Hats, Handwraps and Headaches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Boxing Council Ratings

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL R A T I N G S RATINGS AS OF SEPTEMBER - 2018 / CLASIFICACIONES DEL MES DE SEPTIEMBRE - 2018 WORLD BOXING COUNCIL / CONSEJO MUNDIAL DE BOXEO COMITE DE CLASIFICACIONES / RATINGS COMMITTEE WBC Adress: Riobamba # 835, Col. Lindavista 07300 – CDMX, México Telephones: (525) 5119-5274 / 5119-5276 – Fax (525) 5119-5293 E-mail: [email protected] RATINGS RATINGS AS OF SEPTEMBER - 2018 / CLASIFICACIONES DEL MES DE SEPTIEMBRE - 2018 HEAVYWEIGHT (+200 - +90.71) CHAMPION: DEONTAY WILDER (US) EMERITUS CHAMPION: VITALI KLITSCHKO (UKRAINE) WON TITLE: January 17, 2015 LAST DEFENCE: March 3, 2018 LAST COMPULSORY: November 4, 2017 WBC SILVER CHAMPION: Dillian Whyte (Jamaica/GB) WBC INT. CHAMPION: VACANT WBA CHAMPION: Anthony Joshua (GB) IBF CHAMPION: Anthony Joshua (GB) WBO CHAMPION: Anthony Joshua (GB) Contenders: WBO CHAMPION: Joseph Parker (New Zealand) WBO CHAMPION:WBO CHAMPION: Joseph Parker Joseph (New Parker Zealand) (New Zealand) 1 Dillian Whyte (Jamaica/GB) SILVER Note: all boxers rated within the top 15 are 2 Luis Ortiz (Cuba) required to register with the WBC Clean 3 Tyson Fury (GB) * CBP/P Boxing Program at: www.wbcboxing.com 4 Dominic Breazeale (US) Continental Federations Champions: 5 Tony Bellew (GB) ABCO: 6 Joseph Parker (New Zealand) ABU: Tshibuabua Kalonga (Congo/Germany) BBBofC: Hughie Fury (GB) 7 Agit Kabayel (Germany) EBU CISBB: 8 Dereck Chisora (GB) EBU: Agit Kabayel (Germany) 9 Charles Martin (US) FECARBOX: 10 FECONSUR: Adam Kownacki (US) NABF: Oscar Rivas (Colombia/Canada) 11 Oscar Rivas (Colombia/Canada) NABF OPBF: Kyotaro Fujimoto (Japan) 12 Hughie Fury (GB) BBB C 13 Bryant Jennings (US) Affiliated Titles Champions: Commonwealth: Joe Joyce (GB) 14 Andy Ruiz Jr. -

This Is a Terrific Book from a True Boxing Man and the Best Account of the Making of a Boxing Legend.” Glenn Mccrory, Sky Sports

“This is a terrific book from a true boxing man and the best account of the making of a boxing legend.” Glenn McCrory, Sky Sports Contents About the author 8 Acknowledgements 9 Foreword 11 Introduction 13 Fight No 1 Emanuele Leo 47 Fight No 2 Paul Butlin 55 Fight No 3 Hrvoje Kisicek 6 3 Fight No 4 Dorian Darch 71 Fight No 5 Hector Avila 77 Fight No 6 Matt Legg 8 5 Fight No 7 Matt Skelton 93 Fight No 8 Konstantin Airich 101 Fight No 9 Denis Bakhtov 10 7 Fight No 10 Michael Sprott 113 Fight No 11 Jason Gavern 11 9 Fight No 12 Raphael Zumbano Love 12 7 Fight No 13 Kevin Johnson 13 3 Fight No 14 Gary Cornish 1 41 Fight No 15 Dillian Whyte 149 Fight No 16 Charles Martin 15 9 Fight No 17 Dominic Breazeale 16 9 Fight No 18 Eric Molina 17 7 Fight No 19 Wladimir Klitschko 185 Fight No 20 Carlos Takam 201 Anthony Joshua Professional Record 215 Index 21 9 Introduction GROWING UP, boxing didn’t interest ‘Femi’. ‘Never watched it,’ said Anthony Oluwafemi Olaseni Joshua, to give him his full name He was too busy climbing things! ‘As a child, I used to get bored a lot,’ Joshua told Sky Sports ‘I remember being bored, always out I’m a real street kid I like to be out exploring, that’s my type of thing Sitting at home on the computer isn’t really what I was brought up doing I was really active, climbing trees, poles and in the woods ’ He also ran fast Joshua reportedly ran 100 metres in 11 seconds when he was 14 years old, had a few training sessions at Callowland Amateur Boxing Club and scored lots of goals on the football pitch One season, he scored -

On Modernity, Identity and White-Collar Boxing. Phd

From Rookie to Rocky? On Modernity, Identity and White-Collar Boxing Edward John Wright, BA (Hons), MSc, MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. September, 2017 Abstract This thesis is the first sociological examination of white-collar boxing in the UK; a form of the sport particular to late modernity. Given this, the first research question asked is: what is white-collar boxing in this context? Further research questions pertain to social divisions and identity. White- collar boxing originally takes its name from the high social class of its practitioners in the USA, something which is not found in this study. White- collar boxing in and through this research is identified as a practice with a highly misleading title, given that those involved are not primarily from white-collar backgrounds. Rather than signifying the social class of practitioner, white-collar boxing is understood to pertain to a form of the sport in which complete beginners participate in an eight-week boxing course, in order to compete in a publicly-held, full-contact boxing match in a glamorous location in front of a large crowd. It is, thus, a condensed reproduction of the long-term career of the professional boxer, commodified for consumption by others. These courses are understood by those involved to be free in monetary terms, and undertaken to raise money for charity. As is evidenced in this research, neither is straightforwardly the case, and white-collar boxing can, instead, be understood as a philanthrocapitalist arrangement. The study involves ethnographic observation and interviews at a boxing club in the Midlands, as well as public weigh-ins and fight nights, to explore the complex interrelationships amongst class, gender and ethnicity to reveal the negotiation of identity in late modernity. -

Boxing Edition

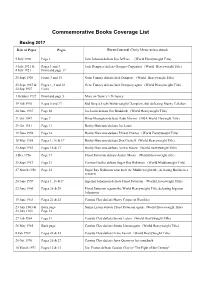

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

Ranking As of Dec. 10, 2016

Ranking as of Dec. 10, 2016 HEAVYWEIGHT JR. HEAVYWEIGHT LT. HEAVYWEIGHT (Over 201 lb)(Over 91,17 kg) (200 lb)(90,72 kg) (175 lb)(79,38 kg) CHAMPION CHAMPION CHAMPION JOSEPH PARKER NZ OLEKSANDR USYK UKR ANDRE WARD USA 1. David Haye UK 1. Noel Gevor (International) ARM 1. Sergey Kovalev (Sup. Champ.) RUS 2. Hughie Fury (Int-Cont.) UK 2. Mairis Briedis LAT 2. Dominic Böesel (Int-Cont) GER 3. Wladimir Klitschko UKR 3. Firat Arslan (WBO Europe) GER 3. Artur Beterbiev RUS 4. Jarrell Miller (NABO) USA 4. Krzysztof Glowacki POL 4. Robert Stieglitz GER 5. Andy Ruiz USA 5. Kevin Lerena SA 5. Erik Skoglund DEN 6. David Price UK 6. Krzysztof Wlodarczyk POL 6. Olexander Gvozdyk UKR 7. Tom Schwarz (WBO Youth) GER 7. Damir Beljo BA 7. Sean Monaghan USA 8. Edmund Gerber KAZ 8. Michael Hunter (NABO) USA 8. Isidro Ranoni Prieto (Latino) PAR 9 . Kubrat Pulev BUL 9. Maxim Vlasov RUS 9. Marcus Browne USA 10. Andrey Fedosov USA 10. Rakhim Chakhkiev RUS 10. Enrico Koelling GER 11. Izuagbe Ugonoh NIG 11. Thabiso Mchunu SA 11. Richard Baranyi (WBO Europe) HUN 12. Christian Hammer (WBO Europe) GER 12. Dmitry Kudryashov RUS 12. Mike Lee USA 13. Michael Wallisch GER 13. Imre Szello (Int-Cont) HUN 13. Vyacheslav Shabranskyy UKR 14. Andrzej Wawrzyk POL 14. Michal Cieslak POL 14. Joe Smith, Jr. USA 15. Andriy Rudenko UKR 15. Olanrewaju Durodola NIG 15. Igor Mikhalkin RUS ** CHAMPIONS CHAMPIONS CHAMPIONS VACANT WBA VACANT WBA ANDRE WARD WBA ANTHONY JOSHUA IBF MURAT GASSIEV IBF ANDRE WARD IBF DEONTAY WILDER WBC VACANT WBC ADONIS STEVENSON WBC SUP. -

Snips and Snipes 8 February 2018 the Threat That the IOC May Drop Boxing from the 2020 Olympic Games Should Come As No Surprise

Snips and Snipes 8 February 2018 The threat that the IOC may drop boxing from the 2020 Olympic Games should come as no surprise. For a few years now the AIBA which has responsibility for administrating International “amateur” boxing-but let’s not kid ourselves the Olympics Games are no longer for amateurs-have too long been focusing on making money rather than developing the sport. For a few years they have through the WSB and other initiatives helped make the transition from AIBA to professional boxing easier for elite boxers. However they have failed to tackle the quality of judging and refereeing and have failed to put in place and to police internal controls leaving themselves open to allegations of mismanagement and profligacy taking the organisation to the edge of bankruptcy. The criticism over their handling of boxing at the Rio Olympics had already put them under the IOC spotlight and then they went and shot themselves in the foot over the appointment of an interim President . They selected a man who has been sanctioned by the United States Treasury Department for alleged links to a major “transnational criminal organisation”. I can almost imagine the conversation “We need an interim President let’s appoint Gafur Rakhimov” with one voice saying “ isn’t he sanctioned by the United States Treasury Department for alleged link to a major “transnational criminal organisation”. “Yes sounds just the man for the job”! A ban from the Olympics would be a huge blow for boxing’s prestige but it is more difficult to decide whether it would have any repercussions for professional boxing. -

1607 WBO Ranking As of July 2016.Xlsx

Ranking as of July 27, 2016 HEAVYWEIGHT JR. HEAVYWEIGHT LT. HEAVYWEIGHT (Over 201 lb)(Over 91,17 kg) (200 lb)(90,72 kg) (175 lb)(79,38 kg) CHAMPION CHAMPION CHAMPION TYSON FURY UK KRZYSZTOF GLOWACKI POL SERGEY KOVALEV (Sup. Champ) RUS 1. Joseph Parker (Oriental) NZ 1. Oleksandr Usyk (Int-Cont.) UKR 1. Dominic Böesel (Inter-Continental) GER 2. Wladimir Klitschko (Sup. Champion) UKR 2. Noel Gevor (International) ARM 2. Andre Ward USA 3. Andy Ruiz USA 3. Thomas Williams, Jr. USA 3. Sean Monaghan (NABO) USA 4. David Haye UK 4. Damir Beljo (WBO Europe) BA 4. Artur Beterbiev RUS 5. Hughie Fury (Int-Cont.) UK 5. Mairis Briedis LAT 5. Erik Skoglund DEN 6. Michael Wallisch (WBO Europe) GER 6. Micki Nielsen DEN 6. Robert Stieglitz GER 7. Jarrell Miller (NABO) USA 7. Firat Arslan GER 7. Callum Smith UK 8. Alexander Ustinov RUS 8 . Krzysztof Wlodarczyk POL 8. Marcus Browne USA 9. Edmund Gerber KAZ 9. Pablo O. Natalio Farias (Latino) ARG 9. Olexander Gvozdyk UKR 10. Tom Schwarz (WBO Youth) GER 10. Dmytro Kucher UKR 10. Isidro Ranoni Prieto (Latino) PAR 11. Kubrat Pulev BUL 11. Michael Hunter (NABO) USA 11. Igor Mikhalkin RUS 12. David Price UK 12. Murat Gassiev RUS 12. Enrico Koelling GER 13. Izuagbe Ugonoh (WBO Africa) NIG 13. Maxim Vlasov RUS 13. Alexander Brand COL 14. Andrey Fedosov USA 14. Mateusz Masternak POL 14. Joe Smith, Jr. USA 15. Arthur Spilka POL 15. Thabiso Mchunu SA 15. Chad Dawson USA ** Ian Lewison (Asia Pacific) UK ** CHAMPIONS CHAMPIONS CHAMPIONS TYSON FURY WBA DENIS LEBEDEV WBA SERGEY KOVALEV WBA ANTHONY JOSHUA IBF DENIS LEBEDEV IBF SERGEY KOVALEV IBF DEONTAY WILDER WBC TONY BELLEW WBC ADONIS STEVENSON WBC SUP. -

Tyson Fury BBC SPOTY Furore Could Have Been Avoided – They Should Have Chosen Anthony Crolla

BBC SPOTY Tyson Fury Furore could have been avoided Item Type Article Authors Randles, David Citation Randles, D. (2015). BBC SPOTY Tyson Fury Furore could have been avoided. Vice Sports. Retrieved from https:// sports.vice.com/en_uk/article/bbc-spoty-tyson-fury-furore- could-have-been-avoided-they-should-have-chosen-anthony- crolla Publisher Vice Sports Download date 30/09/2021 05:17:40 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/618221 Tyson Fury BBC SPOTY furore could have been avoided – they should have chosen Anthony Crolla By David Randles - @davidrandles It will be interesting to see the table plan for the BBC Sports Personality of the Year awards. While steps will be taken to keep Tyson Fury away from Jessica Ennis-Hill, it may also be wise to put Greg Rutherford at the opposite end of the room to the recently crowned heavyweight champion of the world. It was Fury’s sexist comments about Ennis-Hill, combined with his forthright views aligning homosexuality and pedophilia, that riled Rutherford enough for the Olympic long jump champion to withdraw from the SPOTY 2015 running before changing his mind. Joining the chorus of condemnation for Fury are Northern Ireland’s largest gay rights group the Rainbow Project, who this week labeled his comments as ‘extremely callous’ and ‘erroneous’. In response to Fury’s insistence that a woman’s place is ‘in the kitchen or on her back’, feminist group Fight4Equality has blasted the self-titled Gypsy King’s ‘neanderthal worldview’ insisting Fury ‘should not be feted as a role model for young people.’ Both groups will be joined by other LGBT campaigners outside Belfast’s SSE Arena on Sunday evening to picket the BBC, angry that the show will go on despite vocal public opposition to Fury’s involvement. -

Badou Jack, Lucian Bute & James Degale Media

BADOU JACK, LUCIAN BUTE & JAMES DEGALE MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL TRANSCRIPT Leonard Ellerbe Good morning everyone. It’s a bright, sunny, beautiful day here in Las Vegas. Thank you all for joining the call today. I just want to go over a few fight facts real quickly. Tickets are on sale now, and they start as low as $25. They can be purchased online at Ticketmaster and all Ticketmaster locations. Our event will be live on SHOWTIME at 10 p.m. ET/7 p.m. PT We’ll be bringing you a double header of super middleweight title fights. Our event is promoted by Mayweather Promotions, in association with Interbox and Matchroom Boxing. The main event will feature Badou Jack versus Lucian Bute for the WBC Super Middleweight World Championship. Also on the card will be another very exciting televised bout. It will be featuring the IBF Super Middleweight Champion, James DeGale. DeGale will be fighting his mandatory challenger, Rogelio Medina. And the winners, all four fighters, have agreed to meet in a Super Middleweight Unification fight later this year. Well first up I’d like to introduce Lucian Bute. He comes to us with a 32 and 3 record with 25 big knockouts. He’s fighting out of Montreal, Canada by way of Romania. He’s a former IBF with nine title defenses between 2007 and 2012. His most recent performance against James DeGale was a very exciting bout and the fans were very impressed and earned him the right for this title shot. So without further ado, I’d like to introduce Lucian Bute. -

Froch Takes Majority Decision Over Johnson to Retain Crown and Advance to Super Six Final

Froch takes majority decision over Johnson to retain crown and advance to Super Six final ATLANTIC CITY– Carl Froch vaulted into the final of the Super Six world Super Middleweight tournament majority decision over Glen Johnson at the Adrian Phillips Ballroom inside of Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City. Not only does Froch advance to face WBA King Andre Ward but he retained his WBC crown in the process. After a non discript first round, Johnson started to up the pressure in round two as he came forward and landed a big over hand right. Froch had a good beginning of round three as he dipped in and out landing some swift combination’s. In the latter part of the round Johnson landed some nice right back that sent Froch back on his heels. Round four saw Froch box and move in a similar style to his wipe out points victory over Arthur Abraham where he seemed to have his timing down by landing solid combination’s while on the back pedal. Froch had a solid round six by continuing to land three punch combination’s that was sandwiched in between a big right hand that Johnson landed on the ropes. Round seven was a terrific back and forth battle as Johnson book-ended the round with two big right hands but Froch got some of his own work done as they went back and forth on the ropes. Round eight was a crowd pleasing round to say the least as the two traded bombs to show off their granite chin’s. -

Fredag Sendes World Boxing Super Series-Finalen På Viasat 4

27-09-2018 15:16 CEST Fredag sendes World Boxing Super Series-finalen på Viasat 4 Det blir en spektakulær boksekveld når finalen i super mellomvekstklassen i World Boxing Super Series skal avgjøres. Hele stevnet, inkludert storkampen mellom Groves og Smith, sendes fredag kl. 20.00 på Viasat 4 og Viaplay. Finalen blir et helbritisk oppgjør mellom George Groves (28-3, 20 KOs) fra Hammersmith, London og Callum Smith (24-0, 17 KOs) fra Liverpool. Begge bokserne er klare for det storslåtte oppgjøret de har kjempet seg frem til gjennom første sesong av World Boxing Super Series. Se innebygd innhold her - Denne turneringen er den eneste av sitt slag, og den har virkelig fanget publikum. Å vinne denne kampen vil være høydepunktet i karrieren min, sier Groves i en pre-fight dokumentar som kan ses på Viafree. I den samme dokumentaren sier hans motstander at han også vil gjøre alt for å vinne fredagens kamp. - Jeg har drømt om å bli verdensmester siden den dagen jeg ble proffbokser. Endelig er kampen jeg har ventet på her, forteller Callum Smith i dokumentaren. De to britene kjemper om Muhammad Ali-troféet, WBA Super World Championship, WBC Diamond-beltet og Ring Magazine-beltet. Stevnes som sendes direkte fra Jeddah, Saudi-Arabia kommenteres av tidligere proffbokser Thomas Hansvoll. Stevnet sendes fredag 28. september fra kl. 20:00 på Viasat 4 og Viaplay. Nordic Entertainment Group (NENT Group) er Nordens ledende underholdningsleverandør. Vi underholder millioner av mennesker hver dag med våre strømmetjenester, TV-kanaler og radiostasjoner, og våre produksjonsselskaper skaper nytt og spennende innhold for medieselskaper i hele verden. -

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO JESUS MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS of JANUARY Based on Results Held from 01St to January 29Th, 2021

2021 Ocean Business Plaza Building, Av. Aquilino de la Guardia and 47 St., 14th Floor, Office 1405 Panama City, Panama Phone: +507 203-7681 www.wbaboxing.com WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO JESUS MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF JANUARY Based on results held from 01st to January 29th, 2021 INTERIM CHAIRMAN MEMBERS CARLOS CHAVEZ - VENEZUELA WON KIM - KOREA [email protected] THOMAS PUTZ - GERMANY VICE CHAIRMAN OCTAVIO RODRIGUEZ - PANAMA AURELIO FIENGO - PANAMA RAUL CAIZ JR - USA [email protected] FERLIN MARSH - NEW ZEALAND Over 200 Lbs / 200 Lbs / 175 Lbs / HEAVYWEIGHT CRUISERWEIGHT LIGHT HEAVYWEIGHT Over 90.71 Kgs 90.71 Kgs 79.38 Kgs WBA-WBO-IBF SUPER CHAMPION:ANTHONY JOSHUA GBR WBA SUPER CHAMPION: ARSEN GOULAMIRIAN FRA WBA SUPER CHAMPION: DMITRY BIVOL RUS WORLD CHAMPION: RYAD MERHY BEL WORLD CHAMPION: JEAN PASCAL CAN WBA GOLD CHAMPION: ROBERT HELENIUS FIN WBA GOLD CHAMPION: ALEXEY EGOROV RUS CHAMPION IN RECESS: MAHMOUD CHARR LIB WBC: TYSON FURY WBC: ILUNGA MAKABU WBC: ARTUR BETERBIEV IBF: MAIRIS BRIEDIS WBO: VACANT IBF: ARTUR BETERBIEV WBO: VACANT 1. TREVOR BRYAN INTERIM CHAMP USA 1. YUNIEL DORTICOS CUB 1. ROBIN KRASNIQI INTERIM CHAMP KOS 2. OLEKSANDR USYK UKR 2. KEVIN LERENA RSA 2. JOSHUA BUATSI INT GHA 3. BOGDAN DINU ROU 3. RICHARD RIAKPORHE I/C GBR 3. BLAKE CAPARELLO OCEANIA AUS 4. DEONTAY WILDER USA 4. MIKE WILSON NABA USA 4. GILBERTO RAMIREZ MEX 5. LUIS ORTIZ CUB 5. AHMED ELBIALI EGY 5. CHARLES FOSTER NABA USA 6. ANDY RUIZ JR USA 6. DEON NICHOLSON USA 6. DOMINIC BOESEL GER 7. ADAM KOWNACKI POL 7. RAPHAEL MURPHY USA 7.