Keats' "Ode to a Nightingale": a Poem in Stages with Themes of Creativity, Escape and Immortality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representation of Natural World in Keats‟S “Ode to a Nightingale”

International Journal of Engineering Applied Sciences and Technology, 2019 Vol. 3, Issue 11, ISSN No. 2455-2143, Pages 53-61 Published Online March 2019 in IJEAST (http://www.ijeast.com) REPRESENTATION OF NATURAL WORLD IN KEATS‟S “ODE TO A NIGHTINGALE” Lok Raj Sharma Associate Professor of English Head of Faculty of Education Makawanpur Multiple Campus, Hetauda, Nepal Abstract - The prime objective of this article Nature carries a great symbolic significance is to explore the representations of the natural in creative writings. world as presented in one of the famous odes “Ode to a Nightingale" is a romantic poem of Keats‟s “Ode to a Nightingale” published composed by John Keats (1795-1821), who in 1819. This paper seeks to analyze this ode was a great romantic poet. “Ode to a from the Ecocritical Perspective which deals Nightingale" is one of the most highly with the study of man's relationships with his admired regular odes in English literature. It physical environment along with his reveals Keats's keen imaginative faculty, perception and conception of it. This article heightened sensibility and those aesthetic concludes that nature plays a very prominent qualities for which Keats is much well- role to generate sheer pleasure in man. The known. He was one of the greatest lovers and nature is represented as an active force, admirers of nature. His love of nature was whereas persons are represented as positively solely sumptuous and he cherished the beneficialized entities. This article is expected gorgeous sights and scenes of nature. to be significant to those who are involved in The article writer has attempted to teaching and learning ecocriticism. -

The Song of Keats's Nightingale

The Oswald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English Volume 10 | Issue 1 Article 3 2008 Catalyst and Inhibitor: The onS g of Keats’s Nightingale Jonathan Krol John Carroll University University Heights, Ohio Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/tor Part of the Literature in English, Anglophone outside British Isles and North America Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Krol, Jonathan (2008) "Catalyst and Inhibitor: The onS g of Keats’s Nightingale," The Oswald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/tor/vol10/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you by the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The sO wald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Catalyst and Inhibitor: The onS g of Keats’s Nightingale Keywords John Keats, Ode to a Nightingale, Romantic Era literature This article is available in The sO wald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/tor/vol10/iss1/3 1 Catalyst and Inhibitor: The Song of Keats’s Nightingale Jonathan Krol John Carroll University University Heights, Ohio n his poem “Ode to a Nightingale,” John Keats Idemonstrates a desire to leave the earthly world behind in hopes of unifying with the elusive bird in a fleeting, fantastical world. -

Dialogical Odes by John Keats: Mythologically Revisited

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 4, No. 8, pp. 1730-1734, August 2014 © 2014 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.4.8.1730-1734 Dialogical Odes by John Keats: Mythologically Revisited Somayyeh Hashemi Department of English, Tabriz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz, Iran Bahram Kazemian Department of English, Tabriz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz, Iran Abstract—This paper, using Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory of dialogism tries to investigate the indications of dialogic voice in Odes by John Keats. Indeed this study goes through the dialogic reading of ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’, ‘Ode to Psyche’, and ‘Ode on Melancholy’, considering mythological outlooks. Analyzing Keats’s odes through dialogical perspective may reveal that Keats plays a role of an involved and social poet of his own time. Moreover, Keats embraces the world of fancy and imagination to free himself from sufferings of his society. Keats’ odes are influenced by expression of pain-joy reality by which he builds up a dialogue with readers trying to display his own political and social engagement. Applying various kinds of mythological elements and figures within the odes may disclose Keats’s historical response and reaction toward a conflicted society and human grieves in general. Index Terms—Bakhtinian dialogism, Keats’ Odes, pain, pleasure, mythology I. INTRODUCTION John Keats as one of the major poets of Romanticism, composed multiple popular poems and his odes gained the most attention of them. Going through his odes, it appears to the reader that Keats attempts to deal with different interpretation of pain and pleasure concepts. -

John Keats 1 John Keats

John Keats 1 John Keats John Keats Portrait of John Keats by William Hilton. National Portrait Gallery, London Born 31 October 1795 Moorgate, London, England Died 23 February 1821 (aged 25) Rome, Italy Occupation Poet Alma mater King's College London Literary movement Romanticism John Keats (/ˈkiːts/; 31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English Romantic poet. He was one of the main figures of the second generation of Romantic poets along with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, despite his work only having been in publication for four years before his death.[1] Although his poems were not generally well received by critics during his life, his reputation grew after his death, so that by the end of the 19th century he had become one of the most beloved of all English poets. He had a significant influence on a diverse range of poets and writers. Jorge Luis Borges stated that his first encounter with Keats was the most significant literary experience of his life.[2] The poetry of Keats is characterised by sensual imagery, most notably in the series of odes. Today his poems and letters are some of the most popular and most analysed in English literature. Biography Early life John Keats was born in Moorgate, London, on 31 October 1795, to Thomas and Frances Jennings Keats. There is no clear evidence of his exact birthplace.[3] Although Keats and his family seem to have marked his birthday on 29 October, baptism records give the date as the 31st.[4] He was the eldest of four surviving children; his younger siblings were George (1797–1841), Thomas (1799–1818), and Frances Mary "Fanny" (1803–1889) who eventually married Spanish author Valentín Llanos Gutiérrez.[5] Another son was lost in infancy. -

236201457.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE ź ±·±± ź ɷ˂ʎɁŽ í ù ± ¸ ± ¹ ô å í ð å ò žɥɔȣȶȹª Ode on Indolence ᝲ ᴥȰɁ̝ᴦ ࠞюඩˢ ᴥ੪Ұᴦ ᴥ˧ᴦ ˹Ode on Indolence ఊጶᣵɂǾႆȁȪȗͶȻԇȪȲ˧ᐐɥѓɆЫɁ۫Ɂ ȾߨȫȦɔɞǾমᰅᇒȗɁᠲɥ࢛ɆȹȗɞǿͽֿȾўȨɟȲɁᐥբᴥŽÔèåù ôïéì îïô¬ îåéôèåò äï ôèåù óðéᴦɂǾȦɁЕࣻɥӎɋ߳Ȣ឴ቺȻɕțɞǿ Óï¬ ùå ôèòåå çèïóôó¬ áäéåõ¡ Ùå ãáîîïô òáéóå Íù èåáä ãïïìâåääåä éî ôèå æìï÷åòù çòáóó» Æïò É ÷ïõìä îïô âå äéåôåä ÷éôè ðòáéóå¬ Á ðåôìáíâ éî á óåîôéíåîôáì æáòãå¡ Æáäå óïæôìù æòïí íù åùåó¬ áîä âå ïîãå íïòå Éî íáóñõåìéëå æéçõòåó ïî ôèå äòåáíù õòî» Æáòå÷åìì¡ É ùåô èáöå öéóéïîó æïò ôèå îéçèô¬ Áîä æïò ôèå äáù æáéîô öéóéïîó ôèåòå éó óôïòå» Öáîéóè¬ ùå ðèáîôïíó¬ æòïí íù éäìå óðòéçèô¬ Éîôï ôèå ãìïõäó¬ áîä îåöåò íïòå òåôõòî¡ ¨Ode on Indolence¬ì쮵±¶°© ᴥ±ᴦ ź ±·±² ź Ȉ˧̷Ɂ̪ȉɥ۫ȾᩐȫȦɔɞᚐའɂǾ˧ᐐɥȈɮʽʓʶʽʃɁȉᴥì® ±¶º ŽÔèå âìéóóæõì ãìïõä ïæ óõííåòéîäïìåîãåž» ì® ¶°ºŽôèå ãìïõäóžᴦȺӿɒᣅ ɒǾፅɔɞȦȻȺɕȕɞǿȦɁ Ode on Indolence Ɂɸʴʁɬ᭛Ɂ۫ᴥì® µº ᴻȻȪȹ۫ట఼ۃŽá íáòâìå õòîžᴦɂǾ˧ᐐɥᖃɞᴹᯏ۫ᴻȕɞȗɂᴹ ɁमҾɥȲȬȦȻȾȽɞǿ²± ȦȦȺǾɸʴʁɬ᭛Ɂ۫Ⱦ૫ȞɟȲ̷࿎ЅȻȗ șպሗɁɮʫ˂ʂɥႊȗɞ OdeonaGrecianUrnȻ Ode on Indolence ȻɁ ᩖɁ᪨ȳȶȲᄾᤏཟȾႡȪȲȗǿҰᐐȾȝȗȹɂǾᝂ̷ɂЅӌɥႊȗȹ۫ Ɂ̷࿎ɥႆᐐȨȽȟɜᅓҰȾ֣ɆҋȪǾयɜɁ˰ႜɋɁՎоɥ᭐șǿȳȟǾ˨ ऻᐐȺɂǾᝂ̷ᴥɁျॴᴦɂᅓҰȾးɟҋȲ̷࿎ȻɁպԇɥઑɒǾ˧ᐐɥѯȲ ȗᆀɁधЅȻȪȹᖃɝՍɠșȻȬɞǿOde on a Grecian Urn Ɂᝂ̷ɁᝁɒɂǾ ᄠᐼȽȦȻȾǾ̷࿎ȲȴȟЫɁᆀɁ˰ႜȾᣝԵȬɞȦȻȺ༆țȹȪɑșᴥìì® ´´´µºŽÔèïõ¬ óéìåîô æïòí¬ äïóô ôåáóå õó ïõô ïæ ôèïõçèô ¯ Áó äïôè åôåòîéôùº Ãïìä Ðáóôïòáì¡žᴦǿȦɟȾߦȪȹǾ˧ᐐɥ۫˨ɋᣜȗᣌȰșȻȬɞ Ode on ઔȽমᰅᇒȗɁᕹȾɕȞȞɢɜȭᴥìì® µ¹ږIndolence Ɂᝂ̷Ɂ᭐ȗɂǾयɁ ¶°ºŽÖáîéóè¬ ùå ðèáîôïíó¬ æòïí íù éäìå óðòéçèô¬ ¯ Éîôï ôèå ãìïõäó¬ áîä îåöåò íïòå òåôõòî¡žᴦǾȰșዊԨȾկțɜɟȰșȾɂțȽȗǿ²² ȽȯȽɜǾ ᝂ̷ɂ˧ᐐɋɁȪȟȲȗঢ়ᅔȾસțɜɟȹɕȗɞȞɜȺȕɞᴥìì® ³³³´ -

Ode to a Clothes Peg It Hasn't Evolved Much from the Humble Forked Twig

Ode to a Clothes Peg It hasn’t evolved much from the humble forked twig or a single finger of pine whittled into a split pin that gripped britches and bloomers between its loins to the pair of lightweight plastic opposable thumbs hinged by a fusewire spring, or the toothless baby croc that bites down on a nylon washing line. I’m staging this thought at the rotary dryer trying to conjure Keats, wondering whether he offered his small hands to the salty ropes or coughed stipples of blood on the white sail while the brig’s bowsprit needled for Rome. The pegs in this peg-bag (stitched in the shape of a saucy scullery maid) were handed down like the bony relics of women saints and I’ll guess have never been touched by a man until now; mouthy car-horns summoned a terrace of wives to their doors and out they came, flustered and vexed, extending the wooden props, masting clean sheets into the April air so husbands and feckless sons could nose their Ford Cortinas along the street. The wide afternoon skies were pinned with clouds the colour and shape of death masks and shrouds. Simon Armitage Written to commemorate the bicentenary of the composition of John Keats’ six famous odes, Ode to Psyche, Ode to a Nightingale, Ode on a Grecian Urn, Ode on Melancholy, Ode on Indolence, and To Autumn. Among his greatest works, the poems are also some of the most famous in the English Language. . -

THE RELATION BETWEEN HUMAN and NATURE in JOHN Keats' Odes

The relation between human and nature in John KeatS’ oDeS: an expReSSive StuDy Agung Nalendra Janiswara Christinawati ABSTRACT This study attempts to discuss the relation between human and nature in John Keats’ Odes as the representation of Keats’ awareness in nature and the changing of nature in the era of industrialization, especially in England. This study will discuss three odes, “Ode to a Nightingale”, “Ode to Psyche”, and “To Autumn” released during the English Romantic Period. The main concern of this study is to analyze Keats’ awareness of nature and the relation between human and nature which presented in these three odes written by John Keats. To analyze the topic of discussion, this study applies Expressive theory suggested by Abrams. This study finds out that Keats expresses nature as the source and the core of this world. He emphasizes that the nature must be protected and conserved to sustain human’s life and also the world. This relation between human and nature affects Keats in writing his odes as the portrayal of his feeling toward nature and social condition in his period. Keywords: Awareness; Industrialization; Nature; Ode; Environment; World 1. Introduction The beauty of nature is a very special theme in English Romantic period, when nature was neglected by people because of industrialization. John Keats brought different perspective about beauty in his odes. It is assumed that this study portrays the condition of human and nature that is affected by industrialization and disappearance of the nature as the important part of life in this world. John Keats brings his odes to the reader and society to remind that the environment is very important for human being. -

This Essay Takes As Its Basis Four Odes by John Keats and Treats Them As A

“BURSTING JOY’S GRAPE” IN KEATS’ ODES DANIEL BRASS This essay takes as its basis four odes by John Keats and treats them as a sequence of poems in which he develops, discusses and elaborates the themes of permanence and transience, both at the level of an individual human life and in a larger, transgenerational, cosmic view of time. Underlying the four poems – “Ode on a Grecian Urn”, “Ode on Melancholy”, “To Autumn” and “Ode to a Nightingale” – is the idea of fullness or satisfaction, an intense climax of experience preceding the melancholia that inevitably attends the decline from such a heightened moment of experience. The pattern, I suggest, is founded on the sexual experience: increasing excitement and stimulation leading to a climax followed by a post-coital decline which Keats describes in various guises in each of the poems. In addition to this appearance of the orgasm in their structure, sexual imagery is prevalent throughout the odes. While the deployment of devices and images in poetry may be a deliberate choice on the poet’s part, analysis of a collection of works by an author reveals underlying structural features that recur throughout the work. The orgasm is one such feature prominent in Keats’ imagination. Individual sexual images may be intentional, but the structure of the odes points to a less overt occurrence of these sexual structures. Keats wrote the four odes I will be considering during 1818, the year after he met Fanny Brawne, with whom he immediately fell in love. Moreover, some critics have suggested it was during this time that Keats became aware that he was suffering from tuberculosis and that he would not live very much longer.1 Biographical interpretation of these poems does not, in itself, offer much insight into them, but Keats’ emotional life and his experience of illness must have influenced his psyche and may have produced the fascination with questions of presence and absence, 1 Don Colburn, “A Feeling for Light and Shade: John Keats and His ‘Ode to a Nightingale’”, Gettysburg Review, 5 (1992), 217. -

A Discussion of John Keats's Ode to a Nightingale

A DISCUSSION OF JOHN KEATS’S ODE TO A NIGHTINGALE Kul Bahadur Khadka * Abstract John Keats passes away at an early age but leaves many outstanding works behind. In his Ode to a Nightingale, the poet sees suffering on the earth and highly appreciates a nightingale’s marvelous music. This article discusses the pain - pleasure contrast and association in terms of the poet and the nightingale. It also explores the use of time and space in the poem. It is important to know where and when the bird is singing and the poet is sitting, listening to the bird’s music. The use of imagery ad symbols in the poem is very significant to connect the poet’s world with that of the bird. Art, death and life can be drawn as major themes in the poem. In order to strengthen the discussion, various books and critics’ opinions concerning Keats, the respective poe m and Romanticism have been consulted. The discussion reveals the poet’s ugly and painful world which is real and the nightingale’s beautiful and pleasurable world which is ideal. The real contrasts from the ideal and sometimes they get associated with eac h other. In exclusion of the ideal, the real suffers and gets confused. Keywords: negative capability, setting, theme, symbols and imagery, real and ideal. John Keats, a renowned poet of the second - generation Romantic poets, was born in London in 1795. H is father, a head hostler at a London livery stable, had four children - three sons (John, the first - born) and a daughter. -

Appendix a Selection of Poems Written to Or About John Keats: 1821-1994

Appendix A Selection of Poems written to or about John Keats: 1821-1994 CONTENTS OF APPEND LX The following poems are present in rough chronological order of publica tion or composition, beginning with Clare (1821). 'To the Memory of John Keats,' John Clare. 167 'ln Memory of Keats,' S. Laman Blanchard. 167 'Written in Keats's 'Endymion',' Thomas Hood. 168 'On Keats,' Christina Rossetti. 168 'From Aurora Leigh,' Elizabeth Barrett Browning. 169 'Popularity,' Robert Browning. 170 'To the Spirit of Keats,' james Russell Lowell. 171 'On Keats's Grave,' Alice Meynell. 172 ' Keats,' Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. 174 'The Grave of Keats,' Oscar Wilde. 174 'John Keats,' Dante Gabriel Rossetti. 175 'Post Mortem,' A. C. Swinburne. 175 'Keats' Critics,' Perry Marshall. 177 'To Keats,' Lord Dunsany. 177 'To a Life Mask of Keats,' Anne Elizabeth Wilson. 178 'On the Drawing Depicting John Keats in Death,' Rainer Maria Rilke (trans. J. B. Leishman). 178 'To Keats,' Louise Morgan Sill. 179 'A Brown Aesthete Speaks,' Mae V. Cowdery. 180 'ln an Auction Room,' Christopher Morley. 181 'In Remembrance of the Ode to a Nightingale,' Katherine Shepard Hayden. 182 'On Reading Keats in War Time,' Karl Shapiro. From V-Letter and Other Poems. New York: Reyna! & Hitchcock, 1944. 182 'A Room in Rome,' Karl Shapiro. New Rochelle, NY: James L. Weil, 1987. 183 'Posthumous Keats,' Stanley Plumly. From Summer Celestin/. New York: Ecco Press, 1983. 184 166 Appendix: A Selection of Poems 167 'Scirocco,' Jorie Graham. From Erosion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983. 185 'John Keats at the Low Wood Hotel Disco, Windermere,' Peter Laver. -

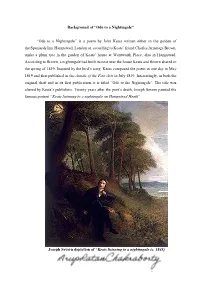

Background of “Ode to a Nightingale” “Ode to a Nightingale” Is a Poem By

Background of “Ode to a Nightingale” “Ode to a Nightingale” is a poem by John Keats written either in the garden of the Spaniards Inn, Hampstead, London or, according to Keats’ friend Charles Armitage Brown, under a plum tree in the garden of Keats’ house at Wentworth Place, also in Hampstead. According to Brown, a nightingale had built its nest near the house Keats and Brown shared in the spring of 1819. Inspired by the bird’s song, Keats composed the poem in one day in May 1819 and first published in the Annals of the Fine Arts in July 1819. Interestingly, in both the original draft and in its first publication, it is titled “Ode to the Nightingale”. The title was altered by Keats’s publishers. Twenty years after the poet’s death, Joseph Severn painted the famous portrait “Keats listening to a nightingale on Hampstead Heath”. Joseph Severn depiction of “Keats listening to a nightingale (c. 1845) Critics generally agree that Nightingale was the second of the five ‘great odes’ of 1819 and its themes are reflected in its ‘twin’ ode, ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’. Of Keats’s major odes of 1819, “Ode to Psyche”, was probably written first and “To Autumn” written last. It is possible that “Ode to a Nightingale” was written between 26 April and 18 May 1819, based on weather conditions and similarities between images in the poem and those in a letter sent to Fanny Keats on May Day. Keats’s friend and roommate, Charles Armitage Brown, described the composition of this beautiful work as follows: “In the spring of 1819 a nightingale had built her nest near my house. -

Escapism, Oblivion, and Process in the Poetry of Charlotte Smith and John Keats

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 5-2013 Escapism, Oblivion, and Process in the Poetry of Charlotte Smith and John Keats. Jessica Hall East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hall, Jessica, "Escapism, Oblivion, and Process in the Poetry of Charlotte Smith and John Keats." (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 62. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/62 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Escapism, Oblivion, and Process in the Poetry of Charlotte Smith and John Keats Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of Honors By Jessica Hall The Honors College Midway Honors Program East Tennessee State University April 12, 2013 _____________________________ Dr. Jesse Graves, Faculty Mentor Hall 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………. 3 CHAPTER ONE……………………………………………………………………… 5 CHAPTER TWO……………………………………………………………………… 18 CHAPTER THREE…………………………………………………………………… 45 CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………………... 55 WORKS CITED………………………………………………………………………. 57 Hall 3 Introduction Charlotte Turner Smith and John Keats have not often been considered together; on those occasions that they have, it has been in the most peripheral and narrow ways. There is ample cause for this deficiency in critical comment. Smith and Keats wrote, in many respects, from opposite ends of the Romantic spectrum. In her immensely popular Elegiac Sonnets, Smith— sometimes lauded as the first British Romantic poet—perfected the prototype of the ode form M.H.