Title of Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garden City Gladstone Gordonville Halfway Hannibal Harrisonville

Garden City Harrisonville Jackson KFME-F 80s Hits KCFX Classic Rock KUGT Contemporary Christian / Religious Teaching 105.1 100000W 859ft 101.1 97300w 993ft 1170 250 ND-D +Radio 2000 +Susquehanna Radio Corp. The Light & Power Co., Inc. Managed by: Susquehanna Radio Corp. Sister to: KCMO, KCMO-F 573-243-3100 fax: 573-243-0640 913-514-3000 fax:913-514-3003 913-514-3000 fax:913-514-3001 PO Box 546, 63755,1301 Woodland Dr, 63755 5800 Foxridge Dr Fl 6, Mission KS 66202 5800 Foxridge Dr Fl 6, Mission KS 66202 GM Jane Sandvos PD Wayne Elfrink GM/PD Dave Alexander SM Janel Thiessen GM Pam Malcy SM Steve Sobek CE Palmer Johnson CE Dennis Eversoll PD Don Daniels CE Dennis Eversoll www.e1051.fm www.thefoxrocks.com Kansas City Arbitron 3.2 Shr 7000 AQH Kansas City Arbitron 3.4 Shr 7400 AQH Jefferson City KWOS Talk I News Gladstone High Point 950 5000/500 DA-N +Zimmer Broadcasting Co., Inc. KGGN Black Gospel KMCV Religious Teaching* Sister to: KATI, KCLR-F, KCMQ, KFAL, KKCA, 890 960 DA-D 89.9 18000w 325ft KSSZ, KTGR, KTXY +Mortenson Broadcasting Co. +Bott Broadcasting Co. 573-893-5696 fax:573-893-4137 816-333-0092 fax:816-363-8120 913-642-7770 3109 S 10 Mile Dr, 65109 1734 E 63rd St Ste 600, Kansas City 64110 10550 Barkley St, Overland Park KS 66212 GM Ron Covert SM Stew Steinmetz GM Doris Newman PD Reggie Brown GM Rich Bott SM Trina Phelps PD John Marsh CE Steve Morse Kansas City Arbitron 0.6 Shr 1200 AQH Jefferson City Market www.kwos.com Jefferson City Market Gordonville Hollister KLIK Talk 1240 1000/1000 ND KCGQ-F Rock KBCV cp-new +Premler Marketing Group 99.3 5000w 358ft 1570 5000/3000 DA-2 Sister to: KJMO, KLIK-F, KOQL, KPLA +Zimmer Broadcasting Co., Inc. -

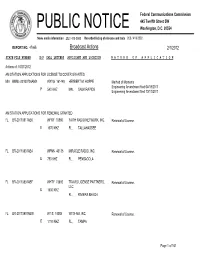

Broadcast Actions 2/1/2012

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 47665 Broadcast Actions 2/1/2012 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 01/27/2012 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR LICENSE TO COVER GRANTED MN BMML-20100726AMX WXYG 161448 HERBERT M. HOPPE Method of Moments Engineering Amendment filed 04/19/2011 P 540 KHZ MN , SAUK RAPIDS Engineering Amendment filed 10/17/2011 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED FL BR-20110817ABK WFRF 70860 FAITH RADIO NETWORK, INC. Renewal of License. E 1070 KHZ FL , TALLAHASSEE FL BR-20110831ABA WPNN 43135 MIRACLE RADIO, INC. Renewal of License. E 790 KHZ FL , PENSACOLA FL BR-20110831ABF WHTY 73892 TRAVIS LICENSE PARTNERS, Renewal of License. LLC E 1600 KHZ FL , RIVIERA BEACH FL BR-20110901ABW WTIS 74088 WTIS-AM, INC. Renewal of License. E 1110 KHZ FL , TAMPA Page 1 of 161 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 47665 Broadcast Actions 2/1/2012 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 01/27/2012 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED FL BR-20110906AFA WEBY 64 SPINNAKER LICENSE Renewal of License. -

Missouri 2007Annrpt.Pdf

Missouri Department of Transportation Highway Safety Division P.0. Box 270 Jefferson City, MO 65702 573-757-4767 or 800-800-2358 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword Executive Summary Program Areas (~lprogramsl are hom the Regular 402 Grant Program unless otherwise specified.) I. Police Traffic Services (including Aggressive Driving, Speed Involvement, and Older Drivers) 11. Alcohol (including Youth Alcohol, 410, 154 AL funds) 111. Occupant Protection (seat belt use, child safety seat use, motorcycles and school buses, 20 1072003(b),20 11 (d), 1906, and 154 HE funds) IV. Engineering and Data Collection (402 and 408 funds) V. Public Information and Education FY 2007 Budget and Project Listing FOREWORD The MoDOT mission is to provide a world-class transportation experience that delights our customers and promotes a prosperous Missouri. The Highway Safety Division (HSD) works specifically to reduce the number and severity of traffic crashes resulting in deaths and injuries. This requires the staff of the Highway Safety Division to work closely with state and local agencies in an attempt to develop programs which are innovative, cost efficient and, above all, effective in saving lives. This is accomplished through development and administration of the Governor's Highway Safety Program. In keeping with this administration's philosophy to provide quality customer service, we strive to incorporate involvement from both traditional and non-traditional partners in our safety endeavors. Expanded partnerships enable us to reach a broader base of customers with the life-saving messages of traffic safety. The accomplishments noted in this report would not have occurred without the dedication and foresight of the staff of the Highway Safety Division and the support of the Missouri Department of Transportation. -

2016 ANNUAL EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT Mississippi River Radio LLC Cape Girardeau Employment Unit

2016 ANNUAL EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT Mississippi River Radio LLC Cape Girardeau Employment Unit Stations: KEZS-FM, Cape Girardeau, MO KZIM(AM), Cape Girardeau, MO KGIR(AM), Cape Girardeau, MO KCGQ-FM, Gordonville, MO KGKS(FM), Scott City, MO KLSC(FM), Malden, MO KMAL(AM), Malden, MO KSIM(AM), Sikeston, MO Reporting Period: 09/21/2015 – 09/20/2016 No. of Full-time Employees: More than 10 Small Market Exemption: Yes During the Reporting Period, a total of 9 full time positions were filled. The information required by FCC Rule 73.2080(c)(6) is provided in the charts that follow. INITIATIVES The employment unit engaged in the following broad outreach initiatives in accordance with various elements of FCC Rule 73.2080(c)(2): Participated in job fairs by station personnel who have substantial responsibility in making hiring decisions. Date of Station Participation: October 8, 2015 Participating Employees: Station Air Personalities Host/Sponsor of Activity: SEMO University, Cape Girardeau, MO, Fall Career and Internship Fair Set up a booth display with handout guides of station formats, along with staff business cards and job applications. As interested students stopped by, they were educated on job opportunities, possible internships, and our stations. Date of Station participation: January 15, 2016 Participating Employees: Station Air Personalities Host/Sponsor of Activity: Jackson Middle School Career Fair Two sessions where students were introduced to radio as a career, information about our stations, questions asked and answered. Date of Station Participation: February 25, 2016 Participating Employees: Station Air Personalities Host/Sponsor of Activity: SEMO University, Cape Girardeau, MO, Spring Career and Internship Fair Attended and met with students with an interest in radio broadcasting. -

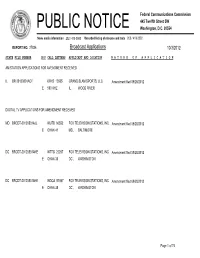

Broadcast Applications 10/3/2012

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 27836 Broadcast Applications 10/3/2012 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT RECEIVED IL BR-20120801ACF KFNS 13505 GRAND SLAM SPORTS, LLC Amendment filed 09/28/2012 E 590 KHZ IL , WOOD RIVER DIGITAL TV APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT RECEIVED MD BRCDT-20120531AJL WUTB 60552 FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, INC. Amendment filed 09/28/2012 E CHAN-41 MD , BALTIMORE DC BRCDT-20120531AKE WTTG 22207 FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, INC. Amendment filed 09/28/2012 E CHAN-36 DC , WASHINGTON DC BRCDT-20120531AKK WDCA 51567 FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, INC. Amendment filed 09/28/2012 E CHAN-35 DC , WASHINGTON Page 1 of 74 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 27836 Broadcast Applications 10/3/2012 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N LOW POWER FM APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING TX BALL-20121001AIB KERC-LP KERMIT RADIO ACADEMY, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License 135149 E TX , KERMIT From: KERMIT RADIO ACADEMY 93.7 MHZ To: HOLY SPIRIT OIL FILLED MINISTRY Form 314 FM AUXILIARY TRANSMITTING ANTENNA APPLICATIONS FOR AUXILIARY PERMIT ACCEPTED FOR FILING ND BXPH-20120928APK WDAY-FM 22123 RADIO FARGO-MOORHEAD, INC. -

2009–2010 College Catalog Your Reach

Three Rivers Community College: 2009–2010 Putting a better life within your reach. College Catalog Save Money Convenience · Why pay university prices? · Convenient classes on campus or at our TRCC offers the same freshman and Centers in Sikeston, Kennett, Malden, sophomore classes as four-year Portageville and Campbell. universities for about half the cost. · Choose day or evening classes. Start · Classes close to home reduce · Online classes offer flexibility. transportation costs. Focus on you Financial Aid · Anyone with a high school Here! · Pell Grants go further because diploma or GED can enroll. of our low tuition. · Courses geared for your success. · Use A+ funds to pay for classes. · Small classes and personalized · Help applying for grants attention. and scholarships. · Services such as tutoring, computer labs and Quality Education on-campus day care. · College courses that transfer everywhere. · Career programs for jobs that are in demand. • Course offerings and descriptions • Degree and Certificate Programs • College policies, procedures and Start information 2080 Three Rivers Blvd. • Poplar Bluff, MO 63901 1-877-TRY-TRCC1-877-TRY-TRCC •• www.trcc.eduwww.trcc.edu Now! from the President… Take the challenge: Enroll at Three Rivers ooking forward to my first residents age 25 and older, year as president of Three approximately 167,500 people, LRivers Community College, have never attended college. I have been thinking about chal- For those area residents ready to lenges. take on the President’s challenge In accepting this job, I accepted of going to college, Three Rivers is the challenges that come with lead- here to put higher education, and ing this college into an exciting the better life it brings, within your future, one I envision to include reach. -

Writer's Address Book Volume 4 Radio & TV Stations

Gordon Kirkland’s Writer’s Address Book Volume 4 Radio & TV Stations The Writer’s Address Book Volume 4 – Radio & TV Stations By Gordon Kirkland ©2006 Also By Gordon Kirkland Books Justice Is Blind – And Her Dog Just Peed In My Cornflakes Never Stand Behind A Loaded Horse When My Mind Wanders It Brings Back Souvenirs The Writer’s Address Book Volume 1 – Newspapers The Writer’s Address Book Volume 2 – Bookstores The Writer’s Address Book Volume 3 – Radio Talk Shows CD’s I’m Big For My Age Never Stand Behind A Loaded Horse… Live! The Writer’s Address Book Volume 4 – Radio & TV Stations Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................... 9 US Radio Stations ............................................................................................................ 11 Alabama .........................................................................................................................11 Alaska............................................................................................................................. 18 Arizona ........................................................................................................................... 21 Arkansas......................................................................................................................... 24 California ........................................................................................................................ 31 Colorado ........................................................................................................................ -

2017 ANNUAL EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT Mississippi River Radio LLC Cape Girardeau Employment Unit

2017 ANNUAL EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT Mississippi River Radio LLC Cape Girardeau Employment Unit Stations: KEZS-FM, Cape Girardeau, MO KZIM(AM), Cape Girardeau, MO KGIR(AM), Cape Girardeau, MO KCGQ-FM, Gordonville, MO KGKS(FM), Scott City, MO KLSC(FM), Malden, MO KMAL(AM), Malden, MO KSIM(AM), Sikeston, MO Reporting Period: 09/21/2016 – 09/20/2017 No. of Full-time Employees: More than 10 Small Market Exemption: Yes During the Reporting Period, a total of 6 full time positions were filled. The information required by FCC Rule 73.2080(c)(6) is provided in the charts that follow. INITIATIVES The employment unit engaged in the following broad outreach initiatives in accordance with various elements of FCC Rule 73.2080(c)(2): Participated in at least 4 job fairs by station personnel who have substantial responsibility in making hiring decisions. Date of Station Participation: September 29, 2016 Participating Employees: On Air Personality Host/Sponsor of Activities: Lincoln University Extension Career Day Event for students from selected Southeast Missouri schools. Presented descriptions of jobs available in field of radio. Was also a guest speaker Date of Station Participation: October 13, 2016 Participating Employees: Promotion Director Host/Sponsor of Activity: Southeast MO State University Fall Career Expo Set up booth display with handouts of station media kits, along with job applications. Interested students were educated on job opportunities, current openings, and questions were answered. Date of Station Participation: January 16, 2017 Participating Employees: Promotions Director Host/Sponsor of Activity: Jackson Junior High Career Fair Two sessions. Students were introduced to radio as a career, provided information about our stations, answered questions. -

Newspaper Organizations

CHAPTER 9 MISSOURI INFORMATION Cotton Harvest Photo courtesy of Missouri State Archives Publications Collection 864 OFFICIAL MANUAL Newspaper Organizations 802 Locust St., Columbia 65201 Telephone: (573) 449-4167 / FAX: (573) 874-5894 www.mopress.com The Missouri Press Association is an organiza- MARK MAASSEN tion of newspapers in the state. Executive Director Missouri Press Association Organized May 17, 1867, as the Editors and Publishers Association of Missouri, the name line County Herald newspaper office in historic was changed in 1877 to the Missouri Press As- Arrow Rock and maintains a newspaper equip- sociation (MPA). In 1922, the association became ment museum, which underwent renovations in a nonprofit corporation, and a central office was 2016, in connection with it. opened under a field manager whose job it was to travel the state and help newspapers with The Missouri Press Foundation administers problems. and funds seminars and workshops for newspa- per people, supports Newspapers In Education The association, located in Columbia, became programs, and funds scholarships and internships the fifth press association in the nation to finance for Missouri students studying community jour- its headquarters through member contributions. nalism in college. The MPA’s building was purchased in 1969. Membership in the association is voluntary. All As a founder of institutions, the Missouri daily newspapers in the state are members and 99 Press Association aided in the establishment of percent of the weekly newspapers are members. In the Confederate Soldiers’ Home, the upbuild- 2017, there were 236 weekly and daily newspa- ing of the normal schools, support of the public per members. -

Ch-Ch-Ch Changes!!!

The Magazine for TV and FM DXers July 2020 The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association Ch-Ch-Ch Changes!!! What? Again? THE VHF-UHF DIGEST THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, KEITH McGINNIS, JIM THOMAS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org/info Webmaster: Tim McVey Forum Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, John Zondlo and Mike Bugaj Your WTFDA Booard of Directors Doug Smith Mike Bugaj Keith McGinnis Jim Thomas [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Renewals by mail: Send to WTFDA, P.O. Box 501, Somersville, CT 06072. Check or MO for $10 payable to WTFDA. Renewals by Paypal: Send your dues ($10USD) from the Paypal website to [email protected] or go to https://www.paypal.me/WTFDA and type 10.00 or 20.00 for two years in the box. Our WTFDA.org website webmaster is Tim McVey, [email protected]. Our WTFDA Forums webmaster is Chris Cervantez, [email protected]. Fred Nordquist is in charge of club statistics at [email protected] Our email reflector is on Googlegroups. To join, send an email to [email protected] Visit our club website at http://www.wtfda.org . -

Florida Media Outlets

Florida Media Outlets Newswire’s Media Database provides targeted media outreach opportunities to key trade journals, publications, and outlets. The following records are related to traditional media from radio, print and television based on the information provided by the media. Note: The listings may be subject to change based on the latest data. ________________________________________________________________________________ Radio Stations 23. The Tom O'Brien Show 24. Val & Scott In The Morning 1. AM 1060 WMEL 25. W237CP-FM 2. AM Tampa Bay 26. W265CF-FM 3. Christian Connections with 27. WAFZ-AM Anthony Daughtery 28. WAFZ-FM [La Ley 92.1 FM] 4. Down The Rabbit Hole 29. WAIL-FM [WAIL 995] 5. DWAV-FM [WAVE 891] 30. WAMT-AM [NewsRadio AM 1190 6. Evening Edition with Ezra Marcus WAMT] 7. Home & Garden Radio 31. WAPE-FM [95.1 WAPE] 8. iHeartMedia, Inc. 32. WAPI-AM [1070 WAPI] 9. Into Tomorrow with Dave 33. WAPN-FM Graveline 34. WAVS-AM [Heartbeat Of The 10. Key Life Caribbean] 11. KKNW-AM 35. WAYR-AM [WAY Radio] 12. Living Sexy 36. WBHQ-FM [Beach 92.7] 13. Poydras Review 37. WBOB-AM [AM 600 & FM 100.3 14. Sirius XM NASCAR Radio The Answer] 15. SiriusXM Fantasy Sports Radio 38. WBVM-FM [Spirit FM 90.5] 16. TALKINPETS with Jon Patch 39. WBZW-AM [1520 The Biz] 17. The Doctor is In 40.WCCF-AM [Newsradio 1580] 18. The Edward Woodson Show 41. WCJX-FM [The X] 19. The Golfer Girls w/Natalie Gulbis & 42. WCNK-FM [98.7 Conch Country] Debbie Doniger 43. WCRM-AM 20. -

Broadcast Market Research TV Households

Broadcast Market Research TVHouseholds Everyindustryneedsameasureofthesizeofitsmarketplaceandtheradioandtelevisionindustriesare noexceptions. TELEVISION - U.S. AmajorsourceofsuchmediamarketdataintheUnitedStatesisNielsenMediaResearch(NMR),and oneofthemeasurementsittakesannuallyisTVHouseholds(TVHH).Ahomewithoneoperable TV/monitorisaTVHH,andNielsenisabletoextrapolateits“NationalUniverseEstimates”fromCensus BureaupopulationdatacombinedwiththisexpressionofTVpenetration. WithUsfromDayOne Theadventofbroadcastadvertising,inJuly1941,wascoincidentalwiththedawnofcommercial television,andwithintenyearsmarketresearchinthenewmediumwasinfullswing. SincetheFederalCommunicationsCommission(FCC)allowedthosefirstTVads—forSunOil,Lever Bros.,Procter&GambleandtheBulovaWatchCompany—reliableaudiencemeasurementhasbeen necessaryformarketerstotargettheircampaigns.TheproliferationofdevicesforviewingTVcontent andthecontinualevolutionofconsumerbehaviorhavemadethetaskmoreimportant—andmore challenging—thanever. Nevertheless,whiletherealityof“TVEverywhere”hasundeniablycomplicatedtheworkofaudience measurement,theuseofonerudimentarygaugepersists—thenumberofhouseholdswithaset,TVHH. NielsenMediaResearch IntheUnitedStates,NielsenMediaResearch(NMR)istheauthoritativesourcefortelevisionaudience measurement(TAM).BestͲknownforitsratingssystem,whichhasdeterminedthefatesofmany televisionprograms,NMRalsotracksthenumberofhouseholdsinaDesignatedMarketArea(DMA) thatownaTV. PublishedannuallybeforethestartofthenewTVseasoninSeptember,theseUniverseEstimates, representingpotentialregionalaudiences,areusedbyadvertiserstoplaneffectivecampaigns.