Fifty Years of Quasars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

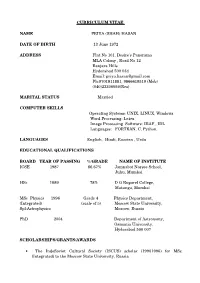

Curriculum Vitae Name

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME PRIYA (SHAH) HASAN DATE OF BIRTH 13 June 1972 ADDRESS Flat No 101, Desire©s Panorama MLA Colony , Road No 12 Banjara Hills Hyderabad 500 034 Email: [email protected] Ph:9701811881, 9866619519 (Mob) (040)23306959(Res) MARITAL STATUS Married COMPUTER SKILLS Operating Systems: UNIX, LINUX, Windows Word Processing: Latex Image Processing Software: IRAF , IDL Languages: FORTRAN, C, Python. LANGUAGES English, Hindi, Russian , Urdu EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS BOARD YEAR OF PASSING %/GRADE NAME OF INSTITUTE ICSE 1987 86.67% Jamnabai Narsee School, Juhu, Mumbai HSc 1989 78% D G Ruparel College, Matunga, Mumbai MSc Physics 1996 Grade 4 Physics Department, (Integrated) (scale of 5) Moscow State University, Spl:Astrophysics Moscow, Russia PhD 2004 Department of Astronomy, Osmania University, Hyderabad 500 007 SCHOLARSHIPS/GRANTS/AWARDS The IndoSoviet Cultural Society (ISCUS) scholar (19901996) for MSc (Integrated) to the Moscow State University, Russia IndoFrench Centre for the Promotion of Advanced Research(IFPCAR) (2004 2006) Post Doctoral Fellowship at IUCAA, Pune Department of Science and Technology (DST) Women Scientist Scheme (2006 2009) DST project under the Women Scientist Scheme (SR/WOSA/PS- 26/2005) entitled ªPhotometric studies of star clusters using the 2MASS and observationsº. International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP ) Invited under the International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP) by the US Consulate, Hyderabad to visit and interact with American Universities and Research Centres for a period of three weeks in August 2011. TRAVEL GRANT: Department of Science and Technology (DST), International Travel Support (ITS) to present a paper at the conference "From Stars to Galaxies", 2010, at the University of Florida, Gainesville. -

Khag L October 2015

No. 104 KHAG L OCTOBER 2015 Editor : Editorial Assistant : Somak Raychaudhury Manjiri Mahabal ([email protected]) ([email protected]) A quarterly bulletin of the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics ISSN 0972-7647 (An autonomous institution of the University Grants Commission) Available online at http://ojs.iucaa.ernet.in/ AT THE HELM... Professor Somak Raychaudhury has taken over as the Director, IUCAA, with effect from September 1, 2015 on my superannuation. He had his undergraduate education at Presidency College, Kolkata and the University of Oxford. For his Ph.D. he worked with Professor Donald Lynden- Bell at the Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, UK, followed by post- doctoral fellowships at the Harvard- Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, Harvard University, USA, and at the Institute of Astronomy. He was a faculty member at IUCAA during 1995 - 2000, and then at the University of Birmingham. In 2012, he joined the Presidency University, Kolkata, where he Somak Raychaudhury (Left) and Ajit Kembhavi was the Head of the Department of Physics and Dean, Natural Sciences. and will be greatly concerned Contents... with the University Programmes Reports of Past Events 1,2,3,4,5,6 Professor Raychaudhury’s research interests of IUCAA. Announcements 7 are in the areas of Galaxy Groups, Galaxy Welcome and Farewell 8 The IUCAA family looks forward Clusters and Large Scale Structures, and New Associates 9 carries out Observational work in the to his leadership in taking IUCAA Seminars 10 Optical, Radio and X-ray domains. Professor further along the path of progress. Visitors 10,11 Raychaudhury is deeply involved in Congratulations 11 Know Thy Birds 12 teaching of Astronomy and Public Outreach, Ajit Kembhavi KHAG L | IJmoc | No. -

Khagol Bulletin Apr 2017

No. 110 KHAG L APRIL 2017 Editor : Editorial Assistant : Aseem Paranjape Manjiri Mahabal ([email protected]) ([email protected]) A quarterly bulletin of the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics Available online at http://ojs.iucaa.in/ ISSN 0972-7647 (An autonomous institution of the University Grants Commission) Follow us on our face book page : inter-university-centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics Contents... Reports of Past Events 1 to 10 Congratulations 2 Public Outreach Activities 8, 9 Workshop on Aspects of Gravity Farewell 10 Visitors 10, 11 and Cosmology Know Thy Birds 12 An international workshop on Aspects of Gravity and Cosmology was organised at IUCAA, involving some of the large surveys during March 7 - 9, 2017, covering a broad range of topics in classical and quantum aspects of currently in operation, such as the Dark gravitation and cosmology. The lively and eclectic academic programmes covered topics as Energy Survey and the search for diverse as emergent gravity, cosmo-biology, including a historical survey of observational cosmological neutral hydrogen. cosmology, as the subject progressed from the early days of IUCAA up to the latest results, Along with the academic programmes, one session concentrated on issues in Public Outreach in Science, including talks on contd. on page 2... On February 28, 2017, it was revealed that IUCAA Science Day celebrations was just as popular, be it a Sunday or a weekday! The celebrations of National Science Day (this time mid- week on a Tuesday) attracted numerous groups of students from in and around Pune, and as far as Parbhani (about 10 hours bus journey to Pune). -

NL#132 October

October 2006 Issue 132 AAS NEWSLETTER A Publication for the members of the American Astronomical Society PRESIDENT’S COLUMN J. Craig Wheeler, [email protected] August is a time astronomers devote to travel, meetings, and writing papers. This year, our routine is set 4-5 against the background of sad and frustrating wars and new terror alerts that have rendered our shampoo Calgary Meeting suspect. I hope that by the time this is published there is a return to what passes for normalcy and some Highlights glimmer of reason for optimism. In this summer season, the business of the Society, while rarely urgent, moves on. The new administration 6 under Executive Officer Kevin Marvel has smoothly taken over operations in the Washington office. The AAS Final transition to a new Editor-in-Chief of the Astrophysical Journal, Ethan Vishniac, has proceeded well, with Election some expectation that the full handover will begin earlier than previously planned. Slate The Society, under the aegis of the Executive Committee, has endorsed the efforts of Senators Mikulksi and Hutchison to secure $1B in emergency funding for NASA to make up for some of the costs of shuttle 6 return to flight and losses associated with hurricane Katrina. It remains to be seen whether this action 2007 AAS will survive the budget process. The Executive Committee has also endorsed a letter from the American Renewals Institute of Physics supporting educators in Ohio who are fending off an effort there to include intelligent design in the curriculum. 13 Interestingly, the primary in Connecticut was of relevance to the Society. -

Ligo-India Proposal for an Interferometric Gravitational-Wave Observatory

LIGO-INDIA PROPOSAL FOR AN INTERFEROMETRIC GRAVITATIONAL-WAVE OBSERVATORY IndIGO Indian Initiative in Gravitational-wave Observations PROPOSAL FOR LIGO-INDIA !"#!$ Indian Initiative in Gravitational wave Observations http://www.gw-indigo.org II Title of the Project LIGO-INDIA Proposal of the Consortium for INDIAN INITIATIVE IN GRAVITATIONAL WAVE OBSERVATIONS IndIGO to Department of Atomic Energy & Department of Science and Technology Government of India IndIGO Consortium Institutions Chennai Mathematical Institute IISER, Kolkata IISER, Pune IISER, Thiruvananthapuram IIT Madras, Chennai IIT, Kanpur IPR, Bhatt IUCAA, Pune RRCAT, Indore University of Delhi (UD), Delhi Principal Leads Bala Iyer (RRI), Chair, IndIGO Consortium Council Tarun Souradeep (IUCAA), Spokesperson, IndIGO Consortium Council C.S. Unnikrishnan (TIFR), Coordinator Experiments, IndIGO Consortium Council Sanjeev Dhurandhar (IUCAA), Science Advisor, IndIGO Consortium Council Sendhil Raja (RRCAT) Ajai Kumar (IPR) Anand Sengupta(UD) 10 November 2011 PROPOSAL FOR LIGO-INDIA II PROPOSAL FOR LIGO-INDIA LIGO-India EXECUTIVE SUMMARY III PROPOSAL FOR LIGO-INDIA IV PROPOSAL FOR LIGO-INDIA This proposal by the IndIGO consortium is for the construction and subsequent 10- year operation of an advanced interferometric gravitational wave detector in India called LIGO-India under an international collaboration with Laser Interferometer Gravitational–wave Observatory (LIGO) Laboratory, USA. The detector is a 4-km arm-length Michelson Interferometer with Fabry-Perot enhancement arms, and aims to detect fractional changes in the arm-length smaller than 10-23 Hz-1/2 . The task of constructing this very sophisticated detector at the limits of present day technology is facilitated by the amazing opportunity offered by the LIGO Laboratory and its international partners to provide the complete design and all the key components required to build the detector as part of the collaboration. -

To, Prof. Ajit Kembhavi, President, ASI CC

To, Prof. Ajit Kembhavi, President, ASI CC : Prof. Dipankar Banerjee, Secretary, ASI Subject : Formation of Working Group for Gender Equity Dear Sir, We, the undersigned, members of the Indian Astronomy & Astrophysics community (from a number of academic institutions), would like to request you for the formation of a working group for gender equity under the aegis of ASI. To this effect we hereby submit a formal proposal giving details of the rational behind such a working group and a brief outline of the role we would like the working group to play. We hope you would take cognizance of the fact that a significant fraction of our community feel that the formation of such a group is the need of the hour. For the Working Group to better serve the needs of the entire astronomy community, it would be advantageous if its constituted members reflect the diversity of the community in gender, age, affiliation, geographical region etc. In addition, in the interest of promoting equity in gender representation, we feel it is best chaired by a woman astronomer. Hoping to receive a positive response from you. Yours sincerely, The Proposers of the Working Group The Proposers : A core group of people (Preeti Kharb, Sushan Konar, Niruj Mohan, L. Resmi, Jasjeet Singh Bagla, Nissim Kanekar, Prajval Shastri, Dibyendu Nandi etc.) have been working towards sensitising the Indian Astronomical community about gender related issues and proposing the formation of a working group, with significant input from a number of others. However, a large section of the community have been supportive of this activity and would like to be a part of this initiative. -

The Initiative in India

2004-11-25 file:/usr1/pathak/ar2.html #1 Vol:21 Iss:23 URL: http://www.flonnet.com/fl2123/stories/20041119002610100.htm ASTRONOMY The initiative in India R. RAMACHANDRAN INDIA has a fairly large community of astronomers with institutes like the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA) and the National Centre for Radio Astrophysics (NCRA) in Pune and the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IIA) in Bangalore dedicated to research in astronomy. It has a number of astronomical facilities with moderately sized optical and infrared telescopes. In recent times, these have been augmented by the installation of the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (GMRT) near Pune and the Himalayan Chandra Telescope (HCT) near Leh in Ladakh. Experiments have also been conducted from space platforms and by .//0 Astrosat, a multiwavelength astronomy satellite, is to be launched. With a view that the community stands to gain enormously by being part of the Virtual Observatory "23#( a national 23 initiative called Virtual Observatory-India (VO-I) has been launched. It is essentially pioneered by the IUCAA under the leadership of Ajit Kembhavi. However, for reasons not entirely clear, the initiative is yet to catch on among the community. At present, the IUCAA and IIA are the only participating research institutes. Given the fact that information technology has a very important role to play in the international 23 effort and that there is expertise in the area available in the country, VO-I in its initial phase has sought to bring together astronomers and software developers with the experience of handling large volumes of data. -

Asis Kumar Chattopadhyay Tanuka Chattopadhyay Statistical Methods for Astronomical Data Analysis Springer Series in Astrostatistics

Springer Series in Astrostatistics Asis Kumar Chattopadhyay Tanuka Chattopadhyay Statistical Methods for Astronomical Data Analysis Springer Series in Astrostatistics Editor-in-chief: Joseph M. Hilbe, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and Arizona State University, USA Jogesh Babu, The Pennsylvania State University, USA Bruce Bassett, University of Cape Town, South Africa Steffen Lauritzen, Oxford University, UK Thomas Loredo, Cornell University, USA Oleg Malkov, Moscow State University, Russia Jean-Luc Starck, CEA/Saclay, France David van Dyk, Imperial College, London, UK Springer Series in Astrostatistics, More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/1432 Springer Series in Astrostatistics Astrostatistical Challenges for the New Astronomy: ed. Joseph M. Hilbe Astrostatistics and Data Mining: ed. Luis Manuel Sarro, Laurent Eyer, William O’Mullane, Joris De Ridder Asis Kumar Chattopadhyay • Tanuka Chattopadhyay Statistical Methods for Astronomical Data Analysis 123 Asis Kumar Chattopadhyay Tanuka Chattopadhyay Department of Statistics Department of Applied Mathematics University of Calcutta University of Calcutta Calcutta, India Calcutta, India ISSN 2199-1030 ISSN 2199-1049 (electronic) ISBN 978-1-4939-1506-4 ISBN 978-1-4939-1507-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4939-1507-1 Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014945364 Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

India TMT Digest

THIRTY METER TELESCOPE A New Window to the Universe W India TMT Digest ITCC India TMT Coordination Center (ITCC) Indian Institute of Astrophysics II Block, Koramangala, Bangalore – 560034 India TMT Project Web Pages Main Site http://tmt.org/ TMT India http://tmt.iiap.res.in/ TMT Canada http://lot.astro.utoronto.ca/ TMT China http://tmt.bao.ac.cn/ TMT Japan http://tmt.mtk.nao.ac.jp/ Version III: November 2014 Credits: Smitha Subramanian, Ravinder Banyal, Eswar Reddy, Annapurni Subramaniam, G.C.Anupama, Gordon Squires, Juan C. Vargas, Tim Pyle, P.K. Mahesh, Padmakar Parihar Prasanna Deshmukh & Rosy Deblin 2 M The Background Prior to Galileo Galilei, our view of the universe was largely constrained to the unaided vision of the eyes. A mere 3-inch telescope used by him in 1608 brought a revolution in astronomy. This simple but novel instrument revealed the vastness and grandeur of the night sky which hitherto was unknown to humanity. Large telescopes (up to 10 m diameter) built in the last 20 years have led to many fascinating and intriguing discoveries in astronomy. With the advancement in technology, a tremendous progress has been made in understanding several aspects of the observable Universe. Some of the notable findings in the last few decades include the discovery of planets around other stars, irrefutable evidence for accelerating universe, indirect clues of supermassive black holes in the center of many galaxies, powerful gamma ray bursts originating from the distant corners of the Universe, existence of dark matter and dark energy, detailed identification and monitoring of asteroids and comets that could pose a serious threat to the inhabitants of the Earth and many more. -

JSPS-DST Asia Academic Seminar CPS 8Th International School of Planetary Sciences Challenges in Astronomy: Observational Advances

Joint Assembly: JSPS-DST Asia Academic Seminar CPS 8th International School of Planetary Sciences Challenges in Astronomy: Observational Advances September 26 – October 1, 2011 Minami-Awaji Royal Hotel, Hyogo, Japan Joint Assembly: JSPS-DST Asia Academic Seminar CPS 8th International School of Planetary Sciences Challenges in Astronomy: Observational Advances September 26 – October 1, 2011, Minami-Awaji Royal Hotel, Hyogo, Japan Hosted by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Indian Department of Science and Technology (DST), and Center for Planetary Science (CPS) under the MEXT Global COE Program: "Foundation of International Cen- ter for Planetary Science", a joint project between Kobe University and Hokkaido University. Organizing Committee Scientific Organizing Committee: Hiroshi Shibai (Osaka Univ., Japan) Rajaram Nityananda (TIFR, India) Ajit Kembhavi (IUCAA, India) Yoshi-Yuki Hayashi (CPS, Japan) Local Organizing Committee (*School chair, **Secretary) Hiroshi Shibai * (Osaka Univ., Japan) Misato Fukagawa (Osaka Univ., Japan) Yoshitsugu Nakagawa (CPS, Japan) Yoshi-Yuki Hayashi (CPS, Japan) Hiroshi Kimura (CPS, Japan) Ko-ichiro Sugiyama (CPS, Japan) Yoshiyuki O. Takahashi (CPS, Japan) Seiya Nishizawa (CPS, Japan) Jun Kimura (CPS, Japan) Ayako Suzuki (CPS, Japan) Takayuki Tanigawa (CPS, Japan) Ko Yamada (CPS, Japan) Akiyoshi Nouda (CPS, Japan) Asako M. Sato** (CPS, Japan) Yukiko Tsutsumino** (CPS, Japan) Mire Murakami** (CPS, Japan) Mariko Hirano** (CPS, Japan) Chieko Shishido** (CPS, Japan) Mizue Odo** (CPS, Japan) Yuki Itoh** (Osaka Univ., Japan) Joint Assembly: JSPS-DST Asia Academic Seminar CPS 8th International School of Planetary Sciences Challenges in Astronomy: Observational Advances September 26 – October 1, 2011, Minami-Awaji Royal Hotel, Hyogo, Japan Monday, 26 September, 2011 15:00 - 18:00 Registration 18:00 - 12:00 Opening Reception Tuesday, 27 September, 2011 7:30 - 8:45 <Breakfast> 8:45 - 9:00 Opening Keynote: Yushitsugu Nakagawa (CPS, Japan) 9:00 - 10:15 Lecture 1: (Chair: Yoichi Itoh) Sebastian Wolf (Univ. -

Supermassive Black Holes

Hello! Large Projects in Astronomy Opportunities and Challenges Ajit Kembhavi Current & Future Facilities for India ASTROSAT Next Decade Launched by PSLV-C30 September 28, 2015 TMT LIGO-India SKA Next 5 years ADITYA L1 Funding Agencies MHRD DST DAE ISRO UGC IIA, ARIES, RRI…Large ProjectsSpace areProgrammes, funded Research Projectsjointly bySpace DST Projects,and DAE ISRO Centres, PRL… TIFR, NCRA, IOP… Research Projects Universities, Nuclear Programme Inter-University Centres Thirty Meter Telescope Caltech University of California Canada Japan China India The Primary Mirror 492 segments, 1.44m each Area 655m2 30m equivalent hyperboloidal primary mirror, 36 segments, 492 segments, 1.44m each, 1.8m each Collecting area 655 sq m Area 76m 2 FOV 20 arcmin, 0.31 to 28 micron band pass Angular resolution with AO ~7 mas 36 Segments 492 Segments TMT 50m tall, 56m wide, 1430 tonnes moving mass of telescope, optics and instruments. TMT Segment Support Assembly Edge Sensors Actuators Simulated near-IR image of the central 17x17 arcsec of the Galaxy at TMT resolution The TMT-India Partnership Indian Institute of Astrophysics Lead Institute, TMT-India Centre Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics Aryabhata Research Institute of Observational Sciences Other Research Institutes University Departments India-TMT role in the project Eswar Reddy Emphasis was given to WPs whose knowhow could directly help to take-up projects such as 10-12-m within the country. M1 polishing M1 Control system .Actuators .Edge Sensors .Electronics Segment Support Assembly (SSAs) Mirror Coating: Control Software Instrument Development – IRMS TMT science Center-under proposal LIGO India Direct Detection of Gravitational Waves The Binary Pulsar 1913+16 Hulse & Taylor 1974 Orbital decay due to the emission of gravitational waves Principles of Detection 20 T. -

Indian Institute of Astrophysics

INDIAN INSTITUTE OF ASTROPHYSICS ACADEMIC REPORT 2006–07 EDITED BY : S. K. SAHA EDITORIAL ASSISTANCE : SANDRA RAJIVA Front Cover : High Altitude Gamma Ray (HAGAR) Telescope Array Back Cover (outer) : A collage of various telescopes at IIA field stations Back Cover (inner) : Participants of the second in-house meeting held at IIA, Bangalore Printed at : Vykat Prints Pvt. Ltd., Airport Road Cross, Bangalore 560 017 CONTENTS Governing Council 4. Experimental Astronomy 35 Honorary Fellows 4.1 High resolution astronomy 35 The year in review 4.2 Space astronomy 36 1. Sun and solar systems 1 4.3 Laboratory physics 37 1.1 Solar physics 1 5. Telescopes and Observatories 39 1.2 Solar radio astronomy 8 5.1 Kodaikanal Observatory 39 1.3 Planetary sciences 9 5.2 Vainu Bappu Observatory, Kavalur 39 1.4 Solar-terrestrial relationship 10 5.3 Indian Astronomical Observatory, 2. Stellar and Galactic Astronomy 12 Hanle 40 2.1 Star formation 12 5.4 CREST, Hosakote 43 2.2 Young stellar objects 12 5.5 Radio Telescope, Gauribidanur 43 2.3 Hydrogen deficient stars 13 6. Activities at the Bangalore Campus 45 2.4 Fluorine in evolved stars 14 6.1 Electronics laboratory 45 2.5 Stellar parameters 15 6.2 Photonics laboratory 46 2.6 Cepheids 15 6.3 Mechanical engineering division 47 2.7 Metal-poor stars 16 6.4 Civil engineering division 47 2.8 Stellar survey 16 6.5 Computer centre 47 2.9 Binary system 17 6.6 Library 47 2.10 Star cluster 17 7. Board of Graduate Studies 49 2.11 ISM 18 8.