Externalities Microeconomics 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shopping Externalities and Self-Fulfilling Unemployment Fluctuations

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES SHOPPING EXTERNALITIES AND SELF-FULFILLING UNEMPLOYMENT FLUCTUATIONS Greg Kaplan Guido Menzio Working Paper 18777 http://www.nber.org/papers/w18777 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 February 2013 We thank the Kielts-Nielsen Data Center at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business for providing access to the Kielts-Nielsen Consumer Panel Dataset. We thank the editor, Harald Uhlig, and three anonymous referees for insightful and detailed suggestions that helped us revising the paper. We are also grateful to Mark Aguiar, Jim Albrecht, Michele Boldrin, Russ Cooper, Ben Eden, Chris Edmond, Roger Farmer, Veronica Guerrieri, Bob Hall, Erik Hurst, Martin Schneider, Venky Venkateswaran, Susan Vroman, Steve Williamson and Randy Wright for many useful comments. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2013 by Greg Kaplan and Guido Menzio. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Shopping Externalities and Self-Fulfilling Unemployment Fluctuations Greg Kaplan and Guido Menzio NBER Working Paper No. 18777 February 2013, Revised October 2013 JEL No. D11,D21,D43,E32 ABSTRACT We propose a novel theory of self-fulfilling unemployment fluctuations. According to this theory, a firm hiring an additional worker creates positive external effects on other firms, as a worker has more income to spend and less time to search for low prices when he is employed than when he is unemployed. -

Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine

with Open Texts Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine VERSION 2017 – REVISION B ADAPTABLE | ACCESSIBLE | AFFORDABLE Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-SA) advancing learning Champions of Access to Knowledge OPEN TEXT ONLINE ASSESSMENT All digital forms of access to our high- We have been developing superior on- quality open texts are entirely FREE! All line formative assessment for more than content is reviewed for excellence and is 15 years. Our questions are continuously wholly adaptable; custom editions are pro- adapted with the content and reviewed for duced by Lyryx for those adopting Lyryx as- quality and sound pedagogy. To enhance sessment. Access to the original source files learning, students receive immediate per- is also open to anyone! sonalized feedback. Student grade reports and performance statistics are also provided. SUPPORT INSTRUCTOR SUPPLEMENTS Access to our in-house support team is avail- Additional instructor resources are also able 7 days/week to provide prompt resolu- freely accessible. Product dependent, these tion to both student and instructor inquiries. supplements include: full sets of adaptable In addition, we work one-on-one with in- slides and lecture notes, solutions manuals, structors to provide a comprehensive sys- and multiple choice question banks with an tem, customized for their course. This can exam building tool. include adapting the text, managing multi- ple sections, and more! Contact Lyryx Today! [email protected] advancing learning Principles of Microeconomics an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine Version 2017 — Revision B BE A CHAMPION OF OER! Contribute suggestions for improvements, new content, or errata: A new topic A new example An interesting new question Any other suggestions to improve the material Contact Lyryx at [email protected] with your ideas. -

Microeconomics III Oligopoly — Preface to Game Theory

Microeconomics III Oligopoly — prefacetogametheory (Mar 11, 2012) School of Economics The Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya Oligopoly is a market in which only a few firms compete with one another, • and entry of new firmsisimpeded. The situation is known as the Cournot model after Antoine Augustin • Cournot, a French economist, philosopher and mathematician (1801-1877). In the basic example, a single good is produced by two firms (the industry • is a “duopoly”). Cournot’s oligopoly model (1838) — A single good is produced by two firms (the industry is a “duopoly”). — The cost for firm =1 2 for producing units of the good is given by (“unit cost” is constant equal to 0). — If the firms’ total output is = 1 + 2 then the market price is = − if and zero otherwise (linear inverse demand function). We ≥ also assume that . The inverse demand function P A P=A-Q A Q To find the Nash equilibria of the Cournot’s game, we can use the proce- dures based on the firms’ best response functions. But first we need the firms payoffs(profits): 1 = 1 11 − =( )1 11 − − =( 1 2)1 11 − − − =( 1 2 1)1 − − − and similarly, 2 =( 1 2 2)2 − − − Firm 1’s profit as a function of its output (given firm 2’s output) Profit 1 q'2 q2 q2 A c q A c q' Output 1 1 2 1 2 2 2 To find firm 1’s best response to any given output 2 of firm 2, we need to study firm 1’s profit as a function of its output 1 for given values of 2. -

Learning Externalities and Economic Growth

Learning Externalities and Economic Growth Alejandro M. Rodriguez∗ August 2004 ∗I would like to thank Profesor Robert E. Lucas for motivating me to write this paper and for his helpful comments. Profesor Alvarez also provided some useful insights. Please send comments to [email protected]. All errors are mine. ABSTRACT It is a well known fact that not all countries develop at the same time. The industrial revolution began over 200 years ago in England and has been spreading over the world ever since. In their paper Barriers to Riches, Parente and Prescott notice that countries that enter the industrial stage later on grow faster than what the early starters did. I present a simple model with learning externalities that generates this kind of behavior. I follow Lucas (1998) and solve the optimization problem of the representative agent under the assumption that the external effect is given by the world leader’s human capital. 70 60 50 40 30 20 Number of years to double income 10 0 1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 Year income reached 2,000 (1990 U.S. $) Fig. 1. Growth patterns from Parente and Prescott 1. Introduction In Barriers to Riches, Parente and Prescott observe that ”Countries reaching a given level of income at a later date typically double that level in a shorter time ” To support this conclusion they present Figure 1 Figure 1 shows the year in which a country reached the per capita income level of 2,000 of 1990 U.S. dollars and the number of years it took that country to double its per capita income to 4,000 of 1990 U.S. -

ECON - Economics ECON - Economics

ECON - Economics ECON - Economics Global Citizenship Program ECON 3020 Intermediate Microeconomics (3) Knowledge Areas (....) This course covers advanced theory and applications in microeconomics. Topics include utility theory, consumer and ARTS Arts Appreciation firm choice, optimization, goods and services markets, resource GLBL Global Understanding markets, strategic behavior, and market equilibrium. Prerequisite: ECON 2000 and ECON 3000. PNW Physical & Natural World ECON 3030 Intermediate Macroeconomics (3) QL Quantitative Literacy This course covers advanced theory and applications in ROC Roots of Cultures macroeconomics. Topics include growth, determination of income, employment and output, aggregate demand and supply, the SSHB Social Systems & Human business cycle, monetary and fiscal policies, and international Behavior macroeconomic modeling. Prerequisite: ECON 2000 and ECON 3000. Global Citizenship Program ECON 3100 Issues in Economics (3) Skill Areas (....) Analyzes current economic issues in terms of historical CRI Critical Thinking background, present status, and possible solutions. May be repeated for credit if content differs. Prerequisite: ECON 2000. ETH Ethical Reasoning INTC Intercultural Competence ECON 3150 Digital Economy (3) Course Descriptions The digital economy has generated the creation of a large range OCOM Oral Communication of significant dedicated businesses. But, it has also forced WCOM Written Communication traditional businesses to revise their own approach and their own value chains. The pervasiveness can be observable in ** Course fulfills two skill areas commerce, marketing, distribution and sales, but also in supply logistics, energy management, finance and human resources. This class introduces the main actors, the ecosystem in which they operate, the new rules of this game, the impacts on existing ECON 2000 Survey of Economics (3) structures and the required expertise in those areas. -

Working Paper No. 517 What Are the Relative Macroeconomic Merits And

Working Paper No. 517 What Are the Relative Macroeconomic Merits and Environmental Impacts of Direct Job Creation and Basic Income Guarantees? by Pavlina R. Tcherneva The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College October 2007 The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection presents research in progress by Levy Institute scholars and conference participants. The purpose of the series is to disseminate ideas to and elicit comments from academics and professionals. The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, founded in 1986, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, independently funded research organization devoted to public service. Through scholarship and economic research it generates viable, effective public policy responses to important economic problems that profoundly affect the quality of life in the United States and abroad. The Levy Economics Institute P.O. Box 5000 Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504-5000 http://www.levy.org Copyright © The Levy Economics Institute 2007 All rights reserved. ABSTRACT There is a body of literature that favors universal and unconditional public assurance policies over those that are targeted and means-tested. Two such proposals—the basic income proposal and job guarantees—are discussed here. The paper evaluates the impact of each program on macroeconomic stability, arguing that direct job creation has inherent stabilization features that are lacking in the basic income proposal. A discussion of modern finance and labor market dynamics renders the latter proposal inherently inflationary, and potentially stagflationary. After studying the macroeconomic viability of each program, the paper elaborates on their environmental merits. It is argued that the “green” consequences of the basic income proposal are likely to emerge, not from its modus operandi, but from the tax schemes that have been advanced for its financing. -

FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE August 23 –– December 9, 2021

9/15/21 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE August 23 –– December 9, 2021 Course # Class # Units Course Title Day Time Location Instruction Mode Instructor Limit 1078-001 20457 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 MWF 8:00-8:50 ECON 117 IN PERSON Bentz 47 1078-002 20200 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 MWF 6:30-7:20 ECON 119 IN PERSON Hurt 47 1078-004 13409 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Marein 71 1088-001 18745 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 2 MWF 6:30-7:20 HLMS 141 IN PERSON Zhou, S 47 1088-002 20748 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 2 MWF 8:00-8:50 HLMS 211 IN PERSON Flynn 47 2010-100 19679 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Keller 500 2010-200 14353 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Carballo 500 2010-300 14354 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Bottan 500 2010-600 14355 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Klein 200 2010-700 19138 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Gruber 200 2020-100 14356 4 Principles of Macroeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Valkovci 400 3070-010 13420 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory MWF 9:10-10:00 ECON 119 IN PERSON Barham 47 3070-020 21070 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory TTH 2:20-3:35 ECON 117 IN PERSON Chen 47 3070-030 20758 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory TTH 11:10-12:25 ECON 119 IN PERSON Choi 47 3070-040 21443 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory MWF 1:50-2:40 ECON 119 IN PERSON Bottan 47 3080-001 22180 3 Intermediate Macroeconomic Theory MWF 11:30-12:20 -

Product Differentiation

Product differentiation Industrial Organization Bernard Caillaud Master APE - Paris School of Economics September 22, 2016 Bernard Caillaud Product differentiation Motivation The Bertrand paradox relies on the fact buyers choose the cheap- est firm, even for very small price differences. In practice, some buyers may continue to buy from the most expensive firms because they have an intrinsic preference for the product sold by that firm: Notion of differentiation. Indeed, assuming an homogeneous product is not realistic: rarely exist two identical goods in this sense For objective reasons: products differ in their physical char- acteristics, in their design, ... For subjective reasons: even when physical differences are hard to see for consumers, branding may well make two prod- ucts appear differently in the consumers' eyes Bernard Caillaud Product differentiation Motivation Differentiation among products is above all a property of con- sumers' preferences: Taste for diversity Heterogeneity of consumers' taste But it has major consequences in terms of imperfectly competi- tive behavior: so, the analysis of differentiation allows for a richer discussion and comparison of price competition models vs quan- tity competition models. Also related to the practical question (for competition authori- ties) of market definition: set of goods highly substitutable among themselves and poorly substitutable with goods outside this set Bernard Caillaud Product differentiation Motivation Firms have in general an incentive to affect the degree of differ- entiation of their products compared to rivals'. Hence, differen- tiation is related to other aspects of firms’ strategies. Choice of products: firms choose how to differentiate from rivals, this impacts the type of products that they choose to offer and the diversity of products that consumers face. -

Economics Chair: Marian Manic Sai Mamunuru Halefom Belay Rosie Mueller Jan P

Economics Chair: Marian Manic Sai Mamunuru Halefom Belay Rosie Mueller Jan P. Crouter Jason Ralston Denise Hazlett Economics is the study of how people and societies choose to use scarce resources in the production of goods and services, and of the distribution of these goods and services among individuals and groups in society. The economics major requires coursework in economics and mathematics. A student who enters Whitman with no prior college-level work in either of these areas would need to complete math 125 and complete at least 35 credits in economics. Learning Goals: Upon graduation, a student will be able to demonstrate: Major-Specific Areas of Knowledge o Students should have an understanding of how economics can be used to explain and interpret a) the behavior of agents (for example, firms and households) and the markets or settings in which they interact, and b) the structure and performance of national and global economies. Students should also be able to evaluate the structure, internal consistency and logic of economic models and the role of assumptions in economic arguments. Communication o Students should be able to communicate effectively in written, spoken, graphical, and quantitative form about specific economic issues. Critical Reasoning o Students should be able to apply economic analysis to evaluate everyday problems and policy proposals and to assess the assumptions, reasoning and evidence contained in an economic argument. Quantitative Analysis o Students should grasp the mathematical logic of standard macroeconomic and microeconomic models. o Students should know how to use empirical evidence to evaluate an economic argument (including the collection of relevant data for empirical analysis, statistical analysis, and interpretation of the results of the analysis) and how to understand empirical analyses of others. -

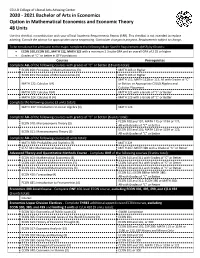

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

I. Externalities

Economics 1410 Fall 2017 Harvard University SECTION 8 I. Externalities 1. Consider a factory that emits pollution. The inverse demand for the good is Pd = 24 − Q and the inverse supply curve is Ps = 4 + Q. The marginal cost of the pollution is given by MC = 0:5Q. (a) What are the equilibrium price and quantity when there is no government intervention? (b) How much should the factory produce at the social optimum? (c) How large is the deadweight loss from the externality? (d) How large of a per-unit tax should the government impose to achieve the social optimum? 2. In Karro, Kansas, population 1,001, the only source of entertainment available is driving around in your car. The 1,001 Karraokers are all identical. They all like to drive, but hate congestion and pollution, resulting in the following utility function: Ui(f; d; t) = f + 16d − d2 − 6t=1000, where f is consumption of all goods but driving, d is the number of hours of driving Karraoker i does per day, and t is the total number of hours of driving all other Karraokers do per day. Assume that driving is free, that the unit price of food is $1, and that daily income is $40. (a) If an individual believes that the amount of driving he does wont affect the amount that others drive, how many hours per day will he choose to drive? (b) If everybody chooses this number of hours, then what is the total amount t of driving by other persons? (c) What will the utility of each resident be? (d) If everybody drives 6 hours a day, what will the utility level of each Karraoker be? (e) Suppose that the residents decided to pass a law restricting the total number of hours that anyone is allowed to drive. -

1. Introduction : (A) What Is Public Economics? First, a Very Brief and Broad Outline of the Structure of Government Finance, Pa

1. Introduction : (a) What is Public Economics? First, a very brief and broad outline of the structure of government finance, particularly government revenue sources, in Canada. In other words, \what level of government levies what tax, and how important are the different taxes?". Before that, an important message. This course is a fourth{year level course. The pre- requisites are intermediate microeconomics, and intermediate macroeconomics : AP/ECON 2300, 2350, 2400 and 2450, or their equivalents. Those prerequisites are meant to be taken seriously. In particular, you will find out very soon that this course is a course in the application of microe- conomic theory. It is microeconomic theory applied to taxation. Some of the concepts used in Econ 2300 and 2350 are going to get used here again | every day. Indifference curves, income and substitution effects, general equilibrium prices : these will keep popping up. So this is a double warning : (i) you have to have the formal prerequisites in order to get in to the course, and (ii) the course content is going to keep reminding you of material from Econ 2300 and 2350. Why is this course full of microeconomic theory? Because economists think that the concepts of microeconomic theory are useful in analyzing the behaviour of consumers and workers and firms and voters. And because much of the subject matter of the course is the effects of taxation on the behaviour of these economic agents, and the analysis of how the behaviour of these economic agents should affect the government's choices of taxes. Why microeconomics? After all, there is something pretty public about most of the material in macroeconomics.