Hellenistic Jewelry & the Commoditization of Elite Greek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ibycus Pmgf 287: Love and Disgrace Ἔρος Αὖτέ Με Κυανέοισιν Ὑπὸ Βλεφάροις Τακέρ' Ὄµ

IBYCUS PMGF 287: LOVE AND DISGRACE Ἔρος αὖτέ µε κυανέοισιν ὑπὸ βλεφάροις τακέρ’ ὄµµασι δερκόµενος κηλήµασι παντοδαποῖς ἐς ἄπει- ρα δίκτυα Κύπριδος ἐσβάλλει· 5 ἦ µὰν τροµέω νιν ἐπερχόµενον, ὥστε φερέζυγος ἵππος ἀεθλοφόρος ποτὶ γήρᾳ ἀέκων σὺν ὄχεσφι θοοῖς ἐς ἅµιλλαν ἔβα. Judging from the source which has preserved this fragment for us and from its overall structure, which I will analyze below, I believe that these lines of Ibycus constitute in all probability a complete poem1. This provides us the opportunity for a thorough interpretation and evaluation, an opportu- nity which has not, in my opinion, been adequately exploited by scholars so far. The intricacy and dexterity of Ibycus’ poetic art in this particular speci- men of his work has gone largely unnoticed. As will be seen by the ensuing analysis, there is not even a single word in these seven verses which has a superfluous or merely ornamental function; on the contrary, it is carefully chosen, put and invested with a particular significance that contributes ef- fectively to the production of the implicit meaning that the poet imparts to his creation. And this meaning mostly concerns the unavoidable danger of facing disgrace in one’s efforts of erotic conquest. The first remark to be made is that Ibycus’ poem is comprised by two distinct images, which are however implicitly linked2; an initial connection is established by the correlation between the phrase Ἔρος αὖτέ µε and the adjective φερέζυγος: the subjugation of the horse, which comes to represent the poetic persona that Ibycus here adopts, denotes precisely that the speaker is constantly under the influence of Eros, that he finds himself repeatedly falling in love. -

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

Kretan Cult and Customs, Especially in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods: a Religious, Social, and Political Study

i Kretan cult and customs, especially in the Classical and Hellenistic periods: a religious, social, and political study Thesis submitted for degree of MPhil Carolyn Schofield University College London ii Declaration I, Carolyn Schofield, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been acknowledged in the thesis. iii Abstract Ancient Krete perceived itself, and was perceived from outside, as rather different from the rest of Greece, particularly with respect to religion, social structure, and laws. The purpose of the thesis is to explore the bases for these perceptions and their accuracy. Krete’s self-perception is examined in the light of the account of Diodoros Siculus (Book 5, 64-80, allegedly based on Kretan sources), backed up by inscriptions and archaeology, while outside perceptions are derived mainly from other literary sources, including, inter alia, Homer, Strabo, Plato and Aristotle, Herodotos and Polybios; in both cases making reference also to the fragments and testimonia of ancient historians of Krete. While the main cult-epithets of Zeus on Krete – Diktaios, associated with pre-Greek inhabitants of eastern Krete, Idatas, associated with Dorian settlers, and Kretagenes, the symbol of the Hellenistic koinon - are almost unique to the island, those of Apollo are not, but there is good reason to believe that both Delphinios and Pythios originated on Krete, and evidence too that the Eleusinian Mysteries and Orphic and Dionysiac rites had much in common with early Kretan practice. The early institutionalization of pederasty, and the abduction of boys described by Ephoros, are unique to Krete, but the latter is distinct from rites of initiation to manhood, which continued later on Krete than elsewhere, and were associated with different gods. -

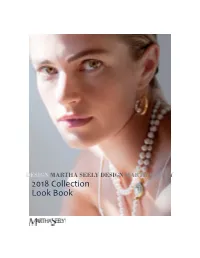

2018 Collection Look Book Martha Seely Design Is a Small Design Studio That Creates One-Of-A-Kind and Custom Crafted Fine Production Jewelry

DESIGN MARTHA SEELY DESIGN MARTHA SEELY 2018 Collection Look Book Martha Seely Design is a small design studio that creates one-of-a-kind and custom crafted fine production jewelry. The studio is pleased to customize the jewelry for individual retailers, using various karats and colors of precious metals, as well as providing selective choices of gemstones. INSPIRO Abstract Orbiting Spirals marthaseely.com 978-287-4628 When universes come together…. Simple, abstract spirals that move freely surrounding lustrous pearls and gemstones Ceres Spiral Earrings with diamonds Articulating 2-tone necklace Ceres Spiral Earrings not to scale with sapphires some items enlarged to show detail. The Delicate Collection – fresh and youthful Delicate Spiral Necklaces with 1,3 or 5 spirals with diamonds Delicate Dangle Earrings with Rutilated quartz not to scale some items enlarged to show detail. Delicate Spiral Link Bracelet Transition Unexpected twists, curves, with the fashion-forward use of pearls marthaseely.com 978-287-4628 Unexpected twists, curves, with the fashion-forward use of pearls Artisanal, hand-fabricated pieces that epitomize that time of year when the world is transforming and metamorphosis takes place. Transition Bangle in sterling silver with a white Akoya Pearl not to scale some items enlarged to show detail. Transition Bangle – 2-tone With gold and sterling silver And a riveted white Akoya pearl Transition Hoop Earrings in sterling silver With riveted Akoya pearl. CIRRUS This simple spiral expression is an updated and renewed classic design with pearls and diamonds. marthaseely.com 978-287-4628 Updated, Renewed Classic Designs Tahitian Pearl Post Earrings with Diamonds Tahitian Pearl Pendant with Diamonds Seed Pearl Necklaces in white and grey with 12mm white freshwater pearl. -

Athens & Ancient Greece

##99668811 ATHENS & ANCIENT GREECE NEW DIMENSION/QUESTAR, 2001 Grade Levels: 9-13+ 30 minutes DESCRIPTION Recalls the historical significance of Athens, using modern technology to re-create the Acropolis and Parthenon theaters, the Agora, and other features. Briefly reviews its history, famous citizens, contributions, a typical day, and industries. ACADEMIC STANDARDS Subject Area: World History - Era 3 – Classical Traditions, Major Religions, and Giant Empires, 1000 BCE – 300 CE Standard: Understands how Aegean civilization emerged and how interrelations developed among peoples of the Eastern Mediterranean and Southwest Asia from 600 to 200 BCE • Benchmark: Understands the major cultural elements of Greek society (e.g., the major characteristics of Hellenic sculpture, architecture, and pottery and how they reflected or influenced social values and culture; characteristics of Classical Greek art and architecture and how they are reflected in modern art and architecture; Socrates' values and ideas as reflected in his trial; how Greek gods and goddesses represent non-human entities, and how gods, goddesses, and humans interact in Greek myths) (See Instructional Goals #3, 4, and 5.) • Benchmark: Understands the role of art, literature, and mythology in Greek society (e.g., major works of Greek drama and mythology and how they reveal ancient moral values and civic culture; how the arts and literature reflected cultural traditions in ancient Greece) (See Instructional Goal #4.) • Benchmark: Understands the legacy of Greek thought and government -

Loeb Lucian Vol5.Pdf

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, LL.D. EDITED BY fT. E. PAGE, C.H., LITT.D. litt.d. tE. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. tW. H. D. ROUSE, f.e.hist.soc. L. A. POST, L.H.D. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., LUCIAN V •^ LUCIAN WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY A. M. HARMON OK YALE UNIVERSITY IN EIGHT VOLUMES V LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS MOMLXII f /. ! n ^1 First printed 1936 Reprinted 1955, 1962 Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF LTTCIAN'S WORKS vii PREFATOEY NOTE xi THE PASSING OF PEBEORiNUS (Peregrinus) .... 1 THE RUNAWAYS {FugiUvt) 53 TOXARis, OR FRIENDSHIP (ToxaHs vd amiciHa) . 101 THE DANCE {Saltalio) 209 • LEXiPHANES (Lexiphanes) 291 THE EUNUCH (Eunuchiis) 329 ASTROLOGY {Astrologio) 347 THE MISTAKEN CRITIC {Pseudologista) 371 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE GODS {Deorutti concilhim) . 417 THE TYRANNICIDE (Tyrannicidj,) 443 DISOWNED (Abdicatvs) 475 INDEX 527 —A LIST OF LUCIAN'S WORKS SHOWING THEIR DIVISION INTO VOLUMES IN THIS EDITION Volume I Phalaris I and II—Hippias or the Bath—Dionysus Heracles—Amber or The Swans—The Fly—Nigrinus Demonax—The Hall—My Native Land—Octogenarians— True Story I and II—Slander—The Consonants at Law—The Carousal or The Lapiths. Volume II The Downward Journey or The Tyrant—Zeus Catechized —Zeus Rants—The Dream or The Cock—Prometheus—* Icaromenippus or The Sky-man—Timon or The Misanthrope —Charon or The Inspector—Philosophies for Sale. Volume HI The Dead Come to Life or The Fisherman—The Double Indictment or Trials by Jury—On Sacrifices—The Ignorant Book Collector—The Dream or Lucian's Career—The Parasite —The Lover of Lies—The Judgement of the Goddesses—On Salaried Posts in Great Houses. -

Life in Two City States--- Athens and Sparta

- . CHAPTER The city-states of Sparta (above) and Athens (below) were bitter rivals. Life in Two City-States Athens and Sparta 27.1 Introduction In Chapter 26, you learned that ancient Greece was a collection of city- states, each with its own government. In this chapter, you will learn about two of the most important Greek city-states, Athens and Sparta. They not only had different forms of government, but very different ways of life. Athens was a walled city near the sea. Nearby, ships came and went from a busy port. Inside the city walls, master potters and sculptors labored in work- shops. Wealthy people and their slaves strolled through the marketplace. Often the city's citizens (free men) gathered to loudly debate the issues of the day. Sparta was located in a farming area on a plain. No walls surrounded the city. Its buildings were simple and plain compared to those of Athens. Even the clothing of the people in the streets was drab. Columns of soldiers tramped through the streets, with fierce expressions behind their bronze helmets. Even a casual visitor could see that Athens and Sparta were very different. Let's take a closer look at the way people lived in these two city-states. We'll examine each city's government, economy, education, and treatment of women and slaves. Use this graphic organizer to help you compare various aspects of life in Athens and Sparta. Life in Two City-States: Athens and Sparta 259 27.2 Comparing Two City-States Peloponnesus the penin- Athens and Sparta were both Greek cities, and they were only sula forming the southern part about 150 miles apart. -

The Birth of Rhetoric: Gorgias, Plato and Their Successors

THE BIRTH OF RHETORIC ISSUES IN ANCIENT PHILOSOPHY General editor: Malcolm Schofield GOD IN GREEK PHILOSOPHY Studies in the early history of natural theology L.P.Gerson ANCIENT CONCEPTS OF PHILOSOPHY William Jordan LANGUAGE, THOUGHT AND FALSEHOOD IN ANCIENT GREEK PHILOSOPHY Nicholas Denyer MENTAL CONFLICT Anthony Price THE BIRTH OF RHETORIC Gorgias, Plato and their successors Robert Wardy London and New York First published 1996 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 First published in paperback 1998 © 1996 Robert Wardy All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Wardy, Robert. The birth of rhetoric: Gorgias, Plato, and their successors/ Robert Wardy. p. cm.—(Issues in ancient philsophy) Includes bibliographical rerferences (p. ) and index. 1. Plato. Gorgias. 2. Rhetoric, Ancient. -

All of a Sudden: the Role of Ἐξαίφνης in Plato's Dialogues

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 1-1-2014 All of a Sudden: The Role of Ἐξαιφ́ νης in Plato's Dialogues Joseph J. Cimakasky Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Cimakasky, J. (2014). All of a Sudden: The Role of Ἐξαιφ́ νης in Plato's Dialogues (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/68 This Worldwide Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALL OF A SUDDEN: THE ROLE OF ἘΧΑΙΦΝΗΣ IN PLATO’S DIALOGUES A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Joseph Cimakasky May 2014 Copyright by Joseph Cimakasky 2014 ALL OF A SUDDEN: THE ROLE OF ἘΧΑΙΦΝΗΣ IN PLATO’S DIALOGUES By Joseph Cimakasky Approved April 9, 2014 ________________________________ ________________________________ Ronald Polansky Patrick Lee Miller Professor of Philosophy Professor of Philosophy (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ________________________________ John W. McGinley Professor of Philosophy (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ James Swindal Ronald Polansky Dean, McAnulty College Chair, Philosophy Department Professor of Philosophy Professor of Philosophy iii ABSTRACT ALL OF A SUDDEN: THE ROLE OF ἘΧΑΙΦΝΗΣ IN PLATO’S DIALOGUES By Joseph Cimakasky May 2014 Dissertation supervised by Professor Ronald Polansky There are thirty-six appearances of the Greek word ἐξαίφνης in Plato’s dialogues. -

The Same Yet Different

W 771 THE SAME YET DIFFERENT Comparing Ancient Athens and Sparta Wendy York, Middle School Teacher, McDougle Middle School James Swart, Graduate Assistant, Tennessee 4-H Youth Development Jennifer Richards, Curriculum Specialist, Tennessee 4-H Youth Development Tennessee 4-H Youth Development This lesson plan has been developed as part of the TIPPs for 4-H curriculum. The Same, Yet Different Comparing Ancient Athens and Sparta Skill Level Intermediate, 6th Grade Introduction to Content Learner Outcomes The two rivals of ancient Greece that The learner will be able to: made the most noise and gave us the most Explain the differences and similarities traditions were Athens and Sparta. They between two Greek City-States List the important contributions of each City- were close together on a map, yet far apart State in what they valued and how they lived their lives. In this lesson, students will Educational Standard(s) Supported explore the differences between these two city-states. Social Studies 6.43 Success Indicator Introduction to Methodology Learners will be successful if they: Students work in small groups to read a Identify similarities and differences of Athens and Sparta passage about the similarities and Compare and contrast information about the differences between Athens and Sparta. two city-states Students then complete a Venn Diagram outlining their findings to share with the Time Needed class. The lesson concludes by having 45 Minutes students decide on a city-state in which Materials List they would like to have lived. Student Handout- The Same, yet different Student Handout- Venn Diagram Authors York, Wendy. -

Adolescent and Young Adult Tattooing, Piercing, and Scarification

CLINICAL REPORT Guidance for the Clinician in Rendering Pediatric Care AdolescentCora C. Breuner, MD, MPH, a David A.and Levine, MD, b YoungTHE COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCEAdult Tattooing, Piercing, and Scarification Tattoos, piercing, and scarification are now commonplace among abstract adolescents and young adults. This first clinical report from the American Academy of Pediatrics on voluntary body modification will review the methods used to perform the modifications. Complications resulting from body modification methods, although not common, are discussed to provide aAdolescent Medicine Division, Department of Pediatrics, Orthopedics the pediatrician with management information. Body modification will be and Sports Medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington; and bPediatrics, Morehouse School of contrasted with nonsuicidal self-injury. When available, information also is Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia presented on societal perceptions of body modification. State laws are subject to change, and other state laws and regulations may impact the interpretation of this listing. Drs Breuner and Levine shared responsibility for all aspects of writing and editing the document and reviewing and responding to questions and comments from reviewers and the Board of Directors, and “ ” approve the final manuscript as submitted. This document is copyrighted and is property of the American Tattoos, piercings, and scarification, also known as body modifications, Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. All authors have filed conflict of interest statements with the American Academy are commonly obtained by adolescents and young adults. Previous of Pediatrics. Any conflicts have been resolved through a process reports on those who obtain tattoos, piercings, and scarification have 1 approved by the Board of Directors. -

2020Stainless Steel and Titanium

2020 stainless steel and titanium What’s behind the Intrinsic Body brand? Our master jewelers expertise and knowledge comes from an exten- sive background in industrial engineering, specifically in the aero- nautical and medical fields where precision is key. This knowl- edge and expertise informs every aspect of the Intrinsic Body brand, from design specifications, fabrication methods and tech- niques to the selection and design of components and equipment used and the best workflow practices implemented to produce each piece. Our philosophy Approaching the design and creation of fine body jewelry like the manufacture of a precision jet engine or medical device makes sense for every element that goes into the work to be of optimum quality. Therefore, only the highest grade materials are used at Intrinsic Body: medical implant grade titanium and stainless steel, fine gold, and semiprecious gemstones. All materials are chosen for their intrinsic beauty and biocompatibility. Every piece of body jew- elry produced at Intrinsic Body is made with the promise that your jewelry will be an intrinsic part of you for many years to come. We Micro - Integration endeavor to create pieces that will stand the test of time in every way. of Technology Quality Beauty Precision in the Human Body 2 Micro - Integration of Technology in the Human Body 3 Implant Grade Titanium Barbells Straight Curved 16g 14g 12g 16g 14g 12g 10g 8g Circular Surface Barbell 16g 14g 12g 14g 2.0, 2.5, or 3.0mm rise height Titanium Labrets and Labret Backs 1 - Piece Labret Back gauge 2 - Piece Labret 18g (1 - pc back + ball) 2.5mm disc gauge 16g - 14g 16g - 14g 4.0mm disc 2 - Piece Labret Back 3 - Piece Labret (disc + post + ball) (disc + post) gauge gauge 16g - 14g 16g - 14g 4 Nose Screws 3/4” length, 20g or 18g 1.5mm Prong Facted 2.0mm 1.5mm Bezel Faceted 2.0mm 1.5mm Plain Ball 1.75mm 2.0mm 8-Gem Flower 4.0mm Clickers Titanium Radiance Clicker Wearing Surface Lengths 20g or 18g 1/4" ID = 3/16" w.s.