Family Reunification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNHCR Observations on the Proposed Amendments to the Norwegian Immigration Act and Immigration Regulations

UNHCR Observations on the proposed amendments to the Norwegian Immigration Act and Immigration Regulations [Høring – tilknytningskrav for familieinnvandring] I. INTRODUCTION 1. The UNHCR Regional Representation for Northern Europe (hereafter “RRNE”) is grateful to the Ministry of Justice and Public Security for the invitation to express its views on the law proposal of 3 February 2017, which seeks to amend Section 9-9 of the Immigration Regulations, cf. to Section 51 third and fourth paragraph [adopted by the Parliament in June 2016, but not yet entered into force]. The Proposal seeks to introduce a facultative provision (a so-called attachment requirement)1 which will allow the immigration authorities to refuse applications for family reunification submitted by persons granted international protection in Norway when the person concerned is able to enjoy family life in a safe country where the family’s aggregate ties are stronger than those to Norway. The Ministry of Justice and Public Security describes the enforcement of the new rule on the attachment requirement in terms of ‘may’ clause which leaves it to the discretion of the Norwegian authorities whether to apply it or not. 2. As the agency entrusted by the United Nations General Assembly with the mandate to provide international protection to refugees and, together with Governments, seek permanent solutions to the problems of refugees,2 UNHCR has a direct interest in law and policy proposals in the field of asylum. According to its Statute, UNHCR fulfils its mandate inter alia by “[p]romoting the conclusion and ratification of international conventions for the protection of refugees, supervising their application and proposing amendments thereto [.]3 UNHCR’s supervisory responsibility is reiterated in Article 35 of the 1951 Convention4 and in Article II of the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees5 (hereafter collectively referred to as the “1951 Convention”).6 3. -

A Layman's Guide to the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

CJPME’s Vote 2019 Elections Guide « Vote 2019 » Guide électoral de CJPMO A Guide to Canadian Federal Parties’ Positions on the Middle East Guide sur la position des partis fédéraux canadiens à propos du Moyen-Orient Assembled by Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East Préparé par Canadiens pour la justice et la paix au Moyen-Orient September, 2019 / septembre 2019 © Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East Preface Préface Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East Canadiens pour la paix et la justice au Moyen-Orient (CJPME) is pleased to provide the present guide on (CJPMO) est heureuse de vous présenter ce guide Canadian Federal parties’ positions on the Middle électoral portant sur les positions adoptées par les East. While much has happened since the last partis fédéraux canadiens sur le Moyen-Orient. Canadian Federal elections in 2015, CJPME has Beaucoup d’eau a coulé sous les ponts depuis les élections fédérales de 2015, ce qui n’a pas empêché done its best to evaluate and qualify each party’s CJPMO d’établir 13 enjeux clés relativement au response to thirteen core Middle East issues. Moyen-Orient et d’évaluer les positions prônées par chacun des partis vis-à-vis de ceux-ci. CJPME is a grassroots, secular, non-partisan organization working to empower Canadians of all CJPMO est une organisation de terrain non-partisane backgrounds to promote justice, development and et séculière visant à donner aux Canadiens de tous peace in the Middle East. We provide this horizons les moyens de promouvoir la justice, le document so that you – a Canadian citizen or développement et la paix au Moyen-Orient. -

Joint Statement Calling for Sanctioning of Chinese and Hong Kong Officials and Protection for Hong Kongers at Risk of Political Persecution

Joint statement calling for sanctioning of Chinese and Hong Kong officials and protection for Hong Kongers at risk of political persecution We, the undersigned, call upon the Government of Canada to take action in light of the mass arrests and assault on civil rights following the unilateral imposition of the new National Security Law in Hong Kong. Many in Hong Kong fear they will face the same fate as the student protestors in Tiananmen Square, defenders’ lawyers, and millions of interned Uyghurs, Tibetans, and faith groups whose rights of free expression and worship are denied. We urge the Government of Canada to offer a “Safe Harbour Program” with an expedited process to grant protection and permanent residency status to Hong Kongers at risk of political persecution under the National Security Law, including international students and expatriate workers who have been involved in protest actions in Canada. Furthermore, Canada must invoke the Sergei Magnitsky Law to sanction Chinese and Hong Kong officials who instituted the National Security Law, as well as other acts violating human rights; and to ban them and their immediate family members from Canada and freeze their Canadian assets. Canada needs to work closely with international allies with shared values to institute a strong policy toward China. It is time for Canada to take meaningful action to show leadership on the world stage. Signatories: Civil society organizations Action Free Hong Kong Montreal Canada-Hong Kong Link Canada Tibet Committee Canadian Centre for Victims of -

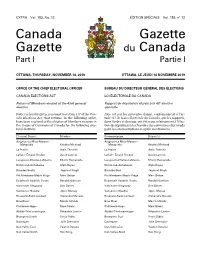

Canada Gazette, Part I

EXTRA Vol. 153, No. 12 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 153, no 12 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2019 OTTAWA, LE JEUDI 14 NOVEMBRE 2019 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER BUREAU DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 43rd general Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 43e élection election générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Can- Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’ar- ada Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, ticle 317 de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, have been received of the election of Members to serve in dans l’ordre ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élec- the House of Commons of Canada for the following elec- tion de député(e)s à la Chambre des communes du Canada toral districts: pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral District Member Circonscription Député(e) Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Matapédia Kristina Michaud Matapédia Kristina Michaud La Prairie Alain Therrien La Prairie Alain Therrien LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Burnaby South Jagmeet Singh Burnaby-Sud Jagmeet Singh Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke Randall Garrison Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke -

Core 1..16 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 17.25)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 42e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 22 No 22 Monday, February 22, 2016 Le lundi 22 février 2016 11:00 a.m. 11 heures PRAYER PRIÈRE GOVERNMENT ORDERS ORDRES ÉMANANT DU GOUVERNEMENT The House resumed consideration of the motion of Mr. Trudeau La Chambre reprend l'étude de la motion de M. Trudeau (Prime Minister), seconded by Mr. LeBlanc (Leader of the (premier ministre), appuyé par M. LeBlanc (leader du Government in the House of Commons), — That the House gouvernement à la Chambre des communes), — Que la Chambre support the government’s decision to broaden, improve, and appuie la décision du gouvernement d’élargir, d’améliorer et de redefine our contribution to the effort to combat ISIL by better redéfinir notre contribution à l’effort pour lutter contre l’EIIL en leveraging Canadian expertise while complementing the work of exploitant mieux l’expertise canadienne, tout en travaillant en our coalition partners to ensure maximum effect, including: complémentarité avec nos partenaires de la coalition afin d’obtenir un effet optimal, y compris : (a) refocusing our military contribution by expanding the a) en recentrant notre contribution militaire, et ce, en advise and assist mission of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in développant la mission de conseil et d’assistance des Forces Iraq, significantly increasing intelligence capabilities in Iraq and armées canadiennes (FAC) en Irak, en augmentant theatre-wide, deploying CAF medical personnel, -

PRISM::Advent3b2 17.25

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 148 Ï NUMBER 015 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 42nd PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, February 3, 2016 Speaker: The Honourable Geoff Regan CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 767 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, February 3, 2016 The House met at 2 p.m. My riding consists of the cities of Belleville, Quinte West, as well as Prince Edward County. It is a great honour to be the first MP to represent this riding. Prayer I would like to congratulate all of my colleagues in this House for their victories. I encourage all members to come and explore the Ï (1405) spectacular Bay of Quinte. It will not disappoint. [English] I also rise today to recognize the important work being done by The Speaker: It being Wednesday, we will now have the singing Gleaners Food Bank and Tri-County Warehouse. This past weekend, of the national anthem led by the hon. member for Nanaimo— I was pleased to attend their fundraiser which raised over $23,000. Ladysmith. What began as a pilot project in 1986 now distributes food baskets to over 150 non-profit organizations. In 2015 alone they distributed [Members sang the national anthem] almost 9,000 food hampers across the area. I know that all members can appreciate the important roles STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS organizations like this play in addressing food insecurity. [Translation] *** PAY EQUITY SCREAMIN BROTHERS Ms. Monique Pauzé (Repentigny, BQ): Mr. Speaker, pay equity is one of our primary concerns. This issue is especially important to Ms. Rachael Harder (Lethbridge, CPC): Mr. -

A Parliamentarian's

A Parliamentarian’s Year in Review 2018 Table of Contents 3 Message from Chris Dendys, RESULTS Canada Executive Director 4 Raising Awareness in Parliament 4 World Tuberculosis Day 5 World Immunization Week 5 Global Health Caucus on HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria 6 UN High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis 7 World Polio Day 8 Foodies That Give A Fork 8 The Rush to Flush: World Toilet Day on the Hill 9 World Toilet Day on the Hill Meetings with Tia Bhatia 9 Top Tweet 10 Forging Global Partnerships, Networks and Connections 10 Global Nutrition Leadership 10 G7: 2018 Charlevoix 11 G7: The Whistler Declaration on Unlocking the Power of Adolescent Girls in Sustainable Development 11 Global TB Caucus 12 Parliamentary Delegation 12 Educational Delegation to Kenya 14 Hearing From Canadians 14 Citizen Advocates 18 RESULTS Canada Conference 19 RESULTS Canada Advocacy Day on the Hill 21 Engagement with the Leaders of Tomorrow 22 United Nations High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis 23 Pre-Budget Consultations Message from Chris Dendys, RESULTS Canada Executive Director “RESULTS Canada’s mission is to create the political will to end extreme poverty and we made phenomenal progress this year. A Parliamentarian’s Year in Review with RESULTS Canada is a reminder of all the actions decision makers take to raise their voice on global poverty issues. Thank you to all the Members of Parliament and Senators that continue to advocate for a world where everyone, no matter where they were born, has access to the health, education and the opportunities they need to thrive. “ 3 Raising Awareness in Parliament World Tuberculosis Day World Tuberculosis Day We want to thank MP Ziad Aboultaif, Edmonton MPs Dean Allison, Niagara West, Brenda Shanahan, – Manning, for making a statement in the House, Châteauguay—Lacolle and Senator Mobina Jaffer draw calling on Canada and the world to commit to ending attention to the global tuberculosis epidemic in a co- tuberculosis, the world’s leading infectious killer. -

List of Mps on the Hill Names Political Affiliation Constituency

List of MPs on the Hill Names Political Affiliation Constituency Adam Vaughan Liberal Spadina – Fort York, ON Alaina Lockhart Liberal Fundy Royal, NB Ali Ehsassi Liberal Willowdale, ON Alistair MacGregor NDP Cowichan – Malahat – Langford, BC Anthony Housefather Liberal Mount Royal, BC Arnold Viersen Conservative Peace River – Westlock, AB Bill Casey Liberal Cumberland Colchester, NS Bob Benzen Conservative Calgary Heritage, AB Bob Zimmer Conservative Prince George – Peace River – Northern Rockies, BC Carol Hughes NDP Algoma – Manitoulin – Kapuskasing, ON Cathay Wagantall Conservative Yorkton – Melville, SK Cathy McLeod Conservative Kamloops – Thompson – Cariboo, BC Celina Ceasar-Chavannes Liberal Whitby, ON Cheryl Gallant Conservative Renfrew – Nipissing – Pembroke, ON Chris Bittle Liberal St. Catharines, ON Christine Moore NDP Abitibi – Témiscamingue, QC Dan Ruimy Liberal Pitt Meadows – Maple Ridge, BC Dan Van Kesteren Conservative Chatham-Kent – Leamington, ON Dan Vandal Liberal Saint Boniface – Saint Vital, MB Daniel Blaikie NDP Elmwood – Transcona, MB Darrell Samson Liberal Sackville – Preston – Chezzetcook, NS Darren Fisher Liberal Darthmouth – Cole Harbour, NS David Anderson Conservative Cypress Hills – Grasslands, SK David Christopherson NDP Hamilton Centre, ON David Graham Liberal Laurentides – Labelle, QC David Sweet Conservative Flamborough – Glanbrook, ON David Tilson Conservative Dufferin – Caledon, ON David Yurdiga Conservative Fort McMurray – Cold Lake, AB Deborah Schulte Liberal King – Vaughan, ON Earl Dreeshen Conservative -

Scorched Earth: Responding to Conflict, Human Rights Violations and Manmade Humanitarian Catastrophe in South Sudan

SCORCHED EARTH: RESPONDING TO CONFLICT, HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AND MANMADE HUMANITARIAN CATASTROPHE IN SOUTH SUDAN Report of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development Hon. Robert D. Nault Chair Subcommittee on International Human Rights Michael Levitt Chair JUNE 2017 42nd PARLIAMENT, FIRST SESSION Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. Nothing in this permission abrogates or derogates from the privileges, powers, immunities and rights of the House of Commons and its Committees. For greater certainty, this permission does not affect the prohibition against impeaching or questioning the proceedings of the House of Commons in courts or otherwise. -

THE USE of INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES in PROCEEDINGS of the HOUSE of COMMONS and COMMITTEES Report of the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs

THE USE OF INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES IN PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS AND COMMITTEES Report of the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs The Honourable Larry Bagnell, Chair JUNE 2018 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION The proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees are hereby made available to provide greater public access. The parliamentary privilege of the House of Commons to control the publication and broadcast of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees is nonetheless reserved. All copyrights therein are also reserved. Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. -

FAMILY REUNIFICATION for REFUGEE and MIGRANT CHILDREN CHILDREN MIGRANT and Standards and Promising Practices Practices Promising and Standards

FAMILY REUNIFICATION FOR REFUGEE AND MIGRANT CHILDREN PREMS 003720 Standards and promising practices FAMILY REUNIFICATION FOR REFUGEE AND MIGRANT CHILDREN Standards and promising practices Council of Europe French edition: Regroupement familial pour les enfants réfugiés et migrants – Normes juridiques et pratiques prometteuses The opinions expressed in this work are the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. All requests concerning the reproduction or translation of all or part of this document should be addressed to the Directorate of Communication (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex or publishing@ coe.int). All other correspondence concerning this document should be addressed to the Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary General on Migration and Refugees. Cover and layout : Documents and Publications Production Department (SPDP), Council of Europe Photo: © Shutterstock © Council of Europe, April 2020 Printed at the Council of Europe Contents ABOUT THE AUTHORS 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 LIST OF ACRONYMS 8 INTRODUCTION 9 Scope of the handbook 10 Methodology 11 Structure of the handbook 12 KEY FINDINGS 13 DEFINITIONS 15 PART I – RELEVANT LEGAL PRINCIPLES AND PROVISIONS CONCERNING FAMILY LIFE AND FAMILY REUNIFICATION 17 CHAPTER 1. FAMILY REUNIFICATION IN HUMAN RIGHTS LAW 19 1.1. State obligations relating to the right to family life 20 1.2. Definition of the family 25 CHAPTER 2. FAMILY REUNIFICATION IN INTERNATIONAL REFUGEE LAW AND IN THE UNITED NATIONS GLOBAL COMPACTS 28 CHAPTER 3. FAMILY REUNIFICATION IN EU LAW 30 3.1. Charter of Fundamental Rights 30 3.2. EU Family Reunification Directive 30 3.3. EU Dublin Regulation 31 3.4. -

George Committees Party Appointments P.20 Young P.28 Primer Pp

EXCLUSIVE POLITICAL COVERAGE: NEWS, FEATURES, AND ANALYSIS INSIDE HARPER’S TOOTOO HIRES HOUSE LATE-TERM GEORGE COMMITTEES PARTY APPOINTMENTS P.20 YOUNG P.28 PRIMER PP. 30-31 CENTRAL P.35 TWENTY-SEVENTH YEAR, NO. 1322 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 2016 $5.00 NEWS SENATE REFORM NEWS FINANCE Monsef, LeBlanc LeBlanc backs away from Morneau to reveal this expected to shed week Trudeau’s whipped vote on assisted light on deficit, vision for non- CIBC economist partisan Senate dying bill, but Grit MPs predicts $30-billion BY AbbaS RANA are ‘comfortable,’ call it a BY DEREK ABMA Senators are eagerly waiting to hear this week specific details The federal government is of the Trudeau government’s plan expected to shed more light on for a non-partisan Red Cham- Charter of Rights issue the size of its deficit on Monday, ber from Government House and one prominent economist Leader Dominic LeBlanc and Members of the has predicted it will be at least Democratic Institutions Minister Joint Committee $30-billion—about three times Maryam Monsef. on Physician- what the Liberals promised dur- The appearance of the two Assisted ing the election campaign—due to ministers at the Senate stand- Suicide, lower-than-expected tax revenue ing committee will be the first pictured at from a slow economy and the time the government has pre- a committee need for more fiscal stimulus. sented detailed plans to reform meeting on the “The $10-billion [deficit] was the Senate. Also, this is the first Hill. The Hill the figure that was out there official communication between Times photograph based on the projection that the the House of Commons and the by Jake Wright economy was growing faster Senate on Mr.