Introduction the Reverse Peephole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barnes & Noble

Short Case Barnes & Noble Turning the page to compete in a digital book market This case was written by Joachim Stonig (University of St. Gallen). It is intended to be used as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a management situation. The case was compiled from published sources. © Joachim Stonig, January 2020, Version 1.1, University of St. Gallen No part of this publication may be copied, stored, transmitted, reproduced or distributed in any form or medium whatsoever without the permission of the copyright owner. 1 In June 2019, investment firm Elliott Management announced that it would acquire Barnes & 1 Noble for about $683 million and take the company private.0F The largest U.S. book retailer had experienced a long decline over the last decade. The number of stores dropped by more than 100 since their peak in 2009, from 726 to 630 in 2018, and revenue fell by more than $2 billion in the same timeframe. James Daunt, who runs the British bookseller Waterstones since 2011, became CEO of the ailing company. James Daunt is known to be book enthusiast who believes in the cultural and emotional value of print. With the funds from Elliott and less short-term financial pressure from the stock market, he hopes to change the fortunes of Barnes & Noble. His initial assessment of the company, however, was less than flattering: “Frankly, at the moment you want to love Barnes & Noble, but when you leave the store you feel mildly betrayed. […] Not massively, but mildly. -

The Lovely Serendipitous Experience of the Bookshop’: a Study of UK Bookselling Practices (1997-2014)

‘The Lovely Serendipitous Experience of the Bookshop’: A Study of UK Bookselling Practices (1997-2014). Scene from Black Books, ‘Elephants and Hens’, Series 3, Episode 2 Chantal Harding, S1399926 Book and Digital Media Studies Masters Thesis, University of Leiden Fleur Praal, MA & Prof. Dr. Adriaan van der Weel 28 July 2014 Word Count: 19,300 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter One: There is Value in the Model ......................................................................................................... 10 Chapter Two: Change and the Bookshop .......................................................................................................... 17 Chapter Three: From Standardised to Customised ....................................................................................... 28 Chapter Four: The Community and Convergence .......................................................................................... 44 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................................................... 51 Bibliography: ............................................................................................................................................................... 54 Archival and Primary Sources: ....................................................................................................................... -

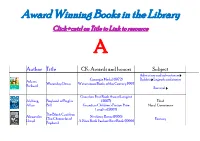

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+Cntrl on Title to Link to Resource A

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+cntrl on Title to Link to resource A Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Adventure and adventurers › Carnegie Medal (1972) Rabbits › Legends and stories Adams, Watership Down Waterstones Books of the Century 1997 Richard Survival › Guardian First Book Award Longlist Ahlberg, Boyhood of Buglar (2007) Thief Allan Bill Guardian Children's Fiction Prize Moral Conscience Longlist (2007) The Black Cauldron Alexander, Newbery Honor (1966) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1966) Prydain) Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject The Book of Three Alexander, A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1965) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd Prydain Book 1) A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1967) Alexander, Castle of Llyr Fantasy Lloyd Princesses › A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1968) Taran Wanderer (The Alexander, Fairy tales Chronicles of Lloyd Fantasy Prydain) Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2003) Whitbread (Children's Book, 2003) Boston Globe–Horn Book Award Almond, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962 › The Fire-eaters (Fiction, 2004) David Great Britain › History Nestlé Smarties Book Prize (Gold Award, 9-11 years category, 2003) Whitbread Shortlist (Children's Book, Adventure and adventurers › Almond, 2000) Heaven Eyes Orphans › David Zilveren Zoen (2002) Runaway children › Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2000) Amateau, Chancey of the SIBA Book Award Nominee courage, Gigi Maury River Perseverance Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Angeli, Newbery Medal (1950) Great Britain › Fiction. › Edward III, Marguerite The Door in the Wall Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1961) 1327-1377 De A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1950) Physically handicapped › Armstrong, Newbery Honor (2006) Whittington Cats › Alan Newbery Honor (1939) Humorous stories Atwater, Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1958) Mr. -

British Bookselling Today: to Whom Does the Future Belong?

LOGOS 8(1)/sc/ 2nd 31/10/06 8:55 pm Page 24 LOGOS British bookselling today: To whom does the future belong? Tim Coates Bookselling in the UK today is in as nervous a period as I can remember. The last twenty years have been dominated by the development of new, large, national bookselling chains, most notably Waterstones and Dillons. These chains have brought with them a transfer of power from pub- lishers to retailers. The oldest and largest chain, W H Smith, finds itself usurped and seriously strug- A graduate of University College, gling to hold on to what once was its dominant Oxford and the University of market share. In its fight to survive, it has played the final card in its hand by bringing to an end the Stirling, Tim Coates joined Net Book Agreement, which for 100 years had W H Smith, the UK’s largest been one of the world’s strongest and most strenu- bookseller/newsagent/stationery ously defended instruments of resale price mainte- chain, as a business analyst in nance. This change has opened a Pandora’s box 1975. After a stint as Marketing into which we are only just beginning to see. The flourishing publishing industry seems to be losing its Director of Webster’s bookshops collective confidence and we are witnessing a spate (which were acquired by of major financial crises which imply a period of W H Smith), he was appointed instability ahead. Managing Director of all In my view, the British book industry is suffering from the consequences of too many years specialist bookshops owned by of looking inwards for inspiration and ignoring the Smiths, under the name of wishes of its customers. -

Working at Waterstones

Working at Waterstones: Staff profiles This book contains 40 staff accounts of working at Waterstones stores across the UK. It has been paid for and published by more than 11,500 staff, authors and customers who are calling for the Real Living Wage for all Waterstones employees. All staff names in this book have been changed to the names of the staff member's favourite author, to protect their identity. 1 Contents Worker 1: Ruth Park 7 Worker 2: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie 8 Worker 3: Leo Tolstoy 9 Worker 4: Muriel Spark 8 Worker 5: Henry Thoreau 10 Worker 6: Virginia Woolf 11 Worker 7: Naomi Klein 12 Worker 8: William S. Burroughs 13 Worker 9: Emily Dickinson 15 Worker 10: Ta-Nehisi Coates 16 Worker 11: Elizabeth Smart 17 Worker 12: Virgil 18 Worker 13: Philip Pullman 19 2 Contents Worker 14: Jane Aust en 20 Worker 15: Mary Shelly 21 Worker 16: Fyodor Dostoevsky 22 Worker 17: Neil Gaiman 23 Worker 18: Salman Rushdie 24 Worker 19: Ernst Hemingway 25 Worker 20: Alan Moore 26 Worker 21: JRR Tolkien 27 Worker 22: Sylvia Plath 28 Worker 23: Benjamin Zephaniah 29 Worker 24: Oscar Wilde 30 Worker 25: Emily Brontë 31 Worker 26: Isaac Asimov 32 Worker 27: James Baldwin 33 3 Contents Worker 28: Doris Lessing 20 Worker 29: Deborah Levy 21 Worker 30: Truman Capote 22 Worker 31: Vladimir Nabokov 23 Worker 32: William Shakespeare 24 Worker 33: Gabriel García Márquez 25 Worker 34: Zadie Smith 26 Worker 35: F. Scott Fitzgerald 27 Worker 36: Haruki Murakami 28 Worker 37: C. -

German Literature on the Middle East: Discourses and Practices, 1000-1989 Book PDF Presentation Download Nina Berman

German Literature On The Middle East: Discourses And Practices, 1000-1989 Nina Berman Nina Berman: German Literature on the Middle East. Discourses Books: German Literature on the Middle East: Discourses and Practices, 1000-1989 Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011 Impossible Missions:. German Literature on the Middle East: Discourses and Practices,. - Google Books Result German Literature on the Middle East: Discourses and Practices. NEW German Literature ON THE Middle East Discourses AND. Mar 7, 2013. The German-Iraqi writer Hussain Al-Mozany's novel Der Marschländer 1999 makes an important German Literature on the Middle East: Discourses and Practices, 1000–1989. Discourses and Practices, 1000–1989. ? New German Literature on The Middle East Discourses and. - eBay Aug 30, 2013. German Literature on the Middle East: Discourses and Practices, 1000-1989. by. Nina Berman. Series: Social History, Popular Culture and German Literature on the Middle East: Discourses and Practices. German Literature on the Middle East: Discourses and Practices, 1000-1989 Berman in Books, Comics & Magazines, Non-Fiction, Other Non-Fiction eBay. Nina Berman Department of Comparative Studies NEW German Literature on the Middle East: Discourses and Practices, 1000-1989 by in Books, Nonfiction eBay. German Literature on the Middle East: Discourses and Practices, 1000–1989. complex relationship between “textual discourses and nontextual practices” p. Alwan's Quest of Home: Re-Mapping Heimat and the Nation in. She is the author of German Literature on the -

Waterstones Booksellers Limited 203-206 Piccadilly London W1J 9HD

Waterstones Booksellers Limited 203-206 Piccadilly London W1J 9HD. www.waterstones.com May 2012 Dear Thank you for your enquiry about setting up a trading relationship with Waterstones. We use wholesalers such as Gardners as our source of supply for many publishers’ titles rather than trading directly with them and we would source your titles in this way. What this means for you is that instead of receiving disparate orders from various individual branches of Waterstones, Gardners will collate all our store orders and will send them directly to you on our behalf. You will not need to deliver stock to a variety of locations; all deliveries can be dispatched to Gardners in a single drop. Billing will also be consolidated so you will only need to maintain one single account with Gardners. None of this has any effect on the number or volume of titles that we stock or order, but any agreed orders will be sent to and fulfilled by Gardners rather than placed directly with you. This letter sets out the steps you need to take in order to set this up and includes an application form and a set of Frequently Asked Questions to assist you. These steps are very straightforward; ensure that your book has an ISBN and Barcode number, register your title information with Nielsen BookData and set up a trading relationship with Gardners. 1. Ensure that your book has an ISBN and Barcode number. We can only carry books that have both an International Standard Book Number (ISBN) and a Bookland European Article Number (EAN) barcode. -

Nostalgia and the Physical Book

NOSTALGIA AND THE PHYSICAL BOOK Cheyenne White A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2021 Committee: Kristen Rudisill, Advisor Esther Clinton © 2021 Cheyenne White All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Kristen Rudisill, Advisor We are used to seeing books, handling them, reading them, but we are not so used to analyzing our relationship to the form of the object, yet in this thesis, I argue that the very shape and composition of books has an impact on our interactions and relationships with them. By looking at the material book, we must confront the cultural, social, and individual significance that these material objects are imbued with. The physical attributes of books, from the smell of ink and paper to the distinct feel of a hefty hardback or flexible paperback, contribute specific things to culture and an individual’s experience as physical books carry commercial, aesthetic, and emotional value. By looking at material culture studies, memory and commemoration, as well as theory behind nostalgia, I argue that the physical book can be both a powerful object and carrier of social meaning by utilizing Grant McCracken’s notion of displaced meaning, academic studies of nostalgia, the science of book scent, bookshop curation, and book collecting, along with essay compilations by booklovers. From the affective power of the sensory aspects of books to book collecting and book spaces, the materiality of the book is revealed not as a mere vessel for texts but as essential to the physical book’s ability to anchor memory, emotion, and identity. -

The Proposed Acquisition of the Book Depository by Amazon

THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION OF THE BOOK DEPOSITORY BY AMAZON SUBMISSION FROM THE BOOKSELLERS ASSOCIATION TO THE OFFICE OF FAIR TRADING To: Tim Geer, Esq., Mergers@OFT From: THE BOOKSELLERS ASSOCIATION 272 VAUXHALL BRIDGE ROAD LONDON SW1V 1BA Tel: 020 7802 0802; Fax: 020 7802 0803; e-mail: [email protected] www.booksellers.org.uk Amazon purchase of The Book Depository: BA submission to the OFT 1 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 The Booksellers Association welcomes the opportunity to give its views on the proposed acquisition of The Book Depository [“TBD”] by Amazon. BA membership 1.2 The Booksellers Association [the “BA”] is a trade association, based in London SW1, currently with 3,683 bookselling outlets in membership, covering 1,010 businesses. 1.3 Our members cover a diverse range of different bookselling businesses - large high street chains with mixed businesses (eg W H Smith); large specialist bookselling chains (eg Waterstone’s); independents (eg Daunts); library suppliers (eg Askews); school suppliers (eg Heath Educational Book Supplies); specialist Internet booksellers (eg Eddington Hook); supermarkets (eg Tesco); and the two national wholesalers (Bertrams and Gardners). 1.4 Amazon used to be a BA member but withdrew in 2005; TBD has never been a member. 1.5 BA members sell to all markets (consumer – fiction/ non-fiction/ reference/ children’s; academic – academic/ professional/ school/ English Language Teaching) from terrestrial shops and over the internet in a variety of different formats (hardback, paperback, audiobook and now e-book). The BA 1.6 The BA helps its members to sell more books; operate from a lower cost base; improve competitiveness and productivity; network with others in the ‘book world’ and further afield and, most importantly, to represent their views…. -

Annual Report 2011/2012

The Power of Partnership Thirty-ninth Annual Report and Accounts 2011/12 British Library The Power of Partnership Thirty-ninth Annual Report and Accounts 2011/12 Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 4(3) of the British Library Act 1972. Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 11 July 2012 Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers 11 July 2012 Laid before the National Assembly for Wales by the [First Secretary] 11 July 2012 Laid before the National Assembly for Northern Ireland 11 July 2012 HC 243 SG/2012/97 London: The Stationery Office £21.25 © British Library (2012) The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental and agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as British Library copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to [email protected] This publication is available for download at www.official-documents.gov.uk This document is also available from our website at www.bl.uk/annualreport2011-12 ISBN: 9780102976212 Printed in the UK for The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. ID: 2482008 07/12 Printed on 100% recycled paper. The Power of Partnership Contents Chairman’s statement 5 Chief Executive’s -

The Life and Death of an Ace Peter Kilduff Contents

RED BARON THE LIFE AND DEATH OF AN ACE PETER KILDUFF CONTENTS This book is dedicated to my longtime “co-pilot” Karl F. Kilduff, who knows the best route in many areas, and shares his expertise with me with boundless generosity. Introduction 6 A DAVID & CHARLES BOOK Copyright © David & Charles Limited 2007, 2008 Foreword by the current Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen 10 David & Charles is an F+W Publications Inc. company 4700 East Galbraith Road Cincinnati, OH 45236 1 First Blood 12 First published in the UK in 2007 First paperback edition 2008 2 The Glory of its Name 20 Text copyright © Peter Kilduff 2007,2008 3 The Sky Arena 36 Peter Kilduff has asserted his right to be identified as author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. 4 Winds of Change 56 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or 5 Flying with Boelcke 68 mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. 6 Preparing for Command 86 The publisher has made every reasonable effort to contact the copyright holders of images and text. If there have been any omissions, however, David & Charles will be pleased to insert the appropriate acknowledgment at a subsequent printing. 7 The Red Baron Arises 100 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 8 Bloody April 1917 122 ISBN-13: 978-0-7153-2809-5 hardback ISBN-10: 0-7153-2809-3 hardback 9 Deutschland -

An Evaluation of the Impact Upon Productivity of Ending Resale Price Maintenance on Books

An evaluation of the impact upon productivity of ending resale price maintenance on books February 2008 Report prepared for the OFT by the Centre for Competition Policy at University of East Anglia OFT981 © Crown copyright 2008 This publication (excluding the OFT logo) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as crown copyright and the title of the publication specified. Report prepared for the OFT by the Centre for Competition Policy at University of East Anglia FOREWORD This report was commissioned by the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) from the Centre for Competition Policy at the University of East Anglia. The team from University of East Anglia was asked to examine how the ending of resale price maintenance on Books in 1997 affected productivity in book publishing and retailing. Any views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the OFT nor the legal position under existing competition law which the OFT applies in exercise of its competition law enforcement functions. This report is part of the OFT's Economic Discussion Paper series, and is intended to inform current discussion within the competition policy community in the UK about cooperation between purchasers. If you would like to comment on the paper, please write to me, Amelia Fletcher, at the address below. The OFT welcomes suggestions for future research topics on all aspects of UK competition and