Nigeria Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT of GRAVEL MINING in COMMUNITIES in OJI RIVER LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA of ENUGU STATE 1Officha, M.C., 2Okolie, A.O and 3Onwuemesi, F.E

GSJ: Volume 6, Issue 11, November 2018 ISSN 2320-9186 63 GSJ: Volume 6, Issue 11, November 2018, Online: ISSN 2320-9186 www.globalscientificjournal.com ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF GRAVEL MINING IN COMMUNITIES IN OJI RIVER LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF ENUGU STATE 1Officha, M.C., 2Okolie, A.O and 3Onwuemesi, F.E. 1Department of Architecture, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka 1Department of Architecture, Chuwkuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University Uli, Anambra State. 3Department of Environmental Management, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka. e-mail: [email protected]. Tell: +2348036938575 Abstract Increase in demand for sand and gravel mining has recently increased due to its demand in the construction of dams, roads, and building. The environmental impact of sand and gravel mining in three communities in Inyi town in Oji River Local Government Area of Enugu State has been studied using survey design. The aim of the study is to evaluate the impact of sand and gravel mining in the selected communities. The objectives of the study include; to investigate the method used by the miners in mining sand and gravel in the study area and to ascertain the impact of sand and gravel mining on the environment of the study area. Data for the study was collected through questionnaire, field observations and interview. 120 copies of well- structured questionnaire were distributed to the communities. Statistical tool use in the analysis of the data was simple percentage. From the study, sand and gravel mining in the selected communities has resulted to loss/reduction of farm lands and grazing lands, loss of vegetation, loss of biodiversity and economically important tress, destruction of landscape and beauty, confrontations/conflicts amongst communities, dust, water and soil pollution. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

WOMEN and Elecnons in NIGERIA: SOME EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE from the DECEMBER 1991 Elecnons in ENUGU STATE

64 UFAHAMU WOMEN AND ELEcnONS IN NIGERIA: SOME EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE FROM THE DECEMBER 1991 ELEcnONS IN ENUGU STATE Okechukwu lbeanu Introduction Long before "modem" (Western) feminism became fashionable, the "woman question" had occupied the minds of social thinkers. In fact, this question dates as far back as the Judeo-Christian (Biblical) notion that the subordinate position of women in society is divinely ordained. • Since then, there have also been a number of biological and pseudo-scientific explanations that attribute the socio-economic and, therefore, political subordination of women to the menfolk, to women's physiological and spiritual inferiority to men. Writing in the 19th century, well over 1,800 years A. D., both Marx and Engels situate the differential social and political positions occupied by the two sexes in the relations of production. These relations find their highest expression of inequality in the capitalist society (Engels, 1978). The subordination of women is an integral part of more general unequal social (class) relations. For Marx, "the degree of emancipation of women is the natural measure of general emancipation" (Vogel, 1979: 42). Most writings on the "woman problematique" have generically been influenced by the above perspectives. However, more recent works commonly emphasized culture and socialization in explaining the social position of women. The general idea is that most cultures discriminate against women by socializing them into subordinate roles (Baldridge, 1975). The patriarchal character of power and opportunity structures in most cultures set the basis for the social, political and economic subordination of women. In consequence, many societies socialize their members into believing that public life is not for the female gender. -

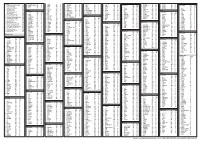

Niger Delta Budget Monitoring Group Mapping

CAPACITY BUILDING TRAINING ON COMMUNITY NEEDS ASSESSMENT & SHADOW BUDGETING NIGER DELTA BUDGET MONITORING GROUP MAPPING OF 2016 CAPITAL PROJECTS IN THE 2016 FGN BUDGET FOR ENUGU STATE (Kebetkache Training Group Work on Needs Assessment Working Document) DOCUMENT PREPARED BY NDEBUMOG HEADQUARTERS www.nigerdeltabudget.org ENUGU STATE FEDERAL MINISTRY OF EDUCATION UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION (UBE) COMMISSION S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. CONST. SEN. DIST. ZONE STATUS 1 Teaching and Learning 40,000,000 Enugu West South East New Materials in Selected Schools in Enugu West Senatorial District 2 Construction of a Block of 3 15,000,000 Udi Ezeagu/ Udi Enugu West South East New Classroom with VIP Office, Toilets and Furnishing at Community High School, Obioma, Udi LGA, Enugu State Total 55,000,000 FGGC ENUGU S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. CONST. SEN. DIST. ZONE STATUS 1 Construction of Road Network 34,264,125 Enugu- North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Enugu South 2 Construction of Storey 145,795,243 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Building of 18 Classroom, Enugu South Examination Hall, 2 No. Semi Detached Twin Buildings 3 Purchase of 1 Coastal Bus 13,000,000 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East Enugu South 4 Completion of an 8-Room 66,428,132 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Storey Building Girls Hostel Enugu South and Construction of a Storey Building of Prep Room and Furnishing 5 Construction of Perimeter 15,002,484 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Fencing Enugu South 6 Purchase of one Mercedes 18,656,000 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Water Tanker of 11,000 Litres Enugu South Capacity Total 293,145,984 FGGC LEJJA S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. -

NIGERIAN AGRICULTURAL JOURNAL ISSN: 0300-368X Volume 49 Number 2, October 2018

NIGERIAN AGRICULTURAL JOURNAL ISSN: 0300-368X Volume 49 Number 2, October 2018. Pp. 242-247 Available online at: http://www.ajol.info/index.php/naj EFFECT OF RURAL-URBAN MIGRATION ON RICE PRODUCTION IN ENUGU STATE, NIGERIA 1Apu, U., 1Okore, H.O., 2Nnamerenwa, G.C. and 1Gbede, O.A. 1Department of Rural Sociology and Extension; 2Department of Agricultural Economics, Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Umudike, Abia State Corresponding Authors’ email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This study assessed the effect of rural-urban migration on rice production in Enugu State, Nigeria. Multi-stage and Purposive sampling procedure was used to select 60 respondents which constituted the sample size of the study. Data were obtained through the use of a structured questionnaire. Descriptive statistics such as frequency counts and percentages, and inferential statistics such as correlation and z-test procedure were employed for analyses of data. Findings indicated that majority of the respondents (81.67%) were at their youthful age of 16 to 45 years old. The highest household size obtained was between 4 and 9 persons per household. Majority of the respondents in the study area (53.33%) were small scale farmers and had below 6 hectares of rice farm land. Poor living conditions, low influx of income and lack of employment were the most important reasons for rural-urban migration as confirmed by the respondents in Enugu State (65.00%). In the study area, 62.68% migrated to the urban areas. A larger proportion of the respondents (60.00%) indicated that between 4 and 9 household members participated in the rice production activities. -

6B JASR July 2016

JOURNAL OF APPLIED SCIENCES RESEARCH ISSN: 1819-544X Published BY AENSI Publication EISSN: 1816-157X http://www.aensiweb.com/ JASR 2016 January; 12(1): pages 49-54 Open Access Journal Poverty Alleviation and Women Cooperative Societies in Nsukka Local Government Area of Enugu State, Nigeria 1Eucharia Nchedo Aye, 2Theresa Olunwa Oforka, 3Victoria Lucy Eze, 4Chiedu Eseadi 1Department of Educational Foundations, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. 2Department of Educational Foundations, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. 3Department of Educational Foundations, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. 4Department of Educational Foundations, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. Received 12 January 2016; Accepted 26 January 2016; published 28 January 2016 Address For Correspondence: Eucharia Nchedo Aye, Department of Educational Foundations, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected]. Copyright © 2016 by authors and American-Eurasian Network for Scientific Information (AENSI Publication). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ABSTRACT Background: Women participation in cooperative societies has been receiving serious attention in developmental circles in recent time. Moreover, in different parts of the world, cooperatives and other collective forms of economic and social enterprise have shown themselves as being distinctly beneficial to improving women’s social and economic capacities. Objective: This study aimed at examining extent women partake in the poverty alleviation and women cooperative societies in Nsukka Local Government Area of Enugu State, Nigeria. Methodology: The study adopted a descriptive survey research design. All the 46 women cooperative societies and 1,380 members of the 46 registered women cooperative societies in Nsukka local government constitute the study. -

2016 South East Capital Budget Pullout

2016 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET Of the States in the SOUTH EAST Geo-Political Zone Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) 2016 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET of the States in the SOUTH EAST Geo-Political Zone Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) ii 2016 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET of the States in the SOUTH EAST Geo-Political Zone Compiled by VICTOR EMEJUIWE For Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) iii First Published in June 2016 By Citizens Wealth Platform C/o Centre for Social Justice 17 Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja Email: [email protected] Website: www.csj-ng.org Tel: 08055070909. Blog: csj-blog.org. Twitter:@censoj. Facebook: Centre for Social Justice, Nigeria iv Table of Contents Foreword vi Abia State 1 Anambra State 11 Ebonyi State 24 Enugu State 31 Imo State 50 v FOREWORD In accordance with the mandate of Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) to ensure that public resources are made to work and be of benefit to all, we present the federal capital budget pull-out of the states in the South East Geo-Political Zone of Nigeria for the financial year 2016. This has been our tradition since the last five years to provide capital budget information to Nigerians. The pull- out provides information on ministries, departments and agencies; name of projects, locations and the amount budgeted. By section 24 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigerian 1999 (as amended), it is the duty of every Nigerian to make positive and useful contributions to the advancement, progress and well-being of the community where she resides. -

ZONAL INTERVENTION PROJECTS Federal Goverment of Nigeria APPROPRIATION ACT

2014 APPROPRIATION ACT ZONAL INTERVENTION PROJECTS Federal Goverment of Nigeria APPROPRIATION ACT Federal Government of Nigeria 2014 APPROPRIATION ACT S/NO PROJECT TITLE AMOUNT AGENCY =N= 1 CONSTRUCTION OF ZING-YAKOKO-MONKIN ROAD, TARABA STATE 300,000,000 WORKS 2 CONSTRUCTION OF AJELE ROAD, ESAN SOUTH EAST LGA, EDO CENTRAL SENATORIAL 80,000,000 WORKS DISTRICT, EDO STATE 3 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE, OTADA, OTUKPO, BENUE STATE (ONGOING) 150,000,000 YOUTH 4 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE, OBI, BENUE STATE (ONGOING) 110,000,000 YOUTH 5 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE, AGATU, BENUE STATE (ONGOING) 110,000,000 YOUTH 6 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE-MPU,ANINRI LGA ENUGU STATE 70,000,000 YOUTH 7 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE-AWGU, ENUGU STATE 150,000,000 YOUTH 8 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE-ACHI,OJI RIVER ENUGU STATE 70,000,000 YOUTH 9 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE-NGWO UDI LGA ENUGU STATE 100,000,000 YOUTH 10 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE- IWOLLO, EZEAGU LGA, ENUGU STATE 100,000,000 YOUTH 11 YOUTH EMPOWERMENT PROGRAMME IN LAGOS WEST SENATORIAL DISTRICT, LAGOS STATE 250,000,000 YOUTH 12 COMPLETION OF YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE AT BADAGRY LGA, LAGOS 200,000,000 YOUTH 13 YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE IN IKOM, CROSS RIVER CENTRAL SENATORIAL DISTRICT, CROSS 34,000,000 YOUTH RIVER STATE (ON-GOING) 14 ELECTRIFICATION OF ALIFETI-OBA-IGA OLOGBECHE IN APA LGA, BENUE 25,000,000 REA 15 ELECTRIFICATION OF OJAGBAMA ADOKA, OTUKPO LGA, BENUE (NEW) 25,000,000 REA 16 POWER IMPROVEMENT AND PROCUREMENT AND INSTALLATION OF TRANSFORMERS IN 280,000,000 POWER OTUKPO LGA (NEW) 17 ELECTRIFICATION OF ZING—YAKOKO—MONKIN (ON-GOING) 100,000,000 POWER ADD100M 18 SUPPLY OF 10 NOS. -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

Sources of Information on Climate Change Among Crop Farmers in Enugu North Agricultural Zone, Nigeria

International Journal of Research in Agriculture and Forestry Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2015, PP 27-33 ISSN 2394-5907 (Print) & ISSN 2394-5915 (Online) Sources of Information on Climate Change among Crop Farmers in Enugu North Agricultural Zone, Nigeria Akinnagbe O.M1, Attamah C.O2, Igbokwe E.M2 1Department of Agricultural Extension and Communication Technology, Federal ,University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria) 2Department of Agricultural Extension, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria) ABSTRACT The study ascertained the sources of information on climate change among crop farmers in Enugu north agricultural zone of Enugu State, Nigeria. A multi-stage sampling technique was employed in selection of 120 crop farmers. Data for this study were collected through the use of structured interview schedule. Percentage, charts and mean statistic were used in data analysis and presentation of results. Findings revealed that majority of the respondents were female, married, and literate, with mean age of 38.98 years. The major sources of information on climate change were from neighbour (98.3%), fellow farmers (98.3%) and family members (98.3%). Among these sources, the major sources where crop farmers received information on climate change regularly were through fellow farmers (M=2.15) and neighbour (M=2.12). Since small scale crop farmers received and accessed climate change information from fellow farmers, neighbour and family members, there is need for extension agents working directly with contact farmers to improve on their service delivering since regular and timely information on farmers farm activities like the issue of climate change is of paramount important to farmers for enhance productivity Keywords: Information sources, climate change, crop farmers. -

Harnessing the Potentials of Caves and Rock-Shelters for Geotourism Development in Mmaku and Achi on Nsukka-Okigwe Cuesta, Nigeria

International Journal of Research in Tourism and Hospitality (IJRTH) Volume 4, Issue 2, 2018, PP 21-31 ISSN 2455-0043 http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2455-0043.0402003 www.arcjournals.org Harnessing the Potentials of Caves and Rock-Shelters for Geotourism Development in Mmaku and Achi on Nsukka-Okigwe Cuesta, Nigeria Chidinma C. Oguamanam1, Emeka E. Okonkwo 2* Department of Archaeology and Tourism, University of Nigeria, Nsukka *Corresponding Author: Emeka E. Okonkwo, Department of Archaeology and Tourism, University of Nigeria, Nsukka Abstract: Geology and landscape constitute a form of natural area tourism known as geotourism. Features of this form of tourism include cave, rock shelter, waterfall, among others. Geotourism attractions are visited because of their scenic geological formation, unmodified vegetation, water resources, among others; and are developed due to their valued contributions to community development, income generation and employment opportunities. Mmaku and Achi on Nsukka-Okigwe Cuesta are endowed with caves and rock shelters that can be harnessed for geotourism. This paper is aimed at examining the potentials of caves and rock shelters in the study areas with a view to harnessing them for geotourism. The study uses ethnographic research instruments to elicit useful information and data collected were analyzed descriptively. The study argues that Mmaku and Achi communities’ Standard of living can be enhanced if these natural resources are harnessed for geotourism. Keywords: Caves and Rock-shelters; Geotourism; Tourism potentials; Mmaku and Achi 1. INTRODUCTION The Nsukka-Okigwe cuesta trending north-south is seen by Afigbo (1976;1981) as the route of migration of the Igbo ancestors from the Benue confluence to Nsukka cuesta and this spread along the cuesta to other parts of Igbo land. -

Groundwater Analysis of Umumbo Area, in Orji River

International Journal of Geology, Earth & Environmental Sciences ISSN: 2277-2081 (Online) An Online International Journal Available at http://www.cibtech.org/jgee.htm 2013 Vol.3 (3) September-December, pp.193-196/Emmanuel Research Article GROUNDWATER ANALYSIS OF UMUMBO AREA, IN ORJI RIVER, ENUGU STATE *Nwabineli Emmanuel Department of Ceramic and Glass Technology, Akanuibiam Federal Polytechnic, Unwana, Ebonyi State *Author for Correspondence ABSTRACT The quantity and occurrence of groundwater depends on the geological characteristics of the host rock formation. These must be studied through a detailed hydro geophysical survey to know the Lithologic units where commercial quantity of water can be encountered during drilling and exploitation activities in order to benefit the end users. In the study both surface and subsurface geophysics methods were employed. The procedures used were Schlumberger array where the maximum AB/2 reached during the data acquisition varied from one place to another. The maximum spread was assumed to provide enough subsurface information considering the facts that the depth of penetration in a Schlumberger array ranges from between one third to one fourth of the current electrode separation. The Borehole drilled after the hydro geological survey by pacific geological Nigeria Company at Umumbo village in Oji River enabled the author the assessment of the groundwater’s potential and Hydro geological characteristics of the sandstone Aquifer of the Ajali formation of Anambra River Basin. The investigation shows that a saturated aquifer can be encountered at de depth of 100 meters. Key Words: Groundwater, Anambra River Basin, Ajali Formation, Geophysical Survey, Schlumberger Array INTRODUCTION Water is vital to all life on Earth.