Neil Longley the Sustained Competitive Advantage of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sun Devil Legends

SUN DEVIL LEGENDS over North Carolina. Local sports historians point to that game as the introduction of Arizona State Frank Kush football to the national scene. Five years later, the Sun Devils again capped an undefeated season by ASU Coach, 1958-1979 downing Nebraska, 17-14. The win gave ASU a No. In 1955, Hall of Fame coach Dan Devine hired 2 national ranking for the year, and ushered ASU Frank Kush as one of his assistants at Arizona into the elite of college football programs. State. It was his first coaching job. Just three years • The success of Arizona State University football later, Kush succeeded Devine as head coach. On under Frank Kush led to increased exposure for the December 12, 1995 he joined his mentor and friend university through national and regional television in the College Football Hall of Fame. appearances. Evidence of this can be traced to the Before he went on to become a top coach, Frank fact that Arizona State’s enrollment increased from Kush was an outstanding player. He was a guard, 10,000 in 1958 (Kush’s first season) to 37,122 playing both ways for Clarence “Biggie” Munn at in 1979 (Kush’s final season), an increase of over Michigan State. He was small for a guard; 5-9, 175, 300%. but he played big. State went 26-1 during Kush’s Recollections of Frank Kush: • One hundred twenty-eight ASU football student- college days and in 1952 he was named to the “The first three years that I was a head coach, athletes coached by Kush were drafted by teams in Look Magazine All-America team. -

PRO FOOTBALL HALL of FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2020-2021 Edition

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2020-2021 EDITIOn Quarterback Joe Namath - Hall of fame class of 1985 nEW YORK JETS Team History The history of the New York franchise in the American Football League is the story of two distinct organizations, the Titans and the Jets. Interlocking the two in continuity is the player personnel which went with the franchise in the ownership change from Harry Wismer to a five-man group headed by David “Sonny” Werblin in February 1963. The three-year reign of Wismer, who was granted a charter AFL franchise in 1959, was fraught with controversy. The on-the-field happenings of the Titans were often overlooked, even in victory, as Wismer moved from feud to feud with the thoughtlessness of one playing Russian roulette with all chambers loaded. In spite of it all, the Titans had reasonable success on the field but they were a box office disaster. Werblin’s group purchased the bankrupt franchise for $1,000,000, changed the team name to Jets and hired Weeb Ewbank as head coach. In 1964, the Jets moved from the antiquated Polo Grounds to newly- constructed Shea Stadium, where the Jets set an AFL attendance mark of 45,665 in the season opener against the Denver Broncos. Ewbank, who had enjoyed championship success with the Baltimore Colts in the 1950s, patiently began a building program that received a major transfusion on January 2, 1965 when Werblin signed Alabama quarterback Joe Namath to a rumored $400,000 contract. The signing of the highly-regarded Namath proved to be a major factor in the eventual end of the AFL-NFL pro football war of the 1960s. -

Wildcats in the Nba

WILDCATS IN THE NBA ADEBAYO, Bam – Miami Heat (2018-20) 03), Dallas Mavericks (2004), Atlanta KANTER, Enes - Utah Jazz (2012-15), ANDERSON, Derek – Cleveland Cavaliers Hawks (2005-06), Detroit Pistons Oklahoma City Thunder (2015-17), (1998-99), Los Angeles Clippers (2006) New York Knicks (2018-19), Portland (2000), San Antonio Spurs (2001), DIALLO, Hamidou – Oklahoma City Trail Blazers (2019), Boston Celtics Portland Trail Blazers (2002-05), Thunder (2019-20) (2020) Houston Rockets (2006), Miami Heat FEIGENBAUM, George – Baltimore KIDD-GILCHRIST, Michael - Charlotte (2006), Charlotte Bobcats (2007-08) Bulletts (1950), Milwaukee Hawks Hornets (2013-20), Dallas Mavericks AZUBUIKE, Kelenna -- Golden State (1953) (2020) Warriors (2007-10), New York Knicks FITCH, Gerald – Miami Heat (2006) KNIGHT, Brandon - Detroit Pistons (2011), Dallas Mavericks (2012) FLYNN, Mike – Indiana Pacers (1976-78) (2012-13), Milwaukee Bucks BARKER, Cliff – Indianapolis Olympians [ABA in 1976] (2014-15), Phoenix Suns (2015-18), (1950-52) FOX, De’Aaron – Sacramento Kings Houston Rockets (2019), Cleveland BEARD, Ralph – Indianapolis Olympians (2018-20) Cavaliers (2010-20), Detroit Pistons (1950-51) GABRIEL, Wenyen – Sacramento Kings (2020) BENNETT, Winston – Clevland Cavaliers (2019-20), Portland Trail Blazers KNOX, Kevin – New York Knicks (2019- (1990-92), Miami Heat (1992) (2020) 20) BIRD, Jerry – New York Knicks (1959) GILGEOUS-ALEXANDER, Shai – Los KRON, Tommy – St. Louis Hawks (1967), BLEDSOE, Eric – Los Angeles Clippers Angeles Clippers (2019), Oklahoma Seattle -

In Detroit, Where the Wheels Fell Off

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 19, No. 3 (1997) IN DETROIT, WHERE THE WHEELS FELL OFF by Mark Speck Detroit's pro football history is alive with the names of many wonderful heroes from a colorful past ... Potsy Clark, Buddy Parker, Bobby Layne, Alex Karras, Night Train Lane, Greg Landry, Altie Taylor, Joe Schmidt, Dick LeBeau, Bubba Wyche, Sheldon Joppru..... Bubba Wyche?! Sheldon Joppru?! Don't recognize them? Well, they too are a part of Detroit's history. Most of Detroit's history in professional football has been written by the N.F.L. Lions, one of the league's most fabled franchises. Their history, and the city's, is full of great teams, great stars, great plays and great games. For one year, however, the Lions shared Detroit with an ugly step-sister who wrote a chapter of the city's football history that most people would probably like to forget. That ugly stepsister was the Detroit Wheels. No, not Mitch Ryder's back-up band. These Detroit Wheels were a football team, or what passed for a football team that played in the World Football League in 1974. Wyche, brother of Sam Wyche, and Joppru were just two members of this Wheels' cast of characters that shared Detroit with the Lions. Actually, to set the record straight, they didn't really share Detroit with the Lions. The Wheels couldn't find a home in the city, so they had to play their home games in Ypsilanti, thirty-five miles from downtown Detroit, at Rynearson Stadium on the campus of Eastern Michigan University. -

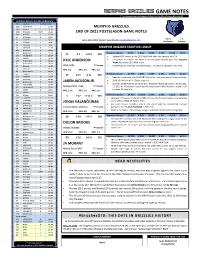

GAME NOTES for In-Game Notes and Updates, Follow Grizzlies PR on Twitter @Grizzliespr

GAME NOTES For in-game notes and updates, follow Grizzlies PR on Twitter @GrizzliesPR GRIZZLIES 2020-21 SCHEDULE/RESULTS Date Opponent Tip-Off/TV • Result 12/23 SAN ANTONIO L 119-131 MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES 12/26 ATLANTA L 112-122 12/28 @ Brooklyn W (OT) 116-111 END OF 2021 POSTSEASON GAME NOTES 12/30 @ Boston L 107-126 1/1 @ Charlotte W 108-93 38-34 1-4 1/3 LA LAKERS L 94-108 Game Notes/Stats Contact: Ross Wooden [email protected] Reg Season Playoffs 1/5 LA LAKERS L 92-94 1/7 CLEVELAND L 90-94 1/8 BROOKLYN W 115-110 MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES STARTING LINEUP 1/11 @ Cleveland W 101-91 1/13 @ Minnesota W 118-107 SF # 1 6-8 ¼ 230 Previous Game 4 PTS 2 REB 5 AST 2 STL 0 BLK 24:11 1/16 PHILADELPHIA W 106-104 Selected 30th overall in the 2015 NBA Draft after two seasons at UCLA. 1/18 PHOENIX W 108-104 First player to compile 10+ steals in any two-game playoff span since Dwyane 1/30 @ San Antonio W 129-112 KYLE ANDERSON 2/1 @ San Antonio W 133-102 Wade during the 2013 NBA Finals. th 2/2 @ Indiana L 116-134 UCLA / USA 7 Season Career-high 94 3PM this season (previous: 24 3PM in 67 games in 2019-20). 2/4 HOUSTON L 103-115 PPG: 8.4 RPG: 5.0 APG: 3.2 2/6 @ New Orleans L 109-118 2/8 TORONTO L 113-128 PF # 13 6-11 242 Previous Game 21 PTS 6 REB 1 AST 1 STL 0 BLK 26:01 2/10 CHARLOTTE W 130-114 Selected fourth overall in 2018 NBA Draft after freshman year at Michigan State. -

Former Panthers in The

FORMER PANTHERS IN THE NFL EASTERN EARNS TITLE OF 'CRADLE OF COACHES' Tony Romo Dallas Cowboys IN THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE Quarterback From 2006-2008, Eastern Illinois University held the distinction of being the new ‘Cradle of Coaches’ in the National Football Romo was a free agent signee League with three alumni serving as head coaches in the NFL and with the Dallas Cowboys in 2003. four more former players serving as assistant coaches. He started his first game with In 2006 and 2007, EIU was matched with USC and San Diego the Cowboys in 2006 earning State as the only three universities with three current NFL head All-Pro honors in 2006 and 2007 coaches as alumni. In 2008 that number was trimmed down to after guiding the team to back-to- just USC and EIU having three head coaches. In 2010 EIU once back NFC playoff appearances again was the "NFL Cradle of Coaches" as Mike Shanahan took including an NFC East title in over as head coach of the Washington Redskins. 2007. He was also an All-Pro following the 2009 season. Former All-American quarterback Sean Payton, Class of 1987, became the newest member of the distinguished club when he was named head coach of the New Orleans Saints early in 2006. Sean Payton He was an All-American quarterback with Eastern from 1983-86, New Orleans Saints and threw for a school record 10,655 yards. He still holds 11 Head Coach single game, season and career passing records. In 2006 he was named the NFL Coach of the Year guiding the Saints to the NFC Payton, a former EIU All-American, Championship game. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. IDgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & HoweU Information Compaiy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 OUTSIDE THE LINES: THE AFRICAN AMERICAN STRUGGLE TO PARTICIPATE IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL, 1904-1962 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State U niversity By Charles Kenyatta Ross, B.A., M.A. -

THE HISTORY of SMU FOOTBALL 1910S on the Morning of Sept

OUTLOOK PLAYERS COACHES OPPONENTS REVIEW RECORDS HISTORY MEDIA THE HISTORY OF SMU FOOTBALL 1910s On the morning of Sept. 14, 1915, coach Ray Morrison held his first practice, thus marking the birth of the SMU football program. Morrison came to the school in June of 1915 when he became the coach of the University’s football, basketball, baseball and track teams, as well as an instructor of mathematics. A former All-Southern quarterback at Vanderbilt, Morrison immediately installed the passing game at SMU. A local sportswriter nicknamed the team “the Parsons” because the squad was composed primarily of theology students. SMU was a member of the Texas Intercollegiate Athletic Association, which ruled that neither graduate nor transfer students were eligible to play. Therefore, the first SMU team consisted entirely of freshmen. The Mustangs played their first game Oct. 10, 1915, dropping a 43-0 decision to TCU in Fort Worth. SMU bounced back in its next game, its first at home, to defeat Hendrix College, 13-2. Morrison came to be known as “the father of the forward pass” because of his use of the passing game on first and second downs instead of as a last resort. • During the 1915 season, the Mustangs posted a record of 2-5 and scored just three touchdowns while giving up 131 Ownby Stadium was built in 1926 points. SMU recorded the first shutout in school history with a 7-0 victory over Dallas University that year. • SMU finished the 1916 season 0-8-2 and suffered its worst 1920s 1930s loss ever, a 146-3 drubbing by Rice. -

Nba Legacy -- Dana Spread

2019-202018-19 • HISTORY NBA LEGACY -- DANA SPREAD 144 2019-20 • HISTORY THIS IS CAROLINA BASKETBALL 145 2019-20 • HISTORY NBA PIPELINE --- DANA SPREAD 146 2019-20 • HISTORY TAR HEELS IN THE NBA DRAFT 147 2019-20 • HISTORY BARNES 148 2019-20 • HISTORY BRADLEY 149 2019-20 • HISTORY BULLOCK 150 2019-20 • HISTORY VC 151 2019-20 • HISTORY ED DAVIS 152 2019-20 • HISTORY ellington 153 2019-20 • HISTORY FELTON 154 2019-20 • HISTORY DG 155 2019-20 • HISTORY henson (hicks?) 156 2019-20 • HISTORY JJACKSON 157 2019-20 • HISTORY CAM JOHNSON 158 2019-20 • HISTORY NASSIR 159 2019-20 • HISTORY THEO 160 2019-20 • HISTORY COBY WHITE 161 2019-20 • HISTORY MARVIN WILLIAMS 162 2019-20 • HISTORY ALL-TIME PRO ROSTER TAR HEELS WITH NBA CHAMPIONSHIP RINGS Name Affiliation Season Team Billy Cunningham (1) Player 1966-67 Philadelphia 76ers Charles Scott (1) Player 1975-76 Boston Celtics Mitch Kupchak Player 1977-78 Washington Bullets Tommy LaGarde (1) Player 1978-79 Seattle SuperSonics Mitch Kupchak Player 1981-82 Los Angeles Lakers Bob McAdoo Player 1981-82 Los Angeles Lakers Bobby Jones (1) Player 1982-83 Philadelphia 76ers Mitch Kupchak (3) Player 1984-85 Los Angeles Lakers Bob McAdoo (2) Player 1984-85 Los Angeles Lakers James Worthy Player 1984-85 Los Angeles Lakers James Worthy Player 1986-87 Los Angeles Lakers James Worthy (3) Player 1987-88 Los Angeles Lakers Michael Jordan Player 1990-91 Chicago Bulls Scott Williams Player 1990-91 Chicago Bulls Michael Jordan Player 1991-92 Chicago Bulls Scott Williams Player 1991-92 Chicago Bulls Michael Jordan Player -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Mythical Framing Messages in ESPN.Com

Running Head: SETTING A SUPER AGENDA 1 Setting a Super Agenda: A Rhetorical Analysis of Mythical Framing Messages in ESPN.com’s Coverage of the NBA Finals A thesis submitted to Southern Utah University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Professional Communication June 2016 By Hayden Coombs SETTING A SUPER AGENDA 2 SETTING A SUPER AGENDA 3 Approval Page We certify that we have read and viewed this project and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Professional Communication. Capstone Committee ________________________________________________ Kevin Stein, Ph.D., chair _______________________________________________ Arthur Challis, Ed.D. _______________________________________________ Jon Smith, Ph.D. SETTING A SUPER AGENDA 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my beautiful wife Summer for being such an amazing mother to our children. The knowledge that our girls were receiving the absolute best care while I was out of the house so much these past 16 months enabled me to focus on my studies and reach my potential as a graduate student. I love you so freaking much! And to my girls, Avery Sue and Reese Julia, thank you for continually giving me a reason to be better than I actually am. You girls will never understand how much I love you. To my parents and siblings, thank you for inspiring me to continue my education and pursue a career in academia. I know it’s not a report card, but at least now you have something tangible to prove that I actually earned my masters. -

Would Fans Watch Football in the Spring?

12 THE USFL • The Rebel League the NFL Didn’t Respect but Feared 12 SPRING KICKOFF Would Fans Watch Football in the Spring? The league was the brainchild of Louisiana antique and art dealer David Dixon. Dixon remembers when 25,000 people would come out to watch Tulane have a springtime scrimmage back in the 1930s… “My God, why can’t we play games in Arizona and Denver. Washington drew by Dixon to sit the spring?” Dixon said, in an interview with 38,000 spectators, while Los Angeles and in on the owner’s Greg Garber from ESPN.com. “I mean, Birmingham drew more than 30,000. meetings, said, “I LSU still draws numbers like that to this The total attendance for opening week- thought the league day. If Princeton and Rutgers had played end was more than 230,000; an aver- would succeed be- that first [intercollegiate football] game in age of 39,170 per game. The national TV cause I had such the spring instead of the fall [Nov. 6, 1869], ratings for all games played was 14.2, with trust in David and that’s when we’d be playing football today. a 33 percent share. The USFL kicked-off to a the owners trusted “Football is such a powerful, power- great start. him. This wasn’t like ful piece of entertainment,” he continued. Originally, owners settled on a $1.8 mil- the World Football Mora “To me, it made a lot of sense to start a lion dollar salary cap per team; $1.3 million League which was new league.” dollars was allotted to sign 38 players and a an agent-created nightmare.” Teams were placed in 12 locations: Phil- 10-player developmental squad; $500,000 Many experts thought the spring league adelphia, Boston, New Jersey, Washing- was allotted to sign two “star” players. -

Fighting Illini Football History

HISTORY FIGHTING ILLINI HISTORY ILLINOIS NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP TEAMS 1914 Possibly the most dominant team in Illinois football history was the 1914 squad. The squad was only coach Robert Zuppke’s second at Illinois and would be the first of four national championship teams he would lead in his 29 years at Illinois. The Fighting Illini defense shut out four of its seven opponents, yielding only 22 points the entire 1914 season, and the averaged up an incredible 32 points per game, in cluding a 51-0 shellacking of Indiana on Oct. 10. This team was so good that no one scored a point against them until Oct. 31, the fifth game of the seven-game season. The closest game of the year, two weeks later, wasn’t very close at all, a 21-7 home decision over Chicago. Leading the way for Zuppke’s troops was right halfback Bart Macomber. He led the team in scoring. Left guard Ralph Chapman was named to Walter Camp’s first-team All-America squad, while left halfback Harold Pogue, the team’s second-leading scorer, was named to Camp’s second team. 1919 The 1919 team was the only one of Zuppke’s national cham pi on ship squads to lose a game. Wisconsin managed to de feat the Fighting Illini in Urbana in the third game of the season, 14-10, to tem porarily knock Illinois out of the conference lead. However, Zuppke’s men came back from the Wisconsin defeat with three consecutive wins to set up a showdown with the Buckeyes at Ohio Stadium on Nov.