Appendix a Notice of Preparation and Responses to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinolecreeksedimentfinal

Pinole Creek Watershed Sediment Source Assessment January 2005 Prepared by the San Francisco Estuary Institute for USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service and Contra Costa Resource Conservation District San Francisco Estuary Institute The Regional Watershed Program was founded in 1998 to assist local and regional environmental management and the public to understand, characterize and manage environmental resources in the watersheds of the Bay Area. Our intent is to help develop a regional picture of watershed condition and downstream effects through a solid foundation of literature review and peer- review, and the application of a range of science methodologies, empirical data collection and interpretation in watersheds around the Bay Area. Over this time period, the Regional Watershed Program has worked with Bay Area local government bodies, universities, government research organizations, Resource Conservation Districts (RCDs) and local community and environmental groups in the Counties of Marin, Sonoma, Napa, Solano, Contra Costa, Alameda, Santa Clara, San Mateo, and San Francisco. We have also fulfilled technical advisory roles for groups doing similar work outside the Bay Area. This report should be referenced as: Pearce, S., McKee, L., and Shonkoff, S., 2005. Pinole Creek Watershed Sediment Source Assessment. A technical report of the Regional Watershed Program, San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI), Oakland, California. SFEI Contribution no. 316, 102 pp. ii San Francisco Estuary Institute ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors gratefully -

Contra Costa County

Historical Distribution and Current Status of Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California Robert A. Leidy, Environmental Protection Agency, San Francisco, CA Gordon S. Becker, Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA Brett N. Harvey, John Muir Institute of the Environment, University of California, Davis, CA This report should be cited as: Leidy, R.A., G.S. Becker, B.N. Harvey. 2005. Historical distribution and current status of steelhead/rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration CONTRA COSTA COUNTY Marsh Creek Watershed Marsh Creek flows approximately 30 miles from the eastern slopes of Mt. Diablo to Suisun Bay in the northern San Francisco Estuary. Its watershed consists of about 100 square miles. The headwaters of Marsh Creek consist of numerous small, intermittent and perennial tributaries within the Black Hills. The creek drains to the northwest before abruptly turning east near Marsh Creek Springs. From Marsh Creek Springs, Marsh Creek flows in an easterly direction entering Marsh Creek Reservoir, constructed in the 1960s. The creek is largely channelized in the lower watershed, and includes a drop structure near the city of Brentwood that appears to be a complete passage barrier. Marsh Creek enters the Big Break area of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta northeast of the city of Oakley. Marsh Creek No salmonids were observed by DFG during an April 1942 visual survey of Marsh Creek at two locations: 0.25 miles upstream from the mouth in a tidal reach, and in close proximity to a bridge four miles east of Byron (Curtis 1942). -

(Oncorhynchus Mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California

Historical Distribution and Current Status of Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California Robert A. Leidy, Environmental Protection Agency, San Francisco, CA Gordon S. Becker, Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA Brett N. Harvey, John Muir Institute of the Environment, University of California, Davis, CA This report should be cited as: Leidy, R.A., G.S. Becker, B.N. Harvey. 2005. Historical distribution and current status of steelhead/rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward p. 3 Introduction p. 5 Methods p. 7 Determining Historical Distribution and Current Status; Information Presented in the Report; Table Headings and Terms Defined; Mapping Methods Contra Costa County p. 13 Marsh Creek Watershed; Mt. Diablo Creek Watershed; Walnut Creek Watershed; Rodeo Creek Watershed; Refugio Creek Watershed; Pinole Creek Watershed; Garrity Creek Watershed; San Pablo Creek Watershed; Wildcat Creek Watershed; Cerrito Creek Watershed Contra Costa County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 39 Alameda County p. 45 Codornices Creek Watershed; Strawberry Creek Watershed; Temescal Creek Watershed; Glen Echo Creek Watershed; Sausal Creek Watershed; Peralta Creek Watershed; Lion Creek Watershed; Arroyo Viejo Watershed; San Leandro Creek Watershed; San Lorenzo Creek Watershed; Alameda Creek Watershed; Laguna Creek (Arroyo de la Laguna) Watershed Alameda County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 91 Santa Clara County p. 97 Coyote Creek Watershed; Guadalupe River Watershed; San Tomas Aquino Creek/Saratoga Creek Watershed; Calabazas Creek Watershed; Stevens Creek Watershed; Permanente Creek Watershed; Adobe Creek Watershed; Matadero Creek/Barron Creek Watershed Santa Clara County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. -

Examples of Projects Anticipated to Be Eligible for Restoration Authority Grants

Examples of projects anticipated to be eligible for Restoration Authority grants. PROJECT COUNTY PROJECT DESCRIPTION LEAD ORGANIZATIONS Peninsula and South Bay Completion of restoration and park improvements (entry, parking, Candlestick Point - San California State Parks signs, and trails), monitoring of restored wetlands, and operation and Yosemite Slough Francisco Foundation maintenance of wetlands and visitor amenities San Design and construction of a new soft shoreline to create habitat, China Basin Port of San Francisco Francisco improve public access, and protect the park from sea level rise. Environmental education programs for students of all ages at the Golden Gate National Crissy Field Center. The Center offers place-based exploration that focuses Crissy Field Educational San Parks Conservancy, on the interaction between humans and nature and makes use of the Programs Francisco National Park Service, natural and cultural resources of the restored Crissy Field wetland and the Presidio Trust Tennessee Hollow watershed. Design and construction of a living, natural shoreline to protect Heron’s Head park from erosion and sea level rise, create habitat San enhancements and protect public access; expansion of the Port’s existing Heron’s Head Park Port of San Francisco Francisco habitat education and outreach program for K-12 graders on Bay habitat and natural history; and removal of a creosote-pile pier in the waters to the north side of Heron’s Head Park, to improve wildlife habitat. San Design and construction of shoreline improvements to support habitat Islais Creek Port of San Francisco Francisco creation, protect against erosion and remove creosote piles. Design and construction of a new 4-acre shoreline and park area, San Pier 70 - Slipways Park including natural habitat areas, living shoreline, wetlands, and public access Port of San Francisco Francisco areas. -

Pinole GPU Draft Cover 2010.Ai

CHAPTER 10: NATURAL RESOURCES AND OPEN SPACE CHAPTER 10 NATURAL RESOURCES AND OPEN SPACE TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 10.0-1 Purpose ......................................................................................................................... 10.0-1 Relationship to Other General Plan Elements ............................................................... 10.0-2 Issues and Considerations .................................................................................................. 10.0-2 Natural Resources Setting............................................................................................. 10.0-3 Plant and Animal Habitat ............................................................................................... 10.0-3 Open Space Setting ...................................................................................................... 10.0-7 Visual Resources ........................................................................................................ 10.0-13 Goals, Policies, and Implementation Actions ..................................................................... 10.0-14 Goals .......................................................................................................................... 10.0-14 Policies and Implementation Actions ........................................................................... 10.0-14 TABLES Table 10.1 Existing Habitats -

Community Facilities and Infrastructure

6 Community Facilities and Infrastructure 4 4 TENNENTTENNENT AVE AVE SYCAM SYCOARMO E ARVEE AVE MapMap 6.1 6.1 VE R AVE EF R Community Facilities LO A UGEF Community Facilities ABLO IO UG P B V IO NPA A SAN LL VA SA EY LL R EY D R HERCULESHERCULES D COUNTYk APPIAN WY R e efu COUNTYk e gio r APPIAN WY R San Pablo Bay Ce Cefre y e ueg Owned and operated by City of Richmond San Pablo Bay it r kio C r C I-80 re r y e Owned and operated by City of Richmond iat k r I-80 P r G a I N G P O I N L O E Y L Libraries V W E A K PINOLE Y Libraries L V W P L A K E PINOLE D LY P N L RED D O Y M NH RD Community Centers Parchester IOC RM H R P Community Centers Community Center in C D Parchester I o R le RE P Community Center iCn D M re oe U le E k L COUNTY C M r B ee U COUNTY k ALH L AMB Owned and operated by partner agencies B R R R ILLTOP D A V heem Cr H ALH A eek Murphy AMB LL R RAEY Owned and operated by partner agencies R HILLTOP D Elementary V R heem Cr Highland A D eek Murphy LL Contra Costa Elementary School EY GIANT RD APPIAN WY Elementary Valley View R Community HighlandSchool D Schools Contra CostaCollege Elementary School Elementary School GIANT RD APPIAN WY Valley View Community School ElementaryMay Valley CommunitySchool Center Schools Creek College San Pablo De Anza High andMay Valley Community Center RUMRILL BLVD Sheldon Colleges ablo Creek Delta Continuation School San P Elementary COUNTY COUNTY AM RD De Anza High and BR O D School Colleges RUMRILLO BLVD RD 20 DR PABL Sheldon OKSID EL PORTAL SAN Delta Continuation School ANCH RD E DR -

Carquinez Strait Regional Shoreline

Carquinez Strait Regional Shoreline Resource Analysis East Bay Regional Park District CARQUINEZ STRAIT REGIONAL SHORELINE RESOURCE ANALYSIS Adopted: November 17, 1992 Resolution No: 1992-11-302 Prepared by: East Bay Regional Park District Planning/ Stewardship Department 2950 Peralta Oaks Drive Oakland, CA 94605 " .. .1 was almost wild to get out alone with the big sail and go tearing down the Carquinez Strait ... " Jack London, Tales of the Fish Patrol FOREWORD Carquinez Strait channels waters flowing from Sierran snow beds through the vast fields of the Central Valley to meet the salt waters of the Pacific Ocean in the San Fran cisco Bay. The broad streams of the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers converge in the Carquinez Strait and along their course supply water for over two thirds of California residents. Much of this immense ancient water system is visible from the bluffs rising above the Carquinez Strait Regional Shoreline. We usually speed by these waters on freeways or over them on bridges, catching a glimpse of sailboats on the way to somewhere else. At Carquinez Strait Regional Shoreline one can sit quietly under coastal bluffs next to the water's edge and contrast the relatively recent trappi1\gs of human history, the factories, subdivisions, railroads and ships, to the larger, more permanent forces of nature at this northern border of the Bay. This waterfront area offers tremendous potential for recreation, preservation of natural resources and education. The diversity of resources is reflected in the special aspects of the park's location; its views, open water, trail system, marine climate and historic buildings. -

San Francisco Bay Area Endangered Species at Risk from Pesticides

Poisoning Our Imperiled Wildlife San Francisco Bay Area Endangered Species at Risk from Pesticides A Center for Biological Diversity Report February 2006 Writing: Jeff Miller Editing: Julie Miller Photo Editing & Design: T. DeLene Beeland Maps: Curtis Bradley CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY BECAUSE LIFE IS GOOD 1095 Market Street Suite 511 San Francisco CA 94103 415.436.9682 www.biologicaldiversity.org Table of Contents Executive Summary........................................................................................................ 3 Background on Pesticide Impacts.................................................................................. 5 Contaminated Waterways................................................................................... 5 Contaminated Sediments................................................................................... 5 Pesticide Drift...................................................................................................... 6 Effects of Pesticides on Wildlife.......................................................................... 6 Birds........................................................................................................ 6 Amphibians............................................................................................. 7 Fishes..................................................................................................... 7 Insects..................................................................................................... 7 Plants..................................................................................................... -

Pinole Creek Fish Passage Improvement Project to Eliminate a Barrier to Migration of Anadromous Steelhead

COASTAL CONSERVANCY Staff Recommendation March 26, 2015 PINOLE CREEK FISH-PASSAGE IMPROVEMENT PROJECT Project No. 14-005-01 Project Manager: Melanie Denninger RECOMMENDED ACTION: Authorization to disburse up to $165,000 to the Contra Costa County Resource Conservation District for construction of fish-passage improvements on Pinole Creek under and adjacent to Interstate 80 in the City of Pinole. LOCATION: City of Pinole in Contra Costa County (Exhibits 1 and 2) PROGRAM CATEGORY: San Francisco Bay Area Conservancy Program EXHIBITS Exhibit 1: Project Regional Location Exhibit 2: Project Vicinity Exhibit 3: CEQA Documents Exhibit 4: Project Photos Exhibit 5: Project Design Exhibit 6: Project Letters RESOLUTION AND FINDINGS: Staff recommends that the State Coastal Conservancy adopt the following resolution pursuant to Sections 31160 et seq. of the Public Resources Code: “The State Coastal Conservancy hereby authorizes the disbursement of an amount not to exceed $165,000 (one hundred sixty-five thousand dollars) to the Contra Costa Resource Conservation District (“the District”) for the Pinole Creek Fish Passage Improvement Project to eliminate a barrier to migration of anadromous steelhead. This authorization is subject to the following conditions: 1. Prior to the disbursement of any Conservancy funds, the District shall submit the following for review and approval of the Executive Officer of the Conservancy: A. A detailed work program, project budget, and schedule; B. Evidence that all permits and approvals necessary for the project have been obtained; Page 1 of 8 PINOLE CREEK FISH-PASSAGE IMPROVEMENT PROJECT C. A plan for the installation of a sign acknowledging Conservancy funding; and D. The name(s) and qualifications of any contractors that the District intends to employ for the project. -

2017 Map Web Download Pinole Watershed

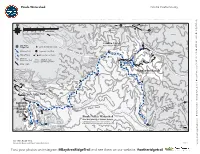

Pinole Watershed Contra Costa County n Canyon kli Rd an Fr BNSF RR PRIVATE To Martinez 4 N eastbound To Martinez 0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1.0 mile PRIVATE Franklin Canyon Golf Course C turn off 4 before 0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1.0 kilometer h r railroad bridge i s t Contour interval 200 feet i PRIVATE To Hercules e R GAP d . 200 on P B Franklin Cany N S Bay Area Muir Heritage Land Trust F EBRPD Regional Trails R Ridge Trail ail B ro Re la ad fug l ck io i P Multiuse Trail Segment Start/End V Road* ra Trail h al T o le e y b O.1 Rd 0.6 . 0.7 e Hiking/Biking Miles between Points l Goat il 820' m No access 760' d l Multiuse in rai Gray W nak T Connector Trail EBMUD Trails ps e PRIVATE Name* (permit required*) hi 0.9 W 600 0.8 Other Trails dra Woo t T ra 400 il Ridge * ad Fernandez Ranch 600 o 1.3 dead end 600 R Muir Heritage Land Trust s 340' a Road* im S 0.7 To Pinole Pin 807' ole Creek 800 P V PRIVATE a 1069' lle D y o w Rd 800 n . Oak e Pinole Creek r 200 T Simas ra d il oa Pinole Valley Park R 1.0 400 l Moth l i 400 Bar-X m y 600 alle R 1.8 d V d n a i br . Creek m W a Creek lh GAP 400 Ridge 1 Sobrante S 0.3 A No. -

Genplan4.1 Circulation Element Maps

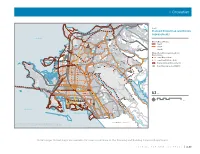

4 Circulation 4 TENNENT AVE SYCAMO RE AVE Map 4.1 VE R Planned Pedestrian and Bicycle A EF LO UG B IO PA N VA SA LL EY R Improvements HERCULES D COUNTYk APPIAN WY R e ef e ug r io San Pablo Bay C Cre ty e ri I-80 k r a G P I N O Existing Bicycle Routes L E Y W V A K PINOLE L Class I P L E D Y N R O D M Class II H C I R R P in D o le E C Class III M r ee U COUNTY k L B A LHAM R BR R ILLTOP D A V Planned Pedestrian Improvements and heem Cr H A eek V LL A EY L R Bicycle Routes L D E Y GIANT RD APPIAN WY V I E Class I Bicycle Route W R Creek D San Pablo Class II and III Bicycle Route RUMRILL BLVD COUNTY AM RD COUNTY B O D Bicycle and Pedestrian Connector RO RD 20 DR ABL OKSI EL PORTAL AN P ANCH RD DE DR S O R ASTR C Pedestrian Improvement District SAN PABLO COUNTY RICHMOND PKWY CONTRA COSTA COUNTY MCBRYDE AVE 13TH ST 23RD ST SOLANO AVE COUNTY Richmond BARRETT AVE MACDONALD AVE BART Station W ild cat Cr eek GARRARD BLVD BART - Richmond Line I-580 CARLSON BLVD San Pablo A 50 RL IN Reservoir El Cerrito Del Norte G T 10 ACRES WEST CUTTING BLVD HARBOUR WY BART Station O CUTTING BLVD N B L V D N POTRERO AVE EL CERRITO SAN PABLO AVE 0 0.5 1 2 MILES I-80 MOESER LN San Francisco Bay KENSINGTON Richmond Inner Harbor CENTRAL AVE El Cerrito Plaza FAIRMOUNT BARTAVE Station ALAMEDA COUNTY Source: City of Richmond, Contra Costa County, Metropolitan Transportation Commission, Thomas Bros. -

Vision Plan for the Refugio Creek Watershed

REFUGIO CREEK WATERSHED VISION PLAN CITY OF HERCULES, CALIFORNIA SEPTEMBER 2009 DRAFT Acknowledgements The Refugio Creek Watershed Vision Plan was produced through a collaborative process led by the City of Hercules and facilitated by Restoration Design Group. Common Sense California, the State Coastal Conservancy, and the City of Hercules funded the project. The City of Hercules would like to thank the guest speakers who contributed their time and provided their knowledge to the planning process. Speakers included: Roger Leventhal, FarWest Engineering Erik Stromberg, Restoration Design Group Jim Hale, Contra Costa Fish and Wildlife Committee Juliana Gonzalez, The Watershed Project Phillip Bachand, Bachand & Associates The City of Hercules would also like to thank everyone who volunteered their time and thoughts to participate in the planning process and craft the Refugio Creek Watershed Vision Plan. The Vision Plan document was prepared for the city of Hercules by the Restoration Design Group. Restoration Design Group, LLC 2612b Eighth Street RDG Berkeley, CA 94710 T 510.644.2798 F 510.644.2799 www.restorationdesigngroup.com ii SEPTEMBER 2009 Envision a watershed... “The Refugio Creek Watershed Vision Planning Group envisions a watershed with healthy creeks and ponds that provide habitat for wildlife, trails that unify and celebrate the watershed; and communities that care for, learn about, and understand the watershed.” iii REFUGIO CREEK WATERSHED VISION PLAN Contents 1 Introduction 1 Watershed Vision Plan 1 Public Process 3 Background Information 3 The Watershed 4 Watershed History 5 Current Land Use 8 Connections 9 Habitat Types 13 Watershed Tour 15 The Vision 15 Overview 15 Access 19 Education and Outreach 23 Creeks 24 Ponds 25 Wildlife and Nature 25 Storm Water and Water Quality 28 Next Steps 28 Community Organizing 28 Trail Planning 28 Additional Study 28 Conclusion 29 References The Refugio Creek Watershed is located in Western Contra Costa County and drains into San Pablo Bay.