Karachi's Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manora Field Notes Naiza Khan

MANORA FIELD NOTES NAIZA KHAN PAVILION OF PAKISTAN CURATED BY ZAHRA KHAN MANORA FIELD NOTES NAIZA KHAN PAVILION OF PAKISTAN CURATED BY ZAHRA KHAN w CONTENTS FOREWORD – Jamal Shah 8 INTRODUCTION – Asma Rashid Khan 10 ESSAYS MANORA FIELD NOTES – Zahra Khan 15 NAIZA KHAN’S ENGAGEMENT WITH MANORA – Iftikhar Dadi 21 HUNDREDS OF BIRDS KILLED – Emilia Terracciano 27 THE TIDE MARKS A SHIFTING BOUNDARY – Aamir R. Mufti 33 MAP-MAKING PROCESS MAP-MAKING: SLOW AND FAST TECHNOLOGIES – Naiza Khan, Patrick Harvey and Arsalan Nasir 44 CONVERSATIONS WITH THE ARTIST – Naiza Khan 56 MANORA FIELD NOTES, PAVILION OF PAKISTAN 73 BIOGRAPHIES & CREDITS 125 bridge to cross the distance between ideas and artistic production, which need to be FOREWORD exchanged between artists around the world. The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of Pakistan, under its former minister Mr Fawad Chaudhry was very supportive of granting approval for the idea of this undertaking. The Pavilion of Pakistan thus garnered a great deal of attention and support from the art community as well as the entire country. Pakistan’s participation in this prestigious international art event has provided a global audience with an unforgettable introduction to Pakistani art. I congratulate Zahra Khan, for her commitment and hard work, and Naiza Khan, for being the first significant Pakistani artist to represent the country, along with everyone who played a part in this initiative’s success. I particularly thank Asma Rashid Khan, Director of Foundation Art Divvy, for partnering with the project, in addition to all our generous sponsors for their valuable support in the execution of our first-ever national pavilion. -

Central-Karachi

Central-Karachi 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Total Budget Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 1-Kalyana 408130186 GBELS - Elementary Elementary Boys 20,253 4,051 16,202 4,051 4,051 16,202 64,808 16,202 81,010 2 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130163 GBLSS - 11-G NEW KARACHI Middle Boys 24,147 4,829 19,318 4,829 4,829 19,318 77,271 19,318 96,589 3 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130167 GBLSS - MEHDI Middle Boys 11,758 2,352 9,406 2,352 2,352 9,406 37,625 9,406 47,031 4 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130176 GBELS - MATHODIST Elementary Boys 20,492 4,098 12,295 8,197 4,098 16,394 65,576 16,394 81,970 5 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 6-Hakim Ahsan 408130205 GBELS - PIXY DALE 2 Registred as a Seconda Elementary Girls 61,338 12,268 49,070 12,268 12,268 49,070 196,281 49,070 245,351 6 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 9-Khameeso Goth 408130174 GBLSS - KHAMISO GOTH Middle Mixed 6,962 1,392 5,569 1,392 1,392 5,569 22,278 5,569 27,847 7 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 10-Mustafa Colony 408130160 GBLSS - FARZANA Middle Boys 11,678 2,336 9,342 2,336 2,336 9,342 37,369 9,342 46,711 8 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 10-Mustafa Colony 408130166 GBLSS - 5/J Middle Boys 28,064 5,613 16,838 11,226 5,613 22,451 89,804 22,451 112,256 9 Central Karachi New Karachi -

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of Non CNIC Shareholders Final Dividend for the Year Ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of non CNIC shareholders Final Dividend For the year ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT_NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2 510007 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. 3 510008 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND KARACHI-74000. 4 510009 164 MR. MOHD. RAFIQ 1269 C/O TAJ TRADING CO. O.T. 8/81, KAGZI BAZAR KARACHI. 5 510010 169 MISS NUZHAT 1610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI 6 510011 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 KARACHI 7 510012 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD KARACHI 8 510015 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR KARACHI 9 510017 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI 10 510019 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 11 510020 300 MR. RAHIM 1269 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA BAZAR KARACHI 12 510021 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1610 A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL KARACHI 13 510022 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. -

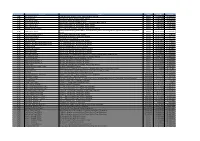

List of Branches Operational on Saturdays

List of branches operational on Saturdays City Branch Name Branch Address Ahmed Pur East Ahmedpur East 22, Dera Nawab Road, Adjacent Civil Hospital, Ahmed Pur. Arifwala Arifwala 173-D Thana Bazar Arifwala.Multan Bahawalnagar Bahawalnagar Shop # 02 Ghalla Mandi ,Bahawalnagar Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 2 - Rehman Society, Noor Mahal Road, Bahawalpur. Bhalwal Bhalwal 131-A, Liaqat Shaheed Road, Burewala Burewala 95-C, Multan Road, Burewala Chakwal Chakwal FBL-Talha gang road, opposite Alliace travel, chakwal Cheshtian Cheshtian 143 B - Block Main Bazar Cheshtian Chichawatni Chichawatni G.T Road Chichawatni Daska Daska Plot No.3,4 & 5,Muslim Market ,Gujranwala,Daska Depalpur Depalpur Shop # 1& 2, Gillani Heights,Madina Chowk,Depalpur Dera Ghazi Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Block 18, Pakistan Plaza,Hospital Chowk, Mazari Wala, Jampur Road ,Dera Ghazi Khan Dina Dina 1880- Al-Bilal Plaza, GT Road, Dina Dudial Dudial Hussain Shopping Centre, Main Bazar Branch, Dudial, Azad Kashmir. Faisalabad Liaquat Road Faisalabad P-III, Liaqat Road Gujar Khan Gujar Khan Faysal Bank Limited, B-111, 215-D, WARD 5, G.T. ROAD, Gujar Khan Gujranwala Gujranwala Zia Plaza, G.T. Road, Gujranwala. Gujrat Gujrat Nobel Furniture Plaza, G.T Road, Gujrat. Haroonabad Haroonabad 25/C Grain Market Haroonabad Distt Bahawalnager Hasilpur Hasilpur 16-D Baldia Road, Hasilpur Hyderabad Hyderabad Plot # 339,Main Bohra Bazar Saddar (Hyderabad) Islamabad F-11 Markaz Plot # 14, Markaz F-11, Sector F-11, Islamabad Islamabad Blue Area Blue Area, Islamabad Branch 78-W, Roshan Center, Jinnah Avenue, Blue Area ,Islamabad Jhang Jhang P-10/1/A, Katcheryi Road,Near Session Chowk,Saddar Jhang Jhelum Jehlum 225/226, Kohinoor Bank Square Old G.T. -

The Making of a ?Colony? in Karachi and the Politics of Regularisation

South AsSouth Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal Gazdar, Haris and Bux Mallah, Hussain (2012) ‘The Making of a ‘Colony’ in Karachi and the Politics of Regularisation’, South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, Thematic Issue Nb. 5, Rethinking Urban Democracy. URL : http://samaj.revues.org/index3248.html. To quote a passage, use paragraph (§). The Making of a ‘Colony’ in Karachi and the Politics of Regularisation Haris Gazdar and Hussain Bux Mallah Abstract. Around half of Karachi’s population resides in localities that started life as unplanned settlements, which acquired different levels of security from eviction. This paper examines the relationship between demand-making by unplanned settlements and urban political process. It interprets the gradual transformation of a cluster originally on the geographic and social periphery of the city into a regularised colony through the lens of collective action. The diverse roles of migration, mobilisation, and collective identity which we find in individual stories and community histories, capture a range of processes and experiences within Karachi’s wide margin. The politics of regularisation thus offers a critical perspective on the dynamics of urban democracy. Gazdar, Haris and Bux Mallah, Hussain (2012) ‘The Making of a ‘Colony’ in Karachi and the Politics of Regularisation’, South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, Thematic Issue Nb. 5, Rethinking Urban Democracy. URL : http://samaj.revues.org/index3248.htlm. To quote a passage, use paragraph (§). Introduction: Unplanned settlements and demand-making [1] While informality, particularly with respect to housing and land use, has a persuasive case as an epistemology for, rather than an aberration of, urban planning (Roy 2005), demand- making by unplanned settlements and not only by their individual inhabitants may have a similar claim with respect to urban political processes (Peattie & Aldrete-Haas 1981). -

December 2013 405 Al Baraka Bank (Pakistan) Ltd

Appendix IV Scheduled Banks’ Islamic Banking Branches in Pakistan As on 31st December 2013 Al Baraka Bank -Lakhani Centre, I.I.Chundrigar Road Vehari -Nishat Lane No.4, Phase-VI, D.H.A. (Pakistan) Ltd. (108) -Phase-II, D.H.A. -Provincial Trade Centre, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Askari Bank Ltd. (38) Main University Road Abbottabad -S.I.T.E. Area, Abbottabad Arifwala Chillas Attock Khanewal Faisalabad Badin Gujranwala Bahawalnagar Lahore (16) Hyderabad Bahawalpur -Bank Square Market, Model Town Islamabad Burewala -Block Y, Phase-III, L.C.C.H.S Taxila D.G.Khan -M.M. Alam Road, Gulberg-III, D.I.Khan -Main Boulevard, Allama Iqbal Town Gujrat (2) Daska -Mcleod Road -Opposite UBL, Bhimber Road Fateh Jang -Phase-II, Commercial Area, D.H.A. -Near Municipal Model School, Circular Gojra -Race Course Road, Shadman, Road Jehlum -Block R-1, Johar Town Karachi (8) Kasur -Cavalry Ground -Abdullah Haroon Road Khanpur -Circular Road -Qazi Usman Road, near Lal Masjid Kotri -Civic Centre, Barkat Market, New -Block-L, North Nazimabad Minngora Garden Town -Estate Avenue, S.I.T.E. Okara -Faisal Town -Jami Commercial, Phase-VII Sheikhupura -Hali Road, Gulberg-II -Mehran Hights, KDA Scheme-V -Kabeer Street, Urdu Bazar -CP & Barar Cooperative Housing Faisalabad (2) -Phase-III, D.H.A. Society, Dhoraji -Chiniot Bazar, near Clock Tower -Shadman Colony 1, -KDA Scheme No. 24, Gulshan-e-Iqbal -Faisal Lane, Civil Line Larkana Kohat Jhang Mansehra Lahore (7) Mardan -Faisal Town, Peco Road Gujranwala (2) Mirpur (AK) -M.A. Johar Town, -Anwar Industrial Complex, G.T Road Mirpurkhas -Block Y, Phase-III, D.H.A. -

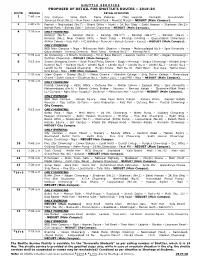

Shuttle Route

SHUTTLE SERVICES PROPOSED OF DETAIL FOR SHUTTLE’S ROUTES – 2019-20 ROUTE TIMINGS DETAIL OF ROUTES 1 7:40 a.m City Campus – Jama Cloth – Radio Pakistan – 7Day Hospital – Numaish – Gurumandir – Jamshed Road (No.3) – New Town – Askari Park – Mumtaz Manzil – NEDUET (Main Campus). 2 7:40 a.m Paposh – Nazimabad (No.7) – Board Office – Hydri – 2K Bus Stop – Sakhi Hassan – Shadman (No.2)– Namak Bank – Sohrab Goth – Gulshan Chowrangi – NEDUET (Main Campus). 4 7:20 a.m ONLY MORNING: Korangi (No.5) – Korangi (No.4) – Korangi (No.31/2) – Korangi (No.21/2) – Korangi (No.2) – Korangi (No.1, Near Chakra Goth) – Nasir Jump – Korangi Crossing – Qayyumabad Chowrangi – Akhtar Colony – Kala Pull – FTC Building – Nursery – Baloch Colony – Karsaz – NEDUET (Main Campus). ONLY EVENING: NED Main Campus – Nipa – Millennium Mall– Stadium – Karsaz – Mehmoodabad No.6 – Iqra University – Qayyumabad – Korangi Crossing – Nasir Jump – Korangi No.21/2 – Korangi No.5. 5 7:45 a.m 4K Chowrangi – 2 Minute Chowrangi – 5C-4 (Bara Market) – Saleem Centre – U.P Mor – Nagan Chowrangi – Gulshan Chowrangi – NEDUET (Main Campus). 6 7:15 a.m Shama Shopping Centre – Shah Faisal Police Station – Bagh-e-Korangi – Singer Chowrangi – Khaddi Stop – Korangi No.5 – Korangi No.6 – Landhi No.6 – Landhi No.5 – Landhi No.4 – Landhi No.3 – Landhi No.1 – Landhi No.89 – Dawood Chowrangi – Murghi Khana – Malir No.15 – Malir Hault – Star Gate – Natha Khan – Drig Road – Nipa – NED Main Campus. 7 7:35 a.m Islam Chowk – Orangi (No.5) – Metro Cinema – Abdullah College – Ship Owner College – Qalandarya Chowk – Sakhi Hassan – Shadman No.1 – Buffer Zone – Fazal Mill – Nipa – NEDUET (Main Campus). -

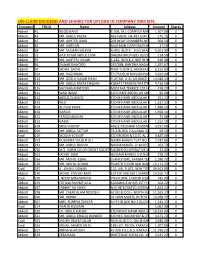

Un-Claim Dividend and Shares for Upload in Company Web Site

UN-CLAIM DIVIDEND AND SHARES FOR UPLOAD IN COMPANY WEB SITE. Company FOLIO Name Address Amount Shares Abbott 41 BILQIS BANO C-306, M.L.COMPLEX MIRZA KHALEEJ1,507.00 BEG ROAD,0 PARSI COLONY KARACHI Abbott 43 MR. ABDUL RAZAK RUFI VIEW, JM-497,FLAT NO-103175.75 JIGGAR MOORADABADI0 ROAD NEAR ALLAMA IQBAL LIBRARY KARACHI-74800 Abbott 47 MR. AKHTER JAMIL 203 INSAF CHAMBERS NEAR PICTURE600.50 HOUSE0 M.A.JINNAH ROAD KARACHI Abbott 62 MR. HAROON RAHEMAN CORPORATION 26 COCHINWALA27.50 0 MARKET KARACHI Abbott 68 MR. SALMAN SALEEM A-450, BLOCK - 3 GULSHAN-E-IQBAL6,503.00 KARACHI.0 Abbott 72 HAJI TAYUB ABDUL LATIF DHEDHI BROTHERS 20/21 GORDHANDAS714.50 MARKET0 KARACHI Abbott 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD616.00 KARACHI0 Abbott 96 ZAINAB DAWOOD 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD1,397.67 KARACHI-190 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD KARACHI-19 Abbott 97 MOHD. SADIQ FIRST FLOOR 2, MADINA MANZIL6,155.83 RAMTLA ROAD0 ARAMBAG KARACHI Abbott 104 MR. RIAZUDDIN 7/173 DELHI MUSLIM HOUSING4,262.00 SOCIETY SHAHEED-E-MILLAT0 OFF SIRAJUDULLAH ROAD KARACHI. Abbott 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE14,040.44 APARTMENT0 PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. Abbott 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND4,716.50 KARACHI-74000.0 Abbott 135 SAYVARA KHATOON MUSTAFA TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND778.27 TOOSO0 SNACK BAR BAHADURABAD KARACHI. Abbott 141 WASI IMAM C/O HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA95.00 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE IST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHUDARABAD BRANCH BAHEDURABAD KARACHI Abbott 142 ABDUL QUDDOS C/O M HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA252.22 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHEDURABAD BRANCH BAHDURABAD KARACHI. -

Machine Type Location Address City Latitude Longitude ATM KHI

Machine Type Location Address City Latitude Longitude ATM KHI-Gulshan Iqbal B-148, Block-15, Gulshan-e Iqbal, University Road, Karachi Karachi 24.90571769 67.07942426 ATM KHI-Centenary 14-A, Block 6, PECHS, Sahara-e-Faisal, Karachi Karachi 24.86017029 67.06177533 ATM Hydri Branch ATM 1 D-15, Block H North Nazimabad, Karachi Karachi 24.94131856 67.04685688 ATM Karachi Main Branch Main Branch, opposite Habib Bank Plaza, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi Karachi 24.84926942 67.0050171 ATM WTC Clifton ATM 1 World Trade Center, 10, Khy-e-roomi, Clifton, Karachi Karachi 24.8269049 67.02859908 ATM WTC Clifton ATM 2 World Trade Center, 10, Khy-e-roomi, Clifton, Karachi Karachi 24.8269049 67.02859908 ATM Defence Branch, Shahbaz 12-C, LANE-2, KHAYABAN-E SHAHBAZ, Phase IV DHA, Karachi Karachi 24.80913553 67.06273288 SCB Operations Building, Ground Floor, Mohatta Building, Main I I Chundrigar Road, Opposite National Bank of Pakistan, ATM Saadiq Main Branch Karachi 24.85130169 67.02921867 Karachi ATM Gulsitan e Jauhar Branch 1 AlFiza Tower Gulistan-e-Jauhar, Karachi Karachi 24.91473807 67.12781936 ATM Garden Road Branch Kandawalla Building M.A Jinnah Road, Karachi Karachi 24.86556074 67.02477962 ATM Allama Iqbal Branch 72/S Block-2 PECHS, Karachi Karachi 24.87515103 67.05315471 ATM Hill Park Branch SNPA 16-A/1, Shaheed-e-Millat Road, Karachi Karachi 24.87408034 67.07406521 ATM Defence / Korangi Branch ATM1 Phase II 2 - C, Commercial Area - A Phase II, DHA, Karachi Karachi 24.84155621 67.05782712 ATM Defence / Korangi Branch ATM2 Phase II 2 - C, Commercial Area - A Phase II, DHA, Karachi Karachi 24.84155621 67.05782712 ATM FB Area Branch Plot No.C 10 Block No. -

Informal Land Controls, a Case of Karachi-Pakistan

Informal Land Controls, A Case of Karachi-Pakistan. This Thesis is Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Saeed Ud Din Ahmed School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University June 2016 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… i | P a g e STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………………………………………..………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed …………………………………………………………….…………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ……………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed …………………………………………………….……………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… ii | P a g e iii | P a g e Acknowledgement The fruition of this thesis, theoretically a solitary contribution, is indebted to many individuals and institutions for their kind contributions, guidance and support. NED University of Engineering and Technology, my alma mater and employer, for financing this study. -

The People of Karachi Demographic Characteristics

MONOGRAPHS IN THE ECONOMICS OF DEVELOPMENT No. 13 The People of Karachi Demographic Characteristics SULTAN S. HASHMI January 1965 PAKISTAN INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS Old Sind Assembly Building Bunder Road, Karachi (Pakistan) Price Rs. 5.00 PAKISTAN INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPME :ONOMICS Old Sind Assembly Building Bunder Road, Karachi-1 (Pakistan) The Institute carries out basic research studies on the economic problems of development in Pakistan and other Asian countries. It also provides training in economic analysis and research methodology for the professional members of its staff and for members of other organization concerned with development problems. Executive Board Mr. Said Hasan, H.Q.A. (Chairman) Mr. S. A. F. M. A. Sobhan Mr. G. S. Kehar, S.Q.A. (Member) (Member) Mr. M. L. Qureshi, S.Q.A. Mr. M. Raschid (Member) (Member) Mr. A. Rashid Ibrahim Mr. S. M. Sulaiman (Member-Treasurer) (Member) Professor A. F. A. Hussain Dr. Mahbubul Haq (Member) (Member) Mian Nazir Ahmad, T.Q.A. (Secretary) Director: Professor Nurul Islam Senior Research Adviser: Dr. Bruce Glassburner Research Advisers: Dr. W. Eric Gustafson; Dr. Ronald Soligo; Dr. Stephen R. Lewis, Jr.; Dr. Warren C. Robinson; Mr. William Seltzer. Senior Fellows: Dr. S. A. Abbas; Dr. M. Baqai; Dr. Mahbubul Haq; Professor T. Haq; Professor A. F. A. Hussain; Dr. R. H. Khandkar; Dr. Taufique Khan; Professor M. Rashid. Advisory Board Professor Max F. Millikan, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Professor Gunnar Myrdal, University of Stockholm. Professor E. A. G. Robinson, Cambridge University. MONOGRAPHS IN THE ECONOMICS OF DEVELOPMENT No. 13 The People of Karachi Demographic Characteristics SULTANS. -

Handbook for Good Clinical Laboratory Practices in Pakistan, Created by the Pakistan Academy of Sciences (PAS) in Cooperation with the U.S

In cooperation with The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine THE PAKISTAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES This activity was supported by the Pakistan Academy of Sciences, the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and the U.S. State Department. The Pakistan Academy of Sciences is solely responsible for this publication and the contents are the responsibility of the individual chapter authors. International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-578-46481-7 Additional copies of this report are available from the Pakistan Academy of Sciences. Copyright 2019 by the Pakistan Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Suggested Citation: Pakistan Academy of Sciences. 2019. Good Clinical Laboratory Practices in Pakistan. Islamabad, Pakistan. Printed by Shiuman Design & Print, Blue Area, Islamabad-Pakistan Price: $15; PKR 1500 Good Clinical Laboratory Practices in Pakistan Preface & Acknowledgements The Handbook for Good Clinical Laboratory Practices in Pakistan, created by the Pakistan Academy of Sciences (PAS) in cooperation with the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), is intended to serve as an informational guide for clinical laboratories in order to improve the health and wellbeing of people and animals in Pakistan. Promotion of laboratory best practices and communication between and among laboratories is the best way to enhance disease surveillance and to help establish the relationships that keep experts engaged with the international community of responsible practitioners working