The Impacts of Leisure Travel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hording and Billboards in Cities a Major Source of Visual Pollution

www.ijcrt.org © 2018 IJCRT | Volume 6, Issue 1 March 2018 | ISSN: 2320-2882 HORDING AND BILLBOARDS IN CITIES A MAJOR SOURCE OF VISUAL POLLUTION. ROMANA AFREEN 1,JYOTHI.J 2,RUBINA ANJUM 3. 1. Assistant professor in Department of Zoology and principal Alsharay Women’s Degree College ,Kalaburagi. karnataka,india 2. Research Scholar Department of Zoology, Gulbarga University, Kalaburagi. Research Centre Bi Bi Roza Degree College For Women’s Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India. 3. Assistant lecturer in chemistry. Alsharay Women’s Degree College ,Kalaburagi.karnataka.india. ABSTRACT: Visual pollution is the term given to unattractive or unnatural visual elements of a vista, a landscape, or any other thing that a person might not want to look at. Commonly cited examples are houses, automobiles, traffic signs, road signs, highways, roadways, billboards, litter, graffiti, overhead power lines, utility, contrails, skywriting, buildings, weeds and advertisements. These are ually considered visual pollution when placed in a landscape or surrounding where the person seeing them things that they do not fit. For example big billboards n a countryside village or graffiti on an old eighteenth century house can be seen as visual pollution. KEY WORDS: Visual pollution, poisonous chemicals, heavy metals, toxic substances. INTRODUCTION: The word pollution implies a negative impact on our environment. When a reference is made to polluting the environment we commonly think of land, air and water pollution. The types of images we conger up are the dumping of chemicals into our environment, toxic smoke being released into the air, litter lining our streets and parks, poisonous chemicals following into our ponds and rivers, toxins and heavy metals penetrating our ground water supplies. -

Understanding Pollution: Visual Pollution Is More Than Just a Bad

Understanding Pollution: Visual Pollution Is More than Just a Bad View Pollution doesn’t always have to be about earth shattering issues that will determine the fate of the planet. Sometimes, pollution is about the little things that determine whether we have a good day or a bad day. I am speaking specifically of what is known as visual pollution. I remember as a kid walking out the backdoor of my house, and seeing nothing but woods as far as my little eyes could see. It was beautiful, and I have dozens if not hundreds of memories of exploring those woods with a wide eyed wonder. Then, when I was a teenager, I walked out my backdoor, and those woods were gone. They were replaced by construction sites as dozens of new homes were being built. Far be it from me to deny anyone a home, but I never had the same feeling of serenity walking out and seeing those construction sites, and later houses, as I did those woods. Now, you may be thinking “boohoo, cry me a river.” I understand, but visual pollution isn’t simply just a desire for an aesthetically pleasing view. The term visual pollution “encompasses different visually unattractive elements of a certain landscape. This type of pollution doesn't have to be necessarily connected to environmental damage, and is in fact more an aesthetic issue that can vary from one person to other.”i Visual pollution can encompass things from landfills to advertising billboards, telephone and power lines, street signs, graffiti, traffic lights, and really anything that someone might consider an eyesore.ii Visual pollution is also connected to most other forms of pollution. -

Cabinet – 16 July 2015

CITY & COUNTY OF SWANSEA CABINET – 16 JULY 2015 APPENDICES INDEX AGENDA 9.a EU Rural Development Plan 2014-2020 'LEADER' Programme Grant 1 - 63 Acceptance. 11.a Annual 2014/15 Performance Monitoring Report. 64 - 190 12.a Sustainable Swansea - Fit for the future: Delivery Programme Review. 191 - 264 LEADER 2014-2020 CITY AND COUNTY OF SWANSEA RURAL LOCAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 2014- 2020 SEPTEMBER 2014 VERSION: 1 Page 1 of 52 Page 1 DATE: SEPTEMBER 2014 Please use Arial Size 12 throughout the document for consistency This template is intended as a guide. Please ensure that you complete this in conjunction with the full LEADER 2014-2020 Local Development Strategy Guidance document issued in June 2014 NAME OF LAG AND CONTACT DETAILS Name of Swansea Rural Development Partnership Local Action Group Administrative Body Primary Contact Name Paul Relf Tel 01792 636858 E-mail [email protected] Address Place Directorate Economic Regeneration & Planning City and County of Swansea Oystermouth Road Swansea SA1 3SN Administrative Body Secondary Contact Name Elliott Williams Tel 01792 635677 E-mail [email protected] Address Place Directorate Economic Regeneration & Planning City and County of Swansea Oystermouth Road Swansea SA1 3SN LOCAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY IMPLEMENTATION TIMESCALES Proposed Start Date 1 January 2015 (no earlier than 1 January 2015) End Date (no later than 31 December 2021) 31 December 2021 Page 2 of 52 Page 2 Suggested word limits have been provided for each section as a guide however these are not prescriptive SECTION 1 – STRATEGIC FIT Description Explain how the Local Development Strategy (LDS) fits with EU strategies, policies and programmes and the extent to which it aligns with the Focus Areas of the Wales Rural Development Programme (2014-2020) and the five LEADER themes as appropriate to the context of the LDS. -

Air Pollution Awareness in the Scope of the Community Service Practices Course: an Interdisciplinary Study

International Electronic Journal of Environmental Education Vol.8, Issue 1, 2018, 35-63 RESEARCH ARTICLE Air Pollution Awareness in the Scope of the Community Service Practices Course: An Interdisciplinary Study Funda AYDIN-GÜÇ* Giresun University, Giresun, TURKEY Müge AYGÜN** Giresun University, Giresun, TURKEY Derya CEYLAN* Giresun University, Giresun, TURKEY Seda ÇAVUŞ-GÜNGÖREN* Çanakkale On Sekiz Mart University, Çanakkale, TURKEY Ümmü Gülsüm DURUKAN* Giresun University, Giresun, TURKEY Yasemin HACIOĞLU* Giresun University, Giresun, TURKEY Ayşe Dilek YEKELER* Giresun University, Giresun, TURKEY To cite this article: Aydın-Güç, F., Aygün, M., Ceylan, D., Çavuş-Güngören, S., Durukan, Ü., G., Hacıoğlu, Y., & Yekeler, A., D. Air pollution awareness in the scope of the community service practices course: An interdisciplinary study. International Electronic Journal of Environmental Education, 8(1), 35-63 Abstract The aim of this study is to determine the effect of the interdisciplinary (the disciplines of Turkish, Social Science, Natural Sciences, Mathematics and Public Administration) activities performed in the scope of the Community Service Practices Course on the air pollution awareness (APW). This study has been performed as a multiple case study. Participants consisted of 32 pre-service elementary school teachers and 122 elementary school students enrolled in a 4th grade. Data were collected using the Air Pollution Awareness Questionnaire, Know-Want-Learn forms and interviews. Content analysis was used for analysis of data. The APW of participants have increased. It has been determined that the pre-service elementary school teachers have evaluated the implementation as being generally successful. Also it has been seen that the implementation has served different purposes out of the study aim for the pre-service elementary school teachers like providing teaching experience and how to teach the interdisciplinary subjects. -

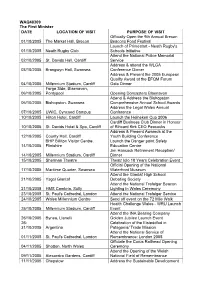

WAQ48309 the First Minister DATE LOCATION OF

WAQ48309 The First Minister DATE LOCATION OF VISIT PURPOSE OF VISIT Officially Open the 9th Annual Brecon 01/10/2005 The Market Hall, Brecon Beacons Food Festival Launch of Primestart - Neath Rugby's 01/10/2005 Neath Rugby Club Schools Initiative Attend the National Police Memorial 02/10/2005 St. Davids Hall, Cardiff Service Address & attend the WLGA 03/10/2005 Brangwyn Hall, Swansea Conference Dinner Address & Present the 2005 European Quality Award at the EFQM Forum 04/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Gala Dinner Forge Side, Blaenavon, 06/10/2005 Pontypool Opening Doncasters Blaenavon Attend & Address the Bishopston 06/10/2005 Bishopston, Swansea Comprehensive Annual School Awards Address the Legal Wales Annual 07/10/2005 UWIC, Cyncoed Campus Conference 10/10/2005 Hilton Hotel, Cardiff Launch the Heineken Cup 2006 Cardiff Business Club Dinner in Honour 10/10/2005 St. Davids Hotel & Spa, Cardiff of Rihcard Kirk CEO Peacocks Address & Present Awareds at the 12/10/2005 County Hall, Cardiff Youth Building Conference BHP Billiton Visitor Centre, Launch the Danger point Safety 14/10/2005 Flintshire Education Centre Jim Hancock Retirement Reception/ 14/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Dinner 15/10/2005 Sherman Theatre Theatr Iolo 18 Years Celebration Event Official Opening of the National 17/10/2005 Maritime Quarter, Swansea Waterfront Museum Attend the Glantaf High School 21/10/2005 Ysgol Glantaf Debating Society Attend the National Trafalgar Beacon 21/10/2005 HMS Cambria, Sully Lighting in Wales Ceremony 23/10/2005 St. Paul's Cathedral, London Attend the National Trafalgar Service 24/10/2005 Wales Millennium Centre Send off event on the 72 Mile Walk Health Challenge Wales - WRU Launch 25/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Event Attend the INA Bearing Company 26/10/2005 Bynea, Llanelli Golden Jubilee Launch Event 26- Celebration of the Eisteddfod in 31/10/2005 Argentina Patagonia/ Trade Mission Attend the National Service of 01/11/2005 St. -

Pollution Is Defi Ned As Contaminants That Enter the Environment Pollutionpollution and Cause Damage Or Negative Changes

DOWNLOADABLE EXTRAS Ecology and the Environment 1 Making a Food Web Cut around the following name and pictures to build your own food web. Remember to layout a draft food web fi rst before gluing them permanently onto page 14 of your workbook. magmama gots deadedeeaaddl leaveaavveses pospoposo sumsus huhu beeeete le ratraatat funfuunngusgugusus kekerkerereruereru gecgge ko deaddeeaadda animninimimalsaalllss eareaara thwthhwh ormoorrms rotrorotottinttiininggw woodoodd mirmim o ttototaraararaa sslslalaaterteterers frofrfrog kiwkiwiwi wetw a Pollution is defi ned as contaminants that enter the environment PollutionPollution and cause damage or negative changes. Pollution can include chemicals such as oil, CFC’s, radioactive compounds or even energy like heat, light and sound. These contaminants are referred to as pollutants. There are many different kinds of pollution and three keyy ones are outlined below. Air Pollution This is when particulates or other harmful materials are released into the atmosphere. Our atmosphere is vital to the survival of all living things and is what makes our planet habitable. It has been estimated that seven million people die each year from air pollution related illness and disease. As well as death, air pollution also causes breathing diffi culties, heart disease, asthma, stroke and lung cancer. Air pollution also affects plants and animal growth, and can destroy habitats through the production of acid rain. Smog is a combination of soot, smoke and sulfur dioxide mainly from vehicles, burning fossil fuels and factory fumes. Not only this but it can form ground level ozone which is quite toxic to all living organisms. This combination of emissions creates a thick smoky fog that covers cities and contributes to the major health problems stated above. -

A Hybrid Tool for Visual Pollution Assessment in Urban Environments

sustainability Article A Hybrid Tool for Visual Pollution Assessment in Urban Environments Khydija Wakil 1,*, Malik Asghar Naeem 1, Ghulam Abbas Anjum 2, Abdul Waheed 1, Muhammad Jamaluddin Thaheem 3 , Muhammad Qadeer ul Hussnain 1 and Raheel Nawaz 4 1 Department of Urban & Regional Planning, National University of Science & Technology (NUST), Islamabad H-12, Pakistan; [email protected] (M.A.N.); [email protected] (A.W.); [email protected] (M.Q.H.) 2 Department of City & Regional Planning, University of Engineering & Technology (UET), Lahore 54000, Pakistan; [email protected] 3 Department of Construction Engineering, National University of Science & Technology (NUST), Islamabad H-12, Pakistan; [email protected] 4 Department of Operations, Technology, Events and Hospitality Management, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester M13 9PL, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +92-333-626-0791 Received: 3 January 2019; Accepted: 24 February 2019; Published: 12 April 2019 Abstract: With increasing focus on more nuanced aspects of quality of life, the phenomenon of urban visual pollution has been progressively gaining attention from researchers and policy makers, especially in the developed world. However, the subjectivity and complexity of assessing visual pollution in urban settings remain a challenge, especially given the lack of robust and reliable methods for quantification of visual pollution. This paper presents a novel systematic approach for the development of a robust Visual Pollution Assessment (VPA) tool. A key feature of our methodology is explicit and systematic incorporation of expert and public opinion for listing and ranking Visual Pollution Objects (VPOs). -

Measuring Visual Pollution with Tangential View Landscape Metrics

land Article Chaos in Motion: Measuring Visual Pollution with Tangential View Landscape Metrics Szymon Chmielewski Department of Grassland and Landscape Studies, University of Life Sciences in Lublin, Akademicka 15 St., 20-950 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] Received: 21 November 2020; Accepted: 10 December 2020; Published: 12 December 2020 Abstract: Visual pollution (VP) in the form of outdoor advertisements (OA) is a threat to landscape physiognomy. Despite their proven usefulness in landscape aesthetic studies, landscape metrics have not yet been applied to address the phenomenon of VP. To fill this knowledge gap, a methodological framework for the measurement of VP using tangential view landscape metrics is proposed, which is accompanied by statistically significant proofs. Raster products derived from aerial laser scanning data were used to characterize two study areas with different topographic conditions in the city of Lublin, East Poland. The visibility of the cityscape in motion was simulated through viewshed measurements taken at equal intervals in the forwards and backwards directions along pedestrian walkways. The scrutinized tangential view landscape metrics (visible area, maximum visible distance, skyline, Shannon depth, view depth line) was the object of a two-fold interpretation wherein the spatial occurrence of VP as well as its impacts on the visual landscape character (VLC) were examined. The visible area metrics were found to be highly sensitive VP indicators. The maximum visible distance metrics provided evidence for the destructive effect of OA on view corridors. The Shannon depth and depth line metrics were not found to be statistically significant indicators of VP.Results from directional viewshed modelling indicate that distortion in the analyzed cityscape physiognomy depends on the view direction. -

(Lds) May 2020 Delivering the Rdp Leader Programme in Swansea

RDP LEADER 2014-2020 SWANSEA COUNCIL LOCAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY (LDS) MAY 2020 DELIVERING THE RDP LEADER PROGRAMME IN SWANSEA Location: Lliw Reservoir, Mawr Ward NAME OF LOCAL ACTION GROUP (LAG) AND CONTACT DETAILS Name of Swansea Rural Development Partnership LAG Administrative Body Primary Contact (also known as LAG Official) Name Victoria Thomson Tel 077962 75087 E-mail [email protected] Address Planning & City Regeneration Swansea Council Oystermouth Road Swansea SA1 3SN Administrative Body Secondary Contact Name Clare James Tel 07980 939678 E-mail [email protected] Address Planning & City Regeneration Swansea Council Oystermouth Road Swansea SA1 3SN LOCAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY IMPLEMENTATION TIMESCALES Start Date 1 July 2015 End Date 30 June 2023 Preface: Please note this is the fourth version of the LDS. Two earlier editions, dated September 2014 and March 2016, covered in detail the setting up of the programme and the various administrative systems. A further, third, November 2017 version retained some of this information but also more accurately reflected the, then, current position with the programme and delivery. This fourth edition brings us up-to-date and reflects the resolution by the Swansea Rural Development Partnership to align this strategy with the One Planet framework and approach. It was compiled by Helen Grey, External Funding Programme Officer. v4, May 2020. Copies of the previous LDS are available upon request from [email protected] Page 2 of 88 Table of Contents Foreword from Chair -

National Management Measures to Control Nonpoint Source Pollution from Urban Areas (November 2005, EPA-841-B-05-004)

This PDF file is an excerpt from the EPA guidance document entitled National Management Measures to Control Nonpoint Source Pollution from Urban Areas (November 2005, EPA-841-B-05-004). The full guidance can be downloaded from http://www.epa.gov/owow/nps/urbanmm/index.html. National Management Measures to Control Nonpoint Source Pollution from Urban Areas Management Measure 9: Pollution Prevention November 2005 Management Measure 9: Pollution Prevention MANAGEMENT MEASURE 9 POLLUTION PREVENTION 9.1 Management Measure Implement pollution prevention and education programs to reduce nonpoint source pollutants generated from the following activities: — The improper storage, use, and disposal of household chemicals, including automobile fluids, pesticides, paints, solvents, etc.; — Lawn and garden activities, including the improper application and disposal of lawn and garden care products, and the disposal of leaves and yard trimmings; — Turf management on golf courses, parks, and recreational areas; — Commercial activities, including parking lots and gas stations; — Improper disposal of pet wastes; and — Activities that generate trash. 9.2 Management Measure Description and Selection 9.2.1 Description This management measure is intended to prevent or reduce nonpoint source pollutant loadings generated from a variety of activities within urban areas. Everyday activities of citizens, municipal employees, and businesses have the potential to contribute to nonpoint source pollutant loadings. These activities include improper use and disposal of household chemicals, lawn and garden maintenance, turf grass management, operation and maintenance of diesel and gasoline vehicles, illicit discharges to urban runoff conveyances, commercial activities, and improper pet waste disposal. Reducing pollutant generation can decrease adverse water quality impacts from these sources. -

Soil Factors Influencing Eutrophication. in Soilguide. a Handbook for Understanding and Managing Agricultural Soils

Research Library Bulletins 4000 - Research Publications 2001 Soil factors influencing eutrophication. In Soilguide. A handbook for understanding and managing agricultural soils. (ed. Geoff Moore) David Weaver Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia Robert Summers Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/bulletins Part of the Agriculture Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Soil Science Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Weaver, D, and Summers, R. (2001), Soil factors influencing eutrophication. In Soilguide. A handbook for understanding and managing agricultural soils. (ed. Geoff Moore). Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Western Australia, Perth. Bulletin. This bulletin is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Publications at Research Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletins 4000 - by an authorized administrator of Research Library. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Soil Interpretation Manual Chapter 7: Sustainable soil management 7.3 Soil factors influencing eutrophication David Weaver and Rob Summers Eutrophication is essentially the nutrient enrichment of waterways leading to algal growth. It must be controlled to maintain sustainable agricultural systems and the main mechanisms of control are stabilising catchment processes and reducing nutrient output. Eutrophication can be defined as 'the nutrient enrichment of waters which results in the stimulation of an array of symptomatic changes, among which increased production of algae and macrophytes, deterioration of water quality and other symptomatic changes, are found to be undesirable and interfere with water uses' (OECD 1982). The word eutrophic is a Greek word that means 'well fed'. -

Environmental Pollution and Ways to Reduce Contamination with Use of Environmental Engineering Techniques in Metropolises of Developing Countries Pedram Saremi

International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology, 5(3) May-Jun, 2020 | Available: https://ijeab.com/ Environmental Pollution and ways to Reduce Contamination with use of Environmental Engineering Techniques in Metropolises of Developing Countries Pedram Saremi Master Student in Transportation Engineering Civil Engineering Dept. Sapienza University, Rome, Italy Abstract— Environmental pollution comes from a variety of sources. With the advancement of human civilization and the development of technology and population growth, now the world is facing a problem called pollution in air and land, which threatens the lives of the world's inhabitants. One of the current crises is environmental pollution, which mostly is considered to be the result of the technology, industrial and agricultural development expansion. If there is no control over the Progressive and exponential growth of this phenomenon, we will face an environmental catastrophe and disaster. In a simple definition, environmental pollution is any change in the Features of environmental components, i.e. water, soil, air, etc., so that it is impossible to use them optimally and endangers the lives of living organisms directly or indirectly. Access to healthy and adequate food, drinking water and clean air is the most obvious right of all humans, and the production and provision of these needs for citizens is an inherent duty of all governments. On the other hand, preserving the environment along with agricultural and industrial production activities is very important. The issue of environmental pollution and the creation of a sustainable environment is the main concern of all humans on earth. Fortunately, with the use of biotechnology and the available capabilities in nature, the Environmental damage rate can be minimized.