Life History Account for Common Sagebrush Lizard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reptile and Amphibian List RUSS 2009 UPDATE

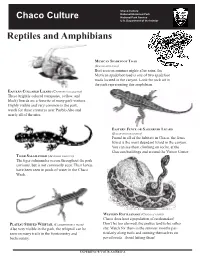

National CHistoricalhaco Culture Park National ParkNational Service Historical Park Chaco Culture U.S. DepartmentNational of Park the Interior Service U.S. Department of the Interior Reptiles and Amphibians MEXICAN SPADEFOOT TOAD (SPEA MULTIPLICATA) Best seen on summer nights after rains, the Mexican spadefoot toad is one of two spadefoot toads located in the canyon. Look for rock art in the park representing this amphibian. EASTERN COLLARED LIZARD (CROTAPHYTUS COLLARIS) These brightly colored (turquoise, yellow, and black) lizards are a favorite of many park visitors. Highly visible and very common in the park, watch for these creatures near Pueblo Alto and nearly all of the sites. EASTERN FENCE OR SAGEBRUSH LIZARD (SCELOPORUS GRACIOSUS) Found in all of the habitats in Chaco, the fence lizard is the most abundant lizard in the canyon. You can see them climbing on rocks, at the Chacoan buildings and around the Visitor Center. TIGER SALAMANDER (ABYSTOMA TIGRINUM) The tiger salamander occurs throughout the park environs, but is not commonly seen. Their larvae have been seen in pools of water in the Chaco Wash. WESTERN RATTLESNAKE (CROTALUS VIRIDIS) Chaco does host a population of rattlesnakes! PLATEAU STRIPED WHIPTAIL (CNEMIDOPHORUS VALOR) Don’t be too alarmed, the snakes tend to be rather Also very visible in the park, the whiptail can be shy. Watch for them in the summer months par- seen on many trails in the frontcountry and ticularly along trails and sunning themselves on backcountry. paved roads. Avoid hitting them! EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA Amphibian and Reptile List Chaco Culture National Historical Park is home to a wide variety of amphibians and reptiles. -

Sagebrush Steppe Poster

12 13 7 1 17 3 16 15 23 20 30 26 25 14 21 2 27 22 9 11 4 5 31 29 18 33 28 32 8 19 10 24 6 MAMMALS REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS BIRDS INSECTS PLANTS 27. Plains Pricklypear 1. Pronghorn 8. Great Basin Spadefoot Toad 12. Prairie Falcon (Falco mexicanus) 18. Harvester Ant 21. Wyoming Big Sagebrush (Opuntia polycantha) (Antilocapra americana) (Spea intermontana) 13. Northern Harrier (Pogonomyrmex sp.) (Artemesia tridentata var. 28. Scarlet Globemallow 2. Badger (Taxidea taxus) 9. Sagebrush Lizard (Circus cyaneus) 19. Darkling Beetle wyomingensis) (Sphaeralcea coccinea) 3. White-tailed Prairie Dog (Sceloporus graciosus) 14. Brewer’s Sparrow (Eleodes hispilabris) 22. Mountain Big Sagebrush 29. Tapertip Hawksbeard (Cynomys leucurus) 10. Short Horned Lizard (Spizella breweri) 20. Hera Moth (Hemileuca hera) (Artemesia tridentata var. (Crepis acuminata) 4. White-tailed Jackrabbit (Phrynosoma hernadesi) 15. Sage Thrasher varvaseyana) 30. Yarrow (Lepus townsendii) 11. Prairie Rattlesnake (Oreoscoptes montanus) 23. Rabbitbrush (Achillea millefolium var. lanulosa) 5. Pygmy Rabbit (Crotalus viridis) 16. Sage Sparrow (Amphispiza belli) OTHER (Chrysithamnus nauseosus) 31. Purple Milkvetch (Brachylagus idahoensis) 17. Greater Sage-grouse 32. Bacteria 24. Western Wheatgrass (Astragalus spp.) 6. Sagebrush vole (Centrocercus urophasianus) 33. Fungus (Pascopyrum smithii) (Lemmiscus curtatus) 25. Needle and Thread Grass 7. Coyote (Canis latrans) (Hesperostipa comata) 26. Bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata) ROCKIES.AUDUBON.ORG All living things need a HABITAT or a place where they can find shelter, food, water, and have space to move, live, and reproduce. Your shelter might be a house, a mobile home, or an apartment. You go to the grocery store to get food and your water comes out of a faucet. -

Sceloporus Graciosus Baird and Girard Ships

386.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SAURIA: IGUANIDAE SCELOPORUS GRACIOSUS Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. regulation and body temperatures by Cole (1943), Bogert (1949), Brattstrom (1965), Licht (1965), Cunningham (1966) and Mueller CENSKY,ELLENJ. 1986. Sceloporus graciosus. (1969, 1970a). Derickson (1974) reported on lipid deposition and utilization, and Norris (1965) reviewed color and thermal relation. Sceloporus graciosus Baird and Girard ships. Temperature and energy characteristics were reviewed by Dawson and Poulson (1962) and Mueller (1969, 1970b). Kerfoot Sagebrush lizard (1968) described geographic variation clines. Anatomical studies have been done on the preanal gland (Gabe and Saint Girons, 1965; Sceloporus graciosus Baird and Girard, 1852a:69. Type-locality, Burkholder and Tanner, 1974b); integument (Hunsacker and John• "Valley of the Great Salt Lake" [Utah]. Syntypes, Nat. Mus. son, 1959; Burstein et aI., 1974; Cole and Van Devender, 1976); Natur. Hist. (USNM) 2877 (4 specimens), collected by H. dentition (Hotton, 1955; Yatkola, 1976); thyroid (Lynn et aI., 1966) Stansbury, date unknown. Not examined by author. and skeleton (Etheridge, 1964; Presch, 1970; Larsen and Tanner, Sceloporus consobrinus: Yarrow, 1875:574 (part). See REMARKS. 1974). Age.dependent allozyme variation was studied by Tinkle and Sceloporus gratiosus: Yarrow, 1875:576. Emendation. Selander (1973), and hemoglobin variation by Guttman (1970). Sceloporus consobrinus gratiosus: Yarrow, 1882:62 (part). Behavior was reported by Cunningham (1955b), Carpenter (1978) Sceloporus undulatus consobrinus: Cope, 1900:377 (part). See REMARKS. and Ferguson (1971, 1973), and parasites by Woodbury (1934), Wood (1935), Waitz (1961), Allred and Beck (1962), Telford (1970) • CONTENT.Four subspecies are recognized: arenicolous, grac• and Pearce and Tanner (1973). Sceloporus graciosus was reported ilis, graciosus and vandenburgianus. -

Ventral Coloration and Body Condition Do Not Affect Territorial Behavior in Two Sceloporus Lizards

Ventral coloration and body condition do not affect territorial behavior in two Sceloporus lizards 1Marina Kelada, 1Courtney Moulton, 2Casey Nguyen, 3Griselda Robles Olague 1University of California, Riverside; 2University of California, Irvine; 3University of California, Santa Barbara Sceloporus lizards are known to be defensive of their territories, which provide shelter, food, water, and mates. They often exhibit territorial behavior through visual displays of aggression, specifically with pushups. Along with aggression, this display can also expose the blue coloration on their ventral side, serving as an intraspecific communication between lizards that reveals information about their dominance, sex, and species membership. In this study, we compared how blue coloration and body condition affected territorial behavior in two Sceloporus lizards: the well-studied western fence (Sceloporus occidentalis) and the understudied sagebrush (Sceloporus graciosus), two closely related lizards with overlapping ranges in the San Jacinto Mountains. We also addressed whether these species would exhibit character displacement in their ventral coloration as a result of their sympatry. ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop were used for photo analyses to quantify the proportion and intensity of blue on each lizard’s ventral side. Territoriality was measured through number of pushups displayed and distance traveled. We found that both ventral coloration and body condition had no effect on the territoriality of either species, suggesting that territorial behavior -

Saving the Sagebrush Sea This Iconic

Saving theSagebrush Sea: An Imperiled Western Legacy ind blows across the vast open space, sweeping species, such as elk, pronghorn, mule deer and golden eagles, the sweet scent of sage through the air. A herd of depend on sagebrush habitat for their survival. One small, pronghornW swiftly move across the landscape, stopping now brown, chicken-like bird, called the greater sage-grouse, is at and then to feed on the grasses and shrubs. Large eagles and the heart of efforts to save the sagebrush steppe. falcons swirl in the wind high above the land, while small song The Bureau of Land Management, state and local birds perch on sagebrush. This scene plays out across millions agencies, private landowners, sportsmen and women, and of acres in the American West on a stage called the sagebrush conservationists are working together to conserve the steppe. This iconic Western landscape is an important habitat sagebrush steppe for wildlife and sustainable economic for both wildlife and people. growth in the West. Sportsmen and women want to see the The sagebrush steppe dominates much of western North bird's populations rebound and the sagebrush steppe thrive-- America’s countryside, thriving in the arid deserts through and continue their commitment to conservation efforts aimed dry, hot summers and cold winters. Historically, sagebrush at avoiding the necessity of a listing under the Endangered stretched across roughly 153 million acres in many diverse Species Act. This landscape is vital for hunters, anglers, places such as valleys, mountains, grass-lands and dense recreationists, ranchers, responsible energy developers and shrub land. -

Why Care About America's Sagebrush?

U.S. U.S.Fish Fish & Wildlife & Wildlife Service Service Why Care About America’s Sagebrush? Male pronghorn at a Greater sage-grouse lek / USFWS Introduction Conservation Value The sage-steppe ecosystem of the Functionally, sage-steppe serves as a Despite the significant values it western United States is, to the casual nursery area for a multitude of wildlife provides to wildlife and humans, the eye, an arid and monotonous expanse species. sage-steppe ecosystem is one of the of sagebrush (Artemisia tridentate most imperiled ecosystems in America. Nutt.) that early European settlers Human Values Recently, the prospect of a Greater could not wait to traverse on westward Beginning with the Native American sage-grouse Endangered Species Act journeys. Yet, this “flyover country,” peoples who used the sage-steppe for listing has brought additional attention which may appear devoid of life and hunting and other subsistence to the condition of the sage-steppe thus immune to human impact, is in activities, this vast intermountain system. This iconic bird’s habitat has fact the most widespread ecosystem landscape has long held economic value been fragmented by development of type in the United States, one that for humans. As Europeans colonized sagebrush environments and there has teems with wildlife and also contains the West and established large-scale been a considerable loss of suitable other important natural resources that agricultural economies, sagebrush sagebrush habitat to support the bird’s fuel our nation’s economy. Across the communities became – and remain life history, including its needs for food, sage-steppe, a diverse array of – central to livestock grazing cover and nesting space. -

Shedd, Jackson, 2009: Bilateral Asymmetry in Two Secondary

BILATERAL ASYMMETRY IN TWO SECONDARY SEXUAL CHARACTERS IN THE WESTERN FENCE LIZARD (SCELOPORUS OCCIDENTALIS): IMPLICATIONS FOR A CORRELATION WITH LATERALIZED AGGRESSION ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Biological Sciences ____________ by Jackson D. Shedd Spring 2009 BILATERAL ASYMMETRY IN TWO SECONDARY SEXUAL CHARACTERS IN THE WESTERN FENCE LIZARD (SCELOPORUS OCCIDENTALIS): IMPLICATIONS FOR A CORRELATION WITH LATERALIZED AGGRESSION A Thesis by Jackson D. Shedd Spring 2009 APPROVED BY THE DEAN OF THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE, INTERNATIONAL, AND INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES: _________________________________ Susan E. Place, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: _________________________________ _________________________________ Abdel-Moaty M. Fayek Tag N. Engstrom, Ph.D., Chair Graduate Coordinator _________________________________ Donald G. Miller, Ph.D. _________________________________ Raymond J. Bogiatto, M.S. DEDICATION To Mela iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research was conducted under Scientific Collecting Permit #803021-02 granted by the California Department of Fish and Game. For volunteering their time and ideas in the field, I thank Heather Bowen, Dr. Tag Engstrom, Dawn Garcia, Melisa Garcia, Meghan Gilbart, Mark Lynch, Colleen Martin, Julie Nelson, Michelle Ocken, Eric Olson, and John Rowden. Thank you to Brian Taylor for providing the magnified photographs of femoral pores. Thank you to Brad Stovall for extended cell phone use in the Mojave Desert while completing the last hiccups with this project. Thank you to Nuria Polo-Cavia and Dr. Nancy Carter for assistance and noticeable willingness to help with statistical analysis. Thank you to Dr. Diana Hews for providing direction for abdominal patch measurements and quantification. -

Impacts of Off-Highway Motorized Vehicles on Sensitive Reptile Species in Owyhee County, Idaho

Impacts of Off-Highway Motorized Vehicles on Sensitive Reptile Species in Owyhee County, Idaho by James C. Munger and Aaron A. Ames Department of Biology Boise State University, Boise, ID 83725 Final Report of Research Funded by a Cost-share Agreement between Boise State University and the Bureau of Land Management June 1998 INTRODUCTION As the population of southwestern Idaho grows, there is a corresponding increase in the number of recreational users of off-highway motorized vehicles (OHMVs). An extensive trail system has evolved in the Owyhee Front, and several off-highway motorized vehicle races are proposed for any given year. Management decisions by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) regarding the use of public lands for OHMV activity should take account of the impact of OHMV activity on wildlife habitat and populations. However, our knowledge of the impact of this increased activity on many species of native wildlife is minimal. Of particular interest is the herpetofauna of the area: the Owyhee Front includes the greatest diversity of reptile species of any place in Idaho, and includes nine lizard species and ten snake species (Table 1). Three of these species are considered to be "sensitive" by BLM and Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG): Sonora semiannulata (western ground snake), Rhinocheilus lecontei (long-nosed snake), and Crotaphytus bicinctores (Mojave black-collared lizard). One species, Hypsiglena torquata (night snake), was recently removed from the sensitive list, but will be regarded as "sensitive" for the purposes of this report. Off-highway motorized vehicles could impact reptiles in several ways. First, they may run over and kill individuals. -

Dunes Sagebrush Lizard Petition

1 May 8, 2018 Mr. Ryan Zinke Secretary of the Interior Office of the Secretary Department of the Interior 18th and “C” Street, N.W. Washington DC 20202 Subject: Petition to List the Dunes Sagebrush Lizard as a Threatened or Endangered Species and Designate Critical Habitat Dear Secretary Zinke: The Center for Biological Diversity and Defenders of Wildlife hereby formally petition to list the dunes sagebrush lizard (Sceloperus arenicolus) as a threatened or endangered species under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.). This petition is filed under 5 U.S.C. § 553(e) and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14, which grant interested parties the right to petition for the issuance of a rule from the Assistant Secretary of the Interior. The Petitioners also request that critical habitat be designated for S. arenicolus concurrent with the listing, as required by 16 U.S.C. § 1533(b)(6)(C) and 50 C.F.R. § 424.12, and pursuant to the Administrative Procedures Act (5 U.S.C. § 553). The Petitioners understand that this petition sets in motion a specific process, placing defined response requirements on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and specific time constraints on those responses. See 16 U.S.C. § 1533(b). Petitioners The Center for Biological Diversity is a national, non-profit conservation organization with more than 1.6 million members and online activists dedicated to protecting diverse native species and habitats through science, policy, education, and the law. It has offices in 11 states and Mexico. -

Translocation of Dunes Sagebrush Lizards (Sceloporus Arenicolus) to Unoccupied Habitat in Crane County, Texas

TRANSLOCATION OF DUNES SAGEBRUSH LIZARDS (SCELOPORUS ARENICOLUS) TO UNOCCUPIED HABITAT IN CRANE COUNTY, TEXAS FINAL REPORT Mickey R. Parker 1, Wade A. Ryberg 2, Toby J. Hibbitts 1,2, Lee A. Fitzgerald 1 1 Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collections, Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 2 Natural Resources Institute, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 31 December 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Research that demonstrates the feasibility of establishing translocated populations of dunes sagebrush lizards is important for conservation and management of the species. This final report includes all results from a four-year research project designed to evaluate the feasibility of establishing translocated populations of dunes sagebrush lizards from relatively large source populations to unoccupied habitat in an area where the species was historically present. This research was the first and only conservation translocation for the dunes sagebrush lizard. During Project Years 1 and 2, we translocated 76 dunes sagebrush lizards (70 adults and 6 hatchlings; 21 male and 55 female) to an unoccupied site in Crane County, TX. The site consists of suitable habitat with a historical locality where the species no longer occurs. Translocated lizards acclimated to their new surroundings in soft-release enclosures then were released. Intensive post-translocation population monitoring took place over a dense grid of traps that covered 14.7 ha. We also conducted 415 person-hours of visual encounter surveys to increase the chances of finding a dunes sagebrush lizard at the site. Behavioral observations showed the lizards exhibited normal behaviors. During all project years we conducted 51 trapping sessions amounting to the impressive sum of 112,451 trap-days. -

Sagebrush Lizard April 2017

Volume 30/Issue 8 Sagebrush Lizard April 2017 SAGEBRUSH LIZARD INSIDE: Reptiles Cleaver Defenses Go Herping! SAGEBRUSH LIZARD © Charles Peterson, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Flickr hat is the most common lizard on showing off the blue patches. This is a warning Idaho’s sagebrush plains? It is the to back off and leave. sagebrush lizard! W The blue patches may also help to get the As you have probably figured out, the sagebrush attention of a passing female. Males put on a lizard likes habitats with sagebrush and other show by bobbing their heads and shaking their shrubs. It may also be found in wooded areas bodies. Sagebrush lizards mate in the spring. In with juniper, pines or Douglas-fir trees. They like June, females lay four to seven eggs in loose soil to bask in the sun on rocks or logs. under a shrub. If conditions are good, females may lay two clutches of eggs. Tiny, one-inch Some people call sagebrush lizards “blue- hatchlings emerge in August. bellies.” Mature males have two bright blue patches on their bellies. Females and immature Sagebrush lizards eat mostly insects. Ants, males have white or cream colored bellies. The beetles and flies are favorites. They may also eat tops of sagebrush lizards are covered in small, spiders and ticks. Their biggest predators are gray or tan spiny scales. They often have light snakes, especially whipsnakes and night snakes. colored stripes running down the back and may Hawks and other birds may also eat sagebrush have tinges of orange or yellow along the neck lizards. -

Impact of Dunes Sagebrush Lizard on Oil and Gas Activities in New Mexico: Bureau of Land Management Lease Offerings and Nominations in 2010-2011

Impact of Dunes Sagebrush Lizard on Oil and Gas Activities in New Mexico: Bureau of Land Management Lease Offerings and Nominations in 2010-2011 Jay C. Lininger* and Curt Bradley+ * Ecologist, Center for Biological Diversity, P.O. Box 25686, Albuquerque, NM 87125, [email protected] + GIS Specialist, Center for Biological Diversity, P.O. Box 710, Tucson, AZ 85702 Introduction Opponents of protecting the dunes sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus arenicolus) under the Endangered Species Act claim that federal listing of the reptile will severely restrict or eliminate oil and gas leasing on public lands.1 Rep. Steve Pearce of New Mexico’s second congressional district stated, “Most of the oil and gas jobs in southeast New Mexico are at risk,” if the animal is listed as endangered. Mr. Pearce presented no information supporting his claim, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which manages endangered species, has stated that it is “absolutely not true” that lizard protection will inhibit oil and gas development.2 Oil and gas drilling is a significant economic activity in the Permian Basin of southeast New Mexico and west Texas, and the region is one of the largest domestic producers of fossil fuel in the United States.3 However, the range of dunes sagebrush lizard covers approximately 4 749,000 acres, or less than 2 percent of the 39.6 million-acre Permian Basin. 1 Information about the conservation status of dune sagebrush lizard is available at: http://ecos.fws.gov/ speciesProfile/profile/speciesProfile.action?spcode=C03J 2 R. Romo, “Lizard listing at center of debate,” Albuquerque Journal, 28 April 2011; also see A.