The Application of Melodic Drumming Approaches in a Contemporary Small Jazz Ensemble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Vinyls-Collection.Com Page 1/222 - Total : 8629 Vinyls Au 05/10/2021 Collection "Artistes Divers Toutes Catã©Gorie

Collection "Artistes divers toutes catégorie. TOUT FORMATS." de yvinyl Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage !!! !!! LP GSL39 Etats Unis Amerique 10cc Windows In The Jungle LP MERL 28 Royaume-Uni 10cc The Original Soundtrack LP 9102 500 France 10cc Ten Out Of 10 LP 6359 048 France 10cc Look Hear? LP 6310 507 Allemagne 10cc Live And Let Live 2LP 6641 698 Royaume-Uni 10cc How Dare You! LP 9102.501 France 10cc Deceptive Bends LP 9102 502 France 10cc Bloody Tourists LP 9102 503 France 12°5 12°5 LP BAL 13015 France 13th Floor Elevators The Psychedelic Sounds LP LIKP 003 Inconnu 13th Floor Elevators Live LP LIKP 002 Inconnu 13th Floor Elevators Easter Everywhere LP IA 5 Etats Unis Amerique 18 Karat Gold All-bumm LP UAS 29 559 1 Allemagne 20/20 20/20 LP 83898 Pays-Bas 20th Century Steel Band Yellow Bird Is Dead LP UAS 29980 France 3 Hur-el Hürel Arsivi LP 002 Inconnu 38 Special Wild Eyed Southern Boys LP 64835 Pays-Bas 38 Special W.w. Rockin' Into The Night LP 64782 Pays-Bas 38 Special Tour De Force LP SP 4971 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Strength In Numbers LP SP 5115 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Special Forces LP 64888 Pays-Bas 38 Special Special Delivery LP SP-3165 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Rock & Roll Strategy LP SP 5218 Etats Unis Amerique 45s (the) 45s CD hag 009 Inconnu A Cid Symphony Ernie Fischbach And Charles Ew...3LP AK 090/3 Italie A Euphonius Wail A Euphonius Wail LP KS-3668 Etats Unis Amerique A Foot In Coldwater Or All Around Us LP 7E-1025 Etats Unis Amerique A's (the A's) The A's LP AB 4238 Etats Unis Amerique A.b. -

Kevin Ayers Joy of a Toy Mp3, Flac, Wma

Kevin Ayers Joy Of A Toy mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Joy Of A Toy Country: Japan Released: 2013 Style: Psychedelic Rock, Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1807 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1163 mb WMA version RAR size: 1563 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 194 Other Formats: VOC ASF XM AA DXD VOX AAC Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Joy Of A Toy Continued 2 Town Feeling 3 The Clarietta Rag 4 Girl On A Swing Song For Insane Times 5 Backing Band – The Soft Machine*Featuring – Hugh Hopper, Mike Ratledge Stop This Train (Again Doing It) 6 Drums – Rob Tait 7 Eleanor's Cake (Which Ate Her) 8 The Lady Rachel Oleh Oleh Bandu Bandong 9 Drums – Rob Tait 10 All This Crazy Gift Of Time Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Warner Music Japan Inc. Credits Arranged By, Piano – David Bedford Drums – Robert Wyatt (tracks: 1 to 5, 7, 8, 10) Producer – Kevin Ayers, Peter Jenner Notes Jewel Case 13-3-20 (03-6-9) (Y) Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 4943674177578 Other versions Title Category Artist Label Category Country Year (Format) Joy Of A Toy SHVL 763, 1E 062 Kevin Harvest, SHVL 763, 1E 062 (LP, Album, UK 1969 ○ 04210 Ayers Harvest ○ 04210 Gat) Joy Of A Toy Kevin MR-SSS 513 (LP, Album, Vinilisssimo MR-SSS 513 Spain 2012 Ayers RE, Gat) Joy Of A Toy Kevin SHVL 763 (LP, Album, Harvest SHVL 763 France 1970 Ayers Gat) Joy Of A Toy Kevin 07243-582776-2-3 (CD, Album, EMI, Harvest 07243-582776-2-3 Europe Unknown Ayers RE, RM) 4 Men With Joy Of A Toy Kevin Beards, 4 4M229, 4m229 (LP, Album, 4M229, 4m229 US 2012 Ayers Men With RE) Beards Related Music albums to Joy Of A Toy by Kevin Ayers Soft Machine - BBC Radio | 1967 - 1971 Kevin Ayers - Bananamour Kevin Ayers - The Confessions Of Dr. -

Sunday.Sept.06.Overnight 261 Songs, 14.2 Hours, 1.62 GB

Page 1 of 8 ...sunday.Sept.06.Overnight 261 songs, 14.2 hours, 1.62 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Go Now! 3:15 The Magnificent Moodies The Moody Blues 2 Waiting To Derail 3:55 Strangers Almanac Whiskeytown 3 Copperhead Road 4:34 Shut Up And Die Like An Aviator Steve Earle And The Dukes 4 Crazy To Love You 3:06 Old Ideas Leonard Cohen 5 Willow Bend-Julie 0:23 6 Donations 3 w/id Julie 0:24 KSZN Broadcast Clips Julie 7 Wheels Of Love 2:44 Anthology Emmylou Harris 8 California Sunset 2:57 Old Ways Neil Young 9 Soul of Man 4:30 Ready for Confetti Robert Earl Keen 10 Speaking In Tongues 4:34 Slant 6 Mind Greg Brown 11 Soap Making-Julie 0:23 12 Volunteer 1 w/ID- Tony 1:20 KSZN Broadcast Clips 13 Quittin' Time 3:55 State Of The Heart Mary Chapin Carpenter 14 Thank You 2:51 Bonnie Raitt Bonnie Raitt 15 Bootleg 3:02 Bayou Country (Limited Edition) Creedence Clearwater Revival 16 Man In Need 3:36 Shoot Out the Lights Richard & Linda Thompson 17 Semicolon Project-Frenaudo 0:44 18 Let Him Fly 3:08 Fly Dixie Chicks 19 A River for Him 5:07 Bluebird Emmylou Harris 20 Desperadoes Waiting For A Train 4:19 Other Voices, Too (A Trip Back To… Nanci Griffith 21 uw niles radio long w legal id 0:32 KSZN Broadcast Clips 22 Cold, Cold Heart 5:09 Timeless: Hank Williams Tribute Lucinda Williams 23 Why Do You Have to Torture Me? 2:37 Swingin' West Big Sandy & His Fly-Rite Boys 24 Madmax 3:32 Acoustic Swing David Grisman 25 Grand Canyon Trust-Terry 0:38 26 Volunteer 2 Julie 0:48 KSZN Broadcast Clips Julie 27 Happiness 3:55 So Long So Wrong Alison Krauss & Union Station -

Nas Profundezas Da Superfície Do Mate Com Angu

Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Ciências Sociais Departamento de Antropologia Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia Social Nas profundezas da Superfície do Mate com Angu: Projeções Antropológicas Sobre um Cinema da Baixada Fluminense de Tiago de Aragão Silva Brasília, 2011 Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Ciências Sociais Departamento de Antropologia Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia Social Nas Profundezas da Superfície do Mate com Angu: Projeções Antropológicas Sobre um Cinema da Baixada Fluminense Tiago de Aragão Silva Orientadora: Antonádia Monteiro Borges Dissertação apresentada no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia Social da Universidade de Brasília como um dos requisitos para obtenção do título de mestre. BANCA EXAMINADORA: Profª. Antonádia Monteiro Borges (DAN/UnB - Presidente) Profª. Dácia Ibiapina da Silva (FAC/UnB) Profª. Luciana Hartmann (CEN/IdA/UnB) SUPLENTE Prof. Guilherme José da Silva e Sá (DAN/UnB) À Emília e ao Mate com Angu. Agradecimentos Pelo encantamento, companheirismo, disposição e carinho, ao Mate com Angu, em especial a Slow Dabf, Samitri, Sabrina, Rosita, Rafael Mazza, Prestor, Paulo Mainhard, Muriel, Márcio Bertoni, Manu Castilho, Luísa Godoy, Josinaldo, João Xavi, Igor Cabral, Igor Barradas, Heraldo HB, Cataldo, Fabíola Trinca, DMC, Carola, Bia e André. Essa dissertação só existe por causa de vocês e de nosso encontro. Abraços deliciosos. Pelo canto, amor e acolhimento em Brasília, Arlete Aragão. Pelo sentimento de família, mesmo longe, Cesar. Por acompanhar essa trajetória no Rio, MC, George e Marisa. Agradeço a sólida base do Departamento de Antropologia da UnB, Rosa, Adriana, Branca, Paulo, Cristiane e Fernando. À Antonádia, pela certeza que foi a melhor escolha para orientar a realização de mais uma etapa de minha trajetória acadêmica, meu carinho, respeito e admiração. -

American Jazz Museum

AMERICAN JAZZ MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT | FISCAL YEAR 2014 OUR MISSION To celebrate and exhibit the experience of jazz as an original American art form through performance, exhibitions, education, and research at one of the country’s jazz crossroads: 18th & Vine. OUR VISION To become a premier destination that will expand the in!uence and knowledge of jazz throughout greater Kansas City and the world. OUR HISTORY Many years ago, 18th & Vine buzzed with the culture and commerce of Kansas City’s African-American community. The infectious energy of the people gave life to a new kind of music… and the music gave it right back to the people. Over the years the area languished, but the music and the musicians became legends! In 1989, the City of Kansas City, Missouri committed $26 million to a revitalization of 18th & Vine, led by the visionary and tireless efforts of then City Councilman and now Congressman Emanuel Cleaver II (former Kansas City Mayor.) By 1997, the city had a vibrant new complex housing the Kansas City Jazz Museum and the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, as well as the Horace M. Peterson III Visitor Center, with a newly refurbished Gem Theater across the street. Soon after, the Museum and its board and staff determined that the Kansas City Jazz Museum’s name should be changed to the American Jazz Museum to re!ect that the museum is the only museum in the world that is totally devoted to America’s true classical music -- jazz. The American Jazz Museum continues to ful"ll its mission by serving as a good caretaker of its collections and artifacts, as well as managing the Blue Room jazz club, the Gem Theater, the Changing Gallery, and the public spaces of the Museums at 18th & Vine. -

Eddie Who? - Eddie Harris Amerikansk Tenorsaxofonist, Født 20.10.1934 I Chicago, IL, D

Eddie Who? - Eddie Harris Amerikansk tenorsaxofonist, født 20.10.1934 i Chicago, IL, d. 5.11.1996 Sanger og pianist som barn i baptistkirker og spillede senere vibrafon og tenorsax. Debuterede som pianist med Gene Ammons før universitetsstudier i musik. Spillede med bl.a. Cedar Walton i 7. Army Symphony Orchestra. Fik i 1961 et stort hit og jazzens første guldplade med filmmelodien "Exodus", hvad der i de følgende år gav ham visse problemer med accept i jazzmiljøet. Udsendte 1965 The in Sound med bl.a. hans egen komposition Freedom Jazz Dance, som siden er indgået i jazzens standardrepertoire. Spillede fra 1966 elektrificeret saxofon og hybrider af sax og basun. Flirtede med rock på Eddie Harris In the UK (Atlantic 1969). Spillede 1969 på Montreux festivalen med Les McCann (Swiss Movement, Atlantic) og skrev 1969-71 musik til Bill Cosbys tv-shows. Spillede i 80'erne med bl.a. Tete Montoliu og Bo Stief (Steps Up, SteepleChase, 1981) og igen med Les McCann. Som sideman med bl.a. Jimmy Smith, Horace Silver, Horace Parlan og John Scofield (Hand Jive, Blue Note, 1993). Optrådte trods sygdom, så sent som maj 1996. Indspillede et stort antal plader for mange selskaber, fra 80'erne mest europæiske. Med udgangspunkt i bopmusikken udviklede Harris sine eksperimenter til en meget personlig stil med umiddelbart genkendelig, egenartet vokaliserende tone, fra 70'erne krydret med (ofte lange), humoristisk filosofisk/satiriske enetaler. Følte sig ofte underkendt som musiker og satiriserede over det i sin "Eddie Who". Kilde: Politikens Jazz Leksikon, 2003, red. Peter H. Larsen og Thorbjørn Sjøgren There's a guys (Chorus) You ought to know Eddie Harris .. -

PROGRAM NOTES Guided Tour

13/14 Season SEP-DEC Ted Kurland Associates Kurland Ted The New Gary Burton Quartet 70th Birthday Concert with Gary Burton Vibraphone Julian Lage Guitar Scott Colley Bass Antonio Sanchez Percussion PROGRAM There will be no intermission. Set list will be announced from stage. Sunday, October 6 at 7 PM Zellerbach Theatre The Annenberg Center's Jazz Series is funded in part by the Brownstein Jazz Fund and the Philadelphia Fund For Jazz Legacy & Innovation of The Philadelphia Foundation and Philadelphia Jazz Project: a project of the Painted Bride Art Center. Media support for the 13/14 Jazz Series provided by WRTI and City Paper. 10 | ABOUT THE ARTISTS Gary Burton (Vibraphone) Born in 1943 and raised in Indiana, Gary Burton taught himself to play the vibraphone. At the age of 17, Burton made his recording debut in Nashville with guitarists Hank Garland and Chet Atkins. Two years later, Burton left his studies at Berklee College of Music to join George Shearing and Stan Getz, with whom he worked from 1964 to 1966. As a member of Getz's quartet, Burton won Down Beat Magazine's “Talent Deserving of Wider Recognition” award in 1965. By the time he left Getz to form his own quartet in 1967, Burton had recorded three solo albums. Borrowing rhythms and sonorities from rock music, while maintaining jazz's emphasis on improvisation and harmonic complexity, Burton's first quartet attracted large audiences from both sides of the jazz-rock spectrum. Such albums as Duster and Lofty Fake Anagram established Burton and his band as progenitors of the jazz fusion phenomenon. -

1 FLORIDA BANDMASTERS ASSOCIATION SOLO and ENSEMBLE LIST – PERCUSSION and PIANO Rev

1 FLORIDA BANDMASTERS ASSOCIATION SOLO AND ENSEMBLE LIST – PERCUSSION AND PIANO Rev. 2003 G COMPOSER/ARRANGER TITLE PUB R SIG FBA EVENT O CODE A LIT CODE O D P E BELWIN CLASSIC FESTIVAL SOLOS MALLET PERCUSSION VOL 1 (P 2-7 ANY 1) BEL 1 MA1001 MALLET SOLO BELWIN CLASSICAL FESTIVAL BOOK FOR MALLETS VOL.2 (P.2 - 8 ANY 1) BEL 1 MA1002 MALLET SOLO BELWIN CLASSIC FESTIVAL SOLOS MALLET PERCUSSION VOL 1 (P 8-15 ANY 1) BEL 2 MA2001 MALLET SOLO BELWIN CLASSICAL FESTIVAL BOOK FOR MALLETS VOL.2 (P.10 - 16 ANY 1) BEL 2 MA2002 MALLET SOLO GREIG / ROY EROTIK MMP 2 MA2003 MALLET SOLO RAMEAU / SCARMOLIN / MEISTER LA VILLAGEOISE LUD 2 MA2004 MALLET SOLO SIENNICKI TWO SHORT PIECES (1 MVT) LUD 2 MA2005 MALLET SOLO TCHAIKOWSKY / LEBON FOLK SONG (ALBUM FOR THE YOUNG) EMP 2 MA2006 MALLET SOLO BACH / MARTEAU / MEISTER ANDANTE CANTABILE LUD 3 MA3001 MALLET SOLO BARTOK/MIESTER EVENING IN THE COUNTRY LUD 3 MA3002 MALLET SOLO BEETHOVEN / NAGY / MEISTER TURKISH MARCH LUD 3 MA3003 MALLET SOLO BOCCHERENI EDWARDS MINUET (MARIMBA) RU 3 MA3004 MALLET SOLO BRAHMS / QUICK HUNGARIAN DANCE NO 5 (MARIMBA) RU 3 * MA3005 MALLET SOLO DONT / MEISTER BON VIVANT LUD 3 MA3006 MALLET SOLO DRIGO / ROY PIZZICATO MMP 3 MA3007 MALLET SOLO GABRIEL / MARIE / EDWARDS LA CINZUANTAINE (MARIMBA) RU 3 MA3008 MALLET SOLO GOUNOD / ROY FUNERAL MARCH OF A MARIONETTE MMP 3 MA3009 MALLET SOLO GREEN ARABIAN MINUTE DANCE (XYL) CF 3 MA3010 MALLET SOLO GREIG / ROY NORWEGIAN DANCE MMP 3 MA3011 MALLET SOLO HAYDN / BARNES GYPSY RONDO LUD 3 MA3012 MALLET SOLO HAYDN / NAGY / MEISTER MENUET LUD 3 MA3013 MALLET SOLO LECUONA / PETERSON MALAGUENA (XYL OR MAR) HL 3 * MA3014 MALLET SOLO LEONARD SOLOIST FOLIO FOR MARIMBA OR XYLOPHONE (P. -

Downloaded PDF File of the Original First-Edi- Pete Extracted More Music from the Song Form of the Chart That Adds Refreshing Contrast

DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

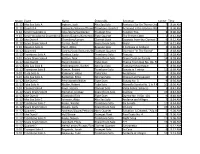

Grade Event Name Enteredas Selection

Grade Event Name EnteredAs Selection Center Time 11-12 Alto Sax Solo A Ingham, Josh Alto Sax Solo Fantaisie Sur Un Theme Original 7 8:00 AM 11-12 Quartet A GajewsKy/Johnson/Thomas/VidovicTrombone Quartet Achieved is the Glorious WorK 5 8:06 AM 9-10 Small Ensemble A Hess/Story/VanRoeKel Trumpet Trio Tandem Trio 8 8:06 AM 9-10 Small Woodwind Ensemble A Boten/GasKins/Kamencic/KiefferFlute Quartet The French Clock 2 8:12 AM 11-12 LiKe Duet A Chambera/Larson Clarinet Duet Excerpts from the Clarinet Concerto9 8:12 AM 11-12 Snare Drum Solo A Carrier, Brett Snare Drum Solo Shala' 15 8:12 AM 9-10 Bassoon Solo A Hunt, Abbie Bassoon Solo 3 Fantasia in G Major 4 8:18 AM 11-12 Quartet B Conrey/CooK/Richards/StovieTrumpet Quartet Overture "In The Forest" 5 8:18 AM 11-12 Trombone Solo A Benitez, Lesly Trombone Solo Toccata 11 8:18 AM 9-10 Snare Drum Solo A Battani, NicK Snare Drum Solo Drum CorpI on Parade 14 8:18 AM 11-12 LiKe Duet B Huynh/Kadoun Flute Duet Theme From Duo No, Op. 59 9 8:24 AM 11-12 Alto Sax Solo B Hollingsworth, Rachel Alto Sax Solo Fantaisie Mauresque 7 8:30 AM 11-12 Trombone Solo B Kaman, Robert Trombone Solo Sonata in F minor 11 8:30 AM 9-10 Flute Solo A Kamencic, Alena Flute Solo Andalouse 1 8:36 AM 9-10 Alto Sax Solo A Bartschat, EriKa Alto Sax Solo Chanson et Passepied 6 8:36 AM 11-12 LiKe Duet C Penningroth/WilKer Flute Duet Sonata No.