Changing Characteristics of Villages in Tamil Nadu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

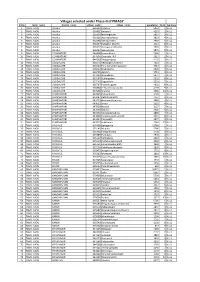

Villages Selected Under Phase-II of PMAGY

Villages selected under Phase-II of PMAGY Sl No State_name District_name village_code village_name population Rank Ispmagy 1 TAMIL NADU Ariyalur 636312 Kulumur 5052 1 NULL 2 TAMIL NADU Ariyalur 636451 Pottaveli 4261 2 NULL 3 TAMIL NADU Ariyalur 636319 Namangunam 3897 3 NULL 4 TAMIL NADU Ariyalur 636311 Ayanathathanur 3823 4 NULL 5 TAMIL NADU Ariyalur 636368 Vethiyarvettu 3503 5 NULL 6 TAMIL NADU Ariyalur 636357 Kattathur (North) 2113 6 NULL 7 TAMIL NADU Ariyalur 636372 Kattagaram (South) 2093 7 NULL 8 TAMIL NADU Ariyalur 636453 Sennivanam 1870 8 NULL 9 TAMIL NADU COIMBATORE 644408 Kanuvakkarai 2646 1 NULL 10 TAMIL NADU COIMBATORE 644876 Anamalai R.F. 2014 2 NULL 11 TAMIL NADU COIMBATORE 644530 Thoppampatti 1135 3 NULL 12 TAMIL NADU CUDDALORE 636574 Veerapperumanallur 7324 1 NULL 13 TAMIL NADU CUDDALORE 636544 Perumalnaickenpalayam 7317 2 NULL 14 TAMIL NADU CUDDALORE 636622 Madalpattu 6028 3 NULL 15 TAMIL NADU CUDDALORE 636705 Agaram 5715 4 NULL 16 TAMIL NADU CUDDALORE 637229 Sirupakkam 5477 5 NULL 17 TAMIL NADU CUDDALORE 637167 U.Mangalam 5292 6 NULL 18 TAMIL NADU CUDDALORE 637103 Seppakkam 5201 7 NULL 19 TAMIL NADU CUDDALORE 636707 Puvanikuppam 4992 8 NULL 20 TAMIL NADU CUDDALORE 636860 C.Thandeswaranallur 4159 9 NULL 21 TAMIL NADU CUDDALORE 637238 Orangur 3966 10 NULL 22 TAMIL NADU DHARMAPURI 643335 Palayampalli 4195 1 NULL 23 TAMIL NADU DHARMAPURI 643487 Pethathampatti 4137 2 NULL 24 TAMIL NADU DHARMAPURI 643223 Hanumanthapuram 3940 3 NULL 25 TAMIL NADU DHARMAPURI 643613 Sivadi 3532 4 NULL 26 TAMIL NADU DHARMAPURI 643329 Navalai 3127 -

VIRUDHUNAGAR DISTRICT Minerals and Mining Irrigation Practices

VIRUDHUNAGAR DISTRICT Virudhunagar district has no access to sea as it is covered by land on all the sides. It is surrounded by Madurai on the north, by Sivaganga on the north-east, by Ramanathapuram on the east and by the districts of Tirunelveli and Tuticorin on the south. Virudhunagar District occupies an area of 4288 km² and has a population of 1,751,548 (as of 2001). The Head-Quarters of the district Virudhunagar is located at the latitude of 9N36 and 77E58 longitude. Contrary to the popular saying that 'Virudhunagar produces nothing, but controls everything', Virudhunagar does produce a variety of things ranging from edible oil to plastic-wares. Sivakasi known as 'Little Japan' for its bustling activities in the cracker industry is located in this district. Virudhunagar was a part of Tirunelveli district before 1910, after which it became a part of Ramanathapuram district. After being grafted out as a separate district during 1985, today it has eight taluks under its wings namely Aruppukkottai, Kariapatti, Rajapalayam, Sattur, Sivakasi, Srivilliputur, Tiruchuli and Virudhunagar. The fertility of the land is low in Virudhunagar district, so crops like cotton, pulses, oilseeds and millets are mainly grown in the district. It is rich in minerals like limestone, sand, clay, gypsum and granite. Tourists from various places come to visit Bhuminathaswamy Temple, Ramana Maharishi Ashram, Kamaraj's House, Andal, Vadabadrasayi koi, Shenbagathope Grizelled Squirrel Sanctuary, Pallimadam, Arul Migu Thirumeni Nadha Swamy Temple, Aruppukkottai Town, Tiruthangal, Vembakottai, Pilavakkal Dam, Ayyanar falls, Mariamman Koil situated in the district of Virudhunagar. Minerals and Mining The District consists of red loam, red clay loam, red sand, black clay and black loam in large areas with extents of black and sand cotton soil found in Sattur and Aruppukottai taluks. -

Sivagangai Temperature Over Sivaganga for the Periods 2010- 2

DISTRICT WISE CLIMATE CHANGE INFORMATION FOR THE STATE OF TAMIL NADU TEMPERATURE PROJECTIONS FOR SIVAGANGA 1. 27.1 About Sivaganga The geographical position of Sivaganga district is between 9°32' and 10°18' North latitude and between 78°08' and 79°01' East longitude. It is bounded by Madurai district to the west, Fig 27.1 Changes in Max. Temperature for 2020s, 2050s & 2080s Pudukkottai district and Tiruchirappalli district to the north and Ramanathapuram district to the south. Sivaganga district occupies an area of approximately 4189 sq. km. Its in the 95 meters to 1,2,3 106 meters elevation range. Fig 27.2 Changes in Min. Temperature for 2020s, 2050s & 2080s 2. 27.2 Climate of Sivaganga Table 27.1 Changes in Temperature Parameter 2020s 2050s 2080s The district enjoys a tropical climate. The period from April to June is generally hot and dry. The Maximum Temperature +1.1°C +2.1°C +3.1°C district’s highest day temperature in summer is Minimum Temperature +1.2°C +2.4°C +3.6°C between 30°C to 36°C .Average temperatures of 27.4 Key Findings January is 26°C, February is 27°C, March is 28°C, The average change of maximum and minimum 2,3 April is 30°C, May is 32°C. temperature for Sivaganga district are expected to increase by 3.1°C and 3.6°C respectively by the end 27.3 Temperature Projections for Sivaganga of the century. The annual maximum and minimum temperature 27.5 References normal (1970-2000) of the district are 33.7°C and 22.8°C respectively.4 Projections of maximum 1. -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2013 [Price: Rs. 54.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 41] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2013 Aippasi 6, Vijaya, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2044 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 2893-3026 Notice .. 3026-3028 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 43888. My son, D. Ramkumar, born on 21st October 1997 43891. My son, S. Antony Thommai Anslam, born on (native district: Madurai), residing at No. 4/81C, Lakshmi 20th March 1999 (native district: Thoothukkudi), residing at Mill, West Colony, Kovilpatti, Thoothukkudi-628 502, shall Old No. 91/2, New No. 122, S.S. Manickapuram, Thoothukkudi henceforth be known as D. RAAMKUMAR. Town and Taluk, Thoothukkudi-628 001, shall henceforth be G. DHAMODARACHAMY. known as S. ANSLAM. Thoothukkudi, 7th October 2013. (Father.) M. v¯ð¡. Thoothukkudi, 7th October 2013. (Father.) 43889. I, S. Salma Banu, wife of Thiru S. Shahul Hameed, born on 13th September 1975 (native district: Mumbai), 43892. My son, G. Sanjay Somasundaram, born residing at No. 184/16, North Car Street, on 4th July 1997 (native district: Theni), residing Vickiramasingapuram, Tirunelveli-627 425, shall henceforth at No. 1/190-1, Vasu Nagar 1st Street, Bank be known as S SALMA. -

Namakkal - 637 304

Size : 8 x 20 cm City Union Bank Limited Credit Recovery and Management Department Administrative Office : No. 24-B, Gandhi Nagar, Kumbakonam - 612 001. E-Mail id : [email protected], Ph : 0435-2432322, Fax : 0435-2431746 RE-TENDER-CUM-AUCTION SALE NOTICE UNDER SARFAESI ACT 2002 The following property/ies mortgaged to City Union Bank Limited will be sold in Re-Tender- cum-Public Auction by the Authorised Officer of the Bank, under Rule 8 (6) & 9 of the Security Interest (Enforcement) Rules, 2002, under the SARFAESI Act, 2002, for recovery of a sum of Rs.23,88,444/- (Rupees Twenty Three Lakh Eighty Eight Thousand Four Hundred and Forty Four Only) as on 19-11-2020 together with further interest to be charged from 20-11-2020 onwards and other expenses, any other dues to the Bank by the borrowers / guarantors No.1) M/s. Sri Venkateswara Steels, Door No.3/217E, Ammaiyarkadu, Kudhiraipallam, Karuveppampatti, Tiruchengode, Namakkal - 637 304. No.2) Mr. P. Murugesan, S/o. Palani, No.2/242(2), Arunthathiyar Street, Kovilpalayam, Sathinaickenpalayam, Tiruchengode, Nammakal District - 637 205. No.3) Mrs. M. Kuppayee, W/o. P. Murugesan, No.2/242(2), Arunthathiyar Street, Kovilpalayam, Sathinaickenpalayam, Tiruchengode, Nammakal District - 637 205. Immovable Property Mortgaged to our Bank (Property Owned by P. Murugesan, S/o. Palani) Namakkal Registration District and Tiruchengode Sub-Registration District, Tiruchengode Taluk, Sathinaickenpalayam Group of Kovilpalayam Village, S.No.10/1, Plot Nos.58, 59 & 60 with Total extent of 3,157½ Sq.ft. of Land.Measurement: East to West (on Northern side) 109½ feet, East to West (on Southern side) 101 feet, South to North ( on both East and West side) 30 feet. -

Address STD CODE Phone No Fax No E-Mail Address 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT 2005 NAME AND ADDRESS OF ASSISTANT PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICERS AND PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICERS - COMMERCIAL TAXES DEPT. Assistant Public Sl.No. Name of the Office Information Officer/Public Address STD CODE Phone No Fax No E-Mail Address Information Officer Deputy Commissioner Office of the Commissioner of Commercial Commissioner of Commercial 28546944,28514656 1 (Special Cell) Public Taxes, Chepauk, Ezhilagam Complex, Chennai 044 Taxes Extn .29 Information Officer 600 005. Asst.Commissioner (General Office of the Commissioner of Commercial 28546944, 28514656 Services) Assistant Public Taxes, Chepauk, Ezhilagam Complex, Chennai 044 Extn .25 Information Officer 600 005. Asst.Commissioner (Public Office of the Commissioner of Commercial 28546944,28514656 Relations)/ Assistant Public Taxes, Chepauk, Ezhilagam Complex, Chennai 044 Extn .44 Information Officer 600 005. Personal Asst. to Joint Office of the Joint Commissioner (Commercial Joint Commissioner,Chennai( 2 Commissioner, Chennai rd 044 28295551, 28294396 North ) Taxes) Chennai (North) 3 Floor PAPJM (North)/ PIO Buildings, No. 1 Greams Road, Chennai -6 Office of the Assistant Commissioner (CT) Zone- Asst.Commissioner, Zone - I 3 Asst. Commissioner - Zone - I rd 044 28295695 -- -- /PIO 1 3 Floor PAPJM Buildings, No. 1 Greams Road, Chennai -6 Office of the Commercial Tax Officer, Harbour I Commercial Tax Officer, CTO, Harbour - I Assessment Circle, Dass India Tower 044 25248777 - - Harbour - I /PIO Building,No.3,2nd Lane Beach,Chennai-1 Office of the Commercial -

Community List

ANNEXURE - III LIST OF COMMUNITIES I. SCHEDULED TRIB ES II. SCHEDULED CASTES Code Code No. No. 1 Adiyan 2 Adi Dravida 2 Aranadan 3 Adi Karnataka 3 Eravallan 4 Ajila 4 Irular 6 Ayyanavar (in Kanyakumari District and 5 Kadar Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 6 Kammara (excluding Kanyakumari District and 7 Baira Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 8 Bakuda 7 Kanikaran, Kanikkar (in Kanyakumari District 9 Bandi and Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Bellara 8 Kaniyan, Kanyan 11 Bharatar (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 9 Kattunayakan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Kochu Velan 13 Chalavadi 11 Konda Kapus 14 Chamar, Muchi 12 Kondareddis 15 Chandala 13 Koraga 16 Cheruman 14 Kota (excluding Kanyakumari District and 17 Devendrakulathan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 18 Dom, Dombara, Paidi, Pano 15 Kudiya, Melakudi 19 Domban 16 Kurichchan 20 Godagali 17 Kurumbas (in the Nilgiris District) 21 Godda 18 Kurumans 22 Gosangi 19 Maha Malasar 23 Holeya 20 Malai Arayan 24 Jaggali 21 Malai Pandaram 25 Jambuvulu 22 Malai Vedan 26 Kadaiyan 23 Malakkuravan 27 Kakkalan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 24 Malasar Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 25 Malayali (in Dharmapuri, North Arcot, 28 Kalladi Pudukkottai, Salem, South Arcot and 29 Kanakkan, Padanna (in the Nilgiris District) Tiruchirapalli Districts) 30 Karimpalan 26 Malayakandi 31 Kavara (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 27 Mannan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 28 Mudugar, Muduvan 32 Koliyan 29 Muthuvan 33 Koosa 30 Pallayan 34 Kootan, Koodan (in Kanyakumari District and 31 Palliyan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 32 Palliyar 35 Kudumban 33 Paniyan 36 Kuravan, Sidhanar 34 Sholaga 39 Maila 35 Toda (excluding Kanyakumari District and 40 Mala Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 41 Mannan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 36 Uraly Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 42 Mavilan 43 Moger 44 Mundala 45 Nalakeyava Code III (A). -

Extension of EOI Submission

Tamil Nadu Urban Finance and Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (A Government of Tamil Nadu Undertaking) No.490/1-2, Anna Salai, Nandanam, Chennai – 600 035 Phone No: 044-24329800, 24329801 Fax: 044 – 24350814 E-mail: [email protected] Extension of EOI Submission Dated: 16.04.2018 Extension of below listed EOI Submission for Smart Elements implementation in 10 Smart Cities of Tamil Nadu. Last date for EOI Submission: 30th April 2018 Item Request for Expression of Interest Ref No. Expression of Interest for Wifi-Hotspots across 10 Smart Cities (Coimbatore, Madurai, Salem, TUFIDCO/CCC- 1 Thanjavur, Tiruchirapalli, Vellore, Tirunelveli, WIFI/1240/AM(M)/2018 Tiruppur, Thoothukudi and Erode) of Tamil Nadu Expression of Interest for Smart Class Rooms in 10 Smart Cities (Coimbatore, Madurai, Salem, TUFIDCO/CCC- 2 Thanjavur, Tiruchirapalli, Vellore, Tirunelveli, SCR/1241/AM(M)/2018 Tiruppur, Thoothukudi and Erode) of Tamil Nadu Expression of Interest for Variable Message Display TUFIDCO/CCC- in 10 Smart Cities (Coimbatore, Madurai, Salem, 3 VMDS/1242/AM(M)/2018 Thanjavur, Tiruchirapalli, Vellore, Tirunelveli, Tiruppur, Thoothukudi and Erode) of Tamil Nadu Expression of Interest for Water Supply SCADA Implementation in 10 Smart Cities (Coimbatore, TUFIDCO/CCC-WS- 4 Madurai, Salem, Thanjavur, Tiruchirapalli, Vellore, SC/1243/AM(M)/2018 Tirunelveli, Tiruppur, Thoothukudi and Erode) of Tamil Nadu Expression of Interest for Environmental Sensors Implementation in 10 Smart Cities (Coimbatore, TUFIDCO/CCC- 5 Madurai, Salem, Thanjavur, Tiruchirapalli, Vellore, ES/1244/AM(M)/2018 Tirunelveli, Tiruppur, Thoothukudi and Erode) of Tamil Nadu Expression of Interest for Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Implementation in 10 Smart Cities TUFIDCO/CCC- 6 (Coimbatore, Madurai, Salem, Thanjavur, GIS/1245/AM(M)/2018 Tiruchirapalli, Vellore, Tirunelveli, Tiruppur, Thoothukudi and Erode) of Tamil Nadu Further EOI Presentation timeslot will be published on 2nd May 2018. -

Sankarapuram

SANKARAPURAM S. NO ROLL.NO NAME OF ADVOCATE ADDRESS DOOR NO.2, MANKOMBU VILLAGE, VANJIKUZHI 1 529/2013 AKKINIRAJ M. POST, SANKARAPURAM TALUK, VILLUPURAM DIST - 606 401 SOUTH STREET, POIKUNAM & POST 2 564/1996 ANBALAGAN P. SANKARAPURAM TALUK, VILLUPURAM DIST - 606401. MIDDLE STREET, POOTTAI & POST, 3 1426/2003 ANNAMALAI B. SANKARAPURAM, VILLUPURAM - 606401. NORTH STREET, MURARPALAYAM PO. 4 1811/2002 ARUMUGAM C. SANKARAPURAM TK. VILLUPURAM DT, PIN - 606208. BNR ILLAM, MOONGIL THURAIPATTU, 5 208/2015 ASHOK KUMAR N. SANKARAPURAM TALUK, VILLUPURAM DIST - 605 702 ARIYALUR PO. VILLAGE, SANKARAPURAM TK. 6 3305/2011 BALAMURUGAN R. VILLUPURAM DIST. 605801 NO.5, THEVANGAR STREET, VADAKKANANDAL 7 1452/2005 BALASUBRAMANIAN P. VILLAGE & POST, CHINNASALEM TALUK, VILLUPURAM, PIN - 606207. NEDUMANUR , SANKARPURAM, TIRUKOILUR, 8 706/1999 DEVENDRAN R. VILLUPURAM DT, PIN - 606208. PUDUPETTAI VILLAGE, R.V.NALLUR PO, 9 1203/1995 DEVENDRAN S. SANKARAPURAM TK, VILLUPURAM-606402. ARASAMPATTI PO, SANKARAPURAM (TK), 10 1546/1999 DHANASEKARAN G. VILLUPURAM DT. 606401 96/108, POOTAI ROAD, SANDARAPURAM, 11 358/1998 DURAI K. 606401, VILLUPURAM. OPP TO TALUK OFFICE, SANKANRAPURAM, 12 1063/1995 DURAI RAJ C. VILLUPURAM. 10/36, POOTTAI VILLAGE, SANKARAPURAM 13 1952/2004 ELAMARAN M. TALUK, VILLUPURAM DIST - 606401. 15/2, MURUGESAN STREET, CHETPET, 14 109/2002 ELANGOVAN A. CHENNAI - 31. NO.6, KATTUVANANJUR, SANKARAPURAM, 15 100/1991 ELANGOVAN G. VILLUPURAM-606401. N.V.K. ILLAM, T.R.K.MAIN ROAD, 16 1432/2000 JANARTHANAN J. SANKARAPURAM POST, VILLUPURAM. M. KANNAN, S/O MANICKAM, POIKKUNAM-(PO), 17 299/1994 KANNAN M. SANKARAPURAM-(TK), VILLUPURAM DT. 1/250, DEVAPALAYAM POST, SANGARAPURAM 18 75/2000 KANNAN P. TALUK, VILLUPURAM DIST. -

Tamil Nadu Panchayat Development Service – Assistant Director of Rural Development - Direct Recruitment for the Year 2006-07 –– Appointment - Orders Issued

ABSTRACT Public Services - Tamil Nadu Panchayat Development Service – Assistant Director of Rural Development - Direct Recruitment for the year 2006-07 –– Appointment - Orders Issued. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND PANCHAYAT RAJ (E1) DEPARTMENT G.O.Ms.No.105 Dated : 19.09.2009 Read : From the Secretary, Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission, Letter No.6667/OTD C1/2007, dated 18-09-2009. * * * * ORDER : In the letter read above, the Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission has forwarded the name of following 26 candidates selected through competitive examination under Group-I Services for appointment to the post of Assistant Director of Rural Development / Personal Assistant to Collector (Development) by direct recruitment for the year 2006-07, subject to the result of the Writ Petitions pending before the High Court of Madras and Madurai Bench of Madras High Court. 2. The Government approve the selection of candidates as communicated by the Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission for appointment as Assistant Director of Rural Development/ Personal Assistant to collector (Development) in the Tamil Nadu Panchayat Development Service for the year 2006-07. 3. The following 26 candidates are hereby regularly appointed as Assistant Director / Personal Assistant to Collector (Development) by Direct Recruitment in the Tamil Nadu Panchayat Development Service in the scale of pay of Rs.8,000-275-13500 (Pre-revised scale) and posted for training in the Districts noted against each as indicated below subject to the result of the Writ Petitions pending before the High Court of Madras and Madurai Bench of Madras High Court. ..2.. S.No Name of the Candidate District allotted 1 Tmt/Selvi.Kanchana, B. -

TO, 1 District Librarian, Salem District Central Library, Chera Rajan Salai

TO, District Librarian, TO, Librarian, 1 Salem District Central Library, 2 Thirumal City Branch Library, Chera rajan Salai, Kamaraj Vedding Building, Asthamppaty Main Road, Municipaliti Chess colection Salem- 636 007. Center Office Near Rajethira Shathiram, Salem- 636 009. TO, Librarian, TO, Librarian, 3 Swarnapuri Branch Library, 4 Ammapet Branch Library, Selva Vinayagar Temple Street, 84-B, Kanaga sapathi Street, SwarnapuriPost, Ammapet Post Office, Salem- 636 004. Salem- 636 003. TO, Librarian, TO, Librarian, 5 Ayothiya pattinam Branch Library, 6 Panamarthupatty Branch Library, Belur Main Road, Thiruvalluvar Road, Ayothiya pattinamPost, PanamarthupattyPost, Salem Taluk, Salem District- 636 203. SalemDistrict - 636 202. TO, Librarian, TO, Librarian, 7 Attaiyampatti Branch Library, 8 Vembatydhalam Branch Library, Attaiyampatti Gov Gir Hir Sce 2/245, Near Post offic Street, School Near Attaiyampatti Post,, VembatydhalamPost, Salem Taluk, SalemTaluk, Salem District- 636 501. Salem District- 637 504. TO, Librarian, TO, Librarian, 9 MallurBranch Library, 10 Sooramangalam Branch Library, 1/25 Athikuttai, 207, SooramangalamMain Road, MallurPost, Salem Taluk, SalemTaluk, Salem District- 636 005. Salem District- 636 203. TO, Librarian, TO, Librarian, 11 Minnampalli Branch Library, 12 Sivathapuram Branch Library, Mariyamman Temple Street, Maiyan Street, Minnampalli Post, Sivathapuram Post, Salem Taluk, Mariyamman Temple Street Near Salem District- 636 106. SalemTaluk, Salem District- 636 301. TO, Librarian, TO, Librarian, 13 Gugai Branch Library, 14 Palaniyamal Raja K.V Iyan Thiruvalluvar memoriyal, Branch Library, Ampalvana Swamy Temple Street, 26, Vallar Street, GugaiPost, KanangkuruchiPost, SalemTaluk, SalemTaluk, Salem District- 636 006. Salem District- 636 008. TO, Librarian, TO, Librarian, 15 Kondalampatty Branch Library, 16 Dhasanayakkanpatty Branch Muniappan Temple Street-3, Library, Ward No-10, 5/85, Thuruchy Main Road, KondalampattyPost, DhasanayakkanpattyPost, SalemTaluk, SalemTaluk, Salem District- 636 010.