Silent Witnesses : Re-Interpreting the Still Life Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faith Ringgold the Studiowith and Quilts That Tell Stories ART HIST RY KIDS

Faith Ringgold The Studiowith and quilts that tell stories ART HIST RY KIDS THE GOLDEN AGE IN AFRICAN AMERICAN CULTURE Art is connected to everything... music, history, science, math, literature, and more! Let’s explore how this month‘s art relates to some of these subjects. What is the Harlem Renaissance? From the 1910’s - the 1930’s the northern Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem was booming with creativity. From fashion to food, music to dance, literature to art... amazing things were happening around every corner. This map illustrates the concentration of jazz clubs, restau- rants, and theaters in Harlem. As we spend this week connecting Faith Ringgold’s art to these other subjects, we’ll use her book, Harlem Renaissance Party, as our guide. Faith Ringgold’s book, Harlem Renaissance Party, takes us on a tour of the rich literary, culinary, musical, and theatrical scene in Harlem during the 1930’s. The following pages explore the Harlem Renaissance as Ringgold describes it in her book (and she should know, because she was actually there!) Click the image above to see a story time reading of the book! Illustration by Elmer Simms Campbell | Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library February 2019 | Week 3 1 Faith Ringgold The Studiowith and quilts that tell stories ART HIST RY KIDS CONNECTING THE DOTS Geography The United States of America Here are maps of The United States of America, New York state, and Harlem – a neighborhood in the Manhattan borough of New New York State York City. February 2019 | Week 3 2 Faith Ringgold The Studiowith and quilts that tell stories ART HIST RY KIDS CONNECTING THE DOTS Literature - Poetry + Folk Tales Langston Hughes Zora Neale Hurston 1936 photo by Carl Van Vechten Langston Hughes was one of the strongest Zora Neale Hurston wrote Mules and Men – literary voices during the Harlem Renaissance. -

Oral History Interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12

Oral history interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12 Funding for this interview was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Ann Wilson on 2009 April 19-2010 July 12. The interview took place at Wilson's home in Valatie, New York, and was conducted by Jonathan Katz for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ANN WILSON: [In progress] "—happened as if it didn't come out of himself and his fixation but merged. It came to itself and is for this moment without him or her, not brought about by him or her but is itself and in this sudden seeing of itself, we make the final choice. What if it has come to be without external to us and what we read it to be then and heighten it toward that reading? If we were to leave it alone at this point of itself, our eyes aging would no longer be able to see it. External and forget the internal ordering that brought it about and without the final decision of what that ordering was about and our emphasis of it, other eyes would miss the chosen point and feel the lack of emphasis. -

3-4 Booklist by Title - Full

3-4 Booklist by Title - Full When using this booklist, please be aware of the need for guidance to ensure students select texts considered appropriate for their age, interest and maturity levels. PRC Title/Author Publisher Year ISBN Annotations 9404 100 Australian poems for children Random House 2002 9781740517751 From emus to magic puddings, this feast of Australian poems for Griffith, Kathryn & Scott-Mitchell, Claire (eds)Australia Pty Ltd children is fresh and familiar. Written by grown-ups and kids, with & Rogers, Gregory (ill) beautiful illustrations, it reveals what is special about growing up in Australia. 660416 100 ways to fly University of 2019 9780702262500 In 100 Ways to Fly you'll find a poem for every mood - poems to make Taylor, Michelle Queensland Press you laugh, feel silly or to twist your tongue, to make you courageous enough for a new adventure or to help you soar. 537 27th annual African hippopotamus race Puffin Australia 1985 9780140309911 Go behind the scenes as eight year old Edward, the hippopotamus, Lurie, Morris trains for the greatest swimming marathon of all. 18410 4F for freaks Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd 2006 9781741140910 4F pride themselves on frightening teachers out of the classroom. It Hobbs, Leigh seems that they have met their match with Miss Corker who has a few tricks of her own up her sleeves. 9581 500 hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Random House 1989 9780394844848 Bartholomew is selling cranberries when the king passes by. A big cry is Seuss, Dr Australia Pty Ltd heard, 'Hats off to the King', which Bartholomew does but he still has a hat on his head. -

Cascades Female Factory South Hobart Conservation Management Plan

Cascades Female Factory South Hobart Conservation Management Plan Cascades Female Factory South Hobart Conservation Management Plan Prepared for Tasmanian Department of Environment, Parks, Heritage and the Arts April 2008 Table of contents Table of contents i List of figures iii List of Tables v Project Team vi Acknowledgements vii Executive Summary ix 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to project 2 1.2 History & Limitations on Approach 2 1.3 Description 3 1.4 Key Reports & References 4 1.5 Heritage listings & controls 12 1.6 Site Management 13 1.7 Managing Heritage Significance 14 1.8 Future Management 15 2.0 Female Factory History 27 2.1 Introduction 27 2.2 South Hobart 28 2.3 Women & Convict Transportation: An Overview 29 2.4 Convict Women, Colonial Development & the Labour Market 30 2.5 The Development of the Cascades Female Factory 35 2.6 Transfer to the Sheriff’s Department (1856) 46 2.7 Burial & Disinterment of Truganini 51 2.8 Demolition and subsequent history 51 2.9 Conclusion 52 3.0 Physical survey, description and analysis 55 3.1 Introduction 55 3.2 Setting & context 56 3.3 Extant Female Factory Yards & Structures 57 3.4 Associated Elements 65 3.5 Archaeological Resource 67 3.6 Analysis of Potential Archaeological Resource 88 3.7 Artefacts & Movable Cultural Heritage 96 4.0 Assessment of significance 98 4.1 Introduction 98 4.2 Brief comparative analysis 98 4.3 Assessment of significance 103 5.0 Conservation Policy 111 5.1 Introduction 111 5.2 Policy objectives 111 LOVELL CHEN i 5.3 Significant site elements 112 5.4 Conservation -

Aca Galleriesest. 1932

EST. 1932 ACA GALLERIES Faith Ringgold Courtesy of ACA Galleries Faith Ringgold, American People Series #19: U.S. Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power, 1967 th ACA GALLERIES 529 West 20 Street New York, NY 10011 | t: 212-206-8080 | e: [email protected] | acagalleries.com EST. 1932 ACA GALLERIES The Enduring Power of Faith Ringgold’s Art By Artsy Editors Aug 4, 2016 4:57 pm Portrait of Faith Ringgold. Photo by Grace Matthews. In 1967, a year of widespread race riots in America, Faith Ringgold painted a 12-foot-long canvas called American People Series #20: Die. The work shows a tumult of figures, both black and white, wielding weapons and spattered with blood. It was a watershed year for Ringgold, who, after struggling for a decade against the marginalization she faced as a black female artist, unveiled the monumental piece in her first solo exhibition at New York’s Spectrum Gallery. Earlier this year, several months after Ringgold turned 85, the painting was purchased by the Museum of Modern Art, cementing her legacy as a pioneering artist and activist whose work remains searingly relevant. Where did she come from? Ringgold was born in Harlem in 1930. Her family included educators and creatives, and she grew up surrounded by the Harlem Renaissance. The street where she was raised was also home to influential activists, writers, and artists of the era—Thurgood Marshall, W.E.B. Dubois, and Aaron Douglas, to name a few. “It’s nice th ACA GALLERIES 529 West 20 Street New York, NY 10011 | t: 212-206-8080 | e: [email protected] | acagalleries.com EST. -

Dear Sister Artist: Activating Feminist Art Letters and Ephemera in the Archive

Article Dear Sister Artist: Activating Feminist Art Letters and Ephemera in the Archive Kathy Carbone ABSTRACT The 1970s Feminist Art movement continues to serve as fertile ground for contemporary feminist inquiry, knowledge sharing, and art practice. The CalArts Feminist Art Program (1971–1975) played an influential role in this movement and today, traces of the Feminist Art Program reside in the CalArts Institute Archives’ Feminist Art Materials Collection. Through a series of short interrelated archives stories, this paper explores some of the ways in which women responded to and engaged the Collection, especially a series of letters, for feminist projects at CalArts and the Women’s Art Library at Goldsmiths, University of London over the period of one year (2017–2018). The paper contemplates the archive as a conduit and locus for current day feminist identifications, meaning- making, exchange, and resistance and argues that activating and sharing—caring for—the archive’s feminist art histories is a crucial thing to be done: it is feminism-in-action that not only keeps this work on the table but it can also give strength and definition to being a feminist and an artist. Carbone, Kathy. “Dear Sister Artist,” in “Radical Empathy in Archival Practice,” eds. Elvia Arroyo- Ramirez, Jasmine Jones, Shannon O’Neill, and Holly Smith. Special issue, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3. ISSN: 2572-1364 INTRODUCTION The 1970s Feminist Art movement continues to serve as fertile ground for contemporary feminist inquiry, knowledge sharing, and art practice. The California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) Feminist Art Program, which ran from 1971 through 1975, played an influential role in this movement and today, traces and remains of this pioneering program reside in the CalArts Institute Archives’ Feminist Art Materials Collection (henceforth the “Collection”). -

A Stitch Between

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2020 A Stitch Between Erin Elizabeth Bundock Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Bundock, Erin Elizabeth, "A Stitch Between" (2020). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 338. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/338 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Stitch Between Erin Bundock Undergraduate Honors Thesis Studio Art May 17, 2020 Defense Date: April 30, 2020 Thesis Examination Committee: Steve Budington, MFA, Advisor Jane Kent, BFA, Advisor Deborah Ellis, MFA, Chair Abstract As an artist I am compelled to tell stories about intimate moments, both tender and tense. Over the past year, the exhibition, A Stitch Between, has developed into a meditation on relationships with the self and others. This project includes a series of three portraits and a grouping of felt objects. These were created through a variety of processes, including printing, drawing, painting, and sewing. This formal combination mirrors the complexity of relationships surrounding sexuality and reproductive health that is the undercurrent of the work. Utilizing fiber’s associations with femininity and its ties to feminine resistance, A Stitch Between -

How Collaboration and Collectivism in Australia in the Seventies Helped

A Collaborative Effort: How Collaboration and Collectivism in Australia in the Seventies Helped Transform Art into the Contemporary Era Susan Rothnie Introduction The seventies period in Australia is often referred to as the “anything goes” decade. It is a label that gives a sense of the profusion of anti- establishment modes that emerged in response to calls for social and po- litical change that reverberated around the globe around that time. As a time of immense change in the Australian art scene, the seventies would influence the development of art into the contemporary era. The period‟s diversity, though, has presented difficulty for Australian art historiography. Despite the flowering of arts activity during the seventies era—and proba- bly also because of it—the period remains largely unaccounted for by the Australian canon. In retrospect, the seventies can be seen as a period of crucial impor- tance for Australia‟s embrace of contemporary art. Many of the tendencies currently identified with the contemporary era—its preoccupation with the present moment, awareness of the plurality of existence, rejection of hier- archies, resistance to hegemonic domination, and a sense of a global community—were inaugurated during the seventies period. Art-historically, COLLOQUY text theory critique 22 (2011). © Monash University. www.arts.monash.edu.au/ecps/colloquy/journal/issue022/rothnie.pdf 166 Susan Rothnie ░ however, it appears as a “gap” in the narration of Australian art‟s develop- ment which can be explained neither by the modernism which preceded it, nor by postmodernism. In Australia, the seventies saw a rash of new art “movements” emerge almost simultaneously. -

Tasmanian Family History Society Inc

TASMANIAN FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY INC. Volume 34 Number 3—December 2013 TASMANIAN FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY INC. PO Box 326 Rosny Park Tasmania 7018 Society Secretary: [email protected] Journal Editor: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.tasfhs.org Patron: Dr Alison Alexander Fellows: Dr Neil Chick and Mr David Harris Executive: President Maurice Appleyard (03) 6248 4229 Vice President Robert Tanner (03) 6231 0794 Vice President Pam Bartlett (03) 6428 7003 Society Secretary Colleen Read (03) 6244 4527 Society Treasurer Peter Cocker (03) 6435 4103 Committee: Helen Anderson Betty Bissett Vanessa Blair Judith Cocker Geoffrey Dean Lucille Gee John Gillham Libby Gillham Julie Kapeller Dale Smith By-laws Coordinator Robert Tanner (03) 6231 0794 Webmaster Robert Tanner (03) 6231 0794 Journal Editor Rosemary Davidson (03) 6424 1343 LWFHA Coordinator Lucille Gee (03) 6344 7650 Members’ Interests Compiler John Gillham (03) 6239 6529 Membership Registrar Muriel Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Publications Convenor Bev Richardson (03) 6225 3292 Public Officer Colleen Read (03) 6244 4527 Society Sales Officer Maurice Appleyard (03) 6245 9351 Branches of the Society Burnie:PO Box 748 Burnie Tasmania 7320 [email protected] Mersey:PO Box 267 Latrobe Tasmania 7307 [email protected] Hobart:PO Box 326 Rosny Park Tasmania 7018 [email protected] Huon:PO Box 117 Huonville Tasmania 7109 [email protected] Launceston:PO Box 1290 Launceston Tasmania 7250 [email protected] Volume 34 Number 3 December 2013 ISSN 0159 0677 Contents From the editor -

Trudy Cowley & Dianne Snowden

Trudy Cowley & Dianne Snowden, Patchwork Prisoners: the Rajah Quilt and the women who made it, Hobart: Research Tasmania, 2013. 326 pages, includes Index and Bibliography The ship Rajah arrived in Hobart in 1841 with a cargo of female prisoners, and the patchwork quilt made by some of them. This book tells their story, and the authors, both well‐known historians, have left no stone unturned to cover every aspect of it. In doing so, they have skilfully set the voyage, the quilt and the women in the context of their times. There is fascinating information about the quilt, with excellent material about Elizabeth Fry and her Ladies’ Committee, who provided not only materials for the quilt, but a matron (Keziah Hayter) to supervise making it. The authors suggest identifications of quilters among the convicts, with those who acknowledged sewing skills more likely. All convicts on board are described: their crimes, their native places, their descriptions, ages, height and background, for example whether they were ‘on the town’. The trip out is also described, and what happened to the women when they arrived: where and to whom they were assigned, their experiences, any further offences. Many lived in institutions, such as female factories, hiring depots and hospitals. Many women married, and this is covered in detail: how many were already married in Britain, colonial marriages, children – and those who did not marry, and who had same‐sex relationships. Women’s lives after sentence are described – their jobs, their marriages, family life, in chapters entitled ‘Freedom’ and ‘Surviving’. Then comes death, which is analysed in detail: the cause, age, place, and memorials for the women. -

Women of Color As Artists

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1996 Volume III: Race and Representation in American Cinema Women of Color as Artists Curriculum Unit 96.03.09 by Val-Jean Belton The New Haven public school system is a melting pot of many different cultures. The Fair Haven Middle school where I am one of two art teachers, is culturally very diverse. The student body is 65% Hispanic, 25% African American, and 10% White or other. I have observed that these students have little appreciation for visual arts. By offering lessons that center on various themes that are associated with their cultural heritage, I am able to gain and retain their attention. My lessons are taught in this particular manner in the hope that my students might better understand each others’ cultural heritage through hands-on experience in art. Despite my efforts to develop and teach art lessons that are not only culturally enriching but offer hands-on experience, I have had a tendency not to include information about the vast number of women artists. I have especially failed to include African American and Hispanic women artists who have contributed to our cultural experience. Although women artists have made major contributions to the art world, the extent of their accomplishments have been overshadowed by male artists such as Pablo Picasso, Jacob Lawrence, and Henri Matisse. There is little information available concerning women artists of African American and Hispanic descents available in our art curriculum, so they have not been included in the visual art classes that I teach. -

'Everywhere About

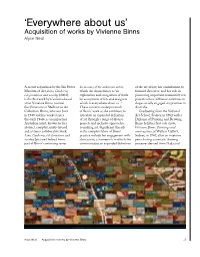

‘Everywhere about us’ Acquisition of works by Vivienne Binns Alyce Neal A recent acquisition by the Ian Potter In memory of the unknown artist, of the art object; her contribution to Museum of Art, Lino, Canberra, which she characterises as ‘an feminist discourse; and her role in tile formation and overlay (2001), exploration and recognition of work pioneering important community arts is the first work by Canberra-based by anonymous artists and designers projects whose influence continues to artist Vivienne Binns to enter which is everywhere about us’.1 shape socially engaged art practices in the University of Melbourne Art These concerns underpin much Australia. Collection. Binns, who was born of Binns’ work as she continues to Graduating from the National in 1940 and has worked since articulate an expanded definition Art School, Sydney, in 1962 with a the early 1960s, is an important of art through a range of diverse Diploma of Painting and Drawing, Australian artist, known for her projects and inclusive approaches Binns held her first solo show, abstract, complex, multi-layered to making art. Significant threads Vivienne Binns: Paintings and and at times collaborative work. in the complex fabric of Binns’ constructions, at Watters Gallery, Lino, Canberra, tile formation and practice include her engagement with Sydney, in 1967, after an intensive overlay (pictured below) forms abstraction, a framework in which she period using automatic drawing part of Binns’ continuing series communicates an expanded definition processes derived from Dada and Alyce Neal Acquisition of works by Vivienne Binns 25 Previous page: Vivienne Binns, Lino, Canberra, Below: Vivienne Binns, Connections in tile formation and overlay, 2001, linoleum, autumn with Vivienne, 2017, acrylic on paper, wood, synthetic polymer paint; 90 × 180 cm.