Jeremy Farrar, Director, Wellcome Trust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sustainable Innovation Fund: Round 1 (Temporary Framework)

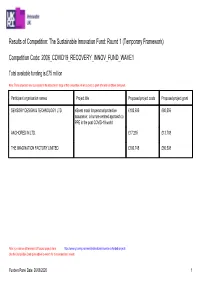

Results of Competition: The Sustainable Innovation Fund: Round 1 (Temporary Framework) Competition Code: 2006_COVID19_RECOVERY_INNOV_FUND_WAVE1 Total available funding is £75 million Note: These proposals have succeeded in the assessment stage of this competition. All are subject to grant offer and conditions being met. Participant organisation names Project title Proposed project costs Proposed project grant SENSORY DESIGN & TECHNOLOGY LTD eScent mask for personal protective £100,695 £80,556 assurance: a human-centred approach to PPE in the post COVID-19 world ANCHORED IN LTD. £17,235 £13,788 THE IMAGINATION FACTORY LIMITED £100,748 £80,598 Note: you can see all Innovate UK-funded projects here: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/innovate-uk-funded-projects Use the Competition Code given above to search for this competition’s results Funders Panel Date: 26/08/2020 1 Project description - provided by applicants The panic around coronavirus has resulted in global demand for masks. The trauma associated with COVID-19 has led to the deaths of many healthcare staff. Recent research published in Cell \[1\] suggests that SARs-CoV-2 infects cells of the respiratory tract with the nose being the dominant site from which lung infections begin. This opens new directions for future intranasal wearable therapeutic strategies that could reduce transmission of COVID-19 and other coronaviruses in the nose. The challenge of the pandemic requires imaginative collaborations between disciplines and could benefit from an innovation that enhances the emotional and mental wellbeing of the population. eScent is engineering a new movement in wearable, sustainable voice-activated scent dispensing. In partnership with IF/Anchored-IN, we are commercializing a product that seeks to calm people with a soothing aromatic atmosphere to boost the immune system, whilst improving on current protection provided by FPP3 masks. -

Jeremy Farrar

FEATURE The BMJ THE BMJ INTERVIEW BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.n459 on 19 February 2021. Downloaded from [email protected] Cite this as: BMJ 2021;372:n459 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n459 Jeremy Farrar: Make vaccine available to other countries as soon as Published: 19 February 2021 our most vulnerable people have received it The SAGE adviser and Wellcome Trust director tells Mun-Keat Looi how the UK government acted too slowly against the pandemic, about the perils of vaccine nationalism, and why he is bullish about controlling covid variants Mun-Keat Looi international features editor “Once the UK has vaccinated our most vulnerable among healthcare workers. We had no human communities and healthcare workers we should make immunity, no diagnostics, no treatment, and no vaccines available to other countries,” insists the vaccines. infectious disease expert Jeremy Farrar. This could Every country should have acted then. Singapore, avert further public health and economic disaster, China, and South Korea did. Yet most of Europe and he says, describing it as “enlightened self-interest, North America waited until the middle of March, and as well as the right ethical thing to do.” that defined the first wave. Countries including the In April 2020, soon after the first UK lockdown began, UK were unwilling to act early, before they felt Farrar predicted that the UK would have one of the comfortable; were unwilling to go deeper than they worst covid-19 death rates in Europe. As a member thought they had to; and were unwilling to keep of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies restrictions in place for as long as was needed. -

“Taking Back Control”: Whose, and Back to When? Logie Barrow

THE LONG READ “Taking back Control”: Whose, and Back to When? Logie Barrow Logie Barrow (Bremen) interprets the Conservative rom around 1700, Britain’s political Party’s approach to Brexit as a response to the F culture (unwritten constitution; self-image traumatic loss of control suffered by the party as moderate; other features so familiar to 1st- during the 1940s-1970s. In the longer term, the year students), often hard-fought but never Conservative Party has often attained and held destroyed, has been cushioned in economic onto power by promoting class-integrative myths, success. such as national greatness. Thus, Brexit may be seen as an attempt to contain class struggle by o indulge in reductionism: over promising an enlarged ‘national cake’ to be shared T generations, the Tories have helped in by all, at the cost of external others. Barrow British capitalism as demagogues and enforcers. argues that the Tories’ have been cushioned from But, had too much of the economic content of the impact of their often misguided economic their demagogy become reality, it would have policies by Britain’s economic power, but that the harmed overall profitability and stability. Such country’s radically altered position in a globalised has repeatedly been the paradox since the mid- th world makes this strategy more difficult to pull off. 19 century. Now, for the first time, political He further shows that the Conservatives’ handling triumph is knocking on the economic door. The of the Covid-19 crisis may be seen as symptomatic main reasons for this are sometimes centuries of the party’s neoliberal agenda, which includes old. -

Financing Vaccines for Global Health Security

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES FINANCING VACCINES FOR GLOBAL HEALTH SECURITY Jonathan T. Vu Benjamin K. Kaplan Shomesh Chaudhuri Monique K. Mansoura Andrew W. Lo Working Paper 27212 http://www.nber.org/papers/w27212 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 May 2020 We thank Ellen Carlin, Doug Criscitello, Margaret Crotty, Narges Dorratoltaj, Per Etholm, Jeremy Farrar, Nimah Farzan, Mark Feinberg, Jose-Maria Fernandez, John Grabenstein, Peter Hale, Richard Hatchett, Peter Hotez, Daniel Kaniewski, Adel Mahmoud, Mike Osterholm, May 2020 Farrar, Nimah Kevin Outterson, Chi Heem Wong, CEPI leadership, and two reviewers and the editor for helpful comments and discussion, and Jayna Cummings for editorial assistance. Research support from the MIT Laboratory for Financial Engineering and the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University is gratefully acknowledged. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors only, and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of any institution or agency, any of their affiliates or employees, any of the individuals acknowledged above, or the National Bureau of Economic Research. Funding support from the MIT Laboratory for Financial Engineering is gratefully acknowledged, but no direct funding was received for this study and no funding bodies had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of this manuscript. The authors were personally salaried by their institutions during the period of writing (though no specific salary was set aside or given for the writing of this manuscript). At least one co-author has disclosed a financial relationship of potential relevance for this research. -

Oxford Medicine

Oxford Medicine THE NEWSLETTER OF THE OXFORD MEDICAL ALUMNI OXFORD MEDICINE • DECEMBER 2019 Courtesy of Ludwig Cancer Research of Ludwig Cancer Courtesy The Regius Professor Sir Tingewick is Does reflects on Peter Ratcliffe 80! Developmental 45 years in FRS, Nobel Dyslexia Really medicine Laureate Exist? 2 / OXFORD MEDICINE DECEMBER 2019 President’s Piece Welcome to the December Sir William Osler’s Centenary commemorations will issue of Oxford Medicine, the continue throughout the year in Oxford and beyond. newsletter for Oxford Medical The Osler Club is the first of a number of thriving Alumni (OMA) who have postgraduate Oxford medical societies we plan to feature. trained, taught, or worked at Professor Terence Ryan summarises this year’s five Osler Oxford. Professor John Morris, Club seminars exploring the Oslerian theme ‘For Health OMA president for the past and Wellbeing, Science and Humanities are one’. six years, handed the baton Tingewick is 80 this year. In 2019, as in 1939, Tingewick to me in September. It is a Dr Lyn Williamson, is still the most inclusive Oxford clinical student society. OMA President daunting task to take over from This year, every first year clinical student took part - someone so beloved and so that is 165! The show was a triumph of teamwork and respected, who has taught anatomy to generations talent. The legacy of camaraderie will last a lifetime - as of Oxford students and postgraduates, and shaped witnessed by the 80th anniversary celebrations. Dr Derek the preclinical school for many years. With his Roskell, Senior Tingewick Member for 25 years adds his characteristic kindness and wisdom, he said: ‘You will be fine - and I will be there to advise you’. -

Trustees' Annual Report and Financial Statements 31 March 2016

THE FRANCIS CRICK INSTITUTE LIMITED A COMPANY LIMITED BY SHARES TRUSTEES’ ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 31 MARCH 2016 Charity registration number: 1140062 Company registration number: 6885462 The Francis Crick Institute Accounts 2016 CONTENTS INSIDE THIS REPORT Trustees’ report (incorporating the Strategic report and Directors’ report) 1 Independent auditor’s report 12 Consolidated statement of financial activities 13 Balance sheets 14 Cash flow statements 15 Notes to the financial statements 16 1 TRUSTEES’ REPORT (INCORPORATING THE STRATEGIC REPORT AND DIRECTORS’ REPORT) The trustees present their annual directors’ report together with the consolidated financial statements for the charity and its subsidiary (together, ‘the Group’) for the year ended 31 March 2016, which are prepared to meet the requirements for a directors’ report and financial statements for Companies Act purposes. The financial statements comply with the Charities Act 2011, the Companies Act 2006, and the Statement of Recommended Practice applicable to charities preparing their accounts in accordance with the Financial Reporting Standard applicable in the UK (FRS102) effective 1 January 2015 (Charity SORP). The trustees’ report includes the additional content required of larger charities. REFERENCE AND ADMINISTRATIVE DETAILS The Francis Crick Institute Limited (‘the charity’, ‘the Institute’ or ‘the Crick) is registered with the Charity Commission, charity number 1140062. The charity has operated and continues to operate under the name of the Francis Crick -

View Questions Tabled on PDF File 0.16 MB

Published: Friday 23 April 2021 Questions tabled on Thursday 22 April 2021 Includes questions tabled on earlier days which have been transferred. T Indicates a topical oral question. Members are selected by ballot to ask a Topical Question. † Indicates a Question not included in the random selection process but accepted because the quota for that day had not been filled. N Indicates a question for written answer on a named day under S.O. No. 22(4). [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Monday 26 April Questions for Written Answer 1 Deidre Brock (Edinburgh North and Leith): To ask the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office, how much his Department has spent on social media advertising aimed solely or mainly at individuals, businesses or organisations resident, working or operating in Scotland in each month since June 2017. (185930) 2 Dan Carden (Liverpool, Walton): To ask the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office, whether a requirement for (a) company identifiers and (b) spend data is planned to be included in upcoming public procurement reforms. (186006) 3 Caroline Lucas (Brighton, Pavilion): To ask the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office, pursuant the Answer of 29 March 2021 to Question 172053 on Gender Based Violence: Victim Support Schemes, and with reference to the Green Paper Transforming Public Procurement, if he will publish a White Paper containing criteria setting out when it is appropriate for grant funding to be used for specialist provision for Violence Against Women and Girls services and for procurement rules to not apply. -

Briefing Note 119 - COVID-19 Guidance As at 13:00 Monday 9Th November 2020

Edition 119 Briefing Note 119 - COVID-19 Guidance As at 13:00 Monday 9th November 2020 A. Summary of UK activities: period ending Monday 9th November NATIONAL RESTRICTIONS APPLY IN ENGLAND UNTIL 02/12/2020 Date Monday 2nd November 2020 01 Prime Minister’s oral statement on COVID-19 to Parliament [2nd November 2020] 02 Government announces additional support for self-employed across the UK 03 Half a million daily testing capacity reached on 31st October Tuesday 3rd November 2020 01 Liverpool to be regularly tested in whole city COVID-19 testing pilot 02 COVID-19 grants available to help England’s ports and fishing industry 03 New national restrictions that apply in England from 5th November Wednesday 4th November 2020 01 £134 million allocated to help UK businesses build back greener 02 Updated guidance issued to protect clinically extremely vulnerable people 03 Information for general medical practices on providing COVID-19 testing 04 Impact of national restrictions on education, childcare & children’s social care 05 Prime Minister’s oral statement on COVID-19 to Parliament [4th November 2020] 06 New national measures affecting caravan and park home sites Thursday 5th November 2020 01 National restrictions poster – promotional material [England] 02 Furlough scheme extended until end of March 2021 and support for self-employed 03 Self-Employment Income Support Scheme extension to April 2021: guidance 04 Extension of Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme to January 2021: interim guidance 05 Prime Minister’s oral statement on COVID-19 at press conference [5th November 2020] HANDS FACE SPACE Friday 6th November 2020 01 New protection for renters during new National restrictions for England Saturday 7th November 2020 01 Making a childcare bubble with another household Sunday 8th November 2020 01 Measures to protect England from new COVID-19 strain extended to cover hauliers B. -

COVID-19 Vaccine Development, Strategy and Implementation

Symposium: Vaccines and Global Health: COVID-19 Vaccine Development, Strategy and Implementation The Program in Vaccine Education at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians & Surgeons’ mission is to educate medical students and to inform health care professionals, public health experts, academic, government and industry researchers, policy makers, global health non-governmental organizations, journalists, and the general public as to the cutting-edge advances and challenges in modern vaccine development. The Columbia University convenors are Drs. Lawrence Stanberry (Co-Director, PVE), Philip LaRussa (Co-Director, PVE), Wilmot James (Associate Director, PVE), and Marc Grodman (Special Advisor, PVE). We have put together a group of 25 outstanding speakers who have been intimately involved with all aspects of COVID-19 vaccine development, strategy, and implementation. We are delighted to present this five-day virtual symposium at the cusp of the world’s transition to controlling the COVID-19 pandemic. Monday, February 22 National, Regional and Global Response to an Unprecedented Challenge 12:00-12:10 Welcome: Lee Bollinger, JD – President, Columbia University 12:10-12:15 Moderator: Lawrence R. Stanberry, MD, PhD – Director of the Programs in Global Health, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons 12:15-12:45 Keynote: Sir Jeremy Farrar, BSc, MBBS, PhD – Director, Wellcome Trust The Role of the Wellcome Trust in COVID-19 Vaccine Preparedness 12:45-1:30 Speakers: - Shabir Madhi, MBChB, MMed, FCPaeds PhD – Professor of Vaccinology, University of the Witwatersrand – A South African perspective on vaccine preparedness and availability. - Nancy Messonnier, MD – Director, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, US CDC – A US CDC perspective on vaccine preparedness and availability. -

Meeting Schedule/Structure

Special isirv-AVG Virtual Conference on ‘Therapeutics for COVID-19’ Tuesday 6th - Thursday 8th October 2020 (12.00-16.00 GMT daily) Programme Tuesday 6 October 12:00-12:15 Welcome Alan Hay, Francis Crick Institute, London, UK & Frederick Hayden, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA, USA Introduction Jeremy Farrar, Wellcome Trust, London, UK Chairs TBC 12:15-12:40 COVID-19 Clinical Spectrum, Complications, and Coinfections Bin Cao, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing, China 12:40-13:00 COVID-19 Viral Replication Kinetics Malik Peiris, University of Hong Kong, HK SAR, China 13:00-13:20 COVID-19 Autopsy Findings Xiuwu Bian, China (TBC) 13:20-13:40 Immunopathogenesis of COVID-19 Peter Openshaw, Imperial College London, UK 13:40-14:00 Pathogenesis and Management of ARDS – Richard Wunderink, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA 14:00-14:10 Comfort Break 14:10-15:10 Chairs TBC Oral Abstract Session 1 4 x 15 minute presentations (including Q&A) 15:10-15:20 Close of Day 1 Poster Viewing Page 1 of 3 Wednesday 7 October Chairs TBC 12:00-12:20 SARS-CoV-2 Antiviral Targets Mark Denison (accepted in principle) 12:20-12:40 Pre-clinical Models for Downselecting Candidates Andres Pizzorno, International Center for Research in Infectious Diseases, Lyon, France 12:40-13:10 RECOVERY Trial and Strategies for Rapid Clinical Testing Peter Horby, Oxford, UK 13:10-13:30 Convalescent Plasma and Polyclonal Antibodies - Michael Joyner, Mayo Clinic, MN, USA 13:30-13:50 Monoclonal Antibodies Erica Saphire, La Jolla Institute for -

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2017 Programme

Global Agenda World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2017 Programme Davos-Klosters, Switzerland 17-20 January Programme Pillars Programme Icons Programme Co- Chairs Experience Webcast Session Frans van Houten, President and Chief Executive Officer, Royal Philips, Netherlands Immersive experiences across time, space and emotions made memorable by Interpretation Brian T. Moynihan, Chairman of the inspiring interactions and thought- Board and Chief Executive Officer, provoking settings On the record Bank of America Corporation, USA Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, Discover Sign-up required Documentary Filmmaker, SOC Films, Pakistan; Young Global Leader Engaging explorations of the conceptual breakthroughs of our time and their Helle Thorning-Schmidt, Chief transformative impact on society, industry Executive Officer, Save the Children and policy International, United Kingdom Meg Whitman, President and Chief Debate Executive Officer, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, USA Insightful exchanges bringing together diverse opinions and ideas on today's most relevant economic, scientific and political issues Collaborate Hands-on sessions where leaders from all backgrounds come together to shape solutions to the world's most pressing challenges World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2017 - Programme 2 Sunday 15 January 06.00 - 01.00 Registration - Mühlestrasse 6 - 7260 Davos Dorf 1 registration Registration Opens Pick up your badge as of Sunday 15 January at 06.00 at Registration located at Mühlestrasse 6. Please note that the Congress Centre opens on Monday 16 January -

Research Bodies Vow to Share Data on Zika

BMJ 2016;352:i877 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i877 (Published 11 February 2016) Page 1 of 1 News BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.i877 on 11 February 2016. Downloaded from NEWS Research bodies vow to share data on Zika Zosia Kmietowicz The BMJ Academic journals, charities, research funders, and institutes available to all, free of charge, as soon as is feasibly possible. have committed themselves to sharing data and results relevant Journal signatories have said that doing this would not preclude to the current Zika virus outbreak and future public health researchers from subsequently publishing papers in their titles. emergencies as rapidly and openly as possible. Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust and a signatory The organisations, including the Bill and Melinda Gates to the statement, said, “Research is an essential part of the Foundation, Médecins Sans Frontières, the US National response to any global health emergency. This is particularly Institutes of Health, and the UK health research charity the true for Zika, where so much is still unknown about the virus, Wellcome Trust, along with leading academic journals such as how it is spread, and the possible link with microcephaly. The BMJ, Nature, Science, and the New England Journal of “It’s critical that as results become available they are shared Medicine, have signed a joint declaration and hope that other rapidly in a way that is equitable, ethical, and transparent. This bodies will add their names to the statement in the coming will ensure that the knowledge gained is turned quickly into weeks. health interventions that can have an impact on the epidemic.” The statement is intended to ensure that any information that http://www.bmj.com/ might have value in combating the Zika outbreak is made on 27 September 2021 by guest.