An Analysis of a University's Potential Liability for Sexual Assualts Committed by Its Student Athletes Jenni E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

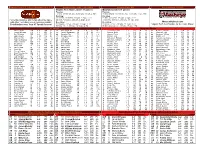

Maroonhelmet.Com

Virginia Tech (6-0, 3-0) vs. Maryland (4-2, 2-1) October 20th, 2005, 7:45 (ESPN) College Park, MD Byrd Stadium (51,500) Virginia Tech Stats Leaders (6 games) Maryland Leaders (6 games) Passing: Passing: 5 Vick, 73-107 (68.2%), 1,043 yds, 10 TDs, 2 INTs 14 Hollenbach, 113-173 (65.3%), 1,513 yds, 7 TD, 7 INT Rushing: Rushing: 32 Humes, 78 rushes, 325 yds, 4.2 ypc, 5 TD 44 Ball, 65 rushes, 346 yds, 5.4 ypc, 3 TD For recap, analysis, and to talk about the game 20 Imoh, 63 rushes, 254 yds, 4.0 ypc, 2 TD 8 Merrills, 72 rushes, 272 yds, 3.8 ypc, 4 TD with other Tech fans on our message boards! Receiving: Receiving: MaroonHelmet.com TechSideline.com: Your VT Sports Source! 87 Clownry, 16 rec., 299 yds, 18.7 ypc, 3 TD 18 Davis, 24 rec., 490 yds, 20.4 ypc, 3 TD Virginia Tech merchandise for the Hokie Nation 90 King, 15 rec. 188 yds, 12.5 ypc, 4 TD 85 Melendez, 24 rec., 361 yds, 15 ypc, 1 TD VT Roster Maryland Roster 1 Victor Harris DB 6-0 180 Fr. 44 John Candelas TB 6-0 211 Sr. 1 Henderson, Erin 6-3 233 LB FR 46 Peoples, Marvin 6-2 230 LB FR 2 Jimmy Williams CB 6-3 206 Sr. 45 Purnell Sturdivant LB 5-10 209 r-Fr. 2 Barnes, Kevin 6-1 172 CB FR 47 Clement, Jeff 6-2 235 DE FR 3 Ike Whitaker QB 6-4 200 Fr. -

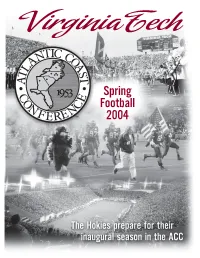

2004 Spring FB MG

Virginia Tech Spring Football 2004 Underclassmen To Watch 11 Xavier Adibi 42 James Anderson 59 Barry Booker 89 Duane Brown 96 Noland Burchette 61 Reggie Butler 44 John Candelas LB • r-Fr. LB • r-Jr. DT • r-Fr. TE • r-Fr. DE • r-So. OT • Jr. TB • Jr. 57 Tripp Carroll 37 Chris Ceasar 16 Chris Clifton 87 David Clowney Jud Dunlevy 49 Chris Ellis 28 Corey Gordon C • r-Fr. CB • r-So. SE • r-Jr. FL • So. PK • r-Fr. DE • r-Fr. FS • r-Fr. 77 Brandon Gore 9Vince Hall 27 Justin Hamilton John Hedge 18 Michael Hinton 32 Cedric Humes 19 Josh Hyman OG • r-So. LB • r-Fr. FL • r-Jr. PK • r-Fr. ROV • r-Fr. TB • r-Jr. SE • r-Fr. 20 Mike Imoh 90 Jeff King 43 John Kinzer 56 Jonathan Lewis 88 Michael Malone 52 Jimmy Martin 69 Danny McGrath TB • Jr. TE • r-Jr. FB • r-Fr. DT • Jr. SE • r-So. OT • Jr. C • r-So. 29 Brian McPherson 15 Roland Minor 66 Will Montgomery 72 Jason Murphy 46 Brandon Pace 58 Chris Pannell 50 Mike Parham CB • r-So. CB • r-Fr. OG • r-Jr. OG • r-Jr. PK • r-So. OT • r-Jr. C • r-So. 80 Robert Parker 99 Carlton Powell 83 Matt Roan 75 Kory Robertson 36 Aaron Rouse 71 Tim Sandidge 23 Nic Schmitt FL • r-So. DT • r-Fr. TE • r-Fr. DT • r-Fr. LB • r-So. DT • r-Jr. P • r-So. 55 Darryl Tapp 41 Jordan Trott 5 Marcus Vick 30 Cary Wade 24 D.J. -

IOWA FINAL FOUR TEAMS Iowa History

2010 IOWA BASKETBALL MEDIA GUIDE 2010 IOWA BASKETBALL MEDIA GUIDE IOWA FINAL FOUR TEAMS Iowa History 1954-55 (19-7 OVERALL, 11-3 BIG TEN) This years team won the Big Ten Championship and was Iowa’s first NCAA tourna- ment squad won an outright conference title (11-3) before finishing fourth in the national tournament. Coach Bucky O’Connor’s team became the first in Iowa history to average more than 80 points per game. Bill Logan led the Hawkeyes in scoring (15.9) and rebounding (11.0). Front (l to r): Augie Martel, Bill Seaberg, Les Hawthorne. Middle (l to r): Sharm Scheuerman, McKinley Davis, Doug Duncan, Bill Logan, Bill Schoof, Carl Cain, Roy Johnson. Back (l to r): Coach Bucky O’Connor, Tom Choules, Frank Sebolt, John Liston, Richard Ritter, Bob George, Jerry Ridley, Carter Crookham, Mgr. Bill Holman. 1955-56 (20-6 OVERALL, 13-1 BIG TEN) The “Fabulous Five” ‑‑ Carl Cain, Bill Logan, Sharm Scheuerman, Bill Schoof and Bill Seaburg ‑‑ were NCAA runners-up, dropping an 83-71 decision to No. 1-ranked San Francisco. Iowa lost its Big Ten opener before winning 13 consecutive games to take a second straight conference title. Cain was a first team all-American and Logan led the team in scoring and rebounding. Front (l to r): Norman Paul, Gene Pitts, Tom Payne, Bob George, Bill Logan, Bill Schoof, Carl Cain, Sharm Scheuerman, Bill Seaberg. Back (l to r): Tom Rohovit, Augie Martel, Jim McConnell, Gregg Schroeder, Paul Rausch, Frank Sebolt, Carter Crookham, Les Hawthorne, Coach Bucky O’Connor. -

WHY BRANDING CAN INCREASE a PROFESSIONAL ATHLETE's VALUE: a RATIONALE for DESIGNER ENGAGEMENT a Thesis Presented in Partial Fu

WHY BRANDING CAN INCREASE A PROFESSIONAL ATHLETE’S VALUE: A RATIONALE FOR DESIGNER ENGAGEMENT A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brandan Craft ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Master’s Examination Committee: Approved by Professor R. Brian Stone, Advisor Dr. Noel Mayo Advisor Peter Chan, PhD Graduate Program in Industrial, Interior, and Visual Communication Design Copyright by Brandan Craft 2008 ABSTRACT Brands allow consumers to make choices. They help them differentiate one individual, business, or product from the other by delivering a promise that leads to expectations and perceptions. The value of a brand is measured by this perception. What the consumer perceives a business to be, not the business’s perception, is that business’s brand. Designers play a large part in influencing this perception by creating brand identity systems that become the tangible expression of a business’s identity. There is an opportunity for designers to play a larger role in a business’s success by capitalizing on the increasing reliance on branding to assist in wealth generation. Professional athletes are small businesses. They are distinct individuals that ultimately rely on their fans to build wealth. The fan’s perception of an athlete, that athlete’s brand, influences the differentiation of one player from another. The decision to invest in the brand, whether it is to watch a game on television, buy tickets to the game, or purchase a player’s jersey after the game, rests on this perception. -

Cards Trump Both Aces Months, but the Two-Time MVP Isn't Paying Any Attention to Their Prognosis

Board will hear Pierce appeal, 5C • Tonight's prep football matchups, 6C Sibley on the American crow, 8C • The Gazette Spectacular season Friday A splendid summer October 4, 2002 of bass fishing c: coming to a close, 8C SPORTS www.gazetteonline.com PREPS COLLEGES PROS Voila! Kennedy like a new team ton scoreboard. Cougars block, tackle, A Cougar defense that had been riddled for 1,518 yards and 148 points in kick ... get first win its first four games disappeared into the soupy sky and the defense that ap By Jeff Dahn peared in its place came within 9 The Gazette CEDAR RAPIDS — There was a minutes of posting a shutout. touch of magic in the air at fog-shroud And reserve tailback Mike Russell ed Kingston Stadium Thursday night. popped out of a hat like a white rabbit to rush for 58 yards and Kennedy's lone touchdown in the third quarter, sending A Cedar Rapids Kennedy offense that Waterloo West back on its heels. AP photo Taken as a whole, the dash of magic C.R. KENNEDY 10 produced a 10-6 Kennedy win over Winning form WATERLOO WEST 6 West, the Cougars' first of the 2002 Yang Wei of China performs hadn't scored a point in 12 straight Mississippi Valley Conference season. Gazette photo by Kevin Wolf parallel bars Thursday In the quarters coming in watched as — poof! "We're starting the season over right Cedar Rapids Kennedy's Blake Fisher returns a punt against Waterloo West's Asian Games men's gymnas — 10 points materialized on the Kings • Turn to 5C: Kennedy Courtney Henry (33) and Dustin Schildgen Thursday at Kingston Stadium. -

Apparel,” American Apparel Proj- SENIOR NEWS REPORTER Ect Manager and Site Selector Scott Allen Was Arrested When Police Company Known for Mak- Tacee Webb Said

Mayor Kitty Piercy delivers second State of the City speech | 4 An independent newspaper at the University of Oregon www.dailyemerald.com SINCE 1900 | Volume 107, Issue 72 | Monday, January 9, 2006 Leaks damage campus buildings UO student Several campus buildings sprung leaks in recent storms, causing thousands of dollars in damage accused of BY NICHOLAS WILBUR Dana Winitzky each spent possessing NEWS REPORTER about two hours on New The EMU incurred about Year’s Eve vacuuming the $75,000 in damages after near- flood waters. ly 2.5 inches of water flooded Winitzky “popped” the sky- child porn into to east end of the 50-year- light floor to get to the two old building and dripped down inches of sitting water under James Adrian Raasch, 30, was several levels, ballooning and the tiles, Winitzky said. What arrested after a UO technician breaking the wooden floors in students now see is the result several places. of wooden tiles absorbing the found pornography on his laptop Five or six other buildings water, expanding and buckling were damaged, but Agate An- from the pressure. “We got the majority of the BY PARKER HOWELL nex, which requires about EDITOR IN CHIEF $25,000 to fix basement flood- sitting water, but the damage ing, and the EMU, are the two had already been done,” A University gradu- most costly. Winitzky said. ate student was arrest- Students’ incidental fees of- There are several large ed Wednesday morn- ten help pay for emergency re- bulges in the floor outside ing after Eugene police pairs, but because of the severi- of the EMU ticket office and found child pornogra- ty of the damage, the state’s two in the skylight room phy on a laptop com- insurance is expected to pay that stretch more than 12 feet puter he brought to a the majority of the bill. -

Gic Complete Manuscript Final

BE Sociology • globalization S T, KA “At a time when it is increasingly more difficult to find insightful and accessible work challenging the struc- H tural and ideological foundations of neoliberal economic savagery, The Global Industrial Complex: Systems N, of Domination provides a key resource for such a task. This is a wide ranging and thoughtful book that not N O only critically analyzes the deepening and myriad forms of global market authoritarianism but also offers the C E theoretical tools to challenge it. A must read for anyone concerned about the promise of a real democracy LL and the economic, political, and cultural forces subverting it.” A, AN —HENRY GIROUX, McMaster University and author of Beyond the Spectacle of Terrorism: Global Uncertainty and the Challenge of the New Media D MC “An excellent, well-researched, and richly informed compendium on the nature of global exploitation and LA power, a nourishing corrective to the vapid evasions we are usually fed.” R —MICHAEL PARENTI, author of The Face of Imperialism (2011) and God and His Demons (2010) EN The Global Industrial Complex: Systems of Domination, is a groundbreaking collection of essays by leading scholars from wide scholarly and activist backgrounds who examine the entangled array of contemporary industrial complexes—what the editors refer to as the “power complex”—that was first analyzed by C. Wright Mills in his 1956 classic work The Power Elite. In this new volume edited by Steven Best, Richard THE GLOBAL INDUS Kahn, Anthony J. Nocella II, and Peter McLaren, the power complex is conceived as co-constituted, interde- pendent, and imbricated systems of domination. -

Hokies in the NFL Draft

Carroll Dale Michael Vick Many Virginia Tech players have gone on to make their mark in the NFL Tech Players in the Pros The following former Hokies are either Andy Bowling ..................... Atlanta Falcons Eugene Chung ...............Philadelphia Eagles presently are or were a member of a National Kansas City Chiefs Football League team or competed in the Carl Bradley ........................ St. Louis Rams Indianapolis Colts United States Football League: Green Bay Packers Gene Breen .....................Green Bay Packers San Francisco 49ers (players in bold were Jacksonville Jaguars active as of June 1, 2006) Cornell Brown ...................Baltimore Ravens New England Patriots James AndersonAnderson ............ CarolinaCarolina PanthersPanthers KenKen BrownBrown ......................... Denver BroncosBroncos Billy ConatyConaty ........................Dallas Cowboys Buffalo Bills Antonio Banks ....................Oakland Raiders Robert Brown ..................Green Bay Packers Minnesota Vikings Ray Crittenden ............... San Diego Chargers Roger Brown .............. New England Patriots New England Patriots Ken Barefoot ..........................Detroit Lions New York Giants Washington Redskins Green Bay Packers Carroll Dale .................... Minnesota Vikings Green Bay Packers Chad Beasley ................. Carolina Panthers Phil Bryant ...................Philadelphia Eagles Los Angeles Rams Cleveland Browns Buffalo Bills Kansas City Chiefs André Davis ......................... Buffalo Bills Tom Beasley ................Washington -

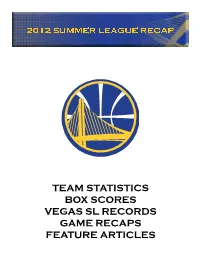

Team Statistics Box Scores Vegas Sl Records Game

TEAM STATISTICS BOX SCORES VEGAS SL RECORDS GAME RECAPS FEATURE ARTICLES WARRIORS FINAL SUMMER LEAGUE ROSTER WARRIORS SUMMER LEAGUE RESULTS NO PLAYER POS HT WT DOB PRIOR TO NBA/FROM NBA EXP. DATE OPPONENT RESULT SCORE HIGH POINTS/REBOUNDS/ASSISTS OPPS HIGH POINTS/REBOUNDS/ASSISTS July 13 vs. LA Lakers W 90-50 Thompson 24/Green 9/Thompson 5 Goudelock 14/Majok 7/Morris 4 40 Harrison Barnes F 6-8 210 5/30/92 North Carolina/USA R July 14 vs. Denver W 95-74 Jenkins 24/Barnes & Ezeli 7/Thompson 4 Hamilton 18/Faried 8/Faried 3 July 18 vs. Miami W 65-62 Jenkins 17/Barnes 7/Three Players 2 Cole 15/Viney 8/Cole 4 20 Kent Bazemore G/F 6-5 195 7/1/89 Old Dominion/USA R July 20 vs. Chicago W 66-57 Barnes 20/Green 11/Ragland 3 Teague & Thomas 12/Thomas 16/Four Players 2 25 Justin Burrell F 6-8 244 4/18/88 St. John’s/USA R July 21 vs. New Orleans W 80-72 Jenkins 15/Three Players 6/Jenkins 4 Henry 21/Thomas 8/Roberts 5 31 Festus Ezeli C 6-11 255 10/21/89 Vanderbilt/Nigeria R 23 Draymond Green F 6-7 230 3/4/90 Michigan State/USA R WARRIORS SUMMER LEAGUE STATS 22 Charles Jenkins G 6-3 220 2/28/89 Hofstra/USA 1 PLAYER G GS MIN FGM FGA PCT 3FGM 3FGA PCT FTM FTA PCT OFF DEF TOT AST PF DQ STL TO BLK PTS AVG Klay Thompson 2 2 59 14 27 .519 10 14 .714 3 4 .750 2 10 12 9 5 0 3 9 3 41 20.5 52 Dallas Lauderdale F 6-8 260 9/11/88 Ohio State/USA R Harrison Barnes 5 5 168 30 76 .395 8 14 .571 16 22 .727 10 18 28 2 11 0 9 7 0 84 16.8 21 Joe Ragland G 6-0 185 11/11/89 Wichita State/USA R Charles Jenkins 5 5 139 22 43 .512 0 2 .000 27 28 .964 0 7 7 14 6 0 8 14 0 71 14.2 -

'13'A3&1! N' .U \Xn'

\xn‘. a.:1Lynn: ‘n ‘'‘13J3&1!‘.a ~.u . housemaéwith .. highsspesd; interns“! ”$181"- sable-133$“ *‘e¢h”'9"997 $6.00 Minimum Order 0 Before 5pm to Campus Oam— iOpm/7Days LARGE SUB Get an SMALL SUB * installation or FREE Shipment of Cable Ms em“ mm PLUS Yaw alarm is always an“ 6 menths tar $34.95 per month! Brovgmto you by: Not valid with any other offers. TlME WARNER One coupon perperson pervisit. f W " g '_ »~ _ CAVE LE ‘ . Expires 3.15.2003 15:34:; cu, - ., l 7 l. Now anything?possible ,8 arm-2:3 {am} 19' www.8ubConsciousSubs.com Employment Opportunities Available, Lunch and/or Dinner, Full or Part Time! Will work with your schedule - Drivers, Cashiers and Cooksl Sggngxloggfi;sggggygg ; 5% TOP 25 COMMENTARY BY MATT MIDDLETON 5% THE FAN 7 COMMENTARY BYANDREW CARTER % MIND GAMES JERRICHO COTCHERY HAS HIS SIGHTS ONTHE RECORD BOOK 3% SPEED DEMONS THEWOLFPACK’S FASTESTTEAM EVER? :32 GREAT EXPECTATIONS DRIVE A LITTLE 3g; Iflfi‘hmlféé‘xnews PRETENDERSAND CONTENDERS SAVE A LOT 3% SLIEESIEEIE’SE’SHEDULE XE HUNGRY LIKE THE WOLF WOLFPACK SUPER HEROES IN ACTION mmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmu KATIE KINSEY MATTMIDDLETON ANDREW B. CARTER TIM LYTIIINENKO JACJKSON BROWN MARK MCLAWHORN THUSHANAMARASIRIWARDENA CARIE WINDHAM ©2003 TECHNICIAN I ;y'-S_‘ir..i_a.:lxi-x 5”,; J‘J- fl'?“a‘a.=4u—“‘.;."r Wa—nx‘ aw: --.- .15.; .R‘ ,. 2'1"” . (a.-. my. .- ...- . _ . -' 1. Miami The only thing that stands in the way destroyed Maryland in its season finale to finish tied for of the real national champions of 2002~winning second andjust a game out of first. -

2 0 0 3 R E V Ie W

2003 REVIEW Kevin Jones earned consensus All-America honors last season in helping Virginia Tech to an 8-5 record and its 11th-straight bowl bid INAUGURAL SEASON IN THE ACC VirginiaCharting Tech’s theAll-Americans Hokies • Senior center Jake Grove Infi nity-Tbecame the BI most white honored stroke, fi ll 60 percent, no caps offensive lineman in school 2003 history when he received the Rimington Trophy as Start Chart the nation’s top center and earned unanimous All-America Pos. Offense (starts) recognition. Grove became FL Justin Hamilton (6) the third Tech player to Richard Johnson (3) receive unanimous All- Chris Shreve (4) America honors, joining Jim LT Jimmy Martin (13) Pyne, who was also a center, LG Will Montgomery (10) and defensive end Corey Jacob Gibson (3) Moore. Grove played over C Jake Grove (13) 700 snaps during the 2003 RG Jacob Gibson (7) season and graded out over James Miller (6) 91 percent for the Hokies’ 13 RT Jon Dunn (12) games. Jacob Gibson (1) TE Keith Willis (11) • Tech fi nished in a tie Jeff King (2) with Miami and North Carolina QB Bryan Randall (13) State for the Division I-A lead FB Doug Easlick (13) in scores by return during TB Kevin Jones (13) the regular season with 10. SE Ernest Wilford (13) The Hokies were the only one of the three schools to also DeAngelo Hall fi nished the season ranked fi fth in the NCAA in Pos. Defense (starts) score on a return during their punt return average and helped the Hokies tie for best in the E Nathaniel Adibi (11) bowl game, bringing their nation in scores by return with 10. -

Virginia Tech Football

VIRGINIA TECH FOOTBALL AMERICA’S LONGEST ACTIVE BOWL STREAK - 27 STRAIGHT • 11 CONFERENCE TITLES - 4 ACC TITLES • 910.0 SACKS, 401 INTS LEAD FBS SINCE 1996 • #HARDHATMENTALITY VIRGINIA TECH (4-3, 4-2) Nov. 14 • 12:00 PM • ESPN • Lane Stadium • Blacksburg, Va. #9 MIAMI (6-1, 5-1) Justin Fuente Manny Diaz Alma Mater: Murray State (1999) Alma Mater: Florida State (1995) Record at VT: 37-23 (5th Season) Record at Miami: 12-8 (2nd Season) Career Record: 63-46 (9th Season) Career Record: 12-8 (2nd season) GAME 8 Record vs. Opp: 1-0 Record vs. Opp: 0-1 VIRGINIA TECH HOSTS MIAMI GIVE ‘EM THE HOOK - QB HENDON HOOKER VICE SQUAD - TECH’S O-LINE POWERING OFFENSE • Tech returns to ACC play when No. 9 Miami visits • QB Hendon Hooker owns an 8-4 record as Tech’s starter. He has been • VT already has 21 rushing TDs after scoring 22 in 2019. That Blacksburg (11/14). responsible for 15 TDs (team-high 8 rushing/7 passing) in 2020. figure is tied for fourth in the nation behind Army (26), BYU (25) • VT is coming off a last-second 38-35 loss vs. No. 25 • Hooker’s 164 rushing yards vs. Boston College (10/17) were the most and Tulane (24). Clemson, UNC & ND also have 21 rush TDs. Liberty (11/7), while Miami got a 44-41 win at NC State by a Tech QB since Michael Vick had 210 at Boston College (9/30/00) • Tech leads all P5 squads in rushing (277.4 ypg.).