BUENA VISTA CHILAPÉREZ DE ESTE folio 1166 MUNICIPIO, EL CUAL SERÁ DONADO AL IMSS. folio 1155 H. AYUNTAMIENTO DE CÓRDOBA, VER. ——— H. AYUNTAMIENTO DE TAMPICO ALTO, VER. ——— Dirección de Obras Públicas REGLAMENTO INTERNO PARA EL PERSONAL DE CONFIANZA DEL H. AYUNTAMIENTO DE CÓRDOBA, VER. CONVOCATORIA 001 folio 1044 SE CONVOCA A LOS INTERESADOS EN PARTICIPAR EN LA LICITACIÓN PÚBLICA NACIONAL NO. DOP-001-2018- LPN, RELATIVO A LA OBRA "REHABILITACIÓN DE CA- LLES Y CONSTRUCCIÓN DE GUARNICIONES Y BANQUETAS CÓDIGO DE ÉTICA DE LOS SERVIDORES PÚBLICOS DE LA DIVERSAS", EN LA LOCALIDAD DE LLANO DE BUSTOS, EN ADMINISTRACIÓN MUNICIPAL DE CÓRDOBA, VER. EL MUNICIPIO DE TAMPICO ALTO, VER. -

Honorable Ayuntamiento Constitucional De Tantoyuca, Ver

PROGRAMA DE FORTALECIMIENTO A LA TRANSVERSALIDAD DE LA PERSPECTIVA DE GÉNERO 2010 “POLÍTICAS PÚBLICAS ESTATALES Y MUNICIPALES PARA LA IGUALDAD ENTRE MUJERES Y HOMBRES EN EL ESTADO DE VERACRUZ Honorable Ayuntamiento Constitucional de Tantoyuca, Ver. BANDO DE POLICÍA Y GOBIERNO “Este Programa es de carácter público, no es patrocinado ni promovido por partido político alguno y sus recursos provienen de los impuestos que pagan todos los contribuyentes. Está prohibido el uso de este Programa con fines políticos, electorales, de lucro y otros distintos a los establecidos. Quien haga uso indebido de los recursos de este Programa deberá ser denunciado y sancionado de acuerdo con la ley aplicable y ante autoridad competente”. Gobierno del Estado de Veracruz – Llave Fidel Herrera Beltrán Gobernador del Estado Reynaldo Escobar Pérez Secretario de Gobierno Gobierno Municipal de Tantoyuca, Ver. Trinidad San Román Vera Presidente Municipal Constitucional Jesús Gilberto Lince Kelly Secretario del Ayuntamiento Félix Francisco Herrera Acosta Síndico Único REGIDORA 1ª Roberta Adalmira Díaz Azuara REGIDOR 2º Favio Cerecedo Tapia REGIDOR 3º Margarito Serna Del Ángel REGIDOR 4º Abel García Rivera REGIDORA 5ª María de Jesús Montiel Nava REGIDOR 6º Guilebaldo García Zenil REGIDOR 7º Juan Netzahualcóyotl Castillo Badillo REGIDOR 8º Bernardo Hernández Ana 2 3 Índice Presentación…………………………………………………………………….….…4 Capítulo I. Disposición Generales……………………………………………….….5 Capítulo II. Del Nombre y Escudo del Municipio………………………………………………………………………….…....5 Capítulo III. De los Fines del Municipio……………………………………………..6 Capítulo IV. Del Territorio Municipal……………………………………………..….7 Capítulo V. De la Organización Política Municipal………………………………….………………………………………........7 Capítulo VI. De las y los Habitantes, Vecinas y Vecinos del Municipio, sus Derechos y Obligaciones……………………………………….......8 Capítulo VII. Del Gobierno Municipal…………………………………………….....9 Capítulo VIII. -

Listado De Zonas De Supervisión

Listado de zonas de supervisión 2019 CLAVE NOMBRE N/P NOMBRE DEL CENTRO DEL 30ETH MUNICIPIO Acayucan "A" clave 30FTH0001U 1 Mecayapan 125D Mecayapan 2 Soconusco 204Q Soconusco 3 Lomas de Tacamichapan 207N Jáltipan 4 Corral Nuevo 210A Acayucan 5 Coacotla 224D Cosoleacaque 6 Oteapan 225C Oteapan 7 Dehesa 308L Acayucan 8 Hueyapan de Ocampo 382T Hueyapan de Ocampo 9 Santa Rosa Loma Larga 446N Hueyapan de Ocampo 10 Outa 461F Oluta 11 Colonia Lealtad 483R Soconusco 12 Hidalgo 521D Acayucan 13 Chogota 547L Soconusco 14 Piedra Labrada 556T Tatahuicapan de Juárez 15 Hidalgo 591Z Acayucan 16 Esperanza Malota 592Y Acayucan 17 Comejen 615S Acayucan 18 Minzapan 672J Pajapan 19 Agua Pinole 697S Acayucan 20 Chacalapa 718O Chinameca 21 Pitalillo 766Y Acayucan 22 Ranchoapan 780R Jáltipan 23 Ixhuapan 785M Mecayapan 24 Ejido la Virgen 791X Soconusco 25 Pilapillo 845K Tatahuicapan de Juárez 26 El Aguacate 878B Hueyapan de Ocampo 27 Ahuatepec 882O Jáltipan 28 El Hato 964Y Acayucan Acayucan "B" clave 30FTH0038H 1 Achotal 0116W San Juan Evangelista 2 San Juan Evangelista 0117V San Juan Evangelista 3 Cuatotolapan 122G Hueyapan de Ocampo 4 Villa Alta 0143T Texistepec 5 Soteapan 189O Soteapan 6 Tenochtitlan 0232M Texistepec 7 Villa Juanita 0253Z San Juan Evangelista 8 Zapoapan 447M Hueyapan de Ocampo 9 Campo Nuevo 0477G San Juan Evangelista 10 Col. José Ma. Morelos y Pavón 484Q Soteapan 11 Tierra y Libertad 485P Soteapan 12 Cerquilla 0546M San Juan Evangelista 13 El Tulín 550Z Soteapan 14 Lomas de Sogotegoyo 658Q Hueyapan de Ocampo 15 Buena Vista 683P Soteapan 16 Mirador Saltillo 748I Soteapan 17 Ocozotepec 749H Soteapan 18 Chacalapa 812T Hueyapan de Ocampo 19 Nacaxtle 813S Hueyapan de Ocampo 20 Gral. -

Dirección General De Gestión De Servicios De Salud Dirección De Gestión De Servicios De Salud

COMISIÓN NACIONAL DE PROTECCIÓN SOCIAL EN SALUD DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE GESTIÓN DE SERVICIOS DE SALUD DIRECCIÓN DE GESTIÓN DE SERVICIOS DE SALUD DIRECTORIO DE GESTORES DEL SEGURO POPULAR VERACRUZ NOMBRE DEL ESTABLECIMIENTO DE MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE(S) APELLIDO PATERNO APELLIDO MATERNO SALUD ACAJETE ACAJETE ACAJETE XÓCHITL CORTINA LINAS HOSPITAL GENERAL DE OLUTA- ACAYUCAN ACAYUCAN CYNTIA ILEANA CASTILLO LÓPEZ ACAYUCAN HOSPITAL GENERAL DE OLUTA- ACAYUCAN ACAYUCAN SPIRO YELADAQUI CIRIGO ACAYUCAN ACTOPAN ACTOPAN ACTOPAN XÓCHITL CORTINA LINAS ACTOPAN CHICUASEN CHICUASEN XÓCHITL CORTINA LINAS ACTOPAN PALMAS DE ABAJO PALMAS DE ABAJO XÓCHITL CORTINA LINAS TRAPICHE DEL ACTOPAN TRAPICHE DEL ROSARIO XÓCHITL CORTINA LINAS ROSARIO ACULA ACULA ACULA BETZABÉ GONZÁLEZ FLORES ACULA POZA HONDA POZA HONDA BETZABÉ GONZÁLEZ FLORES ACULTZINGO PUENTE GUADALUPE PUENTE GUADALUPE RAFAEL POCEROS DOMÍNGUEZ ACULTZINGO ACULTZINGO ACULTZINGO RAFAEL POCEROS DOMÍNGUEZ ÁLAMO TEMAPACHE ÁLAMO HOSPITAL GENERAL ÁLAMO RICARDO DE JESÚS OSORIO ALAMILLA CENTRO DE SALUD CON ALTO LUCERO DE ALTO LUCERO HOSPITALIZACIÓN DE ALTO LUCERO DE MARIELA VIVEROS ARIZMENDI GUTIÉRREZ BARRIOS G.B. COMISIÓN NACIONAL DE PROTECCIÓN SOCIAL EN SALUD DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE GESTIÓN DE SERVICIOS DE SALUD DIRECCIÓN DE GESTIÓN DE SERVICIOS DE SALUD DIRECTORIO DE GESTORES DEL SEGURO POPULAR VERACRUZ NOMBRE DEL ESTABLECIMIENTO DE MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE(S) APELLIDO PATERNO APELLIDO MATERNO SALUD ALTO LUCERO DE PALMA SOLA PALMA SOLA XÓCHITL CORTINA LINAS GUTIÉRREZ BARRIOS HOSPITAL GENERAL ALTOTONGA ALTOTONGA -

Descriptivo De La Distritacion Federal Veracruz Marzo 2017

DESCRIPTIVO DE LA DISTRITACION FEDERAL VERACRUZ MARZO 2017 DESCRIPTIVO DE LA DISTRITACION FEDERAL VERACRUZ REGISTRO FEDERAL DE ELECTORES Página 1 de 21 La entidad federativa de Veracruz se integra por 20 demarcaciones territoriales distritales electorales federales, conforme a la siguiente descripción: Distrito 01 Esta demarcación territorial distrital federal tiene su cabecera ubicada en la localidad PANUCO perteneciente al municipio PANUCO, asimismo, se integra por un total de 13 municipios, que son los siguientes: NARANJOS AMATLAN, integrado por 19 secciones: de la 0320 a la 0338. CITLALTEPETL, integrado por 9 secciones: de la 0695 a la 0703. CHINAMPA DE GOROSTIZA, integrado por 10 secciones: de la 1403 a la 1412. OZULUAMA, integrado por 29 secciones: de la 2776 a la 2804. PANUCO, integrado por 83 secciones: de la 2814 a la 2889 y de la 2891 a la 2897. PUEBLO VIEJO, integrado por 40 secciones: de la 3219 a la 3258. TAMALIN, integrado por 8 secciones: de la 3543 a la 3550. TAMIAHUA, integrado por 21 secciones: de la 3551 a la 3571. TAMPICO ALTO, integrado por 19 secciones: de la 3572 a la 3590. TANCOCO, integrado por 7 secciones: de la 3591 a la 3597. TANTIMA, integrado por 11 secciones: de la 3598 a la 3608. TEMPOAL, integrado por 30 secciones: de la 3706 a la 3735. REGISTRO FEDERAL DE ELECTORES Página 2 de 21 EL HIGO, integrado por 16 secciones: de la 4696 a la 4711. El distrito electoral 01 se conforma por un total de 302 secciones electorales. Distrito 02 Esta demarcación territorial distrital federal tiene su cabecera ubicada en la localidad TANTOYUCA perteneciente al municipio TANTOYUCA, asimismo, se integra por un total de 15 municipios, que son los siguientes: BENITO JUAREZ, integrado por 10 secciones: de la 0482 a la 0491. -

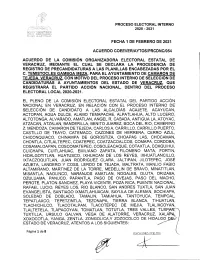

Proceso Electoral Interno 2020 - 2021 Comision • Oranizadora I

PROCESO ELECTORAL INTERNO 2020 - 2021 COMISION • ORANIZADORA I.. 4 ELECTO. FECHA 30 DE ENERO DE 2021 ACUERDO COEEVERIAYTOS/PRCDNC/013 ACUERDO DE LA COMISION ORGANIZADORA ELECTORAL ESTATAL DE VERACRUZ, MEDIANTE EL CUAL SE DECLARA LA PROCEDENCIA DE REGISTRO DE PRECANDIDATURA A LA PLANILLA ENCABEZADA POR LA C. MARIA DEL ROCiO GARCES CRUZ PARA EL AYUNTAMIENTO DE TLACHICHILCO, VERACRUZ, CON MOTIVO DEL PROCESO INTERNO DE SELECCION DE CANDIDATURAS A AYUNTAMIENTOS DEL ESTADO DE VERACRUZ QUE REGISTRARA EL PARTIDO ACCION NACIONAL, DENTRO DEL PROCESO ELECTORAL LOCAL 2020-2021. EL PLENO DE LA COMISION ELECTORAL ESTATAL DEL PARTIDO ACCION NACIONAL EN VERACRUZ, EN RELACION CON EL PROCESO INTERNO DE SELECCION DE CANDIDATO A LAS ALCALDIAS ACAJETE, ACAYUCAN, ACTOPAN, AGUA DULCE, ALAMO TEMAPACHE, ALPATLAHUA, ALTO LUCERO, ALTOTONGA, ALVARADO, AMATLAN, ANGEL R. CABADA, ANTIGUA LA, ATOYAC, ATZACAN, ATZALAN, BANDERILLA, BENITO JUAREZ, BOCA DEL RIO, CAMERINO Z. MENDOZA, CAMARON DE TEJEDA, CARLOS A. CARRILLO, CARRILLO PUERTO, CASTILLO DE TEAYO, CATEMACO, CAZONES DE HERRERA, CERRO AZUL, CHICONQUIACO, CHINAMPA DE GOROSTIZA, CHOAPAS LAS, CHOCAMAN, CHONTLA, CITLALTEPEC, COATEPEC, COATZACOALCOS, COMAPA, CORDOBA, COSAMALOAPAN, COSCOMATEPEC, COSOLEACAQUE, COTAXTLA, COXQUIHUI, CUICHAPA, CUITLAHUAC, EMILIANO ZAPATA, FILOMENO MATA, FORTIN, HIDALGOTITLAN, HUATUSCO, IXHUACAN DE LOS REYES, IXHUATLANCILLO, IXTACZOQUITLAN, JUAN RODRIGUEZ CLARA, JALTIPAN, JILOTEPEC, JOSE AZUETA, LANDERO Y COSS, LERDO DE TEJADA, MALTRATA, MANLIO FABIO ALTAMIRANO, MARTINEZ DE LA TORRE, MEDELLIN -

Tev-Jdc-56-2018 Acuerdo De Radicación Y Requerimiento

§\¡lDos TRIBUNAL ELECTORAL DE VERACRUZ SECREfARfA GENERAL DE ACUERDOS TRIBUNAL ELECTOR{L CEDULA DE NOTIFICACIÓN DE I'ERACRUZ JUICIO PARA LA PROTECCIÓN DE LOS DERECHOS POL¡fl CO.ELECTORALES DEL CIUDADANO. EXPEDIENTE: TEV- JDC-s61201 8. ACTORES: ÁIVERO ESTEBAN HERNÁNDEZ CAMARGO Y BLANCA ISABEL HERNÁNDEZ LARA. AUTORIDAD RESPONSABLE: JUNTA MUNICIPAL ELECTORAL DE TANTOYUCA, VERACRUZ. En Xalapa-Enríquez, Veracruz de lgnacio de la Llave; ocho de abril de dos mil dieciocho, con fundamento en los artículos 387 y 393 del Código Electoral del Estado de Veracruz, en relación con los numerales 50, 147 y 154 del Reglamento lnterior del Tribunal Electoral de Veracruz y en cumplimiento de lo ordenado en el ACUERDO DE RADICACIÓN Y REQUERIMIENTO dictado hoy, por el Magistrado José Oliveros Ruiz, integrante de este Tribunal Electoral, en el expediente al rubro indicado, siendo las dieciocho horas del día en que se actúa, el suscrito Actuario lo NOTIFICA A LAS PARTES Y DEMÁS INTERESADOS mediante cédula que se fija en los ESTRADOS de este Tribunal Electoral, anexando copia del acuerdo citado. DOY FE.----- D0§ !2 :-q NIÑO BELTRÁN TRIBUNAT TtECTtlRAt I}E VERACRUZ Tribunal Electoral de Veracruz JUIGIO PARA LA PROTECCIÓN DE LOS DERECHOS POL¡TICO- ELECTORALES DEL CIUDADANO. EXPEDIENTE: TEV-JDC-561201 8. ACTORES: ÁIVRRO ESTEBAN HERNÁNDEZ CAMARGO Y BLANCA ISABEL HERNÁNDEZ LARA. AUTORIDAD RESPONSABLE: JUNTA MUNICIPAL ELECTORAL DE TANTOYUCA, VERACRUZ. Xalapa, Veracruz, a ocho de abril de dos mil dieciocho. VISTO el acuerdo por el cual el Magistrado Presidente de este -

Proceso Electoral Interno 2020 - 2021

PROCESO ELECTORAL INTERNO 2020 - 2021 FECHA I DE FEBRERO DE 2021 ACUERDO COEEVERIAYTOS/PRCDNC/054 A#'pIDrr F I A f'UIO*1M f'DtAMI7AFfDA CI Cr'Tr'AI CTATAI re II Lti IVII.JIu1 t ULJ%JP IIL. I %IIS.I IP I P I IJI VERACRUZ, MEDIANTE EL CUAL SE DECLARA LA PROCEDENCIA DE REGISTRO DE PRECANDIDATURAS A LAS PLANILLAS ENCABEZADAS POR EL C. TEMISTOCLES GAMBOA MEZA, PARA EL AYUNTAMIENTO DE CAMARON DE TEJEDA, VERACRUZ, CON MOTIVO DEL PROCESO INTERNO DE SELECCION DE CANDIDATURAS A AYUNTAMIENTOS DEL ESTADO DE VERACRUZ, QUE REGISTRARA EL PARTIDO ACCION NACIONAL, DENTRO DEL PROCESO ELECTORAL LOCAL 2020-2021. EL PLENO DE LA COMISION ELECTORAL ESTATAL DEL PARTIDO ACCION NACIONAL EN VERACRUZ, EN RELACION CON EL PROCESO INTERNO DE SELECCION DE CANDIDATO A LAS ALCALDIAS ACAJETE, ACAYUCAN, ACTOPAN, AGUA DULCE, ALAMO TEMAPACHE, ALPATLAHUA, ALTO LUCERO, ALTOTONGA, ALVARADO, AMATLAN, ANGEL R. CABADA, ANTIGUA LA, ATOYAC, ATZACAN, ATZALAN, BANDERILLA, BEN ITO JUAREZ, BOCA DEL RIO, CAMERINO Z. MENDOZA, CAMARON DE TEJEDA, CARLOS A. CARRILLO, CARR!LLO PUERTO, CASTILLO DE TEAYO, CATEMACO, CAZONES DE HERRERA, CERRO AZUL, CHICONQUIACO, CHINAMPA DE GOROSTIZA, CHOAPAS LAS, CHOCAMAN, CHONTLA, CITLALTEPEC, COATEPEC, COATZACOALCOS, COMAPA, CORDOBA, COSAMALOAPAN, COSCOMATEPEC, COSOLEACAQUE, COTAXTLA, COXQUIHUI, CUICHAPA, CUITLAHUAC, EMILIANO ZAPATA, FILOMENO MATA, FORTIN, HIDALGOTITLAN, HUATUSCO, IXHUACAN DE LOS REYES, IXHUATLANCILLO, IXTACZOQUITLAN, JUAN RODRIGUEZ CLARA, JALTIPAN, JILOTEPEC, JOSE AZUETA, LANDERO Y COSS, LERDO DE TEJADA, MALTRATA, MANLIO FABIO ALTAMIRANO, -

Directorio Telefónico Subprocuradurías Y Ministerios Públicos Del Estado

Directorio Telefónico Subprocuradurías y Ministerios Públicos del Estado Actualización: 6 / 2013 Área responsable: Subprocuraduría de Supervisión y Control 01 SUBPROCURADURIA REGIONAL ZONA NORTE-TANTOYUCA 1 TITULAR Titular: LIC. TOMAS CRISTOBAL CRUZ Domicilio Cargo: EMILIANO ZAPATA No. ESQ. INDEPENDENCIA Teléfonos de Oficina: 8 37 14 54 Extensión: I P 3734 Colonia Lada: 783 8 37 14 55 Extensión: ADOLFO RUIZ CORTINES C.P. 92880 8 37 14 63 Fax 1: 8 37 14 54 Municipio Fax 2: TUXPAN, VER 2 AGENTE DEL MINISTERIO PÚBLICO AUXILIAR DEL C. SUBPROCURADOR Titular: LIC. RICARDO CARDENAS GONZALEZ Domicilio Cargo: CALLE GABINO BARREDA NO. 206 Teléfonos de Oficina: 8 93 43 08 Extensión: Colonia Lada: 789 8 93 43 22 Extensión: COL. EL JAGÜEY Fax 1: Municipio Fax 2: TANTOYUCA, VER Titular: LIC. RUBEN BARRADAS RODRIGUEZ Domicilio Cargo: Calle Gabino Barreda No. 206 Teléfonos de Oficina: 8 93 43 08 Extensión: Colonia Lada: 789 8 93 43 22 Extensión: El Juaguey Fax 1: Municipio Fax 2: Tantotuca, Ver. Titular: LIC. GUILLERMO AUGUSTO DIAZ SALAS Domicilio Cargo: CALLE GABINO BARREDA NO. 206 Teléfonos de Oficina: 8 93 43 08 Extensión: Colonia Lada: 789 8 93 43 22 Extensión: COL. EL JAGÜEY Fax 1: Municipio Fax 2: TANTOYUCA, VER 3 AGENTE DEL MINISTERIO PÚBLICO INVESTIGADOR Titular: LIC. GERARDO CARLOS CAMBEROS CORREA Domicilio Cargo: c. Benito Juárez S/N Teléfonos de Oficina: 2 57 03 43 Extensión: I P 3769 Colonia Lada: 846 Extensión: Plaza principal C. P. 92080 Fax 1: Municipio Fax 2: OZULAMA, VER Página 1 de 80 Directorio Telefónico Subprocuradurías y Ministerios Públicos del Estado Actualización: 6 / 2013 Área responsable: Subprocuraduría de Supervisión y Control Titular: LIC. -

Directorio De Comités Municipales Veracruz

DIRECTORIO DE COMITÉS MUNICIPALES ESTADO DE VERACRUZ MUNICIPIO DIRECCIÓN DEL TELÉFONO COMITÉ CAJETE CALLE AMERICAS S/N, 228-811-4054 DOMICILIO CONOCIDO, LA JOYA,VER ACATLÁN AV. LERDO N° 36, CENTRO, 228-119-6182 ACATLÁN, VER. ACAYUCAN CALLE RICARDO FLORES 924-112-4517 MAGÓN N° 16 NORTE, ACAYUCAN, VER. ACTOPAN DOMICILIO CONOCIDO, 296-100-8296 CENTRO, ACTOPAN, VER. ACULA CALLE MIGUEL HIDALGO S/N, 288-105-7029 CENTRO, ACULA, VER. ACULTZINGO CALLE UNIÓN N° 20, COL. 272-117-5119 CENTRO, ACULTZINGO, VER. AGUA DULCE ANDRÉS QUINTANA ROO N° 923-233-2301 12, COL. MAGISTERIAL, CP. 96660, AGUA DULCE, VER. ÁLAMO - TEMAPACHE CALLE DIAZ MIRÓN S/N, ESQ. 765-102-1614 INDEPENDENCIA, COL. CENTRO, CP 92730, ÁLAMO- TEMAPACHE, VER. ALPATLÁHUAC CALLE DE LA SOLEDAD S/N, 273-110-5505 CENTRO, CP. 94130, ALAPATLÁHUAC, VER. ALTO LUCERO DE GUTIÉRREZ CONGREGACIÓN VAINILLAS 228-108-3298 BARRIOS S/N, ALTO LUCERO, VER. ALTOTONGA CALLE MATAMOROS N° 10, 226-100-7046 COL. CENTRO, ALTOTONGA, VER. ALVARADO CALLE JOAQUÍN MARTÍNEZ N° 297-100-8262 720, COL. CENTRO AMATITLÁN DOMICILIO CONOCIDO, 921-178-0713 RANCHO NUEVO, AMATITLÁN, VER AMATLÁN DE LOS REYES CALLE 21 DE MAYO N° 11, 271-715-1111 COL. CENTRO, AMATLÁN DE LOS REYES, VER. ÁNGEL R. CABADA CALLE PRIMITIVO R. 283-104-6189 VALENCIA, ESQ. ÚRSULO GALVAN, ÁNGEL R. CABADA, VER. APAZAPAN CALLE ÚRSULO GALVÁN S/N, 279-108-1905 COL. CENTRO, COMINUDAD CHAHUAPAN, APAZAPAN, VER. AQUILA CALLE PRINCIPAL S/N, COL. 272-708-9859 CENTRO, CP. 94750, AQUILA, VER. ASTACINGA DOMICILIO CONOCIDO, 278-109-6134 CENTRO, CP. 94810, ASTACINGA, VER. ATLAHUILCO DOMICIOIO CONOCIDO, COL. -

Ley De Coordinacion Fiscal Para El Estado Y Los Municipios De Veracruz De Ignacio De La Llave

LEY DE COORDINACION FISCAL PARA EL ESTADO Y LOS MUNICIPIOS DE VERACRUZ DE IGNACIO DE LA LLAVE. ÚLTIMA REFORMA PUBLICADA EN LA GACETA OFICIAL: 14 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2011. Ley publicada en la Gaceta Oficial. Órgano del Gobierno del Estado de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, el jueves 30 de diciembre de 1999. Al margen un sello que dice: Estados Unidos Mexicanos.-Gobernador del Estado de Veracruz- Llave. Miguel Alemán Velazco, Gobernador Constitucional del Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz- Llave, a sus habitantes sabed: Que la H. Legislatura del Estado se ha servido dirigirme la siguiente Ley para su promulgación: Al margen un sello con el Escudo Nacional que dice: Estados Unidos Mexicanos.—Poder Legislativo.—Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz-Llave. "La Honorable Quincuagésima Octava Legislatura del Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz-Llave, en uso de la facultad que le confieren los artículos 68, fracción I de la Constitución Política Local; 44 de la Ley Orgánica del Poder Legislativo; 103 del Reglamento para el Gobierno Interior del Poder Legislativo y en nombre del pueblo, expide la siguiente: LEY NÚMERO 44 (REFORMADA SU DENOMINACION POR ARTICULO TERCERO TRANSITORIO DE LA CONSTITUCION POLITICA LOCAL, G.O. 18 DE MARZO DE 2003) DE COORDINACIÓN FISCAL PARA EL ESTADO Y LOS MUNICIPIOS DE VERACRUZ DE IGNACIO DE LA LLAVE CAPÍTULO I Disposiciones generales Artículo 1.La presente Ley establece y regula el Sistema Estatal de Coordinación Fiscal; y tiene por objeto: I. Establecer y regular los fondos para la distribución de las participaciones federales a los municipios; II. Establecer las reglas para la distribución de otros ingresos federales o estatales que se les transfieran a los municipios; III. -

DIRECTORIO DELEGACIONES CON FOTOS 12-11-16.Pdf

D I R E C T O R I O SUBDIRECCIÓN REGIONAL ZONA NORTE Blvd. Diaz Mirón S/N, Colonia Revolución, Pánuco, Ver. Tel.(228) 175 94 78 [email protected] Com. Gral. Jesús Alberto Hernández Domínguez Cel. 228 252 8110 REGIÓN I PANUCO D E L E G A D O S U B D E L E G A D O Pol. 3° Iván Gómez Hernández Cel. 846 109 10 87 Blvd. Díaz Mirón S/N, Colonia Revolución, Pánuco, Ver. Tel. 01 (846) 266 36 72 [email protected] Com. Gral. Antonio de Jesús Barrera Sobrevilla. Cel. 846 114 73 00 ENLACE ADMIN. Lic. Gumaro Valdés Ponce Cel. 846 104 98 98 ENLACE JURIDICO Lic. Martin Fuentes Rivera Cel. 228 176 44 98 CLAVE DE LA BASE Náhuatl GRUPOS MOVILES Huastecos REGIÓN II TUXPAN D E L E G A D O S U B D E L E G A D O Av. Ruiz Cortines #3, Col. R. Cortines, Tuxpan, Ver. Tel. 01 (783) 834 47 20 Cel. 783 83 409 39 01 (783) 834 09 39 [email protected] [email protected] Subinspector Felipe Martínez Reyes Policía Manuel Juárez Cel: 7831260347 Cel: 7831407003 ENLACE ADMIN. Teresa Espejel Pérez Cel. 783 115 57 20 ENLACE JURIDICO Lic. Carlos Ángel Navarro Mercado Cel. 228 116 28 39/ 228 196 19 61 CLAVE DE LA BASE Tamiahua GRUPOS MOVILES Tangos REGIÓN III BENITO JUÁREZ D E L E G A D O S U B D E L E G A D O Carr. Est. Benito Juárez – Chicontepec, Km 1, Benito Juárez, Ver.