130117212379165321 Tech6.4DE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

— 2016 T&FN Men's U.S. Rankings —

50K WALK — 2016 T&FN Men’s U.S. Rankings — 1. John Nunn 2. Nick Christie 100 METERS 1500 METERS 110 HURDLES 3. Steve Washburn 1. Justin Gatlin 1. Matthew Centrowitz 1. Devon Allen 4. Mike Mannozzi 2. Trayvon Bromell 2. Ben Blankenship 2. David Oliver 5. Matthew Forgues 3. Marvin Bracy 3. Robby Andrews 3. Ronnie Ash 6. Ian Whatley 4. Mike Rodgers 4. Leo Manzano 4. Jeff Porter HIGH JUMP 5. Tyson Gay 5. Colby Alexander 5. Aries Merritt 1. Erik Kynard 6. Ameer Webb 6. Johnny Gregorek 6. Jarret Eaton 2. Kyle Landon 7. Christian Coleman 7. Kyle Merber 7. Jason Richardson 3. Deante Kemper 8. Jarrion Lawson 8. Clayton Murphy 8. Aleec Harris 4. Bradley Adkins 9. Dentarius Locke 9. Craig Engels 9. Spencer Adams 5. Trey McRae 10. Isiah Young 10. Izaic Yorks 10. Adarius Washington 6. Ricky Robertson 200 METERS STEEPLE 400 HURDLES 7. Dakarai Hightower 1. LaShawn Merritt 1. Evan Jager 1. Kerron Clement 8. Trey Culver 2. Justin Gatlin 2. Hillary Bor 2. Michael Tinsley 9. Bryan McBride 3. Ameer Webb 3. Donn Cabral 3. Byron Robinson 10. Randall Cunningham 4. Noah Lyles 4. Andy Bayer 4. Johnny Dutch POLE VAULT 5. Michael Norman 5. Mason Ferlic 5. Ricky Babineaux 1. Sam Kendricks 6. Tyson Gay 6. Cory Leslie 6. Jeshua Anderson 2. Cale Simmons 7. Sean McLean 7. Stanley Kebenei 7. Bershawn Jackson 3. Logan Cunningham 8. Kendal Williams 8. Donnie Cowart 8. Quincy Downing 4. Mark Hollis 9. Jarrion Lawson 9. Dan Huling 9. Eric Futch 5. Jake Blankenship 10. -

Women's 5000M

2020 US Olympic Trials Statistics – Women’s 5000m by K Ken Nakamura Summary: All time performance list at the Olympic Trials Performance Performer Time Name Pos Venue Year 1 1 14:45.35 Regina Jacobs 1 Sacramento 2000 2 2 15:01. 02 Kara Goucher 1 Eugene 2008 3 3 15:02.02 Jen Rhines 2 Eugene 2008 4 4 15:02.81 Shalane Flanagan 3 Eugene 2008 5 5 15:05.01 Molly Huddle 1 Eugene 2016 6 6 15:06.14 Shelby Houlihan 2 Eugene 2016 7 7 15:07.41 Shayne Culpepper 1 Sacramento 2004 Margin of Victory Difference Winning time Name Venue Year Max 26.20 14:45.35 Regina Jacobs Sacramento 2000 Min 0.07 15:07.41 Shayne Culpepper Sacramento 2004 Best Marks for Places in the Olympic Trials Pos Time Name Venue Year 1 14:45.35 Regina Jacobs Sacramento 2000 2 15:02.02 Jen Rhines Eugene 2008 3 15:02.81 Shalane Flanagan Eugene 2008 4 15:13.74 Amy Rudolph Sacramento 2004 Last five Olympic Trials Year Gold Time Silver Time Bronze Time 2016 Molly Huddle 15:05.01 Shelby Houlihan 15:06.14 Kim Conley 15:10.62 2012 Julie Culley 15:13.77 Molly Huddle 15:14.40 Kim Conley 15:19.79 2008 Kara Goucher 15:01.02 Jen Rhines 15:02.02 Shalane Flanagan 15:02.81 2004 Shayne Culpepper 15:07.41 Marla Runyan 15:07.48 Shalane Flanagan 15:10.52 2000 Regina Jacobs 14:45.35 Deena Drossin 15:11.55 Elva Dryer 15:12.07 All time US List Performance Performer Time Name Pos Venue DMY 1 1 14:23.92 Shelby Houlihan 1 Portland 10 July 2020 2 2 14: 26.34 Karissa S chweizer 2 Portland 10 July 20 20 3 3 14:34.39 Shelby Houlihan 1 Heusden -Zolder 21 July 2018 4 4 14:38.92 Shannon Rowbury 5 Bruxelles 9 S ept -

Njured and His Father Calling for Said Cronin

TtBB Serving Westfield, Scotch Plains and Fanwood Friday, July 22, 2005 50 cents A new look and a new pastor for Westfield church after a long career road including stints as a the same aspects as being an educator — THE RECORD-PRESS teacher, coach, administrator and counselor. teaching, counseling, inspiring and adminis- Boyea graduated from Potsdam College in trating. WESTFIELD — In the midst of the excit- 1981 with a degree in sociology and psycholo- "Ministry to nie is about teaching in the ing yet somewhat hectic renovations now gy. He then received his master's in educa- best sense of the word," he says. "It is not just underway at the First Congregational tion and administration at East Stroudsburg about imparting information, but about lov- Church of Westfield, Mark Boyea has found a University in Pennsylvania, where he met his ing, guiding, consoling and encouraging those home as the church's new senior minister. wife of more than 20 years, Cindy Seeley in your care." Boyea is the 14th full-time pastor in the Boyea. The couple have two children, Ryan While working as a coach and administra- church's 12/5-year history. and Kelsey, and currently live in Scotch tor, Boyea became interested in the psycho- Sitting in an office surrounded by signs of Plains. logical aspects of human performance. He construction, including the repainting of the Boyea went on to a career in education and pursued his doctorate in psychology at the sanctuary, now windows, ceiling repair, new counseling, serving as a teacher, coach and University of Maryland and earned his Ph.D. -

Stanford Cross Country Course

STANFORD ATHLETICS A Tradition of Excellence 116 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship award winners, including 10 in 2007-08. 109 National Championships won by Stanford teams since 1926. 95 Stanford student-athletes who earned All-America status in 2007-08. 78 NCAA Championships won by Stanford teams since 1980. 48 Stanford-affiliated athletes and coaches who represented the United States and seven other countries in the Summer Olympics held in Beijing, including 12 current student-athletes. 32 Consecutive years Stanford teams have won at least one national championship. 31 Stanford teams that advanced to postseason play in 2007-08. 19 Different Stanford teams that have won at least one national championship. 18 Stanford teams that finished ranked in the Top 10 in their respective sports in 2007-08. 14 Consecutive U.S. Sports Academy Directors’ Cups. 14 Stanford student-athletes who earned Academic All-America recognition in 2007-08. 9 Stanford student-athletes who earned conference athlete of the year honors in 2007-08. 8 Regular season conference championships won by Stanford teams in 2007-08. 6 Pacific-10 Conference Scholar Athletes of the Year Awards in 2007-08. 5 Stanford teams that earned perfect scores of 1,000 in the NCAA’s Academic Progress Report Rate in 2007-08. 3 National Freshmen of the Year in 2007-08. 3 National Coach of the Year honors in 2007-08. 2 National Players of the Year in 2007-08. 2 National Championships won by Stanford teams in 2007-08 (women’s cross country, synchronized swimming). 1 Walter Byers Award Winner in 2007-08. -

Indoor Track and Field DIVISION I MEN’S

Indoor Track and Field DIVISION I MEN’S Highlights Florida claims top spot in men’s indoor track: At the end of the two-day gamut of ups and downs that is the Division I NCAA Indoor Track and Field National Champion- ships, Florida coach Mike Holloway had a hard time thinking of anything that went wrong for the Gators. “I don’t know,” Holloway said. “The worst thing that happened to me was that I had a stomachache for a couple of days.” There’s no doubt Holloway left the Randal Tyson Track Center feeling better on Saturday night. That’s because a near-fl awless performance by the top-ranked Gators re- sulted in the school’s fi rst indoor national championship. Florida had come close before, fi nishing second three times in Holloway’s seven previous years as head coach. “It’s been a long journey and I’m just so proud of my staff . I’m so proud of my athletes and everybody associated with the program,” Holloway said. “I’m almost at a loss for words; that’s how happy I am. “It’s just an amazing feeling, an absolutely amazing feeling.” Florida began the day with 20 points, four behind host Arkansas, but had loads of chances to score and didn’t waste time getting started. After No. 2 Oregon took the lead with 33 points behind a world-record performance in the heptathlon from Ashton Eaton and a solid showing in the mile, Florida picked up seven points in the 400-meter dash. -

SUMMARY 100 Metres Men - Preliminary Round First 2 in Each Heat (Q) and the Next 3 Fastest (Q) Advance to the 1St Round

Moscow (RUS) World Championships 10-18 August 2013 SUMMARY 100 Metres Men - Preliminary Round First 2 in each heat (Q) and the next 3 fastest (q) advance to the 1st Round RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE DATE VENUE World Record 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM 23 16 Aug 2009 Berlin Championships Record 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM 23 16 Aug 2009 Berlin World Leading 9.75 Tyson GAY USA 31 21 Jun 2013 Des Moines, IA 10 August 2013 RANK PLACE HEAT BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH RESULT WIND 1 1 3 847 Barakat Mubarak AL-HARTHI OMA 15 Jun 88 10.47 Q -0.5 m/s Баракат Мубарак Аль -Харти 15 июня 88 2 1 2 932 Aleksandr BREDNEV RUS 06 Jun 88 10.49 Q 0.3 m/s Александр Бреднев 06 июня 88 3 1 1 113Daniel BAILEY ANT 09 Sep 86 10.51 Q -0.4 m/s Даниэль Бэйли 09 сент . 86 3 2 2 237Innocent BOLOGO BUR 05 Sep 89 10.51 Q 0.3 m/s Инносент Болого 05 сент . 89 5 1 4 985 Calvin KANG LI LOONG SIN 16 Apr 90 10.52 Q PB -0.4 m/s Кэлвин Канг Ли Лонг 16 апр . 90 6 2 3 434 Ratu Banuve TABAKAUCORO FIJ 04 Sep 92 10.53 Q SB -0.5 m/s Рату Бануве Табакаукоро 04 сент . 92 7 3 3 296Idrissa ADAM CMR 28 Dec 84 10.56 q -0.5 m/s Идрисса A дам 28 дек . 84 8 2 1 509Holder DA SILVA GBS 12 Jan 88 10.59 Q -0.4 m/s Холдер да Силва 12 янв . -

Arkansas Men's Track & Field Media Guide, 2012

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Arkansas Men's Track and Field Athletics 2012 Arkansas Men's Track & Field Media Guide, 2012 University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Athletics Media Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/track-field-men Citation University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Athletics Media Relations. (2012). Arkansas Men's Track & Field Media Guide, 2012. Arkansas Men's Track and Field. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/track- field-men/4 This Periodical is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arkansas Men's Track and Field by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS 2011 SEC OUTDOOR CHAMPIONS Index 1-4 History and Records 49-84 Table of Contents 1 Razorback Olympians 50-51 Media Information 2 Cross Country Results and Records 52-54 Team Quick Facts 3 Indoor Results and Records 55-61 The Southeastern Conference 4 Outdoor Results and Records 62-70 Razorback All-Americans 71-75 2011 Review 5-10 Randal Tyson Track Center 76 2011 Indoor Notes 6-7 John McDonnell Field 77 2011 Outdoor Notes 8-9 Facility Records 78 2011 Top Times and Honors 10 John McDonnell 79 Two-Sport Student Athletes 80 2012 Preview 11-14 Razorback All-Time Lettermen 81-84 2012 Outlook 12-13 2012 Roster 14 The Razorbacks 15-40 Returners 16-35 Credits Newcomers 36-40 The 2012 University of Arkansas Razorback men’s track and fi eld media guide was designed by assistant The Staff 41-48 media relations director Zach Lawson with writting Chris Bucknam 42-43 assistance from Molly O’Mara and Chelcey Lowery. -

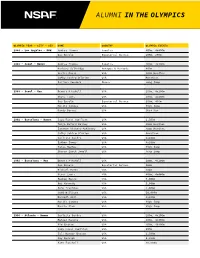

Alumni in the Olympics

ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS 1984 - Los Angeles - M&W Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m, 200m 1988 - Seoul - Women Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Barbara Selkridge Antigua & Barbuda 400m Leslie Maxie USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Juliana Yendork Ghana Long Jump 1988 - Seoul - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 200m, 400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Randy Barnes USA Shot Put 1992 - Barcelona - Women Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 1,500m Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeene Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Carlette Guidry USA 4x100m Esther Jones USA 4x100m Tanya Hughes USA High Jump Sharon Couch-Jewell USA Long Jump 1992 - Barcelona - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m Michael Bates USA 200m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Reuben Reina USA 5,000m Bob Kennedy USA 5,000m John Trautman USA 5,000m Todd Williams USA 10,000m Darnell Hall USA 4x400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Darrin Plab USA High Jump 1996 - Atlanta - Women Carlette Guidry USA 200m, 4x100m Maicel Malone USA 400m, 4x400m Kim Graham USA 400m, 4X400m Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 800m Juli Henner Benson USA 1,500m Amy Rudolph USA 5,000m Kate Fonshell USA 10,000m ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS Ann-Marie Letko USA Marathon Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeen Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Shana Williams -

NCAA Women: Duncan Powers LSU —

Volume 11, No. 42 June 12, 2012 version ii — NCAA Women: Duncan Powers LSU — by David Woods LSU scored 76 points to Oregon’s 62. In egon also thrived in that area—scoring 30— Des Moines, Iowa, June 6–9—For LSU, eight of the 14 previous editions, 62 would but balance couldn’t surmount LSU speed. it was like most years: an NCAA women’s have been enough, and it is the most the Moreover, Oregon soph English Gardner team title; for Oregon, it was like the previ- Ducks have ever scored. beat Duncan in the 100. Gardner’s time— ous three: Wait another year. Three-time defending champ Texas A&M against a 1.7 wind—was 11.10. That equates Led by rising superstar Kimberlyn Dun- was 3rd (38), and Kansas and Clemson shared to 10.98 with no wind. Duncan’s speed was the key to the Tiger team win MIKE SCOTT can, the Tigers exceeded projections to annex 4th with 28. Gardner also surprisingly led off the 4x4, their 15th title in 26 years. “You always think you could have done and Oregon chopped four seconds off the The Ducks, who have won the past three a little better here or done something a little school record to post the No. 2 time in colle- indoor titles, finished with a flourish, setting differently there, but in the end, 62 points— giate history. LSU, at 3:24.59, became No. 3. a meet record of 3:24.54 in the 4x4, but were the women had a pretty good meet,” Oregon After lowering her world 200 lead to a 2nd, as they were in ’09, ’10 and ’11. -

Men's Outdoor Record Book

2021 SEC MEN’S OUTDOOR TRACK AND FIELD RECORD BOOK All-Time SEC Team Champions 1975 Tennessee 215 Baton Rouge, La. Year Champion Pts Site 1976 Tennessee 179 Athens, Ga. 1933 LSU 73.5 Birmingham, Ala. 1977 Tennessee 168 Tuscaloosa, Ala. 1934 LSU 74.5 Birmingham, Ala. 1978 Tennessee 173 Knoxville, Tenn. 1935 LSU 78 Birmingham, Ala. 1979 Auburn 148 Tuscaloosa, Ala. 1936 LSU 60.5 Birmingham, Ala. 1980 Alabama 120 Auburn, Ala. 1937 Georgia 65 Birmingham, Ala. 1981 Tennessee 156 Gainesville, Fla. 1938 LSU 66 Birmingham, Ala. 1982 Tennessee 171.5 Athens, Ga. 1939 LSU 57 Birmingham, Ala. 1983 Tennessee 121 Lexington, Ky. 1940 LSU 69 Birmingham, Ala. 1984 Tennessee 112 Baton Rouge, La. 1941 LSU 49 Birmingham, Ala. 1985 Tennessee 129.5 Starkville, Miss. 1942 LSU 48 Birmingham, Ala. 1986 Tennessee 158 Knoxville, Tenn. 1943 LSU 50 Birmingham, Ala. 1987 Florida 133 Tuscaloosa, Ala. 1944 Georgia Tech 90 Birmingham, Ala. 1988 LSU 136 Auburn, Ala. 1945 Georgia Tech 93.75 Birmingham, Ala. 1989 LSU 164 Gainesville, Fla. 1946 LSU 54.5 Birmingham, Ala. 1990 LSU 137.3 Athens, Ga. 1947 LSU 52.5 Birmingham, Ala. 1991 Tennessee 183 Baton Rouge, La. 1948 LSU 41 Birmingham, Ala. 1992 Arkansas 176 Starkville, Miss. 1949 Georgia Tech 39.5 Birmingham, Ala. 1993 Arkansas 163 Knoxville, Tenn. 1950 Alabama 42.3 Birmingham, Ala. 1994 Arkansas 223 Fayetteville, Ark. 1951 LSU 47 Birmingham, Ala. 1995 Arkansas 171 Tuscaloosa, Ala. 1952 Alabama 38 Birmingham, Ala. 1996 Arkansas 170 Lexington, Ky. 1953 Florida 47.6 Birmingham, Ala. 1997 Arkansas 188 Auburn, Ala. 1954 Auburn 58 Birmingham, Ala. -

Teen Sensation Athing Mu

• ALL THE BEST IN RUNNING, JUMPING & THROWING • www.trackandfieldnews.com MAY 2021 The U.S. Outdoor Season Explodes Athing Mu Sets Collegiate 800 Record American Records For DeAnna Price & Keturah Orji T&FN Interview: Shalane Flanagan Special Focus: U.S. Women’s 5000 Scene Hayward Field Finally Makes Its Debut NCAA Formchart Faves: Teen LSU Men, USC Women Sensation Athing Mu Track & Field News The Bible Of The Sport Since 1948 AA WorldWorld Founded by Bert & Cordner Nelson E. GARRY HILL — Editor JANET VITU — Publisher EDITORIAL STAFF Sieg Lindstrom ................. Managing Editor Jeff Hollobaugh ................. Associate Editor BUSINESS STAFF Ed Fox ............................ Publisher Emeritus Wallace Dere ........................Office Manager Teresa Tam ..................................Art Director WORLD RANKINGS COMPILERS Jonathan Berenbom, Richard Hymans, Dave Johnson, Nejat Kök SENIOR EDITORS Bob Bowman (Walking), Roy Conrad (Special AwaitsAwaits You.You. Projects), Bob Hersh (Eastern), Mike Kennedy (HS Girls), Glen McMicken (Lists), Walt Murphy T&FN has operated popular sports tours since 1952 and has (Relays), Jim Rorick (Stats), Jack Shepard (HS Boys) taken more than 22,000 fans to 60 countries on five continents. U.S. CORRESPONDENTS Join us for one (or more) of these great upcoming trips. John Auka, Bob Bettwy, Bret Bloomquist, Tom Casacky, Gene Cherry, Keith Conning, Cheryl Davis, Elliott Denman, Peter Diamond, Charles Fleishman, John Gillespie, Rich Gonzalez, Ed Gordon, Ben Hall, Sean Hartnett, Mike Hubbard, ■ 2022 The U.S. Nationals/World Champion- ■ World Track2023 & Field Championships, Dave Hunter, Tom Jennings, Roger Jennings, Tom ship Trials. Dates and site to be determined, Budapest, Hungary. The 19th edition of the Jordan, Kim Koffman, Don Kopriva, Dan Lilot, but probably Eugene in late June. -

USATF Cross Country Championships Media Handbook

TABLE OF CONTENTS NATIONAL CHAMPIONS LIST..................................................................................................................... 2 NCAA DIVISION I CHAMPIONS LIST .......................................................................................................... 7 U.S. INTERNATIONAL CROSS COUNTRY TRIALS ........................................................................................ 9 HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS ........................................................................................ 20 APPENDIX A – 2009 USATF CROSS COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS ............................................... 62 APPENDIX B –2009 USATF CLUB NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS .................................................. 70 USATF MISSION STATEMENT The mission of USATF is to foster sustained competitive excellence, interest, and participation in the sports of track & field, long distance running, and race walking CREDITS The 30th annual U.S. Cross Country Handbook is an official publication of USA Track & Field. ©2011 USA Track & Field, 132 E. Washington St., Suite 800, Indianapolis, IN 46204 317-261-0500; www.usatf.org 2011 U.S. Cross Country Handbook • 1 HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS USA Track & Field MEN: Year Champion Team Champion-score 1954 Gordon McKenzie New York AC-45 1890 William Day Prospect Harriers-41 1955 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-28 1891 M. Kennedy Prospect Harriers-21 1956 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-46 1892 Edward Carter Suburban Harriers-41 1957 John Macy New York AC-45 1893-96 Not Contested 1958 John Macy New York AC-28 1897 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-31 1959 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-30 1898 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-42 1960 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-33 1899-1900 Not Contested 1961 Bruce Kidd Houston TFC-35 1901 Jerry Pierce Pastime AC-20 1962 Pete McArdle Los Angeles TC-40 1902 Not Contested 1963 Bruce Kidd Los Angeles TC-47 1903 John Joyce New York AC-21 1964 Dave Ellis Los Angeles TC-29 1904 Not Contested 1965 Ron Larrieu Toronto Olympic Club-40 1905 W.J.