HISTORY of 911 and What It Means for the Future of Emergency Communications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4-Line Intercom Speakerphone User's Guide

4-Line Intercom Speakerphone User’s Guide Quick Guide on Pgs. 7-14 Please read this manual before operating product for the first time. Model 25423/24 Important Information Equipment Approval Information Your telephone equipment is approved for connection to the Public Switched Telephone Network and is in compliance with parts 15 and 68, FCC Rules and Regulations and the Technical Requirements for Telephone Terminal Equipment published by ACTA. 1 Notification to the Local Telephone Company On the bottom of this equipment is a label indicating, among other information, the US number and Ringer Equivalence Number (REN) for the equipment. You must, upon request, provide this information to your telephone company. The REN is useful in determining the number of devices you may connect to your telephone line and still have all of these devices ring when your telephone number is called. In most (but not all) areas, the sum of the RENs of all devices connected to one line should not exceed 5. To be certain of the number of devices you may connect to your line as determined by the REN, you should contact your local telephone company. A plug and jack used to connect this equipment to the premises wiring and telephone network must comply with the applicable FCC Part 68 rules and requirements adopted by the ACTA. A compliant telephone cord and modular plug is provided with this product. It is designed to be connected to a compatible modular jack that is also compliant. See installation instructions for details. Notes • This equipment may not be used on coin service provided by the telephone company. -

Outline of Numbering in Japan

OutlineOutline ofof NumberingNumbering inin JapanJapan April 2010 SATO Kenji JICA Expert 1 ContentsContents 1. Outline of Current Situation and Basic Policy of Numbering 2. MNP (Mobile Number Portability) 3. Numbering Issues for NGN Era - FMC (Fixed Mobile Convergence) - ENUM 2 1.Outline of Current Situation and Basic Policy of Numbering 3 Telecommunications Number History in Japan Until 1985 NTT (Public company) managed all telecommunications numbers 1985 Liberalization of telecommunication sector Privatization of NTT New companies started telecommunications business. Big Bang of Telecommunications business. Necessity for Making telecommunications business rules. Telecommunications Numbers were defined on regulation for telecommunications facilities (1985) 4 The Function of Number - Service identification (Fixed? Mobile?) - Location identification (Near? Far?) - Tariff identification (If far, charge is high) - Quality identification (If fixed, better than mobile) - Social trust identification 5 Regulations for Telecommunication Numbers Telecommunication Business Law Article 50 (Standards for Telecommunications Numbers) (1) When any telecommunications carrier provides telecommunications services by using telecommunications numbers (numbers, signs or other codes that telecommunications carriers use in providing their telecommunications services, for identifying telecommunications facilities in order to connect places of transmission with places of reception, or identifying types or content of telecommunications services to provide; hereinafter the same shall apply), it shall ensure that its telecommunications numbers conform to the standards specified by an Ordinance of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. (2) The standards set forth in the preceding paragraph shall be specified so as to ensure the following matters: (i) The telecommunications numbers shall make it possible for telecommunications carriers and users to clearly and easily identify telecommunications facilities or types or content of the telecommunications services. -

Long Distance Calls

Long Distance Calls HOW TO PLACE LONG CALLS TO TELEPHONES WITH AUTOMATIC ANSWERING SETS, DISTANCE CALLS FAX MACHINES, MODEMS Long distance charges apply when dialing 1 +. DIRECTORY ASSISTANCE Charging begins when the called telephone is FOR LOCAL & LONG answered in person or by an automatic answering DISTANCE . DIAL 1 + 411 set, fax machine, modem, etc. When the Directory Assistance Operator answers, CALLS TO CELLULAR PHONES give her the city or town, then the name and Long distance charges will apply when dialing 1 +. address you wish to call. Jot down the number for future reference. CALLS TO MOBILE PHONES Long distance charges apply for use of the line to Effective May 25, 1984, the FCC approved charging get the tone signal for dialing additional numbers for Directory Assistance. whether the mobile phone is actually answered or not. MAKING YOUR CALL: STATION-TO-STATION PTCI LONG DISTANCE TRAVEL To use carrier picked to phone being used Dial 1 + CARD Area Code + phone number or to choose another Call the Business Office at 1-800-327-7525 to carrier 101 + Carriers Four Digit Access Code + 1 apply for a Travel Card today. The PTCI Travel Area Code + phone number. Card is your local calling card which is available free on request. It can be used across town on a Line Verification - Operator can verify if a line is payphone, in hospitals or on vacation. Use your busy. Operator service charges apply. PTCI Travel Card, you don’t need change, and calls Line Interruption - Operator can interrupt a conver- will be billed to your number. -

Zfone: a New Approach for Securing Voip Communication

Zfone: A New Approach for Securing VoIP Communication Samuel Sotillo [email protected] ICTN 4040 Spring 2006 Abstract This paper reviews some security challenges currently faced by VoIP systems as well as their potential solutions. Particularly, it focuses on Zfone, a vendor-neutral security solution developed by PGP’s creator, Phil Zimmermann. Zfone is based on the Z Real-time Transport Protocol (ZRTP), which is an extension of the Real-time Transport Protocol (RTP). ZRTP offers a very simple and robust approach to providing protection against the most common type of VoIP threats. Basically, the protocol offers a mechanism to guarantee high entropy in a Diffie- Hellman key exchange by using a session key that is computed through the hashing several secrets, including a short authentication string that is read aloud by callers. The common shared secret is calculated and used only for one session at a time. However, the protocol allows for a part of the shared secret to be cached for future sessions. The mechanism provides for protection for man-in-the-middle, call hijack, spoofing, and other common types of attacks. Also, this paper explores the fact that VoIP security is a very complicated issue and that the technology is far from being inherently insecure as many people usually claim. Introduction Voice over IP (VoIP) is transforming the telecommunication industry. It offers multiple opportunities such as lower call fees, convergence of voice and data networks, simplification of deployment, and greater integration with multiple applications that offer enhanced multimedia functionality [1]. However, notwithstanding all these technological and economic opportunities, VoIP also brings up new challenges. -

Central Telecom Long Distance, Inc

Central Telecom Long Distance, Inc. 102 South Tejon Street, 11th Floor Colorado Springs, CO 80903. Telecommunications Service Guide For Interstate and International Services May 2016 This Service Guide contains the descriptions, regulations, and rates applicable to furnishing of domestic Interstate and International Long Distance Telecommunications Services provided by Central Telecom Long Distance, Inc. (“Central Telecom Long Distance” or “Company”). This Service Guide and is available to Customers and the public in accordance with the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) Public Availability of Information Concerning Interexchange Services rules, 47 CFR Section 42.10. Additional information is available by contacting Central Telecom Long Distance, Inc.’s Customer Service Department toll free at 888.988.9818, or in writing directed to Customer Service, 102 South Tejon Street, 11th Floor, Colorado Springs, CO 80903. 1 INTRODUCTION This Service Guide contains the rates, terms, and conditions applicable to the provision of domestic Interstate and International Long Distance Services. This Service Guide is prepared in accordance with the Federal Communications Commission’s Public Availability of Information Concerning Interexchange Services rules, 47 C.F.R. Section 42.10 and Service Agreement and may be changed and/or discontinued by the Company. This Service Guide governs the relationship between Central Telecom Long Distance, Inc. and its Interstate and International Long Distance Service Customers, pursuant to applicable federal regulation, federal and state law, and any client-specific arrangements. In the event one or more of the provisions contained in this Service Guide shall, for any reason be held to be invalid, illegal, or unenforceable in any respect, such invalidity, illegality or unenforceability shall not affect any other provision hereof, and this Service Guide shall be construed as if such invalid, illegal or unenforceable provision had never been contained herein. -

From Telephone Fraud

Beware of International Modem Dialing If you use a dial-up modem to connect to the Internet and download a "viewer" or "dialer" computer program (usually offered for free to access a site), the program may disconnect your modem and then reconnect it to the Internet through an international long-distance Crime Prevention Tips From number without your knowledge or authorization. You NATIONAL CRIME PREVENTION COUNCIL will then receive a large international phone bill. 1000 Connecticut Avenue, NW From Thirteenth Floor Washington. DC 20036-5325 Tip: Install a dedicated phone line for your computer that 202-466-6272 is restricted to local calls. If that is notpossible, watch out www.ncpc.org Telephone for anyprogram that allows your modem to redial to the and Internet without your direction. Cancel the connection, and check the number your modem is dialing. Fraud The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is the federal agency responsible for regulating your telephone services. Go to its website, www.fcc.org, for information on how to review your telephone bill, how to spot cramming charges, and other telephone-related consumer issues. You can file a complaint by email ([email protected]), the Internet (www.fcc.gov/cgblcomplaints.html),or telephone (888-CALL-FCC [888-225-5322]). Bureau of Justlce Assistance Oli c* 0, ivrlicr PrDpram9. U 5 Oapnrlmanlol Jurlco The National Citizens' Crime Prevention Campaign, sponsored by the Crime Prevention Coalition of America, is substantially funded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Production made possible by a grant from ADT Security Services. -

Central Office Optional Features 2Nd Revised Sheet 1 SECTION 2 - Advanced Custom Calling Features Replacing 1St Revised Sheet 1

AT&T TEXAS GUIDEBOOK PART 7 - Central Office Optional Features 2nd Revised Sheet 1 SECTION 2 - Advanced Custom Calling Features Replacing 1st Revised Sheet 1 CUSTOM CALLING SERVICES A. General Regulations Refer to Part 7, Section 1 for regulations applicable to Custom Calling Services. B. Descriptions Auto Redial Enables the customer to redial automatically the last outgoing telephone number. If the telephone number is busy, Company equipment will keep trying to call the number for a maximum of thirty (30) minutes beginning with the customer’s activation of Auto Redial, in an attempt to establish the call. The customer will be signaled with a distinctive ring when the call can be completed. Call Blocker Enables the customer to block calls from preselected telephone numbers and/or the last incoming call (without knowing the number). To block specified telephone numbers, the customer builds a screening list. To block an unknown number after receiving a call, the customer enters a code to add the number to their screening list. If facilities are unavailable to provide incoming call screening via the customer’s list, standard call completion will occur. Customers whose telephone numbers are blocked are directed to a Company recorded announcement. Call Return Enables the customer to redial automatically the last incoming telephone number. If that telephone number is busy, Company equipment will keep trying to call the number for a maximum of thirty (30) minutes beginning with the customer’s activation of Call Return in an attempt to establish the call. The customer will be signaled with a distinctive ring when the call can be completed. -

Telecommunications Provider Locator

Telecommunications Provider Locator Industry Analysis & Technology Division Wireline Competition Bureau February 2003 This report is available for reference in the FCC’s Information Center at 445 12th Street, S.W., Courtyard Level. Copies may be purchased by calling Qualex International, Portals II, 445 12th Street SW, Room CY- B402, Washington, D.C. 20554, telephone 202-863-2893, facsimile 202-863-2898, or via e-mail [email protected]. This report can be downloaded and interactively searched on the FCC-State Link Internet site at www.fcc.gov/wcb/iatd/locator.html. Telecommunications Provider Locator This report lists the contact information and the types of services sold by 5,364 telecommunications providers. The last report was released November 27, 2001.1 All information in this report is drawn from providers’ April 1, 2002, filing of the Telecommunications Reporting Worksheet (FCC Form 499-A).2 This report can be used by customers to identify and locate telecommunications providers, by telecommunications providers to identify and locate others in the industry, and by equipment vendors to identify potential customers. Virtually all providers of telecommunications must file FCC Form 499-A each year.3 These forms are not filed with the FCC but rather with the Universal Service Administrative Company (USAC), which serves as the data collection agent. Information from filings received after November 22, 2002, and from filings that were incomplete has been excluded from the tables. Although many telecommunications providers offer an extensive menu of services, each filer is asked on Line 105 of FCC Form 499-A to select the single category that best describes its telecommunications business. -

At&T Michigan Guidebook Part 7

AT&T MICHIGAN GUIDEBOOK PART 7 - Central Office Optional Features 1st Revised Sheet 1 SECTION 3 - Complementary Network Services (CNS) COMPLEMENTARY NETWORK SERVICES (CNS) A. GENERAL 1. Complementary Network Services (CNS) have been developed and are to be implemented as an integral part of information type services. They are optional features that may access or work in conjunction with an enhanced service. 2. CNS are available to individual line business and residence exchange services, WATS line, and PBX trunks as specified herein excluding semi-public service, party line exchange services, or Centrex system stations. 3. CNS may be ordered by the user or an authorized agent of the end user. 4. CNS are provided only where facilities permit. B. DESCRIPTION OF FEATURES 1. Busy Line Transfer (previously known as Call Forwarding-Busy Line) a. Busy Line Transfer, formerly Call Forwarding-Busy Line, provides for the forwarding of an incoming call to another predetermined telephone when the dialed number is busy. If incoming calls are transferred to a number served by the same or a different central office switch, multiple calls will be transferred simultaneously provided that there are sufficient facilities to accept the calls. b. The grade of transmission on transferred calls may vary depending on the distance and routing necessary to complete such a call, therefore, the Company makes no representation as to the quality of transmission on any transferred call. 2. Alternate Answering (previously known as Call Forwarding-Don't Answer) a. Alternate Answering, formerly Call Forwarding-Don't Answer, provides for the forwarding of an incoming call to a predetermined telephone number, when the called number is not answered within a set numbers of rings. -

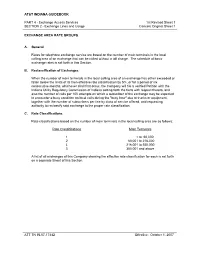

SECTION 2 - Exchange Lines and Usage Cancels Original Sheet 1

AT&T INDIANA GUIDEBOOK PART 4 - Exchange Access Services 1st Revised Sheet 1 SECTION 2 - Exchange Lines and Usage Cancels Original Sheet 1 EXCHANGE AREA RATE GROUPS A. General Rates for telephone exchange service are based on the number of main terminals in the local calling area of an exchange that can be called without a toll charge. The schedule of basic exchange rates is set forth in this Section. B. Reclassification of Exchanges When the number of main terminals in the local calling area of an exchange has either exceeded or fallen below the limits of its then effective rate classification by 5%, or for a period of six consecutive months, whichever shall first occur, the Company will file a verified Petition with the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission of Indiana setting forth the facts with respect thereto, and also the number of calls per 100 attempts on which a subscriber of the exchange may be expected to encounter a busy condition on local calls during the "busy hour" due to trunks or equipment, together with the number of subscribers per line by class of service offered, and requesting authority to reclassify said exchange to the proper rate classification. C. Rate Classifications Rate classifications based on the number of main terminals in the local calling area are as follows: Rate Classifications Main Terminals 1 1 to 60,000 2 60,001 to 216,000 L 216,001 to 350,000 3 350,001 and above A list of all exchanges of this Company showing the effective rate classification for each is set forth on a separate Sheet of this Section. -

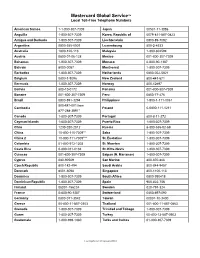

Mastercard Global Service Phone Numbers

Mastercard Global Service™ Local Toll-Free Telephone Numbers American Samoa 1-1-800-307-7309 Japan 00531-11-3886 Anguilla 1-800-307-7309 Korea, Republic of 0079-811-887-0823 Antigua and Barbuda 1-800-307-7309 Liechtenstein 0800-89-7092 Argentina 0800-555-0507 Luxembourg 800-2-4533 Australia 1800-120-113 Malaysia 1-800-804594 Austria 0800-07-06-138 Mexico 001-800-307-7309 Bahamas 1-800-307-7309 Monaco 0-800-90-1387 Bahrain 8000-0087 Montserrat 1-800-307-7309 Barbados 1-800-307-7309 Netherlands 0800-022-5821 Belgium 0800-1-5096 New Zealand 800-441-671 Bermuda 1-800-307-7309 Norway 800-12697 Bolivia 800-10-0172 Panama 001-800-307-7309 Bonaire 001-800-307-7309 Peru 0800-77-476 Brazil 0800-891-3294 Philippines 1-800-1-111-0061 800-881-001 then Cambodia Poland 0-0800-111-1211 877-288-3891* Canada 1-800-307-7309 Portugal 800-8-11-272 Cayman Islands 1-800-307-7309 Puerto Rico 1-800-307-7309 Chile 1230-020-2012 Russia 8-800-555-02-69 China 10-800-110-7309** Saba 1-800-307-7309 China 2 10-800-711-7309*** St. Eustatius 1-800-307-7309 Colombia 01-800-912-1303 St. Maarten 1-800-307-7309 Costa Rica 0-800-011-0184 St. Kitts-Nevis 1-800-307-7309 Curacao 001-800-307-7309 Saipan (N. Marianas) 1-800-307-7309 Cyprus 080-90569 San Marino 800-870-866 Czech Republic 800-142-494 Saudi Arabia 800-844-9457 Denmark 8001-6098 Singapore 800-1100-113 Dominica 1-800-307-7309 South Africa 0800-990418 Dominican Republic 1-800-307-7309 Spain 900-822-756 Finland 08001-156234 Sweden 020-791-324 France 0-800-90-1387 Switzerland 0800-897-092 Germany 0800-071-3542 Taiwan 00801-10-3400 -

GSM Voice Messaging System & Calling Features

GSM Voice Messaging System & Calling Features Voice Messaging offers you a complete answering system that allows you to retrieve messages from any phone, anywhere, 24 hours a day. When you have messages waiting, you will hear short bursts of dial tone when you pick up your telephone handset prior to making or receiving a call. Please refer to your GSM wireless phone manufacturer’s user guide to determine what type of voice mail icon or message waiting indicator will display on your particular phone when you have received a voice message. GSM Wireless Voice Mail Call Waiting Number of messages stored 20 This feature gives you the advantage of a second line Message Length 2 minutes without additional cost. Two short tones signal that a second party is trying to reach you while you are on Message Retention 14 days a call. Number of Greetings 9 To answer the incoming call: Greeting Length 1 minute 1. Press SEND. This puts the original call on hold and connects you to the second party. 2. Press SEND again to return to original party. You GSM Voice Mail Set Up: can switch back and forth between the two calls by To Set Up: pressing the SEND key. Press and hold 1 key. Call Forwarding GSM Wireless When Voice Message system answers press 9999# This feature allows all calls to be immediately Tutorial will start and explain how to set up security forwarded to a predetermined number you have code and greeting. programmed to accept all calls. To activate Call Forwarding: To Retrieve Voice Mail From GSM Phone: 1.