A Sermon Preached by the Bishop of Coventry, Christopher Cocksworth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magna Charta, 1215

Magna Charta, 1215 JOHN, by the grace of God King of England, Lord of Ireland, Duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, and Count of Anjou, to his archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, barons, justices, foresters, sheriffs, stewards, servants, and to all his officials and loyal subjects, Greeting. KNOW THAT BEFORE GOD, for the health of our soul and those of our ancestors and heirs, to the honour of God, the exaltation of the holy Church, and the better ordering of our kingdom, at the advice of our reverend fathers Stephen, archbishop of Canterbury, primate of all England, and cardinal of the holy Roman Church, Henry archbishop of Dublin, William bishop of London, Peter bishop of Winchester, Jocelin bishop of Bath and Glastonbury, Hugh bishop of Lincoln, Walter Bishop of Worcester, William bishop of Coventry, Benedict bishop of Rochester, Master Pandulf subdeacon and member of the papal household, Brother Aymeric master of the knighthood of the Temple in England, William Marshal earl of Pembroke, William earl of Salisbury, William earl of Warren, William earl of Arundel, Alan de Galloway constable of Scotland, Warin Fitz Gerald, Peter Fitz Herbert, Hubert de Burgh seneschal of Poitou, Hugh de Neville, Matthew Fitz Herbert, Thomas Basset, Alan Basset, Philip Daubeny, Robert de Roppeley, John Marshal, John Fitz Hugh, and other loyal subjects: (1) FIRST, THAT WE HAVE GRANTED TO GOD, and by this present charter have confirmed for us and our heirs in perpetuity, that the English Church shall be free, and shall have its rights undiminished, and its liberties unimpaired. That we wish this so to be observed, appears from the fact that of our own free will, before the outbreak of the present dispute between us and our barons, we granted and confirmed by charter the freedom of the Church's elections - a right reckoned to be of the greatest necessity and importance to it - and caused this to be confirmed by Pope Innocent III. -

Welcome to Praxis Praxis South Events for 2018: He Church Exists to Worship God

Welcome to Praxis Praxis South Events for 2018: he church exists to worship God. Worship is the only activity of the Church Getting ready for the Spirit! Twhich will last into eternity. Speaker: the Rev’d Aidan Platten Bless your enemies; pray for those Worship enriches and transforms our lives. In Christ we An occasion to appreciate some of the last liturgical are drawn closer to God in the here and now. thoughts of the late Michael Perham. who persecute you: Worship to This shapes our beliefs, our actions and our way of life. God transforms us as individuals, congregations Sacraments in the Community mend and reconcile. and communities. Speaker: The Very Rev’d Andrew Nunn, Dean of Worship provides a vital context for mission, teaching Southwark and pastoral care. Good worship and liturgy inspires A day exploring liturgy in a home setting e.g. confession, and attracts, informs and delights. The worship of God last rites, home communion can give hope and comfort in times of joy and of sorrow. Despite this significance, we are often under-resourced Please visit our updated website for worship. Praxis seeks to address this. We want to www.praxisworship.org.uk encourage and equip people, lay and ordained, to create, to keep up-to-date with all Praxis events, and follow the lead and participate in acts of worship which enable links for Praxis South. transformation to happen in individuals and communities. What does Praxis do to offer help? Praxis offers the following: � training days and events around the country (with reduced fees for members and no charge for ordinands or Readers-in-training, or others in recognised training for ministry) � key speakers and ideas for diocesan CME/CMD Wednesday 1 November 2017 programmes, and resources for training colleges/courses/ 10.30 a.m. -

Coventry Diocesan Board of Finance Limited

COVENTRY DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE LIMITED REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS for the year ended 31 December 2016 Company Registered Number: 319482 Registered Charity Number: 247828 COVENTRY DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE LIMITED REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS for the year ended 31 December 2016 Coventry Diocesan Board of Finance Limited: serving the Diocese of Coventry The Diocese of Coventry is one of 42 dioceses in the Church of England. Re-founded in 1918 but with a history dating back to 658, the diocese has an overall population of approximately 900,000 and covers an area of just under 700 square miles, covering Coventry, most of Warwickshire and a small part of Solihull. The diocese is sub-divided into 11 areas called deaneries and, overall, includes 200 parishes. Some parishes have more than one church - the diocese has 238 churches open for public worship. The diocese has one Cathedral – The Cathedral Church of St Michael, Coventry. Each diocese is led by a Diocesan Bishop. The Right Reverend Doctor Christopher Cocksworth became Bishop of Coventry in 2008. Shortly after his installation he re-affirmed the diocesan mission as one of worshipping God, making new disciples and transforming communities. The diocesan strategy to achieve this is by focussing on eight qualities essential for healthy growing churches: empowering leadership; gift-orientated ministry; passionate spirituality; inspiring worship; holistic small groups; need-orientated outreach; loving relationships; and functional structures. The Coventry Diocesan Board of Finance Limited (“the DBF”) was established under the Diocesan Boards of Finance Measure 1925 and is both a company limited by guarantee and a registered charity. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2021

PORVOO PRAYER DIARY 2021 The Porvoo Declaration commits the churches which have signed it ‘to share a common life’ and ‘to pray for and with one another’. An important way of doing this is to pray through the year for the Porvoo churches and their Dioceses. The Prayer Diary is a list of Porvoo Communion Dioceses or churches covering each Sunday of the year, mindful of the many calls upon compilers of intercessions, and the environmental and production costs of printing a more elaborate list. Those using the calendar are invited to choose one day each week on which they will pray for the Porvoo churches. It is hoped that individuals and parishes, cathedrals and religious orders will make use of the Calendar in their own cycle of prayer week by week. In addition to the churches which have approved the Porvoo Declaration, we continue to pray for churches with observer status. Observers attend all the meetings held under the Agreement. The Calendar may be freely copied or emailed for wider circulation. The Prayer Diary is updated once a year. For corrections and updates, please contact Ecumenical Officer, Maria Bergstrand, Ms., Stockholm Diocese, Church of Sweden, E-mail: [email protected] JANUARY 3/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Sarah Mullally, Bishop Graham Tomlin, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Rob Wickham, Bishop Jonathan Baker, Bishop Ric Thorpe, Bishop Joanne Grenfell. Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Olav Fykse Tveit, Bishop Herborg Oline Finnset 10/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Jukka Keskitalo Church of Norway: Diocese of Sør-Hålogaland (Bodø), Bishop Ann-Helen Fjeldstad Jusnes Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Christopher Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. -

Churchof England

THE Bishops take the knee BISHOPS across the country led Angli- The Rt Rev Guli Francis-Dehqani, said: cans in ‘taking the knee’ to mark the “We must stand up and share our abhorrence death of American George Floyd and to of that racist brutality but also act in our own CHURCHOF highlight injustice in British society. areas to address the culture of discrimination The Bishop of Leicester, the Rt Rev Martyn we live in this society too.” Snow, led others in kneeling for eight min- Meanwhile the Bishop of Coventry, the Rt utes and 46 seconds, the length of time that a Rev Dr Christopher Cocksworth, and the ENGLAND US police officer knelt on Mr Floyd’s neck. Bishop of Warwick, the Rt Rev John Stroyan Bishop Snow said: “I am deeply shocked by ‘took the knee’ in front of the Charred Cross the appalling brutality we have seen against in the Cathedral Ruins. Newspaper black people in America and I stand along- In Manchester hundreds of people joined side those who are suffering and peacefully in a ‘Protest through Prayer’ event as a form calling for urgent change, as well as commit- of action in solidarity with #BlackLivesMatter ting to make changes in our own lives and organised by the Archdeacon of Manchester. the institutions we are part of. This week the Archbishop of Canterbury 12 June, 2020 “Structural and systemic racial prejudice said: “The racism that people in this country £1.50 exists across societies and institutions and experience is horrifying. The Church has No: 6539 we must act to change that, as well as failed here, and still does, and it’s clear what Established in 1828 addressing our own unconscious biases that Jesus commands us to do: repent and take lead us to discriminate against others.” Earli- action.” er this year he led the General Synod in a Download our App on vote to apologise for racism in the Church. -

Final Details

Diocesan Centenary 2018 Pilgrimage of the DBE Cross of Nails FINAL DETAILS Introduction A pilgrimage of the DBE Cross of Nails will take place as it did in 2011 when we celebrated the bi- centenary of Church of England schools. A timetable for this has been confirmed and is attached with this information sheet. Instructions for the Pilgrimage The Start of the Pilgrimage The pilgrimage begins in the ruins of our Cathedral on 10 January 2018 with the diocesan Cross of Nails being presented to students of Harris CofE Academy. The cross is then passed from school to school throughout the year (see the attachment showing the route). The Journey of the Cross of Nails The Headteacher of the ‘giving’ school must take responsibility for making arrangements with the ‘receiving’ school for passing on the Cross of Nails. When receiving the Cross of Nails from the preceding school please ensure that there are pupils from your school ready to share in the Diocesan Centenary Prayer that will be spoken together with those children handing over the Cross of Nails to your school. Diocesan Centenary Prayer Loving God, thank you for every moment, past and present And for your care of our diocese through 100 years. As we celebrate all you’re doing here Help us to make good choices for the future, And to accept your gifts so we may do your work Of love and reconciliation day by day, through Jesus Christ our Lord. You may also wish to involve those children in sharing together in the Coventry Litany of Reconciliation Page 2 of 6 Litany of Reconciliation Adapted -

Supporting Papers for the Faith and Order Commission Report, Communion and Disagreement

SUPPORTING PAPERS FOR THE FAITH AND ORDER COMMISSION REPORT, COMMUNION AND DISAGREEMENT 1 Copyright © The Archbishops’ Council 2016 2 Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................................. 5 1 Communion, Disagreement and Conscience Loveday Alexander and Joshua Hordern ........................................................................................ 6 Listening to Scripture ..................................................................................................................... 6 Conscience: Points of Agreement ................................................................................................ 9 Conscience and Persuasion in Paul – Joshua Hordern .......................................................... 10 Further Reflections – Loveday Alexander .................................................................................. 15 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................ 17 2 Irenaeus and the date of Easter Loveday Alexander and Morwenna Ludlow ................................................................................ 19 Irenaeus and the Unity of the Church – Loveday Alexander ................................................ 19 A Response – Morwenna Ludlow.................................................................................................. 23 Further Reflections – Loveday -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Graeme Pringle To: News desk From: Communication Officer for the Diocese of Coventry Date: 07 MAR 2013 Email: [email protected] Office: 024 7452 1336 Mobile: 07507 196 495 Bishop of Coventry makes his maiden speech in the House of Lords The Bishop of Coventry, the Right Reverend Dr Christopher Cocksworth, has used his maiden speech in the House of Lords to pay tribute to the vital role of women in Coventry and Warwickshire. “The Church will need their like to guide its life as our Bishops in the future”, he said. Bishop Christopher also spoke about the great relevance of Coventry’s history to the world today. He called for the centenary anniversary of the First World War to remember that the tears of German widows and mothers flowed with the same agony as those of British and Commonwealth women. He concluded by saying, “It is alongside and with our former enemy who is now our friend that we reflect with Germany and our European partners on the impact of war on our continent and share a commitment to work for a reconciled and peaceful future for the world.” On the eve of International Women’s Day, Bishop Christopher spoke about women who work tirelessly and with great skill for the good of their communities. He began by paying tribute to his “excellent women clergy colleagues who give of themselves with extraordinary dedication to the people of Coventry and Warwickshire”. Bishop Christopher then said: “The common life of Coventry and Warwickshire depends on the leadership of women in every other sphere – in political and civic life, in business activity and public institutions, in the arts and sport, and in the myriad of charities and agencies that care for those in need and raise the quality of our life together. -

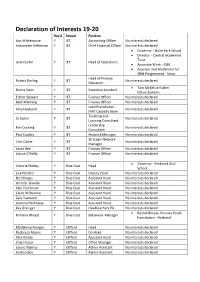

Declaration of Interests 19-20

Declaration of Interests 19-20 Rec'd School Position Lois Whitehouse Y IET Accounting Officer No interests declared Antoinette Heffernan Y IET Chief Financial Officer No interests declared Governor - Stoke Park School Director – Central Academies Trust Jane Durkin Y IET Head of Operations Associate Work – ISBL Assessor and Moderator for SBM Programmes - Serco Head of Primary Robert Darling Y IET No interests declared Education Tom McKelvie Father Emma Dean Y IET Executive Assistant Dalvie Systems Esther Stewart Y IET Finance Officer No interests declared Beth Manning Y IET Finance Officer No interests declared Lead Practitioner - Amy Husband Y IET No interests declared MAT Capacity team Teaching and Jo Upton Y IET No interests declared Learning Consultant Leadership Kim Docking Y IET No interests declared Consultant Paul Cowley Y IET Network Manager No interests declared Strategic Network Tom Carter Y IET No interests declared Manager Laura Bee Y IET Finance Officer No interests declared Louise O'Reilly Y IET Finance Officer No interests declared Governor - Frederick Bird Victoria Shelley Y Blue Coat Head School Lisa Henden Y Blue Coat Deputy Head No interests declared Neil Phipps Y Blue Coat Assistant Head No interests declared Jennifer Davoile Y Blue Coat Assistant Head No interests declared Alex Tomlinson Y Blue Coat Assistant Head No interests declared Claire Milbourne Y Blue Coat Assistant Head No interests declared Zara Yasmeen Y Blue Coat Assistant Head No interests declared Gemma Hathaway Y Blue Coat Assistant Head No interests -

Anglican Chaplain

The Diocese of Coventry and The University of Warwick Anglican Chaplain Background The University of Warwick is widely recognised as one of the UK’s leading Universities. Ranked 3rd in the world amongst the top 50 universities under 50 years of age (QS table for 2013 and 2014), it is a teaching and research community of approximately 24,000 students and 5000 staff, led by Vice-Chancellor Professor Nigel Thrift. The Chaplaincy Centre, situated at the very heart of the campus, serves as a place of welcome, meeting, engagement, prayer and stillness within the busy campus community. With a significant contingent of international students (approximately one-third of the overall student population), the community is a diverse one. As part of the worldwide Coventry Cross of Nails community, the Chaplaincy works with Coventry Cathedral to build peace through understanding. Promoting tolerance and reconciliation, the Chaplaincy proudly celebrates Warwick’s diversity. The Diocese of Coventry covers Coventry, Warwickshire and a part of Solihull and is led by the ninth Bishop of Coventry, the Right Reverend Dr Christopher Cocksworth. The themes of Peace and Reconciliation form a distinctive part of the heritage of the city, Cathedral, Diocese of Coventry, and the University. Coventry Cathedral has a world renowned reputation for promoting peace and reconciliation, and the Chaplaincy, as part of the Cross of Nails community, seeks to embody and share this calling within the university community. The Chaplaincy is both a place and a team of people, serving students and staff of all faiths and none. A recent (2012/13) review of the Chaplaincy underlines the outstanding contribution that the work of the Chaplaincy makes to the University community. -

GENERAL SYNOD February 2014 QUESTIONS of Which Notice Has Been Given Under Standing Orders 105-109

GENERAL SYNOD February 2014 QUESTIONS of which notice has been given under Standing Orders 105-109. Questions for written reply are marked with an asterisk. INDEX QUESTIONS 1-8 BATH & WELLS SEE HOUSE Housing for Bishop of Bath & Wells: timing of announcement Q1 Housing for Bishop of Bath & Wells: publication of relevant minutes Q2 Housing for Bishop of Bath & Wells: Commissioners‟ statement Q3 Housing for Bishop of Bath & Wells: suitability of current housing Q4-5 Housing for Bishop of Bath & Wells: Board consideration Q6 Housing for Bishop of Bath & Wells: financial implications Q7 Review of Church Commissioners‟ decisions Q8 QUESTIONS 9-20 HOUSE OF BISHOPS Theos report on mission of cathedrals Q9 Status of ACNA Q10 Pastoral care and support of homosexual people Q11 Sexuality: facilitated conversations Q12-14 Status of same-sex marriages Q15 Guidance re Reparative or Conversion therapies Q16 Common Awards: alternative validation route Q17 Showing of potentially blasphemous cinematic material Q18 Linkage between clergy skills and church growth Q19 Communicating Christian Faith to under 30s Q20 QUESTION 21 SECRETARY GENERAL PCCs & Chancel Repair Liability Q21 QUESTIONS 22-29 BOARD OF EDUCATION Homophobic bullying in schools: availability of materials to combat it Q22 Data on bullying in schools: role for DBEs Q23 Homophobic bullying in schools Q24 C of E Youth Council: 10th anniversary Q25 Review of RE Council Report on religious education Q26 Provision for children, young people and families Q27 Checks on appointments in Church Schools -

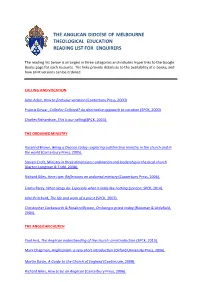

Reading List.Pdf

THE ANGLICAN DIOCESE OF MELBOURNE THEOLOGICAL EDUCATION READING LIST FOR ENQUIRERS The reading list below is arranged in three categories and includes hyperlinks to the Google Books page for each resource. The links provide details as to the availability of e-books, and how print versions can be ordered. CALLING AND VOCATION John Adair, How to find your vocation (Canterbury Press, 2000) Francis Dewar, Called or Collared? An alternative approach to vocation (SPCK, 2000) Charles Richardson, This is our calling(SPCK, 2003). THE ORDAINED MINISTRY Rosalind Brown, Being a Deacon today: exploring a distinctive ministry in the church and in the world (Canterbury Press, 2005). Steven Croft, Ministry in three dimensions: ordination and leadership in the local church (Darton Longman & Todd, 2008). Richard Giles, Here I am: Reflections on ordained ministry (Canterbury Press, 2006). Emma Percy. What clergy do: Especially when it looks like nothing (London: SPCK, 2014). John Pritchard, The life and work of a priest (SPCK, 2007). Christopher Cocksworth & Rosalind Brown, On being a priest today (Rowman & Littlefield, 2004). THE ANGLICAN CHURCH Paul Avis, The Anglican understanding of the church: an introduction (SPCK, 2013). Mark Chapman, Anglicanism: a very short introduction (Oxford University Press, 2006). Martin Davie, A Guide to the Church of England (Continuum, 2008). Richard Giles, How to be an Anglican (Canterbury Press, 2006). Bruce Kaye, A church without walls: being Anglican in Australia (Dove, 1995). Stephen Spencer. Anglicanism (SCM, 2010). Christopher Webber, Welcome to the Episcopal church: an introduction to its history, faith and worship (Church Publishing, 1999). Rowan Williams, Anglican identities (Rowman & Littlefield, 2003).